Last updated: February 14, 2025

Article

The American Home Front During World War II: The Economy

Life Magazine, September 24, 1945, p. 127.

Popular Culture

Perhaps not surprisingly, the war dramatically shaped popular culture. Posters about supporting the war effort were everywhere. Broadcasters transmitted real-time war news directly into homes with radios. Images of the war were everywhere in newspapers, magazines, and even in newsreels that played before films in the theaters. Books, movies, radio shows, and music all carried pro-war and pro-American messages. [4]

Collection of the author.

There was social pressure during the war for people to show their patriotism. Some displayed service flags and Victory Home decals and wore sweetheart jewelry. Others drank the Cuba Libra cocktail, popular after the Andrews Sisters entertained troops with the “Rum and Coca-Cola” song. [7] Sweetheart jewelry – a revival from World War I – was mostly made of plastic to conserve metals. Bracelets, brooches, pins, lockets, rings, and necklaces displayed military emblems, American eagles, and service stars. Wearing sweetheart jewelry demonstrated patriotism, and served as a reminder of loved ones in service. It was also a source of fashion and accessorizing that was acceptable during wartime restrictions. In some cases, women used sweetheart jewelry to show that they were “taken” – that their husband, boyfriend, or fiancé was serving in the military. [8] Businesses also demonstrated their patriotism to the public in advertisements, but also to their employees through bond drives, display of service flags, and displaying posters. [9]

Collection Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (MO 2005.13.34.26.3).

Labor

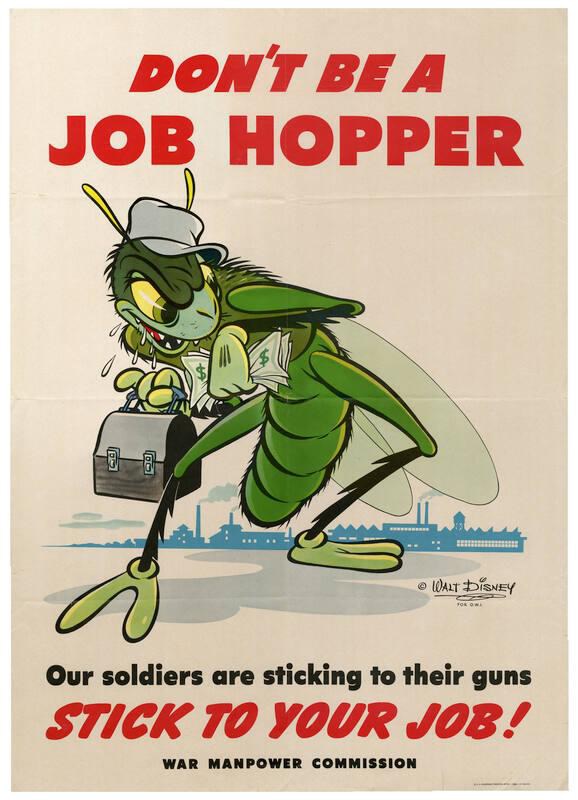

Even with restrictions on driving personal vehicles and civilian public transit, Americans during World War II were “frantically mobile.” The movement of people before December 1941 was nothing compared to what happened after Pearl Harbor. Men between ages 18 and 64 were required to register, and military service was extended to the duration of the conflict plus six months. [10] In 1942 alone, the military more than doubled, from 1.8 million to 3.9 million, pulling the remaining unemployed workers of military age into service. The government awarded over $100 billion (about $1.9 trillion in 2023 dollars) in military contracts in the first six months. To entice workers to their factories, businesses raised wages. Many farmers left their fields to work in industry, and laborers hopped from job to job chasing higher paychecks. To put a stop to this, the federal government formed the War Manpower Commission, which took over control of allocating civilian workers. [11] To help stabilize the labor market and support military production, union leaders agreed not to strike during the war. Despite their promise, there were a handful of strikes. Many of these were by white workers protesting Black war workers moving into high paying jobs. [12]Agricultural Workers

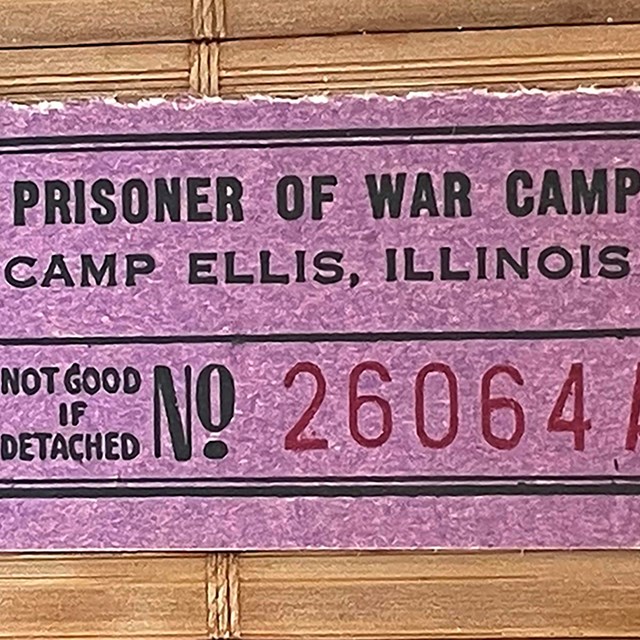

With millions of Americans serving overseas and millions more working in war industries, there was a shortage of agricultural labor. Further complicating the problem was an increased demand for food to feed citizens at home, the US military, and to provide food to Allied forces. In 1942, some crops died in the fields for lack of labor. To help address the shortage, the government created the United States Crop Corps and launched the Bracero program. They also leased out as many as 265,000 Prisoners of War and granted furloughs to about 26,000 Americans of Japanese descent incarcerated at War Relocation Centers to work on nearby farms. Approximately 6,200 conscientious objectors went to work in agricultural fields, and thousands of active service members were furloughed to work their family farms. [13]United States Crop Corps

Members of the Crop Corps worked the fields, managed livestock, and harvested and preserved crops. Two specific programs were targeted at youth and women. The Victory Farm Volunteers was for youth ages 11 to 17. A total of 2.5 million urban youth worked on farms during the war, with about 20% of them living with the farmers or in a nearby camp. [14] The Women’s Land Army began recruiting members even before Pearl Harbor -- at the insistence of Eleanor Roosevelt. About 1.5 million women joined the Women’s Land Army in World War II. Most members had no agricultural training, but learned on the job. Men who were past the draft age also took part. [15]There were problems with the program. Not all farmers were keen to have inexperienced people working on their farms. In the Midwest, there was also a feeling that city women were immoral. As the war progressed, and farmers had increasing experience with the Crop Corps, their skepticism waned. Many camps were substandard, and lacked basics like laundry facilities or enough toilets. Participants also had to pay their room and board – which sometimes exceeded their pay. And there were racial tensions, including southern states choosing to exclude women of color from the program. [16]

Collection of the National Museum of American History (1998.0197.01).

The Bracero Program

Mexicans were among the almost 230,000 temporary foreign agricultural workers brought to the US during the war. [17] The Bracero program began in September of 1942, and by 1944 over 62,000 had come to the US under the program. The agreement guaranteed wages, health care, adequate housing, and food (board). [18] Braceros worked in 38 states across the country, and required to return to Mexico once they finished their 6 or 12 month contracts. Thousands more – likely exceeding the number that came legally -- came through unauthorized channels. Both farmers and Mexican workers realized they could keep more money by working outside the legal system. [19]While many farmers appreciated the work they did, many Braceros suffered discrimination, poor health care, substandard housing, violence, and wage theft.[20] Despite their treatment and the backbreaking work, many Braceros kept working. They were hoping to make more in the US than they could in Mexico, and many sent money home to support their families. Angered and frustrated by the abuses they faced, some Braceros organized. They protested, rallied public support, and called for the end of the program. Their eventual success was integral to the farmworker movement associated with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. When the Bracero program was finally abolished in 1964, almost 4.5 million Mexicans had taken part.[21]

Life Magazine.

Women in the Workforce

Among war workers were six million women – largely older and married – new to the labor market. Supporting the war effort, they also earned money to offset wages lost when their male family members went to war. Women worked as welders, police officers, munitions makers, and clerks. [22] Many already in the workforce quit their jobs and moved into defense work. Among these were over 400,000 African American domestic servants. [23] Across the board, employers paid women less than they did men in the same jobs. And, despite the popularity of Rosie the Riveter, it was “understood” that these women would be out of work when the servicemen returned. [24]This “understanding” came with expectations that women would go back to being more traditionally feminine. This meant wearing dresses, staying at home and keeping house. These expectations are evident in advertising what the US was fighting for (i.e. in ads for War Bonds) and in ads placed by manufacturers who had converted their production for the war effort. In publication after publication, companies kept themselves in front of consumers, promising they would be back after the war to help the public create the ideal life they had fought for. These images almost exclusively portray a white, middle class, nuclear family future, despite the significant role that intergenerational families, working class people, and people of color played in winning the war. They were also adamantly heterosexual, even though LGB people were able to find each other and form community due to the patterns of population movement and single-gender spaces. [25]

Housing

By the end of the war, one in every 5 Americans had moved. [26] The largest loss of population was in the South. Almost 1.5 million Black residents relocated to states in the North and West in the Second Great Migration. [27] In many places, despite the laws enacted during the war, African Americans found themselves discriminated against in the workplace and in housing. [28] Violating its own policies of nondiscrimination, the federal government housed some African American workers in segregated neighborhoods. In Oak Ridge, Tennessee, African Americans working for the Manhattan Project lived in small, substandard housing units called hutments. [29]

Collection Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum (MO 2005.13.34.297).

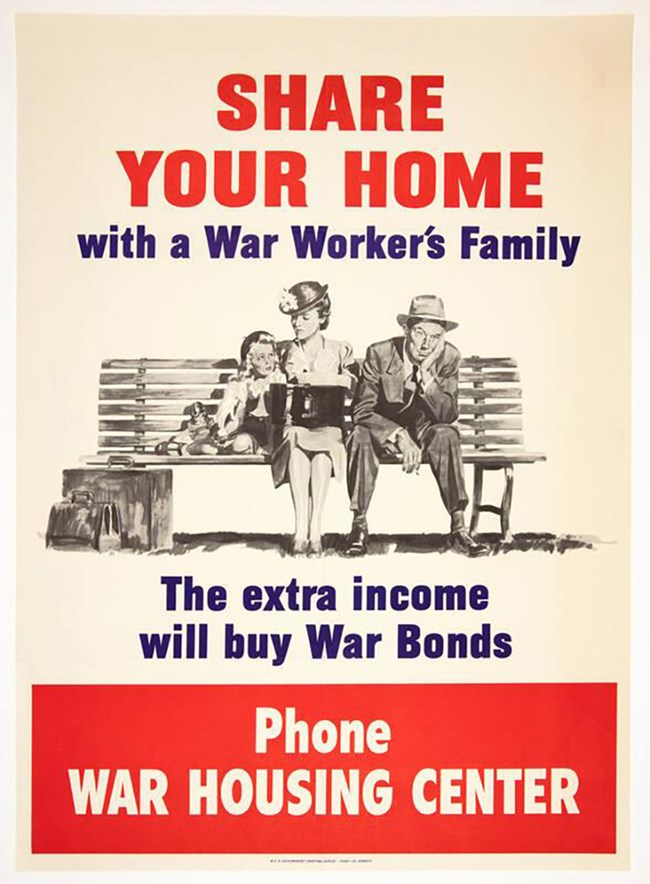

Those with children and those who were not white often found themselves unable to find housing. And when they did, it was often terrible.[33] With high demand and low supply, landlords raised rents, some doubling almost overnight. The government quickly put rent controls in place in these areas, and eventually began building war worker housing.[34] In the case of the Manhattan Project Sites, the government displaced entire communities to build secret cities to house workers. Government-built housing developments were largely designed to be temporary, and were built to match, with “paper thin walls and shoddy build quality.”[35]

Across the country, Americans found themselves living in new circumstances. As well as those moving to industrial centers to work, more than 16 million service members traveled to training and embarkation areas often far from home. [36] Some people bristled at living and working around people they would not have before the war. In some places, the influx of workers was seen as “a menace from the outside” or an “invasion.”[37] Tensions routinely fell along racial lines, and race riots, protests, and lynchings took place across the country. These included the Zoot Suit Riot of 1943 in Los Angeles and other violence in Alabama, Indiana, Louisiana, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Washington, DC – to name a few.[38] Whites violently protested African Americans moving into war housing – even when that housing was built specifically for Black war workers. At the Sojourner Truth Housing Project in Detroit, military and police moved in. At a shipyard in Mobile, Alabama, white workers rioted when the company promoted 12 Black workers. In Pennsylvania, the Army took control of the Philadelphia Transit Company after white workers went on strike protesting the promotion of eight Black porters to drivers. Race riots in Detroit left 35 people (the majority Black) dead, over 700 wounded, and 1,300 arrested.[39]

The upheaval brought by the war also affected the makeup of individual households. Parents and grandparents took in mothers, mothers-in-law, and children whose husbands and fathers had gone to war. While the women worked, the grandparents (usually the grandmother) took care of the children.[40] It was common to have multiple families living in a single multi-generational household.[41] Where this was not possible, federal and local centers opened to take care of children who would otherwise be left on their own. School lunch programs also expanded, ensuring that children were receiving adequate nutrition.[42]

Life Magazine, April 3, 1944, p. 130.

Battling Inflation

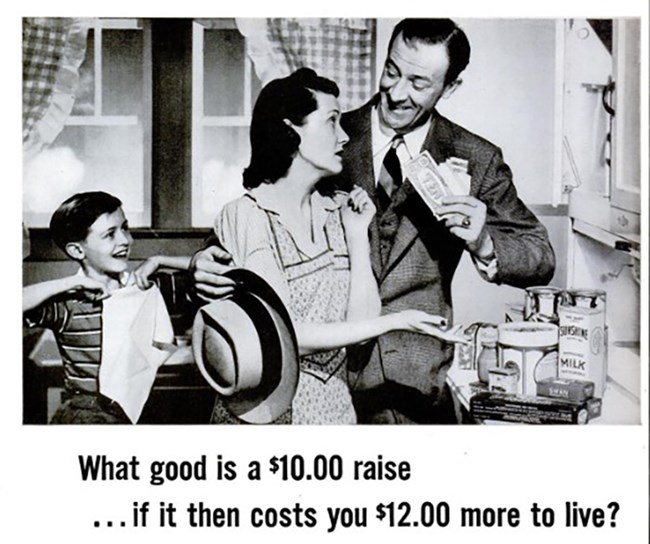

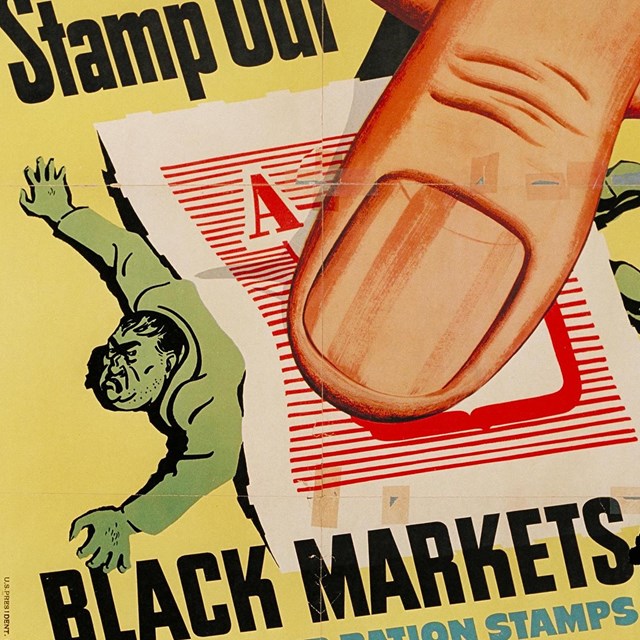

Americans during World War II had money, and they wanted to spend it. And yet, there was a general shortage of goods and materials, and – in areas with wartime employment – a lack of enough housing. The mismatch between supply and demand brought with it the real risk of runaway inflation. With the excesses of the Roaring 20s and resulting Great Depression still fresh in their minds, the government took strong measures to control the economy. One method was by limiting access to goods in short supply accompanied by price controls. These ensured that most Americans could access and afford these goods. Teams of investigators policed the rationing system, exposing and charging those who chose to operate outside it.The government also limited how much money was in circulation. If people had less ready cash, they were less able to drive up prices. The Victory Bonds program and an expansion of income taxes were the primary methods the government used to decrease the amount of money in circulation. Branded as ways to fund the war and bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars, the primary function of these programs was to control the economy. The government’s efforts were largely successful, and inflation was kept to a manageable 4% during the war years.[43]

Even with hundreds of thousands of service members returning and the closure of defense factories, the American economy continued to prosper – fueled, in part, by pent up demand for goods.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] Kennedy 1999: 644.

[3] Kennedy 1999: 644-646; Witkowski and Hogan 1999.

[4] Library of Congress n.d.; Margasak 2016; Musser 2007; Weber and Handley 2016. World War II newsreels and government films are available as part of the Reel America archive at C-Span.

[5] Atkins and Handley 2016a, 2016b; Kugel 2009; Margasak 2016; Mintz and McNeil 2018; Sacks 2018; Zebrowski 2006a.

[6] Guise 2019, 2022; Kugel 2009; Martin 2018; Mintz and McNeil 2018.

[7] Perrone and Handley 2015.

[8] Snider 1995: 5.

[9] The size and appearance of service flags was formalized by the War Department during World War II. Service flags are still in use. They are also referenced in the names of non-profits chartered by Congress, including American Gold Star Mothers (founded in 1928) and Blue Star Mothers of America (founded in 1942) (National Museum of the United States Air Force n.d.).

[10] Kennedy 1999: 637; Zebrowski 2006c. Driving personal vehicles and gasoline were limited to save rubber; availability of civilian rail and bus transportation was limited by the priority for troops and military shipments.

[11] Conn 1959; Southern Labor Archives 2019; US-Japan Conference on Cultural and Educational Interchange 2003. Farmers who stayed on their farms also earned more money than in previous decades providing national and Allied markets. With the extra income, farmers were able to improve their homes including installing indoor plumbing, electric stoves, and hot water heaters (Kennedy 1999: 644-646).

[12] See, for example, Walter P. Reuther Library n.d. a.

[13] Litoff and Smith 1993; Moskowitz 2017.

[14] Litoff and Smith 1993; Moskowitz 2017. Those not staying in a camp took a bus or were picked up.

[15] Connolly n.d.; Litoff and Smith 1993. The Women’s Land Army of America was a similar program during World War I.

[16] Litoff and Smith 1993; Moskowitz 2017.

[17] Litoff and Smith 1993. Other workers were brought in from the Bahamas, Jamaica, Barbados, Newfoundland, and Canada. Under a separate agreement, American railroad companies also brought Mexicans into the US to offset a labor shortage in that sector (Garcia 2023).

[18] Garcia 2023.

[19] Garcia 2023; Martin 2020; National Museum of American History 2017a.

[20] Garcia 2023; National Museum of American History 2017b, 2017c.

[21] Garcia 2023; National Park Service 2022a.

[22] Women were paid less than men had been, and servicemen were required to send only $22 a month home. Harper 2007: 61; Kennedy 1999: 651, 637; National Archives and Records Administration 2016; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. d.

[23] Youth also joined the work force; by 1944, 3 million youth between 14 and 18 years old had gone to work. Younger children aided the war effort by collecting scrap. Harper 2007: 62, 71.

[24] Harper 2007: 62.

[25] Bérubé 1990; Little 2014; National World War II Museum n.d. a; Public Broadcasting Service ca. 2004.

[26] Harper 2007: 71.

[27] Harper 2007: 53, 57.

[28] Pleasant 2020; Walther P. Reuther Library n.d. b.

[29] National Park Service 2022b. Oak Ridge, Tennessee is an American World War II Heritage City. The Manhattan Project National Historical Park is a unit of the National Park Service.

[30] DC also boomed as people moved to the District to work for the federal government. Harper 2007: 52-53.

[31] Harper 2007: 53, 55; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. b; Portland City Club 1945; Reinhardt and Ganzel n.d.

[32] Harper 2007: 53, 55; Reinhardt and Ganzel n.d.; Zebrowski 2006b.

[33] Harper 2007: 53, 55; Reinhardt and Ganzel n.d.

[34] Indiana Memory 1943; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. b; Portland City Club 1945; Reinhardt and Ganzel n.d.

[35] Indiana Memory 1943; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. b; Portland City Club 1945.

[36] 538,000 women volunteered. They served in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAC), the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), the Coast Guard Women’s Reserves (SPARS), Marine Corps Women’s Reserve, Army Nurse Corps, Navy Nurse Corps, and Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP). National World War II Museum n.d. b; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. d.

[37] Harper 2007: 53-54, 55.

[38] Burns and Novick 2007; Burran 1977; Dancis 2018; Detroit Historical Society 2023; Escobedo 2013: 17-22; Harper 2007: 53-55, 125; Kennedy 1999: 651; Lisby 2022; Morenne 2021; O’Neill 1993 :39; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. a; Public Broadcasting Service 2023; Ramírez 2009; Ryon 1993; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum n.d. a, n.d. b; Walter P. Reuther Library n.d. a; Wang 2008a, 2008b; Wills 2021.

[39] Detroit Historical Society 2023; Walter P. Reuther Library n.d. a, n.d b; Wang 2008b.

[40] Harper 2007: 64-66.

[41] Harper 2007: 59.

[42] Harper 2007: 64-66.

[43] In comparison, inflation from 1939 to 1943 was about 24%. Harvey 1944; Oregon Secretary of State n.d. c.

--- (2016b) “Home Front Friday: Wartime War Movies.” See & Hear: Museum Blog, The National WWII Museum, March 4, 2016.

Bérubé, Allan (1990) Coming Out Under Fire. Free Press, New York.

Burns, Ken and Lynn Novick (dir.) “Mobile Shipyards.” The War. Aired on PBS September 22, 2007.

Burran, James A. (1977) “Racial Violence in the South During World War II.” PhD dissertation, Department of History, University of Tennessee.

Conn, Stetson (1959) “Highlights of Mobilization, World War II, 1938-1942.” Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, March 10, 1959.

Connolly, Joyce (n.d.) “’Farmerettes’ Feed a Nation: Serving the Home Front in the Women’s Land Army.” Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.

Dancis, Daniel (2018) “Americans All by Leon Helguera: Appealing to Hispanics on the Home Front in World War II.” The Text Message, National Archives and Records Administration, October 11, 2018.

Detroit Historical Society (2023) “Race Riot of 1943.” Encyclopedia of Detroit.

Escobedo, Elizabeth R. (2013) From Coveralls to Zoot Suits: The Lives of Mexican American Women on World War II Home Front. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Garcia, Jerry (2023) “Bracero Program.” Oregon Encyclopedia: A Project of the Oregon Historical Society, April 7, 2023.

Guise, Kim (2022) “1940s Radio Gold: The Pepsodent Show with Bob Hope.” National World War II Museum, February 10, 2022.

--- (2019) “Two Ambassadors: Bob Hope and Ernie Pyle.” National World War II Museum, January 9, 2019.

Harper, Marilyn (2007) World War II & The American Home Front: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

Indiana Memory (1943) “Demonstration Home 1943.” Pleasant Ridge Government Housing 1942 Photographs, Charlestown, Indiana.

Kennedy, David M. (1999) Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press, New York.

Kugel, Herb (2009) “Hollywood’s Dream Factory During World War II.” Warfare History Network, July 2009.

Library of Congress (n.d.) “Office of War Information.” Research Guides, Rosie the Riveter: Working Women and World War II.

Lisby, Darnell-Jamal (2022) “How the Zoot Suit Got So Much Swag.” American Experience: Zoot Suit Riots: The U.S. Latino Experience, March 2, 2022.

Litoff, Judy Barrett and David C. Smith (1993) “’To the Rescue of the Crops’: The Women’s Land Army During World War II.” Prologue 25(4).

Little, Becky (2014) “Digging Up Ads From WWII – When They Pushed Products No One Could Buy.” National Geographic, December 6, 2014.

Margasak, Larry (2016) “Hollywood Went to War in 1941 – and it Wasn’t Easy.” Oh Say Can You See? Stories from the Museum, May 3, 2016.

Martin, Kali (2018) “Bea Arthur, US Marine.” National World War II Museum, April 12, 2018.

Martin, Philip (2020) “Mexican Braceros and US Farm Workers.” Farm Labor & Rural Migration News Blogs, Wilson Center, July 10, 2020.

Mintz, Steven and Sara McNeil (2018) “World War II: Wartime Hollywood.” Digital History.

Morenne, Benoît (2021) “Were Black GIs Killed in a World War II-Era Race Riot?” Atlas Obscura, July 29, 2021.

Moskowitz, Daniel B. (2017) “The Crop Corps: How Agriculture Helped Win The War.” World War II Magazine, February 20, 2017.

Musser, Rick (2007) “World War II On The Air: Edward R. Murrow And The Broadcasts That Riveted A Nation.” History of American Journalism, December 31, 2007.

National Archives and Records Administration (2016) “Women in the Work Force During World War II.” National Archives and Records Administration: Educator Resources, August 15, 2016.

National Museum of American History (2017a) “Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1943-1964 / Cosecha Amarga Cosecha Dulce: El programa Bracero 1942-1964.” National Museum of American History.

--- (2017b) “Work / Trabajo: Labor and Strife.” Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1943-1964 / Cosecha Amarga Cosecha Dulce: El programa Bracero 1942-1964, National Museum of American History.

--- (2017c) “Work / Trabajo: Broken Promises.” Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1943-1964 / Cosecha Amarga Cosecha Dulce: El programa Bracero 1942-1964, National Museum of American History.

National Museum of the United States Air Force (n.d.) “Service Flags and Pins.” National Museum of the United States Air Force.

National Park Service (2022a) “A New Era of Farmworker Organizing.” National Park Service, December 19, 2022.

--- (2022b) “African American Hutments.” National Park Service, March 11, 2022.

National World War II Museum (n.d. a) “Gender on the Home Front.” National World War II Museum.

--- (n.d. b) “Research Starters: US Military by the Numbers.” National World War II Museum.

O’Neill, William L. (1993) A Democracy at War: America’s Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Oregon Secretary of State (n.d. a) “A Matter of Color: African Americans Face Discrimination.” Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

--- (n.d. b) “A Place of Their Own: Civilian Housing and Rent Control.” Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

--- (n.d. c) “Holding the Line on Inflation: Price Controls Fight the Rise.” Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

--- (n.d. d) “Sending Them Off to War: Pre-Induction Information Programs.” Life on the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II.

Perrone, Catherine and Lauren Handley (2015) “Home Front Friday: Cuba Libre.” See & Hear: Museum Blog, National WWII Museum, September 18, 2015.

Pleasant, Keri (2020) “Honoring Black History World War II Service to the Nation.” U.S. Army, February 27, 2020.

Portland City Club (1945) “Housing.” Portland City Club Report, Collection of the Oregon State Archives, Governor Snell Records, Folder 3, Box 3. From the Life on the Home Front exhibit.

Public Broadcasting Service (2023) “Zoot Suit Riots: Los Angeles Erupts in Violence.” American Experience, The U.S. Latino Experience.

--- (ca. 2004) “Women and Work After World War II.” American Experience, Tupperware!

Ramírez, Catherine S. (2009) The Woman in the Zoot Suit: Gender, Nationalism, and the Cultural Politics of Memory. Duke University Press, Durham, North Carolina.

Reinhardt, Claudia and Bill Ganzel (n.d.) “Strains on Rural Housing” (archived). Farming in the 1940s, Wessels Living History Farm, York, Nebraska.

Ryon, Roderick N. (1993) “When Baltimore’s War Effort Tripped Over Race.” Baltimore Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), August 11, 1993.

Sacks, Ethan (2018) “Captain America: Still Fighting Nazis, Decades Later.” US Holocaust Museum, June 28, 2018.

Snider, Nick (1995) Sweetheart Jewelry and Collectibles. Shiffer, Atglen, Pennsylvania.

Southern Labor Archives (2019) “Southern Labor Archives: Work n’ Progress – Lessons and Stories: Part IV: Labor, the Depression, the New Deal, and WWII.” Southern Labor Archives, Georgia State University Library, May 20, 2019.

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (n.d. a) “Black Americans and World War II.” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Americans and the Holocaust.

--- (n.d. b) “Langston Hughes: ‘Beaumont to Detroit: 1943.’” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum: Black Americans and World War II.

US-Japan Conference on Cultural and Educational Interchange (2003) “US Labor Unions in the 1940s.” Cross Currents.

Walter P. Reuther Library (n.d. a) “Special Focus: 1943 Race Riot.” 12th Street Detroit, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

--- (n.d. b) “Special Focus: Sojourner Truth Housing Project.” 12th Street Detroit, Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University.

Wang, Tabitha (2008a) “Beaumont Race Riot, 1943.” BlackPast, July 3, 2008.

--- (2008b) “Detroit Race Riot (1943).” BlackPast, July 3, 2008.

Weber, Camille and Lauren Handley (2016) “Home Front Friday: Artists for Victory.” See & Hear: Museum Blog, The National WWII Museum, October 28, 2016.

Wills, Matthew (2021) “The Zoot Suit Riots Were Race Riots.” JStor Daily, October 13, 2021.

Witkowski, Terrence H. and Ellen M. Hogan (1999) “Home Front Consumers: An Oral History of California Women During World War II.” Marketing History: The Total Package, Volume 9, pp. 151- 164. Proceedings of the Conference on Historical Analysis and Research in Marketing.

Zebrowski, Carl (2006a) “Fun at the Pictures.” America in WWII, April 2006.

--- (2006b) “Home Sweet Hovel.” America in WWII, October 2006.

--- (2006c) “Staying on Track.” America in WWII, August 2006.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home Front

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home FrontPaper money and coins saw changes because of the war. New materials and new types of money reminded people every day that the US was at war.

-

The Home Front During World War IIServel Co. & History of Refrigeration

The Home Front During World War IIServel Co. & History of RefrigerationDuring World War II, Servel switched from civilian goods to full-scale war production. And they worked to stay relevant with consumers.

-

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black Markets

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black MarketsDespite rationing and other limits on goods during the war, some people figured out how to profit and get what they wanted outside the law.

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- world war ii home front

- homefront

- entertainment history

- economic history

- popular culture

- history of communications

- labor history

- military history

- agricultural history

- government history

- african american history

- latino american history

- asian american and pacific islander history

- women's history

- us in the world community

- migration and immigration

- tennessee

- oak ridge

- washington dc

- awwiihc

- american world war ii heritage city

- michigan

- pennsylvania

- california

- alabama

- indiana

- louisiana

- maryland

- massachusetts

- mississippi

- missouri

- new jersey

- new york

- texas

- manhattan project

- nebraska

- oklahoma

- great migration

- mexico

- prisoners of war

- pow