Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

The American Home Front During World War II: Incarceration and Martial Law

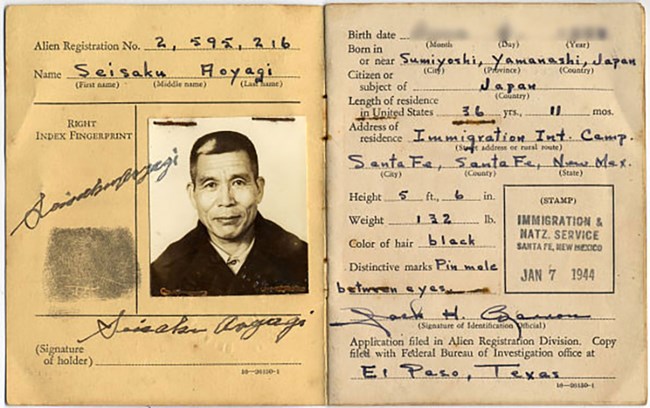

Collection of Smithsonian National Museum of American History (2015.0252).

Enemy Alien Detention Camps

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the President issued Executive Orders 2525, 2526, and 2527. These declared all foreign nationals of Japan, Italy, and Germany (respectively) as enemy aliens. Several thousand were immediately arrested, having been previously identified by the FBI as allegedly dangerous to the United States. [3] Hundreds of thousands of others were placed under mandatory restrictions. These included: registration as an enemy alien; a requirement to carry registration papers with them at all times; forced relocation; travel restrictions; and a curfew. These restrictions forced many to move out of their homes, particularly along the coasts. They also limited how and why people could travel from home without applying for special permission. Several people designated enemy aliens had property seized, including their means of livelihood like fishing boats. Enemy aliens were also forbidden from owning cameras, weapons, flashlights, and short-wave radios. [4]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2015634494/).

Japanese War Relocation Authority Incarceration Centers

In February 1942, the President issued Executive Order 9066. It established “military areas” across California and in parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona. People – including American citizens – could legally be excluded from these places. The government used the Executive Order to justify the forced expulsion of people of Japanese descent from the exclusion zone. A few thousand Japanese and Japanese Americans left before the government could incarcerate them. [6] A total of about 120,000 people with as little as 1/16 Japanese ancestry (i.e. a single great grandparent) were forced into War Relocation Authority centers. Approximately 70,000 of these people were American citizens. There were no charges against any of them, and no system (besides the courts) for them to appeal their removal or the seizure of their property.[7]

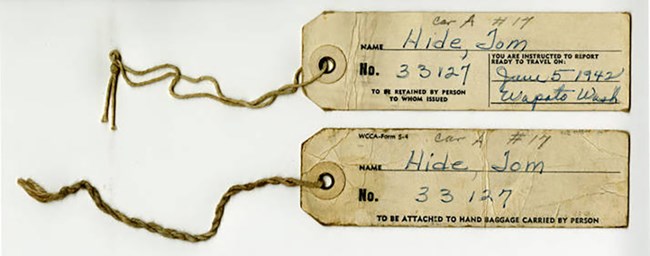

Collection of Washington State Universities Libraries: Manuscripts, Archives, and Special Collections, Tom Hide Collection (SC 014.1).

The first stop was at a Control Center, where the government issued families a number and told them when and where to report. Families became known only by their numbers. At the allocated time, families -- wearing their number tags -- boarded buses or trains that took them to assembly centers. These were set up in places like fair grounds and race tracks surrounded by barbed wire, searchlights, and guard towers. Living quarters were cramped and rough. Some people lived in hastily-converted horse stalls; others in stockyard buildings. People spent an average of 100 days in an assembly center before being transferred to one of the War Relocation Centers. [9]

Collection of National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 537019).

The last American incarceration center for people of Japanese descent closed in 1948. [11] In 1982, the US government found that the incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans stemmed from “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” [12]

Forced Relocation of Alaska Natives

Following the Japanese invasion of Alaska’s Aleutian Islands, over 800 Native Alaskans were forcibly relocated, "for their own safety." Allowed to bring only a few items like one bag and one blanket each, the US military shipped them thousands of miles from their homes. They were held in terrible conditions in Southern Alaska until the end of the war in 1945. Almost 120 Unangax̂ perished in the US camps; about half of those sent to Japan as prisoners also died. The US government forbade many of the survivors from returning to their homes. [13]

Collection of the National Park Service.

Prisoner of War Camps

The United States was host to more than 425,000 Prisoners of War. These were mostly Germans, but tens of thousands of Italians and thousands of Japanese POWs were also interned here. [14] After capture overseas, the military shipped POWs to the US, where they were imprisoned in one of over 700 camps.[15] Unlike those held as enemy aliens or sent to the WRA centers, the treatment of POWs was dictated by the Geneva Convention. They were fed well, given clothing and toiletries, and had access to the same medical and dental treatment as US troops. [16] Many Americans felt that the POWs were being treated too well, while American citizens were dying overseas. Archaeological studies at POW camp sites in the US document the experiences of those held there. [17]The government leased out as many as 265,000 POWs to fill non-military labor shortages. Many POWs worked in agriculture, picking produce, packing meat, and canning product. Farmers paid the government 45 cents per hour per POW (about $8 in 2023). The prisoners earned 80 cents per day (about $14 in 2023) for their labor, paid in camp scrip or chits. This system prevented them from having American cash if they escaped. POWs were able to spend their wages in camp canteens, with access to goods including candy, tobacco, and low-alcohol beer and wine. [18]

In September 1943, Italy surrendered to the Allies and declared war on Germany. This released Italian POWs from the Geneva Convention, allowing them to do military work.[19] This released Italian POWs from the Geneva Convention, and allowed them to take on military work. [19] Offered the chance to move to lower-security camps and work towards defeating Germany, many Italian POWs volunteered. They made up over 200 Italian Service Units (ISU) in coastal and industrial areas across the country. [20] Though paid the same as other POWs, ISU members got some of their wages in American dollars and had more freedom. Those who chose not to join the ISU program remained interned as POWs until the end of the war. [21]

Collection of the US Air Force (080112-F-2034C-203.JPG).

Americans Incarcerated by Enemy Forces

When Japan captured American territories, they generally sent US military members to POW camps in Japan, China, and elsewhere. Civilians, however, found themselves under often brutal control by the Japanese. In Manila, The Philippines, the Japanese turned the University of Santo Tomas into the Santo Tomas Internment Camp (also called the Manila Internment Camp). [22] At Wake Island, they forced 98 civilian American contractors to rebuild the island’s airstrip. Afterwards, they blindfolded and killed the Americans and buried them in a mass grave. An escapee (later caught and beheaded) chiseled the date of the massacre in a nearby rock. [23]On Guam, civilians suffered starvation, rape, murder, and forced labor under Japanese occupation. Near the end of the war, the Japanese forced up to 15,000 Chamorro to march to incarceration camps like Manenggon in the island interior. There, those who survived lived with inadequate shelter, no sanitary facilities, no medical care, and very little food until American forces freed them in July 1944. [24]

Wikimedia, Public Domain.

Conscientious Objectors

The Selective Service Act of 1940 contained provisions for conscientious objectors. The military assigned those opposed to combat to noncombatant military roles. Those who were opposed to military service at all were “assigned to [unpaid] work of national importance under civilian direction.” [25] More than 70,000 draftees claimed conscientious objector status; not all their claims were granted. Approximately 25,000 served in non-combat military duty. Another 12,000 went to Civilian Public Service (CPS) camps working in agriculture, building roads, and staffing mental hospitals. Some in the CPS served as “human guinea pigs” in a series of medical experiments done by the Office of Scientific Research & Development and the Office of the Surgeon General. These experiments included documenting the effects of starvation, cold weather, high altitude, and malaria. CPS workers logged over 8 million personnel days of work during the program. [26]There were over 150 Civilian Public Service camps across the United States, including Puerto Rico. Several of them took over former CCC camps. The first, Patapsco Camp in Maryland, opened on May 15, 1941. Over 6,000 men who refused to work at all as conscientious objectors went to prison for violating the Selective Service Act. The CPS camps were closed in March 1947. [27]

Martial Law in Hawai’i

Within hours of the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Governor of the Territory of Hawai’i declared martial law. This suspended the constitutional rights of everyone in Hawai’i, putting all legal authority in the hands of the US Army. [28]The army censored the press, long distance telephone calls and cables, and all civilian mail. They instituted a curfew and blackout, and required the registration and fingerprinting of all civilians (except small children). Many residents of Japanese descent lost their jobs. The military replaced the civil court system, trying all crimes in military courts. They wouldn't allow jury trials, believing that jurors in Hawai’i could not be impartial. Ninety-nine percent of the estimated 55,000 civilian cases heard in the military courts resulted in guilty verdicts. [29]

In a ruling towards the end of the war, the Supreme Court described the treatment of Hawaiian civilians as “a wholesale and wanton violation of constitutional liberties.” [30] The military reinstated some functions of the civilian government in March 1943, but martial law remained in effect until October 1944. [31]

It was not just those incarcerated or who were affected by enemy attacks on the home front who felt the effects of the war. Across the Greater United States, Americans found many items in short supply and were asked to recycle and to grow their own food.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] Bryant 2019; Fort McCoy Public Affairs Office 2021; Sturkol 2023.

[3] Hinnershitz 2021b; National Archives and Records Administration 2021. It is worth noting that because of existing laws, it was not possible for Issei or first generation Japanese immigrants to the United States to apply to become citizens (National Park Service 2023).

[4] The Enemy Alien Act did not apply to US citizens, but Italian Americans – particularly along the West Coast – were also targeted (Hinnershitz 2021b; Taylor 2017; Texas Historical Commission n.d.). The government knew who was under restriction because in 1940, FDR had signed the Alien Registration Act into law. Among other things, it required all foreign-born US residents to register with the government (Gage 2022).

[5] National Archives and Records Administration 2021; Texas Historical Commission n.d. Many family members of those declared enemy aliens chose to accompany their loved ones to the incarceration camps. Detainees from Latin America included a handful of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany. Not all incarcerated Germans were from Germany. The US government considered people from countries annexed or occupied by Germany as “German.” This included those from Austria, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania, and Bulgaria (Ernst 2011; Farelly 2019; German American Internee Coalition 2023; Hoh 2018; Rosenfeld 2015). For information on archaeology conducted at enemy alien detention camps, see (for example) Asian American Comparative Collection n.d.; Farrell 2017; Ross 2021: 605-606; and Camp 2012, 2019). Enemy alien detention camps across the US include:

- Camp Angel Island, San Francisco, California. Also known as Fort McDowell. Enemy aliens and POWs were held here. The US Immigration Station on Angel Island was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 14, 1971, and designated a National Historic Landmark Historic District on December 9, 1997.

- Camp Ruston, Grambling State University West Campus, Ruston, Louisiana. After its use as an Enemy Alien Internment Camp, Camp Ruston was one of the largest POW camps in the US. The Ruston POW Camp Buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 13, 1991.

- Crystal City Alien Enemy Detention Facility, Crystal City, Texas. This location held people and families from the US identified as enemy aliens, as well as many of those deported from Latin American countries for incarceration in the US. Also known as the Crystal City Internment Camp and the US Family Internment Camp, Crystal City, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 1, 2014.

- Ellis Island Detention Station, Jersey City, New Jersey and New York City. Ellis Island was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. It was included as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument, an NPS unit, on May 11, 1965. Ellis Island has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort Bliss, El Paso, Texas. Fort Bliss Main Post Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 7, 1998. Several structures at Fort Bliss have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey. These include those associated with the Post Hospital; and several individual buildings associated with the William Beaumont General Hospital complex (one of the POW hospitals across the US). The remains of several enemy aliens and POWs who died at the Lordsburg Internment Camp in Lordsburg, New Mexico were moved to the Fort Bliss National Cemetery. The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 2016. The Fort Bliss National Cemetery has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey.

- Fort McCoy, near Tomah, Wisconsin. POWs were held here, as well as enemy aliens. Fort McCoy – including the hospital where incarcerated POWs and enemy aliens were treated – has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort Missoula Internment Camp, near Missoula, Montana. In addition to those arrested as enemy aliens, Fort Missoula Internment Camp also housed Italian merchant marines and World’s Fair laborers who were in the US when it entered World War II. The crew of an Italian luxury liner seized in the Panama Canal were also incarcerated here. The Fort Missoula Historic District, including the remains of enemy alien detention buildings, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 29, 1987 (boundary increase: February 28, 2012). The Powder Magazine, Laundry Building, and the Non-Commissioned Officer Living Quarters at the Fort have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas. In addition to POWs, Fort Sam Houston was a site of incarceration of enemy aliens. Housed first in the “Old Infantry Long Barracks” (documented as the Company Barracks by the Historic American Buildings Survey), they were later moved to a compound at Dodd Field, the Fort’s airfield (Texas Historical Commission 2023). Fort Sam Houston was designated a National Historic Landmark District on May 15, 1975. The hangar at Dodd Field was documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Fort Sill, Lawton, Oklahoma. Fort Sill was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960.

- Fort Stanton, near Lincoln, New Mexico. Individuals identified as German and Japanese enemy aliens were incarcerated here, as well as hundreds of German nationals rescued by an American vessel in 1939. The crew of the luxury liner Columbus scuttled her instead of being destroyed or taken prisoner by a nearby British warship. Fort Stanton was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 13, 1973 (boundary increase: January 14, 2000). Fort Stanton, including several individual buildings have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California. Camp Griffith Park, a CCC camp located in what is now Griffith Park, served as a detention camp for several Japanese individuals suspected of being enemy aliens. It also served as a POW camp. The Griffith Park Zoo has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey.

- Grove Park Inn, Asheville, North Carolina. The Grove Park Inn served as a US State Department enemy alien diplomatic detention center. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 3, 1973.

- Honouliuli Internment Camp, Oahu, Hawai’i. Also known as the Central Pacific Camp (Frank and Seelye 2019: 61), it held POWs and enemy aliens. The Honouliuli Internment Camp was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 21, 2012. It was designated a National Monument on February 24, 2015, becoming part of the NPS. On February 19, 2015 it was redesignated Honouliuli National Historic Site.

- Santa Fe Passenger Depot, Clovis, New Mexico. After the attack on Pearl Harbor, Border Patrol officers detained the entire Japanese population of Clovis, incarcerating them at the Old Raton Ranch Internment Camp. Many had worked for the Santa Fe Railroad, many living in company-owned housing (Niiya 2021b). The Santa Fe Passenger Depot was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 14, 1995.

- The Greenbriar, White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia. The Greenbriar hotel was one of the US State Department enemy alien diplomatic detention centers. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 9, 1974 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 21, 1990.

- The Homestead, Hot Springs, Virginia. The Homestead was one of the US State Department enemy alien diplomatic detention centers. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 3, 1984 and designated a National Historic Landmark on July 17, 1991.

[6] Niiya 2020.

[7] Imai 2020; Niiya 2021a; National Archives and Records Administration 2022; Robinson 2020. Several incarcerated people of Japanese descent challenged their forced evacuation and incarceration in court. In 1944, the US Supreme Court (Korematsu v. United States) determined that forcibly removing people from the exclusion zone was legal. At the same time, in a separate case (Ex parte Endo), the Supreme Court ruled that loyal citizens could not be detained. This led to the government lifting the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. The War Relocation Authority also announced that their incarceration centers would be shut down over the course of 1945. This announcement excluded the center at Tule Lake, where “troublemakers” from the WRA centers were segregated.

[8] Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians 1982: 136; National Archives and Records Administration 2022; Vernon E. Jordan Law Library 2023.

[9] Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians 1982: 135-140. Owens Valley Reception Center, California was later incorporated into Manzanar War Relocation Center. The Parker Dam Reception Center in Arizona was later incorporated into the Poston War Relocation Center. The Parker Dam has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record. The Santa Anita Assembly Center, California was located in Santa Anita Park, which was determined eligible for listing on the National Record of Historic Places on August 3, 2006. Visible to those incarcerated at Tanforan Assembly Center in San Bruno, California was the South San Francisco Hillside Sign promoting San Francisco as an industrial city. The sign was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 11, 1996.

[10] Densho 2023; Hinnershitz 2021a, 2022b; Ross 2021: 601-602, 604-610; Shew 2010; Swader 2015. Granada War Relocation Center in Colorado was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 18, 1994, designated a National Historic Landmark on March 18, 2022, and became a National Park Unit as Amache National Historic Site on February 10, 2006. Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 19, 1985 and designated a National Historic Landmark on September 20, 2006. The Jerome Relocation Center has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey. Manzanar War Relocation Center in California was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 30, 1976, designated a National Historic Landmark on February 4, 1985, and became a National Park Unit as Manzanar National Historic Site on March 3, 1992. Minidoka War Relocation Center was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 10, 1979 and became a National Park Unit as Minidoka National Monument on January 17, 2001 and as Minidoka National Historic Site on May 8, 2008. The Poston Elementary School, Unit 1 at the Poston Relocation Center was designated a National Historic Landmark on October 16, 2012. Rohwer War Relocation Center in Arkansas was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 30, 1974. The Rohwer Relocation Center Cemetery was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 6, 1992. The Topaz War Relocation Center (also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center) in Utah was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 2, 1974 and designated a National Historic Landmark on March 29, 2007. Tule Lake War Relocation Center (later Tule Lake Segregation Center) in California was designated a National Historic Landmark on February 17, 2006; it became a National Park Unit as Tule Lake National Monument on March 12, 2019.

[11] Densho 2023.

[12] Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians 1982: 18.

[13] Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians 1982: 318, 330, 336, 337; National Park Service 2021a, 2021b; Hinnershitz 2022a.

[14] Most Japanese POWs captured by American forces were sent to Australia or New Zealand for internment. Those held in the US were believed to be of high value for intelligence purposes (Krammer 1983: 70). Places across the US associated with Axis POW incarceration include:

- Arizona Army National Guard Arsenal, Phoenix, Arizona. Located next to Papago Park, it served as the headquarters for all POW activities in Arizona during World War II. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 31, 2010.

- Benicia Army Cemetery, Benicia, California. Five German POWs died while being held at Camp Stockton, part of the Rough and Ready Naval Supply Depot on the San Joaquin River, Stockton, California. They were buried in the Benicia Army Cemetery at the Benicia Arsenal, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 7, 1976.

- Camp Angel Island, San Francisco, California. Also known as Fort McDowell. POWs and enemy aliens were held here. Located at the US Immigration Station on Angel Island, it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 14, 1971, and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 9, 1997.

- Camp Bayfield, Bayfield, Wisconsin. This POW camp was housed in the Old Bayfield County Courthouse, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 27. 1974. It is currently the headquarters of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, part of the NPS.

- Camp Breckinridge, Morganfield, Kentucky. POWs here painted murals in the Non-Commissioned Officers’ Club. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 14, 2001.

- Camp Butler National Cemetery, near Springfield, Illinois. POWs from several camps were reinterred here from POW camp cemeteries at Camp Atterbury near Edinburgh, Indiana; Camp Grant, Illinois; Camp McCoy, Wisconsin; and Fort Robinson, Nebraska. The cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 15, 1997.

- Camp Chaffee, near Fort Smith, Arkansas. The camp was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 23, 2011 (boundary increase April 6, 2014).

- Camp Clinton, Clinton, Mississippi. POWs housed at Camp Clinton worked on building the Mississippi River Basin Model, a working model of the Mississippi River. The Mississippi River Basin Model Waterways Experiment Station has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Camp Dermott, Arkansas. Following the closure of the Jerome Relocation Center, part of the former WRA camp was used as a POW camp. Camp Dermott has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey.

- Camp Glenn, Indianapolis, Indiana. Located within Fort Benjamin Harrison, Camp Edwin F. Glenn was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 1, 1995. The Fort Benjamin Harrison Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 6, 1995 (boundary increase December 1, 1995).

- Camp Hale, near Red Cliff, Colorado. Housing some of the most pro-Nazi German POWs, this camp was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 10, 1992.

- Camp Jerome, near Jerome, Arkansas. This POW camp opened on the site of the closed Jerome War Relocation Center in 1944. The Jerome Relocation Center has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Camp McCain, Grenada County, Mississippi. This POW camp was constructed on part of Glenwild Plantation. The Plantation Manager’s House was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 12, 1999.

- Camp New Ulm, near New Ulm, Minnesota. A former CCC camp, these buildings are part of the Flandrau State Park CCC/WPA/Rustic Style Historic Resources Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 25, 1989.

- Camp Peary, near Williamsburg, Virginia. During World War II, the US Navy used a portion of Camp Peary to house POWs. Within Camp Peary is Porto Bello, the hunting lodge of the last Royal Governor of Virginia. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 13, 1973 and has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Camp Popolopen, Highlands, New York. Now known as Camp Buckner, this area is currently part of the West Point Military Reservation. The United States Military Academy at West Point was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960. It has also been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Camp Ritchie, Cascade, Maryland. Both the Upper Lake and Lower Lake dams at Fort Ritchie have been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Camp Ruston, Grambling State University West Campus, Ruston, Louisiana. After its use as an Enemy Alien Internment Camp, Camp Ruston was one of the largest POW camps in the US. The Ruston POW Camp Buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places on December 13, 1991.

- Camp Shelby, Mississippi. Building 1071, also known as the White House, is the only surviving building from the World War II era at Camp Shelby. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 2, 1997.

- Douglas Prisoner of War Camp, Douglas, Wyoming. The surviving Officer’s Club building contains sixteen murals painted by Italian POWs. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 8, 2001.

- Eglin Army Air Field, Fort Walton Beach, Florida. POWs were held at Eglin Field and used to clean up Camp Pinchot. Both of these places are located on Eglin Air Force Base. Camp Pinchot and Eglin Field were added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 22, 1998.

- Fort Andrews, part of the Harbor Defenses of Boston, Peddock’s Island, Massachusetts. The fort housed Italian Service Unit workers. It is part of the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area, an NPS unit established on November 12, 1996.

- Fort Bliss, Texas. During World War II, Fort Bliss incarcerated several POWs. Fort Bliss Main Post Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 7, 1998. The remains of several enemy aliens and POWs who died at the Lordsburg, New Mexico enemy alien camp were moved to the Fort Bliss National Cemetery, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 2016. Several structures at Fort Bliss have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey, including the Post Hospital and several buildings associated with the William Beaumont General Hospital complex (one of the POW hospitals across the US). The Fort Bliss National Cemetery has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey.

- Fort D.A. Russel, Marfa, Texas. Building 98, the Officers’ Club and Bachelor Officers’ Quarters, contains several murals painted by German POWs. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 25, 2004. Fort D.A. Russell was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 14, 2006.

- Fort Hunt, Alexandria, Virginia. The site of a top-secret military intelligence operation known as P.O. Box 1142. Among the activities here were the interrogation of high value German POWs. Fort Hunt was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 26, 1980 and is part of the George Washington Memorial Parkway.

- Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. Several Nazi POWs were executed and buried at Fort Leavenworth for murdering other, anti-Nazi POWs. The murders took place at Camp Concordia, near Concordia, Kansas; Camp Gordon, Georgia; Camp Tonkawa, Oklahoma; and Papago Park, Arizona (Fort Leavenworth Historical Society n.d.; Hurt 2008: 337-338). Those executed were buried in the Fort Leavenworth Military Prison Cemetery. Fort Leavenworth was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on May 14, 1974.

- Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri. The German POW Stonework Historic District on the fort grounds was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places in 1987 (Jackson and Church 2017; Smith et al. 2006).

- Fort Lewis, DuPont, Washington. Fort Lewis housed POWs during World War II. The Locomotive Shelter and the Post Hospital have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort McClellan, Anniston, Alabama. POWs held here worked around the Fort, including doing stonework, woodwork, landscaping, and painting murals located within the Officers’ Club. The Fort McClellan World War II Housing Historic District, the Fort McClellan Ammunition Storage Historic District, the Fort McClellan Industrial Historic District, and the Fort McClellan Post Headquarters Historic District were added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 8, 2006.

- Fort McCoy, near Tomah, Wisconsin. POWs and enemy aliens were held here. Fort McCoy – including the hospital where incarcerated POWs and enemy aliens were treated – has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort Morgan State Armory, Fort Morgan, Colorado. During World War II, the armory swimming pool was covered and converted to a dining room for POWs who were living in Quonset huts in the armory parking area. The Fort Morgan State Armory was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 16, 2004.

- Fort Niagara, near Youngstown, New York. During World War II, POWs were held at Fort Niagara. Colonial Niagara was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960. The fort’s lighthouse, Fort Niagara Light, which was in operation during World War II, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 19, 1984.

- Fort Omaha, Omaha, Nebraska. Fort Omaha held POWs during World War II. Fort Omaha was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 27, 1974.

- Fort Ord, near Monterey Bay, California. The Soldiers’ Club at Fort Ord has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Fort Reno, near El Reno, Oklahoma. POWs housed at Fort Reno built the fort’s chapel, which remains standing. Several POWs are buried in the fort’s cemetery (Oklahoma Historical Society n.d.). Fort Reno was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 22, 1970.

- Fort Riley, Riley, Kansas. During WWII, POWs were held in the Camp Funston area of the Fort. The Main Post Area was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 1, 1974. Fort Riley has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey, including several individually documented buildings.

- Fort Robinson, near Crawford, Nebraska. This POW camp was located near the site of Red Cloud Agency (Fort Robinson History Center n.d.). The Fort Robinson and Red Cloud Agency Historic District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 1984 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 19, 1960.

- Fort Sam Houston, San Antonio, Texas. The fort hosted up to 1,000 POWs during World War II. After closing POW camps across the country, the Army moved the remains of POWs from camp cemeteries to federal cemeteries. The remains of POWs from eight camps in Texas, Arkansas, Louisiana, and Oklahoma were reinterred in the Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery (United States Department of Veterans Affairs n.d.). Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 2016; it has also been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey. Fort Sam Houston was designated a National Historic Landmark District on May 15, 1975.

- Fort Sheridan, Illinois. Fort Sheridan was the administrative headquarters for 46 POW camps in Michigan, Illinois, and Wisconsin. Fort Sheridan was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 29, 1980 and designated a National Historic Landmark on April 20, 1984.

- Gettysburg WWII POW Camp, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Formerly the McMillan Woods CCC Camp, during World War II it was used to house POWs. It is located on land that is now part of Gettysburg National Military Park. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. POWs were temporarily held in other locations, including the Gettysburg Armory, while the Gettysburg Camp was prepared. Gettysburg Armory was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 18, 1990.

- Griffith Park, Los Angeles, California. Camp Griffith Park, one of three former CCC camps here, served as a POW camp as well as a detention camp for suspected enemy aliens. The Griffith Park Zoo has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey.

- Honouliuli Internment Camp, Oahu, Hawai’i. Also known as the Central Pacific Camp (Frank and Seelye 2019: 61), this camp held POWs and enemy aliens. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 21, 2012 and designated a National Monument on February 24, 2015. On February 19, 2015 it was redesignated Honouliuli National Historic Site.

- Jefferson Barracks, Lemay, Missouri. POWs stationed here worked in a laundry that provided service for a number of army installations and two additional POW camps. Jefferson Barracks was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 1, 1972. Seven POWs are buried in the Jefferson Barracks National Cemetery, added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 9, 1998.

- Lake Wabaunsee, near Eskridge, Kansas. This POW camp was established in a former National Youth Administration camp (Clark 1985: 8-13). The Southeast and East Stone Arch Bridges from the era were listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 30, 2009.

- Maness Schoolhouse, Barling, Arkansas. The open porch on the back of the schoolhouse was built by POWs. They also constructed a large concrete slab and a stone BBQ pit here. The school was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 29, 2003.

- Marked Tree, Arkansas. A POW camp here provided labor to local farms. The Marked Tree Commercial Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 18, 2009.

- Michaux Park, Palestine, Texas. Theo Maffitt Sr. designed several buildings within the Michaux Park Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 28, 2004. During World War II, he served as Post Engineer at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas and for the Prisoner of War Camp at Tonkawa, Oklahoma where he oversaw its construction. Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 8, 2016; it has also been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey. Fort Sam Houston was designated a National Historic Landmark District on May 15, 1975.

- Old Bayfield County Courthouse, Bayfield, Wisconsin. Used as the county courthouse until 1892, POWs were housed here during World War II. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 27, 1974. It is currently the headquarters of Apostle Islands National Lakeshore.

- Papago Park, Phoenix, Arizona. Within the boundaries of Papago Park is Hunt’s Tomb, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 12, 2008. Built in 1932, it was present when the park was used to house POWs. Werner Drexler, captured from a German U-boat, was first sent to Fort Hunt, where he became an American agent. He was then sent to Fort Leonard Wood and then to Papago Park. Recognized here as a spy for the US, he was murdered. The seven POWs convicted of the murder were executed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas and buried in the Fort Leavenworth Military Prison Cemetery (Fort Leavenworth Historical Society n.d.).

- Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Commerce City, Colorado. POWs were held on the site of the Arsenal. It has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Roosevelt Addison Historic District, Tempe, Arizona. After closure, materials from the Papago Park Prisoner of War Camp were offered to veterans, including those settling in the Roosevelt Addison area of Tempe. The Roosevelt Addison Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 2, 2009.

- Rosewell, New Mexico. German POWs worked here to help channelize the North Spring River. In the walls of the channel, they embedded multicolored stones into the riprap, forming a large Iron Cross. Downtown Roswell was added to the National Register of Historic Places on May 16, 1985 (boundary increase: January 17, 2002).

- Sanchez Farmstead, Spuds, Florida. POWs from a nearby camp provided farm labor here. The Sanchez Farmstead was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 12, 2001.

- Schwartz Ballroom, Hartford, Wisconsin. The Schwartz Ballroom was leased to the US military as POW “Camp Hartford.” It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 20, 1998.

- Scotland Neck, North Carolina. Scotland Neck was an auxiliary POW camp of Fort Bragg (Frank and Seelye 2019: 129). The building used to house the POWs is within the Scotland Neck Historic District, added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 31, 2003.

- Stine Building, Alva, Oklahoma. The Stine Building was a recreation and dance hall for the personnel at the Prisoner of War camp located outside of Alva. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 21, 1982.

- Union Pacific Railroad Depot, Concordia, Kansas. POWs moving to and from POW Camp Concordia came through the town’s Union Pacific Railroad Depot. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 2004.

[15] Bryant 2019; Fort McCoy Public Affairs Office 2021.

[16] Sherman 2019.

[17] Sherman 2019. For archaeology done at World War II POW camps, see, for example: Barnes 2013, 2016, 2018a, 2018b, 2019; Bryant 2019; Farrell 2017; Jasinski n.d.; Morine 2016; Ross 2021: 605; Steinquest 2021; Stier 2019; and Sturkol 2023; Young 2013. See also Ruberto 2022.

[18] Garcia 2009; Litoff and Smith 1993; Sherman 2019.

[19] Worrall 1992: 147.

[20] Smith 2023; Worrall 1992: 148.

[21] Conti and Perry 2016; Struve 2022; Worrall 1992: 147.

[22] Bell 2022; Richards 1945.

[23] Hubbs 2001. Remains of World War II that survive on Wake Island, including the “98 Rock,” were designated a National Historic Landmark on September 16, 1985. Wake Island has been documented by the Historic American Landscapes Survey. Other civilians also found themselves held as Prisoners of War. Nellie Dyer, a member of the Imboden Methodist Episcopal Church, South was doing mission work during World War II when she was captured by the Japanese and held as a POW. The church in Imboden, Arkansas was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 30, 2004. Nellie Mae Kellogg Van Schaick (niece of the founder of Kellogg cereals) built a home in Pima, Arizona after returning from the Philippines. She and her family spent years as POWs during the war. Her home was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 30, 2011.

[24] Babauta 2023; Hofschneider 2020; Iwamoto 2020; United States House of Representatives 2006.

[25] Keady 2003; The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940. Civilian Public Service camps include (Yoder 2004):

CPS camps associated with the NPS:

- Bedford, Virginia: CPS Camp 121. Crew from this camp did work for the NPS, possibly along the nearby Blue Ridge Parkway.

- Belton, Montana (now West Glacier, Montana): CPS Camp No. 55. This Camp was located within Glacier National Park.

- Galax, Virginia: CPS Camp No. 39. Originally working on the Blue Ridge Parkway for the NPS, crew from this camp traveled to Sequoia National Park in May 1943. The Blue Ridge Parkway has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Gatlinburg, Tennessee: CPS Camp No. 108. Crew from CPS Camp No. 108 worked on projects for the National Park Service, including possibly nearby Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

- Hill City, South Dakota, CPS Camp No. 57. Nearby National Park units include Badlands and Wind Cave National Parks, Jewel Cave National Monument, and Mount Rushmore National Memorial.

- Luray, Virginia: CPS Camp No. 45 “Shenandoah National Park.”

- Lyndhurst, Virginia: CPS Camp No. 29, “Waynesboro, Virginia.” Crew from this camp worked at the Blue Ridge Parkway. The Blue Ridge Parkway has been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Marion, North Carolina: CPS Camp No. 19, “Buck Creek.” Originally assigned to the NPS Blue Ridge Parkway, in May 1943, they went to Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The Blue Ridge Parkway and Great Smoky Mountains National Park Roads and Bridges have been documented by the Historic American Engineering Record.

- Three Rivers, California: CPS Camp No. 107. Members of this camp worked on projects for the NPS. Nearby National Park units include Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks.

Civilian Public Service (CPS) Camps associated with state mental hospitals (many of the CPS workers at these hospitals were appalled by the treatment of psychiatric patients. Several snuck in cameras to document the situation, and a selection were published in Life magazine in May 1946. The result was outrage and changes in how patients were treated (Maisel 1946; Martin 2020). Note that many of the historic names of these hospitals are no longer considered appropriate):

- Central Ohio Lunatic Asylum, Columbus, Ohio: CPS Camp No. 73, “Columbus State Hospital.” It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 24, 1986.

- Connecticut General Hospital for the Insane, Middletown, Connecticut: CPS Camp No. 81, “Connecticut State Hospital.” The hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 29, 1985.

- Eastern Washington Hospital, Medical Lake, Washington: CPS Camp No. 75, “Medical Lake Hospital.” Roosevelt Hall on the campus of the hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 8, 1997.

- Hudson River State Hospital, Poughkeepsie, New York: CPS Camp No. 144, “Hudson River State Hospital.” The Main Building of the hospital was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 29, 1989 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 30, 1989.

- Iowa Hospital for the Insane, Independence, Iowa: CPS Camp No. 137, “Independence State Hospital.” The hospital has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Kalamazoo Regional Psychiatric Hospital, Kalamazoo, Michigan: CPS Camp No. 120, “Kalamazoo State Hospital.” The State Hospital Gatehouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 1983; the Hospital Water Tower was listed on March 16, 1972. Kalamazoo State Hospital has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Logansport State Hospital, Logansport, Indiana: CPS Camp No. 139, “Logansport State Hospital.” The Women’s Infirmary at the hospital has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Maine Insane Hospital, Augusta, Maine: CPS Camp No. 88, “Augusta State Hospital.” It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 19, 1982 (boundary increase: August 2, 2001).

- New Jersey State Asylum for the Insane at Morris Plains, New Jersey: CPS Camp No. 77, “Greystone Park State Hospital.” The hospital’s Illumination Gas Plant was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 9, 2000.

- New Jersey State Village for Epileptics, Skillman, New Jersey: CPS Camp 136. Maplewood, the superintendent’s residence, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 24, 2000.

- Northern Ohio Lunatic Asylum, Cleveland, Ohio: CPS Camp No. 69, “Cleveland State Hospital.” It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 30, 1973. It was demolished in January 1978 and has been withdrawn.

- Norwich State Hospital, Norwich, Connecticut: CPS Camp No. 68, “Norwich Hospital.” The Norwich Hospital District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 22, 1988.

- Oregon State Insane Asylum, Salem, Oregon: CPS Camp No. 38, “Salem Hospital” (camp suspended before it opened). Oregon State Hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on February 28, 2008. The hospital’s North Campus has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Pennsylvania State Lunatic Hospital, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: CPS Camp No. 93, “Harrisburg State Hospital.” It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on January 8, 1986.

- Southern Ohio Lunatic Asylum, Dayton, Ohio: CPS Camp No. 70, “Dayton State Hospital.” It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 15, 1979 and has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey. Dayton, Ohio (Montgomery County) is an American World War II Heritage City.

- Southwestern State Hospital, Marion, Virginia: CPS Camp No. 109, “Southwestern State Hospital.” The Henderson Building on the hospital campus was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 21, 1990.

- Springfield State Hospital, Sykesville, Maryland: CPS Camp No. 47, “Springfield State Hospital.” The women’s facilities, Warfield Complex, Hubner & T Buildings, were added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 2, 2000.

- Utah State Hospital, Provo, Utah: CPS Camp No. 79, “Utah State Hospital.” The Recreation Center and the Superintendent’s Residence at the hospital were listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 9, 1986.

- Utica State Hospital, Utica, New York: CPS Camp No. 65, “Utica State Hospital” (camp suspended before it opened). Listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 26, 1971; the main building was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 30, 1989.

- Vermont Asylum for the Insane, Brattleboro, Vermont: CPS Camp No. 87, “Brattleboro Retreat.” Brattleboro Retreat was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on April 12, 1984.

- Warren State Hospital, Warren, Pennsylvania: CPS Camp No. 83, “Warren State Hospital.” The Warren State Hospital Farm Colony Building has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Western State Hospital, Staunton, Virginia: CPS Camp No. 44, “Western State Hospital.” Western State Hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on November 25, 1969 (boundary increases: February 21, 2007; July 24, 2007; and March 23, 2010).

- Western State Hospital, Steilacoom, Washington: CPS Camp No. 51. Fort Steilacoom, including Western State Hospital, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on November 11, 1977. The former Officers’ Houses have been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Mansfield Training School and Hospital, Mansfield, Connecticut: CPS Camp No. 91, “Mansfield State Training School & Hospital.” It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on December 22, 1987.

- National Orphans’ Home, Tiffin, Ohio: CPS Camp No. 147. The National Orphans’ Home, Junior Order United American Mechanics was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 1, 1990.

- Rosewood Center, Owings Mills, Maryland: CPS Camp 102, “Rosewood State Training School.” Portions of the Rosewood Center are located within the Caves Valley Historic District, listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 20, 1988.

- Utah State Training School, American Fork, Utah: CPS Camp No. 127. The Utah State Training School Amphitheater and Wall were listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 7, 1994.

Civilian Public Service (CPS) Camps associated with the “human guinea pig experiments” by the Office of Scientific Research & Development and (where noted) the Office of the Surgeon General (Mennonite Central Committee 2015; Time Magazine 1945; Yoder 2010):

- Indiana University, Bloomington: CPS Camp 115.15, “Indiana University.” CPS members were subjects in climatology research. The Old Crescent area of the university was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on September 8, 1980.

- City Hospital, Roosevelt Island, New York: CPS Camps 115.3, 115.4, and 115.5 “Welfare Island Hospital.” Members of CPS Camp 115.3 took part in altitude pressure experiments; 115.4 were subjects in life raft ration experiments; and 115.5 were subjects in high altitude experiments. The City Hospital was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 16, 1972 and has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Columbia University, New York City: CPS Camp No. 115.25 “Columbia University.” Members were subjects in malaria experiments. Designated buildings on the campus include: Low Memorial Library (National Historic Landmark, December 23, 1987); Philosophy Hall (National Historic Landmark, July 31, 2003); Pupin Physics Laboratory (listed on the National Register on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 21, 1965); Casa Italiana (listed on the National Register on October 29, 1982); and Earl Hall (listed on the National Register on March 12, 2018).

- Cornell University, Ithaca, New York: CPS Camp No. 115.27 “Cornell University.” Members were subjects in bed rest and cold condition experiments. Several buildings on the Cornell Campus are listed on the National Register of Historic Places including: Andrew Dickinson White House (listed December 4, 1973); Morill Hall (listed on the National Register on October 15, 1966 and designated a National Historic Landmark on December 21, 1965); and Bailey Hall, Caldwell Hall, Comstock Hall, Rice Hall, Fenrow Hall, and Wing Hall (listed as part of the New York State College of Agriculture Multiple Property Submission, September 24, 1984).

- Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts: CPS Camps 115.10, 115.11. and 115.24 “Massachusetts General Hospital.” Members of these PSC Camps took part in sea water and malaria experiments. The Bulfinch Building on the hospital campus was designated a National Historic Landmark on December 30, 1970 and has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota: CPS Camp 115.32 “Mayo Clinic.” These CPS members took part in aero-medical experiments. The Plummer Building on the Mayo Clinic campus was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 4, 1969 and designated a National Historic Landmark on August 11, 1969 (link is archived). It has also been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Metropolitan Hospital, Roosevelt Island, New York: CPS Camp 115.6 “Metropolitan Hospital.” Members took part in frostbite experiments. The Octagon, part of the Metropolitan Hospital complex on the island (formerly the New York City Mental Health Hospital / New York City Lunatic Asylum), was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on March 16, 1972. The Insane Asylum complex has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

- Ohio State University, Columbus: CPS Camp 115.20 “Ohio State University.” Members of this camp took part in physiology experiments. Five buildings on campus have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places: the Old Ohio Union (Hale Hall, listed April 20, 1979); University Hall, Hayes Hall, and Orton Hall (listed July 16, 1970; University Hall was demolished in 1971); and Ohio Stadium (listed March 22, 1974).

- Pinehurst, North Carolina: CPS Camp 115.33 and 140.1. Members of these camps were subjects in experiments on atypical pneumonia by the Office of the Surgeon General. Pinehurst Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 14, 1973. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on June 19, 1996.

- Stanford University, California: CPS Camp 115.9 “Stanford University.” Members of this camp were subjects for malaria experiments. The Hanna-Honeycomb House (listed on the National register of Historic Places on November 7, 1978 and designated a National Historic Landmark on June 29, 1983) and the Lou Henry Hoover House (listed on the National Register on January 30, 1978 and designated a National Historic Landmark on February 4, 1985) are located on the Stanford campus.

- University of Illinois, Urbana: CPS Camp 115.30 “University of Illinois.” Members of this camp were subjects for heat and tropical conditions experiments. Several buildings on the campus have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places, including: Harker Hall (listed November 19, 1986); Louise Freer Hall, Main Library (listed as part of the University of Illinois Buildings Designed by Charles A. Platt Multiple Property Submission); and the Astronomical Observatory (listed on November 6, 1986; designated a National Historic Landmark on December 20, 1989).

- University of Michigan, Ann Arbor: CPS Camps 115.12 and 115.16 “University of Michigan.” Members of these CPS Camps were subjects in physiological hygiene and weather experiments. The University of Michigan Central Campus was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on June 15, 1978.

- University of Minnesota, Minneapolis: CPS Camp 115.17 “University of Minnesota: Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene” and CPS Camp 115.18 “University of Minnesota.” Members of these CPS camps took part in starvation and thiamine experiments. The University of Minnesota Old Campus was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on August 23, 1984; the Northrop Mall Historic District, also on the university campus, was listed on January 19, 2018.

- University of Southern California, Los Angeles: CPS Camp 115.2 “University of Southern California.” Members of the CPS camp were subjects in altitude pressure experiments. The University of Southern California Historic District was added to the National Register on July 14, 2015.

Civilian Public Service (CPS) Camps associated with other places:

- Lyons VA Medical Center, Lyons, New Jersey: CPS Camp No. 80 “Lyons Veterans Hospital.” The Lyons Veterans Administration Hospital was listed on the National Register on July 3, 2013.

[26] Kennedy 1999: 633; Martin 2020; Yoder 2007.

[27] Keady 2003; Martin 2020. Prisoners found themselves in federal prisons and county jails, including (Bennett 2003: 414, 419; Hirsch 1950: 62, 63; Hopkins 2010: 249-250; Lyon 2020; Muller 2020; Ross 2021: 604; Smith 2023):

- Danbury Correctional Institution, Danbury, Connecticut (see Schoenfeld 1950 for a publication by Conscientious Objectors incarcerated at Danbury.)

- Federal Penitentiary at Ashland, Kentucky

- Federal Penitentiary at Chillicothe, Ohio

- Federal Prison Camp, Mill Point, West Virginia

- Leavenworth Federal Prison, Kansas

- Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary, Lewisburg, Pennsylvania

- Marion County Jail, Indianapolis, Indiana

- McNeil Island Federal Penitentiary, Steiliacoom, Washington

- Sandstone Federal Penitentiary, Sandstone, Minnesota

- Tuscon Federal Prison Camp (also known as the Catalina Federal Honor Camp), Arizona

- West Street New York Federal Detention Center, New York City

[28] Scheiber and Scheiber 2016: 1, 2020.

[29] Scheiber and Scheiber 2020.

[30] Scheiber and Scheiber 2016: 4, 2020.

[31] Scheiber and Scheiber 2020.

Babauta, Leo (2023) “War Atrocities: Manenggon Concentration Camp.” Guampedia, January 7, 2023.

Barnes, Jodi (2019) “Galvanized Metal Etching from Camp Monticello.” Artifact of the Month – November 2019, Arkansas Archeological Survey.

--- (2018a) “Nails, Tacks, and Hinges: The Archaeology of Camp Monticello, a World War II Prisoner of War Camp.” Southeastern Archaeology 37(1): 1-21.

--- (2018b) “Madonna del Prignioniero Prega per Noi: An Intimate Archaeology of a World War II Italian Prisoner-of-War Camp.” Historical Archaeology 52(3): 561-579.

--- (2016) “From Caffé Latte to Catholic Mass: the Archeology of a World War II Prisoner of War Camp.” In Research, Preservation, Communication: Honoring Thomas J. Green on his Retirement from the Arkansas Archaeological Survey, edited by MB Trubitt, p. 183-207. Research Series No. 67. Arkansas Archaeological Survey.

--- (2013) “Mapping Camp Monticello: Archeology of a World War II Italian Prisoner of War Camp.” Field Notes: Newsletter of the Arkansas Archeological Society 375: 3-10.

Bell, Michael S. (2022) “Call for Action and the Liberation of the Philippines.” National World War II Museum, July 25, 2022.

Bennett, Scott H. (2003) “Free American Political Prisoners: Pacifist Activism and Civil Liberties, 1945-48.” Journal of Peace Research 40(4): 413-433.

Bryant, Paula (2019) “Preserving What Remains: Fort Sheridan WWII POW Branch Camps in the Cook County Forest Preserved in Illinois.” Paper presented at Preserving U.S. Military Heritage: World War II to the Cold War, Fredericksburg, Texas, June 2019.

Camp, Stacey (2019) “Vision and Ocular Health at a World War II Internment Camp.” World Archaeology 50(3): 530-546.

--- (2012) “The Archeology of Japanese American Internment.” National Park Service, October 4, 2012.

Clark, Penny (1985) “Farm Work and Friendship: The German Prisoner of War Camp at Lake Wabaunsee.” MA Thesis, Emporia State University.

Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (1982) Personal Justice Denied Part 1, December 1982. Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Congressional Report.

Conti, Flavio G. and Alan R. Perry (2016) Italian Prisoners of War in Pennsylvania: Allies on the Home Front, 1944-1945. Rowman & Littlefield.

Densho (2023) “About the Incarceration.” Densho.

Ernst, Cheryl (2011) “The Internment Camp in West O’ahu’s Backyard.” Mālamalama: The Light of Knowledge November, 2011.

Farelly, Elly (2019) “Not Widely Known – The Internment Camps of Germans in America During WWII.” War History Online, January 26, 2019.

Farrell, Mary M. (2017) Honouliuli POW and Internment Camp: Archaeological Investigations at Jigoku-Dani 2006-2017. Japanese Cultural Center of Hawai’i, December 2017.

Fort Leavenworth Historical Society (n.d.) “German POW Execution.” Fort Leavenworth Historical Society (archived).

Fort McCoy Public Affairs Office (2021) “Fort McCoy: ArtiFACT: Internment, POW Camp Map.” Defense Visual Information Distribution Service, May 28, 2021.

Fort Robinson History Center (n.d.) “Brief History of Fort Robinson.” History Nebraska.

Frank, Dave and David E. Seelye (2019) The Complete Book of World War II USA POW & Internment Camp Chits: Prisoner of War Money in the United States. Coin & Currency Institute, Williston, VT.

Gage, Beverly (2022) “How World War II Helped Forge the Modern FBI.” Smithsonian Magazine, November 22, 2022.

Garcia, J. Malcolm (2009) “German POWs on the American Homefront.” Smithsonian Magazine, September 15, 2009.

German American Internee Coalition (2023) “State Department Related Sites: Hotels and Resorts.” Internment Camps, German American Internee Coalition (archived).

Hinnershitz, Stephanie (2022a) “The Wartime Internment of Native Alaskans.” National World War II Museum, June 30, 2022.

--- (2022b) “Lunchbox Lecture: Mealtime in the Mass Halls: Food in the Japanese American Incarceration Camps of World War II.” National World War II Museum, August 3, 2022.

--- (2021a) Japanese American Incarceration: The Camps and Coerced Labor During World War II. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia.

--- (2021b) “Proclamation 2527 and the Internment of Italian Americans.” National World War II Museum, December 13, 2021.

Hirsch, Charles B. (1950) “Conscientious Objectors in Indiana During World War II.” Indiana Magazine of History 46(1): 61-72.

Hofschneider, Anita (2020) “Guam Residents Who Suffered 1940s War Atrocities to Receive Compensation.” PBS Newshour, February 27, 2020.

Hoh, Anchi (2018) “Good Neighbors: Stories from Latin America in World War II.” 4 Corners of the World: International Collections at the Library of Congress, August 28, 2018.

Hopkins, Mary R. (ed.) (2010) Men of Peace: World War II Conscientious Objectors. Producciones de la Hamaca, Caye Caulker, Belize.

Hubbs, Mark E. (2001) “Massacre on Wake Island.” Naval History Magazine 15(1).

Hurt, R. Douglas (2008) The Great Plains During World War II. University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln.

Imai, Shiho (2020) “Korematsu v. United States.” Densho Encyclopedia, July 29, 2020.

Iwamoto, Nicholas (2020) “Caught Between the Sun and Stars: The Chamorro Experience During the Second World War.”Hohonu 18: 11-18.

Jackson, Sarah Marie and Jason Church (2017) Fort Leonard Wood German POW Stonework: Maintenance and Repair. US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center.

Jasinski, Marek E. (n.d.) “German Soldiers on Both Sides of Barbed Wire Fences. Comparative Studies of WWII POW Camps in Norway and Texas, USA.” Conference presentation, European Association of Archaeologists 2015, Glasgow, September.

Keady, Bonnie (2003) “The Good War and the Bad Peace: Conscientious Objectors in World War II.” MSS, Department of History, Western Oregon University.

Kennedy, David M. (1999) Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press, New York.

Krammer, Arnold (1983) “Japanese Prisoners of War in America.” Pacific Historical Review 52(1): 67-91.

Litoff, Judy Barrett and David C. Smith (1993) “’To the Rescue of the Crops’: The Women’s Land Army During World War II.” Prologue 25(4).

Lyon, Cherstin M. (2020) “Tucson (detention facility).” Densho Encyclopedia, Aug. 24, 2020.

Maisel, Albert Q. (1946) “Bedlam 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals are a Shame and a Disgrace.” Life, May 6, 1946, p. 102-118.

Martin, Kali (2020) “Alternative Service: Conscientious Objectors and Civilian Public Service in World War II.” National World War II Museum, October 16, 2020.

Mennonite Central Committee (2015) “Ethics and the Guinea Pig Experiments.” Civilian Public Service.

Morine, Christopher Michael (2016) “German POWs Make Colorado Home: Coping by Craft and Exchange.” MA thesis, University of Denver.

Muller, Eric L. (2020) “Draft Resistance.” Densho Encyclopedia, August 24, 2020.

National Archives and Records Administration (2022) “Executive Order 9066: Resulting in Japanese-American Incarceration (1942).” National Archives and Records Administration: Milestone Documents, January 24, 2022.

--- (2021) “World War II Enemy Alien Control Program Overview.” National Archives and Records Administration: Research Our Records, January 7, 2021.

National Park Service (2023) “A Brief History of Japanese American Relocation During World War II: Excerpts from Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites.” National Park Service, March 20, 2023.

--- (2021a) “Evacuation and Internment.” National Park Service, November 10, 2021.

--- (2021b) “World War II Aleut Relocation Camps in Southeast Alaska – Introduction.” National Park Service, February 14, 2021.

Niiya, Brian (2021a) “Ask a Historian: How Many Japanese Americans Were Incarcerated During WWII?” Densho Catalyst, June 2, 2021.

--- (2021b) “Old Raton (detention facility).” Densho Encyclopedia, July 6, 2021.

--- (2020) “Voluntary Evacuation.” Densho Encyclopedia, July 29, 2020.

Oklahoma Historical Society (n.d.) “Fort Reno.” The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture.

Rakoczy, Lila (2019) “Preserving Second World War Internment History: A Texas Perspective.” Paper presented at Preserving U.S. Military Heritage: World War II to the Cold War conference, June 4-6, 2019, Fredericksburg, Texas.

Richards, Peter (1945) “The Liberation Bulletin of Philippine Internment Camp No. I at Santo Tomas University, Manila, Philippines, February 3rd, 1945.” Newsletter. Cover; Page 1; Page 2; Page 3; Page 4; Page 5; Page 6; Page 7.

Robinson, Greg (2020) “Ex Parte Mitsuye Endo (1944).” Densho Encyclopedia, July 15, 2020.

Rosenfeld, Alan (2015) “German and Italian Detainees.” Densho Encyclopedia, July 29, 2015.

Ross, Douglas E. (2021) “A History of Japanese Diaspora Archaeology.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 25: 592-624.

Ruberto, Laura (2022) “Creative Expression and the Material Culture of Italian POWs in the United States During World War II.” Material Culture Review 92/93: 3-32.

Scheiber, Harry N. and Jane L. Scheiber (2020) “Martial Law in Hawai’i.” Densho Encyclopedia, July 22, 2020.

--- (2016) Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai’i during World War II. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

Schoenfeld, Howard (1950) “The Danbury Story.” In Prison Etiquette: The Convict’s Compendium of Useful Information” by The Inmates, p. 12-27. Collection of Western Connecticut State University Archives, Rare Books.

Sherman, Richard L. (2019) “Italian, Japanese and Nazi POWs in America: Strangers Within Our Gates.” Warfare History Network, October 2019.

Shew, Dana Ogo (2010) “Feminine Identity Confined: The Archaeology of Japanese Women at Amache, a WWII Internment Camp.” MA thesis, University of Denver.

Smith, Adam D., Sunny Stone, Susan I. Enscore, Marcia Harris, Christella Lai, William D. Meyer, and Jacqueline Wolke (2006) Fort Leonard Wood German POW Stonework Context and Survey. US Army Corps of Engineers, Engineer Research and Development Center.

Smith, C. Mark (2023) “World War II in the Tri-Cities: How Federal Convicts and Italian POWs Helped Support the U.S. War Effort.” HistoryLink, April 2, 2023.

Steinquest, Ethan (2021) “Fort Campbell Works to Preserve German POW Camp History.” U.S. Army, December 9, 2021.

Stier, Will (2019) “Camp Au Train.” Military History of the Upper Great Lakes, October 24, 2019.

Struve, Mark (2022) “Italian POWs Worked on RIA During World War II.” United States Army, April 14, 2022.

Sturkol, Scott (2023) “Fort McCoy ArtiFACT: New Research on Fort McCoy’s World War II-Era Prisoner of War Camp.” U.S. Army, August 18, 2023.

Swader, Paul (2015) “An Analysis of Modified Material Culture from Amache: Investigating the Landscape of Japanese American Internment.” MA thesis, University of Denver.

Taylor, David A. (2017) “During World War II, the US Saw Italian Americans as a Threat to Homeland Security.” Smithsonian Magazine, February 2, 2017.

Texas Historical Commission (2023) “Dodd Field at Fort Sam Houston Enemy Alien Detention Station.” Texas Historical Commission, January 4, 2023.

--- (n.d.) “Japanese, German, and Italian American Enemy Alien Internment.” Texas Historical Commission.

Time Magazine (1945) “Medicine: The Conscientious Guinea Pigs.” Time Magazine, December 10, 1945.

United States Department of Veterans Affairs (n.d.) “POW Headstone Descriptions and Images.” United States Department of Veterans Affairs, National Cemetery Administration.

United States House of Representatives (2006) “House Report 109-437: Guam World War II Loyalty Recognition Act.” United States House of Representatives, June 9, 2006.

Vernon E. Jordan Law Library (2023) “Historical Actions Against Immigrants: Internment Camps During World War II.” A Brief History of Civil Rights in the United States, January 6, 2023.

Worrall, Janet E. (1992) “Reflections on Italian Prisoners of War: Fort Wadsworth, 1943-1946.” Italian Americana 10(2): 147-155.

Yoder, Anne M. (2010) Human Guinea Pigs in CPS Detached Service, 1943-1946. Swarthmore College Peace Collection, November 2010.

--- (2007) “Conscientious Objectors.” Peace History Resources Online, TriCollege Libraries Research Guides.

--- (2004) “List of CPS Camps in Camp Number Order.” Swarthmore Peace Collection, December 2004.

Young, Allison M. (2013) “An Historical Archaeological Investigation of the Indianola Prisoner of War Camp in Southwestern Nebraska.” MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska – Lincoln.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIEnemies on the Home Front

The Home Front During World War IIEnemies on the Home FrontNot only were there several attacks directly on the home front by Axis troops, there were spies planted throughout the US.

-

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime Economy

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime EconomyThe US economy grew during the war, and pop culture boomed. But it wasn't a "glittering consumer's paradise" for everyone.

-

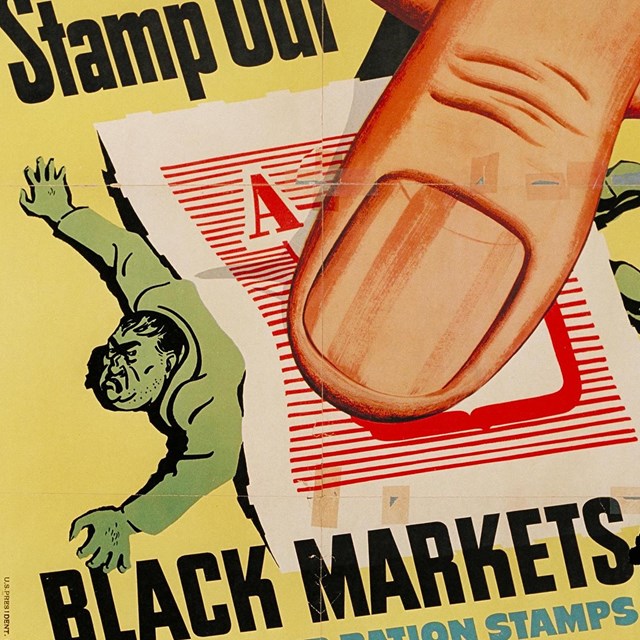

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black Markets

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black MarketsDespite rationing and other limits on goods during the war, some people figured out how to profit and get what they wanted outside the law.

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- wwii home front

- wwii homefront

- italian american

- german american

- japanese american

- latin american

- asian american and pacific islander history

- indigenous history

- native american history

- alaska native history

- incarceration

- prisoners of war

- pow

- latin america

- hawaii

- european history

- labor history

- government history

- military history

- west virginia

- virginia

- national register of historic paces

- national historic landmark

- historic american buildings survey

- historic american engineering record

- historic american landscape survey

- california

- illinois

- mississippi

- ohio

- connecticut

- iowa

- michigan

- maine

- oregon

- colorado

- kentucky

- kansas

- missouri

- wyoming

- louisiana

- arizona

- texas

- montana

- tennessee

- new jersey

- wisconsin

- ccc

- indiana

- minnesota

- maryland

- florida

- massachusetts

- south dakota

- north carolina

- oklahoma

- georgia

- alabama

- washington

- nebraska

- pennsylvania

- new mexico

- vermont

- incarceration camp

- tule lake

- granada

- amache

- heart mountain

- jerome

- manzanar

- minidoka

- poston

- rohwer

- topaz

- arkansas

- utah

- panama canal zone

- new york

- legal history

- alaska

- wake island

- guam

- philippines

- awwiihc

- american world war ii heritage city

- dayton

- history of medicine