Last updated: June 27, 2019

Person

Susan B. Anthony

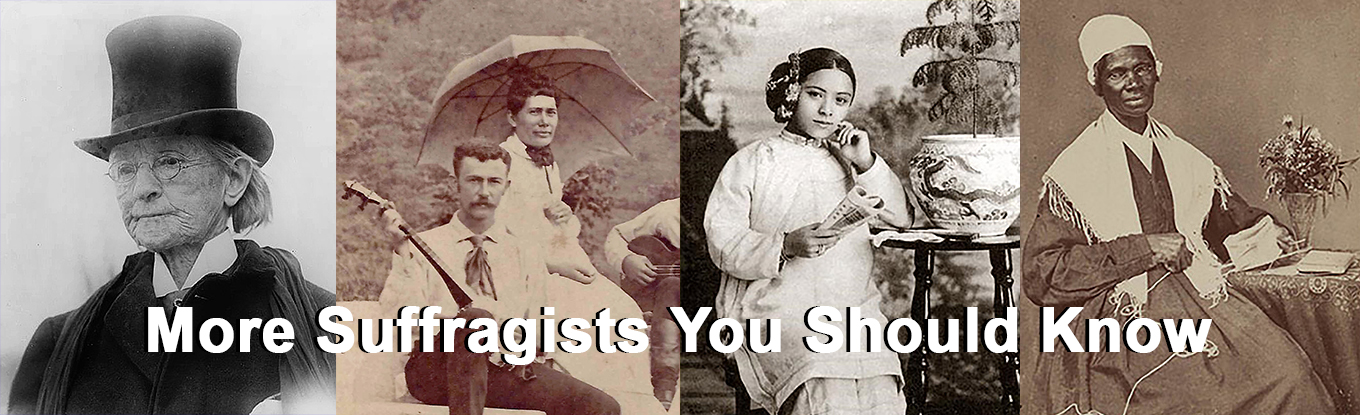

From "The History of Woman Suffrage" by Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Volume 1, 1881.

Susan B. Anthony is perhaps the most widely known suffragist of her generation and has become an icon of the woman’s suffrage movement. Anthony traveled the country to give speeches, circulate petitions, and organize local women’s rights organizations.

Anthony was born in Adams, Massachusetts.[1] After the Anthony family moved to Rochester, New York in 1845, they became active in the antislavery movement. Antislavery Quakers met at their farm almost every Sunday, where they were sometimes joined by Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. Two of Anthony's brothers, Daniel and Merritt, were later anti-slavery activists in the Kansas territory.

In 1848 Susan B. Anthony was working as a teacher in Canajoharie, New York and became involved with the teacher’s union when she discovered that male teachers had a monthly salary of $10.00, while the female teachers earned $2.50 a month. Her parents and sister Marry attended the 1848 Rochester Woman’s Rights Convention held August 2.

Anthony’s experience with the teacher’s union, temperance, and antislavery reforms, and her Quaker upbringing, laid fertile ground for a career in women’s rights reform to grow. The career would begin with an introduction to Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

On a street corner in Seneca Falls in 1851, Amelia Bloomer introduced Susan B. Anthony to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and later Stanton recalled the moment:

Meeting Elizabeth Cady Stanton was probably the beginning of her interest in women’s rights, but it is Lucy Stone’s speech at the 1852 Syracuse Convention that is credited for convincing Anthony to join the women’s rights movement.“There she stood with her good earnest face and genial smile, dressed in gray silk, hat and all the same color, relieved with pale blue ribbons, the perfection of neatness and sobriety. I liked her thoroughly, and why I did not at once invite her home with me to dinner, I do not know.”

In 1853 Anthony campaigned for women's property rights in New York State, speaking at meetings, collecting signatures for petitions, and lobbying the state legislature. Anthony circulated petitions for married women's property rights and woman suffrage. She addressed the National Women’s Rights Convention in 1854 and urged more petition campaigns. In 1854 she wrote to Matilda Joslyn Gage that “I know slavery is the all-absorbing question of the day, still we must push forward this great central question, which underlies all others.”

By 1856 Anthony had become an agent for the American Anti-Slavery Society, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters, and distributing leaflets. She encountered hostile mobs, armed threats, and things thrown at her. She was hung in effigy, and in Syracuse, New York her image was dragged through the streets.

At the 1856 National Women’s Rights Convention, Anthony served on the business committee and spoke on the necessity of the dissemination of printed matter on women’s rights. She named The Lily and The Woman’s Advocate, and said they had some documents for sale on the platform.

Anthony and Stanton founded the American Equal Rights Association (AERA) and in 1868 became editors of its newspaper, The Revolution. The masthead of the newspaper proudly displayed their motto, “Men, their rights, and nothing more; women, their rights, and nothing less.” Also that year, the Fourteenth Amendment passed, recognizing that those born into slavery were entitled to the same citizenship status and protections as free people. The amendment did not, however, grant universal access to the vote.

A rift appeared among those, like Stanton and Anthony and Frederick Douglass, who had been allies in the fight for universal suffrage. Anthony and Stanton were hurt that Douglass supported the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted the vote to Black men only. They felt he had abandoned woman suffrage. Douglass, in turn, was hurt by the insulting arguments of Anthony and Stanton against African Americans. They all thought that it would be impossible to get the vote for both women and African Americans at the same time, and disagreed with the others’ priorities. The rift turned ugly at a public meeting of the AERA held in New York City in 1869.Following the meeting, Stanton, Anthony and others formed the National Woman Suffrage Association and focused solely on a federal woman’s suffrage amendment. In an effort to challenge suffrage, Anthony and her three sisters voted in the 1872 Presidential election. She was arrested at her

Rochester, New York home and put on trial in the Ontario County Courthouse, Canandaigua, New York.[2] The judge instructed the jury to find her guilty without any deliberations, and imposed a $100 fine. When Anthony refused to pay a $100 fine and court costs, the judge did not sentence her to prison time, which ended her chance of an appeal. An appeal would have allowed the suffrage movement to take the question of women’s voting rights to the Supreme Court, but it was not to be.From 1881 to 1885, Anthony joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton and

Matilda Joslyn Gage in writing the History of Woman Suffrage. This extensive work focuses solely on white women suffragists, and does not include any suffragists of color.In 1890, the National Woman Suffrage Association merged with the American Woman Suffrage Association, which argued for state-by-state enfranchisement of women (among other differences). Elizabeth Cady Stanton was the first president of the new group, the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), but Anthony was effectively its leader. Anthony became NAWSA president in 1892.

Carrie Chapman Catt replaced Anthony as president of the organization when she retired in 1900.Susan B. Anthony also worked for other causes, including playing a key role in the creation of the International Council of Women and helping to organize the World’s Congress of Representative Women at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. She remained active until the end of her life. In 1893, Anthony started the Rochester branch of the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union. She also worked to raise money that the University of Rochester required before they would agree to admit women as students. In 1895, Anthony toured

Yosemite National Park by mule.Susan B. Anthony died on March 13, 1906 of heart failure and pneumonia at her Rochester home. She was buried at Mount Hope Cemetery, also in Rochester.[3]

As a final tribute to Susan B. Anthony, the

Nineteenth Amendment was named the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. It was ratified in 1920. Susan B. Anthony is also the first non-fictional woman to be depicted on US currency: from 1979 to 1981 and again in 1999, her portrait was on the United States dollar coin.

Notes:

[1] The Susan B. Anthony Birthplace at 67 East Road, Adams, Massachusetts, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 3, 1865. It is operated as an historic house museum.

[2] The Susan B. Anthony House, 17 Madison Street, Rochester, New York was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 23, 1965. The Ontario County Courthouse, Canandaigua, New York, is a contributing property of the Canandaigua Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 26, 1984 (boundary increase June 7, 2016).

[3] The Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 30, 2018.