Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mnwp.160073

Follow the race to ratification…

On May 21, 1919, the US House of Representatives passed language for a constitutional amendment affirming the right to vote in the US could not be denied because of one's gender.

Adding the amendment to the US Constitution required passage by two-thirds of each chamber of Congress, then ratification by three-fourths of the states, which in 1919 was 36 of the 48 states. (Alaska and Hawai'i were still US territories.)

The House had passed it one time before in early 1918, but the Senate had not followed suit. Would it pass the amendment this time? Would 36 states ratify the amendment?

Follow the ratification process and connect to the places where the historic struggle for women's suffrage resonates.

Action by Congress

"Civilization has reached a stage, a period, a moment, when we can ring the liberty bell again and announce that this great step forward has been taken." With this powerful statement the U.S. House of Representatives once more took up debate over a proposed constitutional amendment granting women the right to vote. Keenly aware that they were part of a shrinking minority in the House, anti-suffrage representatives absolved themselves of responsibility by indicating that the power to decide would ultimately reside with the states. After three and a half hours of debate, the House once again passed the measure, this time by a vote of 304 to 90. It was now up to the Senate to act.

At long last Congress had done its part; now it was up to the states. Suffragists turned their attention to rallying 36 states to move quickly to ratify the amendment, while the opposition targeted 13 states to oppose ratification. Despite the Senate victory, the outcome for the amendment was not assured.

The First States to Ratify

"A Vote for Every Woman in 1920!" declared the National American Woman Suffrage Association after the passage of the 19th Amendment by Congress on June 4, 1919. To achieve that goal, the legislatures of 36 states would have to ratify the amendment within the next year or so. On June 10, 1919, the Wisconsin legislature voted in favor of ratification, with only two assemblymen and one senator voting against it. Although Illinois had voted for ratification earlier in the day, an administrative error meant that they had to redo the vote a week later. That made Wisconsin the first across the finish line in the race to ratification. Later in the day, Michigan lawmakers voted unanimously to ratify. Other than these three states, only Pennsylvania and Massachusetts legislatures were in session that June, but other state governors were considering calling special sessions to vote on the amendment. The race to ratification continued.

June 16, 1919 was ratification day for several states that were at the vanguard in the fight for women's suffrage. Kansas, Ohio, and New York called special sessions of their legislatures to vote in favor of the 19th Amendment.

Kansas had held the first ever referendum for women's suffrage in 1867. Although the measure was defeated, women in Kansas continued to fight for the right to vote and run for office. In 1887, the town of Argonia, Kansas became the first to elect a woman mayor. The Kansas legislature voted unanimously to ratify the amendment.

Women in Ohio had organized some of the earliest women's rights conventions in 1850 and 1851. In 1919, the Ohio assembly not only voted to ratify the federal amendment but also approved a measure granting Ohio women the right to vote in the November 1920 presidential election, in case the amendment was not in effect by then.

The ratification measure passed through both houses of the New York legislature without a dissenting vote, although one anti-suffrage senator abstained. New York had been the birthplace of the women's suffrage movement. Securing the ballot for women in New York had been a key component in Carrie Chapman Catt's Winning Plan, a goal that was reached in November 1917.

Less than two weeks after Congress sent the amendment to the states, the race to ratification was heating up.

Summer 1919 Brought More States...and the First Rejection

Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America, Radcliffe Institute

Pennsylvania women had been at the forefront of the struggle for women's rights since even before the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848. In 1915, a replica of the Liberty Bell toured all counties of Pennsylvania to campaign for passage of a referendum amending the state constitution to permit woman suffrage. The Justice Bell was set to ring on election day that year to announce victory for Pennsylvania women, but it remained silent. The referendum had been defeated. But on June 24, 1919, Pennsylvania became the seventh state to ratify the 19th Amendment, moving the nation closer to victory in the race to ratification. Perhaps the Justice Bell would have a chance to ring soon.

Massachusetts, the state which hosted the first National Woman's Rights Convention in 1850, became the eighth state to ratify the 19th Amendment on June 25, 1919. Many prominent suffragists had called Massachusetts home, including Lucy Stone and Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin. But Massachusetts women had only been successful in winning the right to vote and run for office in school committee elections. The state was also home to a powerful anti-suffrage association. As a result, attempts to expand woman suffrage in Massachusetts met with defeat. But the anti-suffragists could not keep Massachusetts from crossing the finish line in the race to ratification.

Less than a month after Congress passed the 19th Amendment, the race to ratification was already one-quarter of the way to the goal. Texas became the ninth state to ratify the amendment on June 28, 1919. Texas was also the first southern state to vote in favor of the national suffrage amendment, a significant victory since resistance to woman suffrage had been particularly strong in the south. In 1918, Texas women had won the right to vote in primary elections. The Texas legislature had also passed a resolution in January 1919 to amend the Texas state constitution allowing women to vote in all elections. When the state amendment was put to Texas voters in the May 1919 general election, it had been defeated. Texas women were unable to vote in that general election but with the state’s ratification of the 19th amendment, they and women across the country were now one step closer to full enfranchisement.

Iowa was home to many well-known suffragists, including Carrie Chapman Catt, and the town of Council Bluffs held one of the nation's first woman suffrage marches in 1908. But Iowa women were only able to win limited suffrage. They were able to vote on tax and bond issues, but not for candidates. To expand the franchise required an amendment to the Iowa state constitution which was a lengthy and difficult process. Woman suffrage proposals were introduced over and over beginning in the 1860s, but never made it through. But on July 2, 1919, Iowa crossed the finish line in the race to ratification and became the tenth state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

“Missouri must take the lead in this long-deferred justice to the state and the nation,” declared Gov. Frederick Gardner as he called a special session of the Missouri legislature to consider the issue of woman suffrage. The lawmakers responded to the governor’s call and voted to ratify the 19th Amendment on July 3, 1919. Four months earlier, in March 1919, Missouri women had won the right to vote for president. But Missouri suffragists' efforts to win full enfranchisement since 1867 had been repeatedly defeated. As the eleventh state in the race to ratification, Missourians had now done their part to ensure full suffrage for women across the country.

Anti-suffrage sentiment was strong in Georgia, but a few determined women worked hard to overcome it. Helen Augusta Howard organized the Georgia Woman Suffrage Association in 1890 with only a few members. Howard was able to convince national suffrage leaders to hold the 1895 National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) convention in Atlanta. In a concession to the segregationist South, African American women were not invited to attend the meeting. Afterwards, Susan B. Anthony and other leaders traveled around the southern states to win support for suffrage. Public opinion eventually began to shift but not quickly enough to overcome the antis in Georgia. On July 24, 1919, Georgia became the first state to reject ratification of the 19th Amendment. After the amendment was ratified by enough states in August 1920 to become part of the U.S. Constitution, Georgia women still could not vote in the November 1920 election--state lawmakers refused to waive a requirement that all voters be registered six months in advance. In 1970, Georgia voted in favor of the 19th Amendment as a formality.

Arkansas became the twelfth state to ratify the 19th Amendment on July 28, 1919. The measure passed easily through both houses of the state legislature. The news came as a relief to suffragists across the country less than a week after the defeat of ratification in Georgia. As in many states, the fight for suffrage was difficult in Arkansas. But women had won the right to vote in primary elections in Arkansas in 1918. And Arkansas would later become the first state to elect a woman to the U.S. Senate when Hattie Caraway won a special election to fill her late husband's seat in 1932.

Suffragists enjoyed two more victories in the race to ratification on August 2, 1919. First, the governor of Montana certified the legislature's July 30 vote to ratify the 19th Amendment. Then that same day, the Nebraska legislature voted unanimously to ratify. Suffragists around the country were hopeful that they were back on track for full ratification by 1920. Fourteen states won, 22 to go.

After more than a month of waiting, another state was in the "win" column when Minnesota voted to ratify the 19th Amendment on September 8, 1919. Minnesota women had first won the right to vote in school board elections in 1875. Despite growing membership across the state in many suffrage organizations, including the Minnesota Woman Suffrage Association and the Scandinavian Suffrage Association, women had been unable to win full suffrage in Minnesota. Now Minnesota had become the fifteenth state across the finish line in the race to ratification.

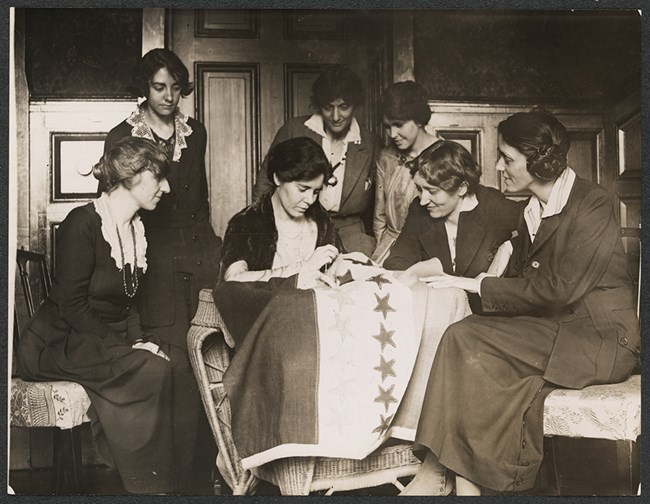

In a special session called by Governor John Bartlett, the New Hampshire legislature voted to ratify the 19th Amendment on September 10, 1919. A sixteenth star for the National Woman's Party Ratification Banner! Many New Hampshire suffragists joined the fight for the federal suffrage amendment after repeated attempts to win voting rights in their state. Sallie Hovey joined the National Woman's Party and was involved in intense lobbying efforts, which were just as important in the fight as the NWP's picketing campaign. To win the necessary 20 additional states before the November 1920 elections required more state governors to call special sessions of the legislatures. Would they make it across the finish line in the race to ratification?

Add one more state in the loss column in the race to ratification. On September 22, 1919, the Alabama legislature voted against ratifying the 19th Amendment. Although the vote was a disappointment, it was not much of a surprise. Anti-suffrage sentiments were very strong in Alabama. Women like Pattie Jacobs, president of the Alabama Equal Suffrage Association, fought hard for women's right to vote but could not make much progress.

What would Autumn 1919 bring?

Utah was a pioneer in the fight for woman suffrage. Women in the Utah territory won the vote in 1870 but lost it 1887 through a law passed by the U.S. Congress. When Utah became a state in 1896, women's right to vote was protected by the state constitution. An early supporter of a national amendment enfranchising women, Utah became the 17th state to ratify the 19th Amendment on September 30, 1919.

Another early adopter of woman suffrage was the eighteenth state in the race to ratification. California voted to ratify the 19th Amendment on November 1, 1919. Tireless effort by California women finally won the vote in 1911. Then suffragists from the Golden State turned their attention to demanding passage of the federal amendment so that women across the country could share in their victory. Thanks to California, American women were now one step closer in that fight.

Maine, like many New England states, was home to women's rights activism as early as the 1850s. Suffragists campaigned for decades to amend the state constitution to allow women to vote. Although their efforts were repeatedly defeated, women and men fighting for suffrage were able to win support in the Maine legislature--it passed a state constitutional amendment which failed when put to a statewide vote in 1917. After Congress passed the federal amendment, Maine’s governor called a special session to consider it. On November 5, 1919, Maine became the nineteenth state to ratify the 19th Amendment. Another star for the ratification banner!

The Holiday Season: The Fight Moved West

When South Dakota became a state in 1889, it looked like it was about to become the first state in the country in which women had the same right to vote as men. The new state constitution required that a woman suffrage amendment be sent to the voters. Emma Smith Devoe campaigned all around South Dakota for passage of the amendment, but it was defeated. Over the years, similar amendments were sent to South Dakota voters several times but never passed. Finally in 1918, South Dakota women won the vote. On December 4, 1919, South Dakota became the twenty-first state to ratify the 19th Amendment. Women across the country were one step closer to the same right to vote as South Dakotan women. The race to ratification continued.

(Note: after the 1890 campaign, Emma Smith Devoe moved away from South Dakota and continued to fight for woman suffrage wherever she moved.)

The final state over the finish line in 1919 in the race to ratification was Colorado. Women of Colorado had been voting on the same terms as men since 1893. Colorado was the first state to enfranchise women by referendum, meaning that the people of Colorado voted in an election to enfranchise women. Suffrage leaders often called upon Coloradan women to use the power of the ballot to elect representatives who would support the 19th Amendment so that women across the country would be able to vote as well. On December 15, 1919, Colorado became the twenty-second state to ratify the amendment. Fourteen more states would have to ratify in 1920 for women to win the vote in every state.

Ringing in the New Year with More State Ratifications

Two victories in the Race to Ratification to begin the new year! The states across the finish line on January 6, 1920 had been wrestling with women's right to vote for decades. Rhode Island, the first with a statewide suffrage organization, voted nearly unanimously to ratify the 19th Amendment. Later that afternoon, the vote in Kentucky to ratify was much closer but still decisive. Women had been voting in school elections in rural areas of Kentucky since 1838, ten years before the Seneca Falls Convention. Attempts over decades to fully enfranchise women in both states had fallen short so far. With these two ratifications, women in Rhode Island and Kentucky—and across the country—were even closer to winning the vote.

The 25th state to ratify the 19th Amendment was Oregon. Sylvia Thompson, the only woman serving in the state legislature, introduced the ratification measure in the Oregon House of Representatives on January 12, 1920. Although both the House and Senate were eager to pass it, confusion and conflict delayed the final passage until the next day. On January 14, 1920, the Oregon Secretary of State certified the ratification. The delay was in keeping with the history of woman suffrage in Oregon. Six times between 1884 and 1910, the Oregon legislature had passed an amendment to the state constitution enfranchising women only to have the measures defeated when put to the voters. Finally, in 1912 women in Oregon won the vote. With their ratification of the 19th Amendment, Oregonians gave their support to suffrage for every woman in the United States.

Hoosiers were the next across the finish line in the Race to Ratification. On January 16, 1920, Indiana ratified the 19th Amendment. Suffragists in Indiana began fighting for the right to vote beginning in the 1850s. Susan B. Anthony addressed the Indiana legislature in 1897 and implored the men to "Make the brain under the bonnet count for as much as the brain under the hat." But even a partial suffrage bill passed by the Indiana General Assembly in 1917 was struck down by the state supreme court. Many Indiana women put their hope in the federal amendment. Now thanks to Indiana, it is one step closer to victory.

The first U.S. territory and state to enfranchise women also became the 27th state in the race to ratification when Wyoming ratified the 19th Amendment on January 27, 1920. One year after Wyoming became a territory in 1868, the tiny territorial legislature passed a woman suffrage bill with 13 votes in favor, 6 against. Two years later in 1871, lawmakers unhappy with the way women were voting passed a repeal of the bill, but it was vetoed by the governor. Wyoming women held onto the right to vote and it became part of the new state's constitution in 1890.

After a string of victories, suffragists met a defeat when the South Carolina Senate, following the lead of the state House of Representatives, voted overwhelmingly to reject ratification of the 19th Amendment on January 28, 1920. Women had been fighting for the right to vote in South Carolina for decades. An attempt to amend the state constitution to include women as eligible voters failed in 1895. Niels Christensen, son of suffragist Abbie Christensen, introduced a suffrage bill during every session throughout his 40-year term as a state senator with no success. It looked like a federal amendment was the only way that women in South Carolina would ever win the vote.

What would the spring legislative season bring?

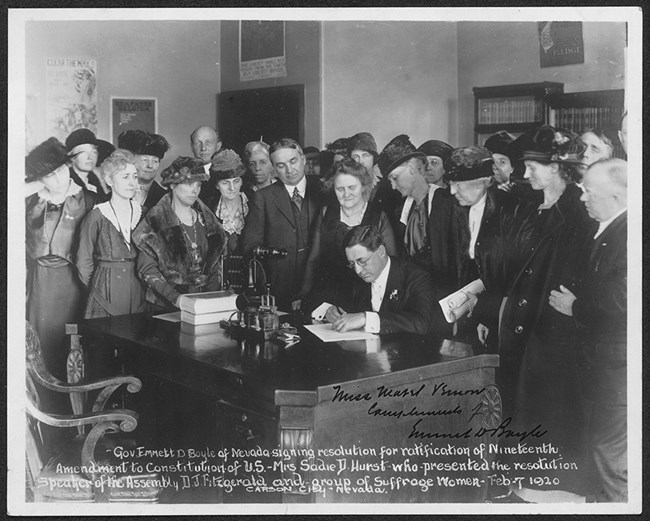

Nevada ratified the 19th Amendment on February 7, 1920. Like women in several other Western states, women in Nevada had won the right to vote in state and local races in 1914. Nevadan Anne Martin coordinated the state campaign as leader of the Nevada Equal Franchise Society. Later, she became the National Woman's Party legislative chairman. Along with other suffragists like Bird Wilson and Delphine Squires, Martin lobbied for the federal amendment so that women across the country could enjoy the same right. The Nevada legislature called a special session in February 1920 to vote on the 19th amendment. Sadie Dotson Hurst, Nevada's first female legislator, presided. The amendment passed, 25-1.

Next up to ratify the amendment was New Jersey on February 9, 1920. New Jersey had a long history of women's suffrage. The state's Revolutionary War-era constitution allowed all property-owning residents to vote, including unmarried women and people of color. But in 1807, the state passed a new law disenfranchising everyone except white men. More than a hundred years later, New Jersey women will finally get to exercise their rights again--if ratification succeeds!

Women in Idaho won the right to vote in 1896, making Idaho the fourth state to enfranchise women on the same terms as men. The National Woman's Party often campaigned in Idaho for a federal suffrage amendment so that women across the country could participate in the political process. On February 11, 1920, Idaho became the 30th state to ratify the amendment.

After several failed attempts to win the vote in the territorial legislature, Arizona suffragists finally achieved victory soon after Arizona became a state on February 14, 1912. By building coalitions among different communities, women like Frances Willard Munds were able to bypass the new state government and take the issue of woman suffrage right to the voters. Arizona became the tenth state in which women could vote on the same terms as men when the woman suffrage initiative on the ballot in November 1912 passed overwhelmingly. Support for woman suffrage grew during the seven years of Arizona's inclusion of women as fully enfranchised citizens. The vote in the legislature was unanimous to ratify the federal amendment. Arizona became the thirty-first state to ratify it on February 12, 1920. Only five more states to go in the Race to Ratification.

February 12, 1920, brought both a win and a loss for the amendment. On the same day that Arizona ratified it, the Virginia legislature voted to reject. The vote was not a surprise. When Virginia suffragists tried to convince the state legislature to take up ratification of the suffrage amendment during a special session in August 1919, the idea was met with scorn. Instead, lawmakers passed a resolution declaring the amendment "unwarranted, unnecessary, undemocratic and dangerous interference with the rights reserved to the States..." Appeals by Virginia's pro-suffrage governor and President Wilson were unsuccessful. Virginia did symbolically ratify the amendment 32 years later on February 21, 1952.

When New Mexico became a state in 1912, women won the right to vote in school elections. But the state constitution made it so difficult to expand the franchise that New Mexico suffragists concentrated on support for a federal woman suffrage amendment. Nina Otero-Warren, head of the National Woman's Party New Mexico chapter, was instrumental in winning support from Spanish-speaking New Mexicans. The Ratification Banner gained another star on February 21, 1920, when New Mexico ratified the amendment. Only four more states needed until the Race to Ratification is complete.

The Race to Ratification suffered another defeat when, on February 24, 1920, Maryland became the fifth state to reject ratification of the amendment. Maryland suffragists felt that they were "railroaded" by leadership in the legislature. They believed that they were deliberately given wrong information about when hearings on the amendment would be held. No speakers were available to advocate for ratification, but the anti-suffragists were ready, and their argument won the day. By the time the General Assembly had voted against the amendment, Maryland suffragists had gathered at the State House and "with colors flying and playing martial airs marched two by two around the capitol." They put their hope in other states to bring suffrage to Maryland through ratification of the amendment. Maryland symbolically ratified the amendment on March 29, 1941.

(Quote from the Maryland Suffrage News published by the Maryland Just Government League.)

Oklahoma ratifies the 19th Amendment on February 28, 1920! The Woman's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) started to push for suffrage in Oklahoma Territory and Indian Territory in the 1890s. NAWSA soon joined them. Suffragists like Narcissa Chisholm Owen, a part-Cherokee leader based in Muskogee, worked in the Woman Suffrage Association of Oklahoma and Indian Territory. Suffrage was a large part of battles over Oklahoma statehood. Advocates lobbied hard for women's enfranchisement to be included in any new state constitution. While this tactic had worked in other Western states like Wyoming, it failed in Oklahoma. But suffragists like Adelia C. Stephens and Kate Stafford did not give up. In 1918 the state amended its constitution to permit suffrage. Two years later it ratified the 19th Amendment--bringing it one step closer to becoming law.

A dramatic day in West Virginia wins the 34th state for suffrage! The amendment had passed the West Virginia House during its special session. But the Senate deadlocked, 14-14. Both sides rushed to call in reinforcements. Anti-suffrage Senator A. R. Montgomery traveled from his new home in Illinois. He prepared to take his seat and vote "no." Meanwhile, frantic suffragists telegraphed to their supporter Senator Jesse A. Bloch, who was vacationing in California. They begged him to rush home as soon as possible. Bloch, who had been taking a leisurely swim when he received the message, didn't even change out of his bathing suit. He packed his golf clubs, hopped an express train, and began a "sensational cross-country flying trip" to Charleston. The Republican National Committee offered to pay for a plane to take him part of the way, but his wife--though a loyal suffragist--objected to the "perils" of air travel. But West Virginia suffragists, led by Lenna Lowe Yost, bought Bloch some time. They argued that, since anti-suffrage Senator Montgomery had moved out of state, he was no longer eligible to hold his seat and should not be allowed to vote. Amid an uproar, their maneuver succeeded. The House adjourned until the following day. Around 2:30 in the morning, Bloch's train pulled into the station. He entered the Senate chamber a few hours later. Supporters greeted him with cheers and applause. Bloch fastened a yellow rose--the symbol of suffrage--into his buttonhole. After the final roll call for ratification, suffragists erupted into celebration. They filled the hallways, cheering and blowing on the tin horns that they had kept hidden during the session. With only two more states to go, it seemed like ratification would be complete by the end of March 1920.

Washington becomes the 35th state to ratify the 19th Amendment on March 22, 1920. Washington women had long been politically active. Advocates like Emma Smith DeVoe had worked to win statewide suffrage ten years before. In 1913, Frances Axtel and Nena Jolidon Croake were sworn in as Washington's first female legislators. Meanwhile, Washington suffragists focused on winning the 19th Amendment. Ratification there set off a final sprint to find the 36th state.

The Hunt for the 36th State Begins

Mississippi gets all tangled up near the finish line in the Race To Ratification. While it briefly looked like the Magnolia State had a chance to become the 36th and final state to ratify the 19th Amendment, the effort ultimately went down in defeat on March 31, 1920. The Mississippi legislature originally rejected ratification of the woman suffrage amendment in February 1920. However, fears arose that Delaware, a "Republican state" would get the credit for a Votes for Women victory. That could hurt the Democratic party in the upcoming presidential election. In an attempt to thwart the narrative of Republicans as champions of democracy, the Mississippi senate reversed course and reconsidered the amendment. The vote was a tie. The state Lieutenant Governor broke the tie in favor of ratification on March 30, 1920. The state house of representatives, unconvinced by the senate strategy, voted against ratification again the next day. The hunt for the 36th state continued! Mississippi would not officially ratify the 19th Amendment until 1984.

It was a shocking defeat out of the Mid-Atlantic as Delaware rejected the suffrage amendment, keeping it one state away from ratification. No state had ratified since Washington on March 22. But NAWSA leaders, including Carrie Chapman Catt, had felt confident that their victory would arrive in Delaware. Though the state had long been divided on the suffrage question, suffragists like Fannie Hopkins Hamilton and Mabel Vernon had been working for years to win women in the vote. Anti-suffragist leaders mounted a strong lobbying campaign to stop them. Their allies intensely lobbied Delaware lawmakers, threatening them with the loss of their seats if they voted for suffrage. The tactics worked. The Delaware legislature voted down the suffrage amendment on June 2. Momentum seemed to shift against the suffragists in a dangerous way. Both sides understood that the rest of the map would be difficult. Most of the states yet to vote were hostile to the cause. Tennessee seemed like suffragists' only chance.

In June 1920, the Louisiana state House and Senate voted against ratifying the federal amendment. However, the state House of Representatives passed an amendment to the state constitution to include women as eligible voters on June 2. Two weeks later, on June 17, 1920, the state Senate voted down the state amendment. The cause of woman suffrage in Louisiana was defeated twice in one month.

But 1920 was an election year, and the presidential candidates were now vying for the support of women who had won the right to vote in their states. That summer, Republican Warren G. Harding and Democrat James M. Cox each hoped to claim credit for their party in the suffrage victory before November. Despite pleas by Democratic nominee Cox for Louisiana to reconsider so that a Democratic state could be the 36th state to ratify, on July 9, 1920, the Louisiana legislature adjourned without ratification of the 19th Amendment.

Tennessee

Library of Congress "Chronicling America" digital collection

After a long series of victories, the defeats in Delaware and Louisiana brought final ratification perilously close to failure. Tennessee was meeting in special session to consider the amendment and Suffs and Antis marshalled their forces at the capitol in Nashville, staying at the nearby Hermitage Hotel...yellow roses worn by the Suffs, red for the Antis. The Senate had voted to ratify, so it was up to the House. The vote was on August 18, and it looked like there were enough red roses on the House floor for the amendment to go down. One member wearing a red rose in his lapel, Harry Burn, thought of the letter in his pocket from his mother, Pheobe (nicknamed “Febb”), who had written, “Dear Son... Hurray and vote for suffrage and don’t keep them in doubt... Don’t forget to be a good boy...” Harry cast the tie-breaking vote for the amendment. With this, Tennessee became the 36th state and the amendment had passed the threshold for ratification by three-fourths of the states. It was on its way to Washington to be certified as the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

But Antis weren’t done. A challenge to Tennessee’s ratification was in the works. Would it be successful? Would all of this effort be overturned?

Certification: The 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

After the Tennessee House vote on August 18, Speaker Seth Walker immediately called for reconsideration of ratification of the amendment. Although anti-suffrage legislators in Tennessee tried desperately to discredit Harry Burn and others, their efforts failed. No one was willing to change their vote. The House adjourned on August 20, 1920, without reconsidering the ratification of the amendment. "I want to state that I changed my vote in favor of ratification first because I believe in full suffrage as a right," Harry Burn emotionally addressed the chamber. "I believe we had a moral and legal right to ratify; and I knew that a mother's advice is always safest for a boy to follow, and my mother wanted me to vote for ratification."

At long last, the Race To Ratification was won. Suffragists rushed from Nashville to Washington, D.C. to witness the event and hired photographers with movie cameras to capture the historic moment. But Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the proclamation to certify the 19th Amendment in his house early in the morning of August 26, 1920. So we have no pictures of the moment that American women became fully enfranchised citizens in the U.S. Constitution.

Collections of the Library of Congress https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2020635501/

Looking Beyond the 19th Amendment

Women headed to the polls in the November 1920 election, although it would be decades before eligible women voted at the same rate as their male counterparts.

And for more than a year, it was unclear whether the ratification victory would hold. A Maryland judge named Oscar Leser filed a lawsuit claiming that the character of the 19th Amendment excluded it from being added to the Constitution. In a unanimous decision in Leser v. Garnett, the Supreme Court confirmed the amendment's constitutionality on February 22, 1922. The right of citizens of the United States to vote could not be denied based on sex.

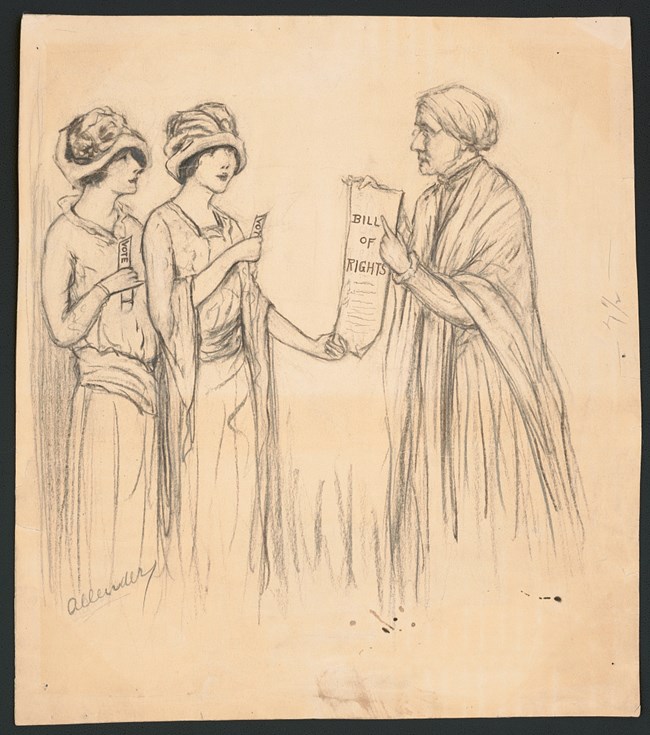

But the 19th Amendment was only "the first lap of this struggle for women's emancipation" according to Carrie Chapman Catt. Alice Paul declared, “It is incredible to me that any woman should consider the fight for full equality won. It is just beginning." Women got to work. Across the country, they ran for office in local, state, and national elections. They used the organizational skills they had developed fighting for the vote to campaign for equal treatment under the law, like the right to serve on juries and to receive equal pay for equal work.

But white women activists continued to marginalize women of color in the leadership of their organizations and in the issues they championed. African American women faced the same discrimination, oppression and violence as men when they tried to vote. Black women remained on the forefront in the Black Freedom struggle, fighting for voting rights and an end to lynching. They were instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Native American suffragists worked for US citizenship for tribal members, a fight they won in 1924 with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act.

But the ballot is just the beginning of the work. The fight for justice continues. The Race to Ratification was the first leg in the marathon relay towards equality. Each generation hands the baton to the next. For more than a century since winning the vote, women have raised their voices and worked to create a more perfect union.

What will the next 100 years bring?

Find a park to learn more about women's history

Find a park or place and events in parks across the country.