Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

Note: This historic source uses discriminatory language that is now considered offensive among descendants and the community.

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 533936).

Even before the US formally entered World War II, there was a demand for materials to supply the Allies. But there was greater demand on the part of American manufacturers to supply products for civilians. A report examining American preparation for war noted that, in 1941, US factories made more articles for civilian use than ever before. In response, the US government ordered production cuts to strip off some of this “fat.” They targeted items like cars, lawn mowers, juke boxes, “fancy galoshes,” and other items. With these limits imposed, the government estimated that $20 billion in capacity could be used for military production.[1]

After Pearl Harbor and the other home front attacks of December 1941, the US officially joined World War II. Through patriotism and government mandates, war production boomed across the country. With the boom came an enormous demand for raw materials including things like steel, leather, fabrics, wood, aluminum, and rubber. Many items made from these materials -- including metal toys, cutlery, radios, refrigerators, and washing machines – disappeared from the marketplace. Their materials and manufacturing capacity instead went to the war production.[2] March 31, 1942 was the last day that manufacturers could use tin, steel, copper, aluminum, nickel, chrome, or various other materials for non-military goods.[3]

Some items, like coffee, sugar, rubber, and tin were in short supply because of the war itself. Shipments of coffee from Central and South America were cut off, both by enemy submarine attacks and the need for cargo vessels to carry military instead of civilian goods. [4] These factors also affected the availability of sugar, but even more so was the loss of access to the Philippine sugar industry when Japan captured the islands. [5] At about the same time, Japan attacked and occupied several territories in Southeast Asia. This put them (by design) in control of about 70% of the world’s tin supply and 90% of the world’s supply of rubber just as the US entered World War II. [6] While some rubber was available from South America, ships were unavailable to transport it. [7]

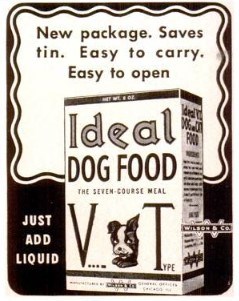

From Life Magazine, July 6, 1942, p. 82.

Some businesses were able to adapt to these restrictions. For example, canned dog food was not seen as a good use of tin. Without access to cans, several companies switched to dehydrated dog food. It came in a box or cardboard “can,” and was rehydrated with water or milk before serving.[8]

Companies shifted their packaging to jars and boxes; aluminum pots and pans were replaced by enamelware; and toys were made from wood and cardboard by factories and by families at home; and the Girl Scouts sold calendars instead of cookies.[9] Government limits on the use of fabrics for civilians also changed how people dressed. Gone were double-breasted suits, vests, cuffs on pants, patch pockets, pleated skirts, long hemlines, and one-piece bathing suits. [10] Faced with a fabric shortage, people mended their clothing, sewed their own using feed sacks, and knitted. When nylon and silk vanished from the market, women adapted by drawing stocking seams on their legs. These were known as “bottled stockings.” [11]

Even in wartime, however, businesses and civilians still needed access to products like shoes, foods, gasoline, and heating fuel. The ration system helped manage this problem.

Posters Encouraged Different Types of Rationing

Left image

“Use it Up – Wear it Out – Make it Do! Our labor and our goods are fighting.” poster encouraging people to use what they have to support the war effort. Office of War Information 1943.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513834).

Right image

“Americans! Share The Meat as a wartime necessity.” Poster urging people to voluntarily limit how much meat they buy to between 3/4 pound per week for children under 6 to 2-1/2 pounds per week for people over 12. Office of War Information, 1942.

Credit: Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513804).

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017850484).

Rationing

In World War I and before the US entered World War II, the government asked people to ration voluntarily.[12] This approach was unsuccessful. Instead, people hoarded products and costs rose, and those without money simply went without needed goods.

In January 1942, just a few weeks after the Japanese attacks in the Pacific, the federal government mandated rationing. This limited the availability of certain goods and materials and ensured fair distribution, given the needs of the war. Establishing maximum or ceiling prices for rationed goods also helped to keep inflation in check. Using their nation-wide overview of supply, demand, and the economy, the federal government dictated which items to ration, set ceiling prices, and allocated available supply. Rationing was overseen by the federal Office of Price Administration (OPA) in conjunction with other war offices, including the Wartime Production Board (WPB). It was managed at the local level by volunteer rationing boards. At their local rationing offices, people registered for and received their ration books, and could apply for ration certificates or additional coupons. When the war ended, over 100,000 citizen volunteers were managing the program organized into about 5,600 local boards.[13]

![A pin worn by local rationing board volunteers. To save metals for the war, it is made of plastic. Photo by Megan E. Springate. Collection of the author. A shield-shaped white plastic pin printed in blue and red. In blue: “OPA [image of a scale] VOLUNTEER.” In red: “WAR PRICE AND RATIONING BOARD.” Collection of the author.](/articles/000/images/Ration-Image-6-OPA-Volunteer-Board-Member-Pin-Resize400.jpg?maxwidth=650&autorotate=false)

Photo by Megan E. Springate. Collection of the author.

The ration program had four systems:

- certificate rationing (for items like tires, cars, and stoves that required applying for a certificate to buy);

- differential coupon rationing (for things like gasoline and heating oil that some people needed more than others);

- uniform coupon rationing (for things like shoes, sugar, and coffee rationed at fairly stable amounts per person); and

- point rationing (for items like meats and canned goods where supply and demand varied greatly).[14]

In each of these four systems, to buy something, shoppers had to produce the right ration coupons, stamps, certificates, or points plus the cost of the item. To control the rate of spending and discourage hoarding, coupons and stamps expired at set times. [15] The OPA added and removed items from the ration list throughout the war. Rationing ended as goods became available. By the end of 1945, the only thing still rationed was sugar. It remained under ration until June 1947. [16]

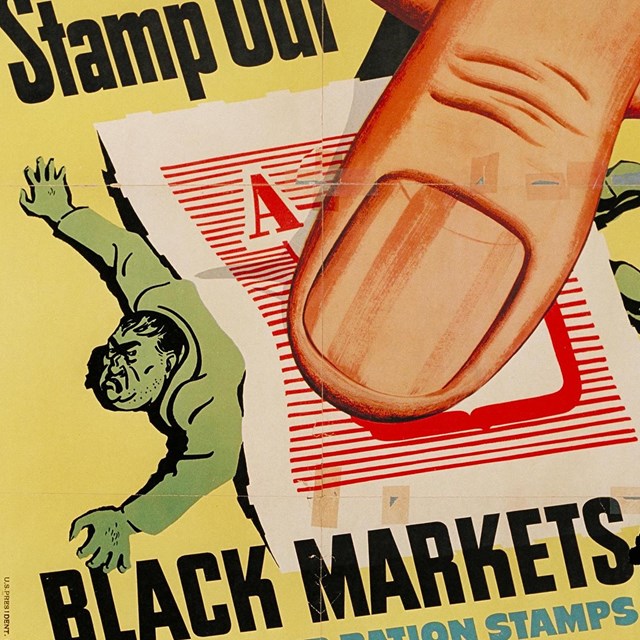

Despite the best efforts of the government, the volunteer rationing boards, the police, and civilian defense workers, there were many people who found ways to work around the ration system. These included theft, counterfeiting, hoarding, fraud, and organized crime in illicit trade, also called the black market.

Read more about food rationing and rationing of non-food items.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] United States Office of Facts and Figures 1942: 46.

[2] Aluminum Goods Manufacturing Company 1941; Kennett 1985: 118, 124, 126-127; Winner-Swete 2013.

[3] New York Times 1942.

[4] Sundin 2022a.

[5] Hayes 2000: 77.

[6] Chen 2010; Mitter n.d.; Provost 2022: 104-105; Sundin 2023.

[7] Sundin 2022b.

[8] Kennett 1985: 129-139.

[9] Lakeside Packing Company ca. 1947; United States Department of Labor 1942; United States Office of Facts and Figures 1942: 45; Winner-Swete 2013; Wright Museum of World War II 2020.

[10] Kennedy 1999: 644; Life Magazine 1942: 70-71. What we know now as the bikini (named for Bikini Atoll, where atomic testing took place) was not invented until 1946 in France. It shocked the world by revealing a woman’s belly button (Hendrix 2018).

[11] Kennett 1985: 138; Moore Memorial Public Library n.d.; National Park Service 2016; Perrone and Handley 2016; Turner 2022.

[12] Hayes 2000:4.

[13] National World War II Museum n.d.

[14] Ames History Museum n.d.; Hayes 2000: 4.

[15] Lee 2021; National World War II Museum n.d.

[16] Ames History Museum n.d.; National World War II Museum n.d.

Aluminum Goods Manufacturing Company (1941) “Aluminum Toys. Catalog no. 123.” Aluminum Goods Manufacturing Company, Manitowoc, Wisconsin. Collection of the Manitowoc County Historical Society.

Ames History Museum (n.d.) “World War II Rationing on the U.S. Homefront.” Ames History Museum.

Chen, C. Peter (2010) “Invasion of Malaya and Singapore 8 Dec 1941 – 15 Feb 1942.” World War II Database, March 2010.

Hayes, Joanne L. (2000) Grandma’s Wartime Kitchen: World War II and The Way We Cooked. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Hendrix, Steve (2018) “A Scandalous, Two-Piece History of the Bikini .” The Washington Post, July 7, 2018.

Kennedy, David M. (1999) Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press, New York.

Kennett, Lee (1985) For the Duration... : The United States Goes to War, Pearl Harbor-1942. Scribner, New York.

Lakeside Packing Company (ca. 1947) “Lakeside Vegetables in Glass Jars.” Collection of Manitowoc Public Library.

Lee, Karen (2021) “Coupons and Canned Corn: What a WWII Shopping List Reveals about Rationing.” Fishwrap: Official Blog of Newspapers.com, August 21, 2021.

Life Magazine (1942) “Women Lose Pockets and Frills to Save Fabrics.” Life Magazine, April 20, 1942, p. 70-71.

Mitter, Rana (n.d.) “Liberation in China and the Pacific.” National World War II Museum.

Moore Memorial Public Library (n.d.) “Making Do: Rationing.” Moore Memorial Public Library.

National Park Service (2016) “Sacrificing for the Common Good: Rationing in WWII.” National Park Service, June 3, 2016.

National World War II Museum (n.d.) “Rationing.” National World War II Museum.

New York Times (1942) “Small Appliances to Halt on May 31.” New York Times, March 31, 1942, p. 33.

Perrone, Catherine and Lauren Handley (2016) “Home Front Friday: Sew It Up.” See & Hear: Museum Blog, National WWII Museum, January 8, 2016.

Provost, Nyla (2022) “The Development of Synthetic Rubber and its Significance in World War II.” History in the Making 15: 103-125.

Sundin, Sarah (2023) “Make It Do: Rationing of Canned Goods in World War II.” Today in World War II History, February 27, 2023.

--- (2022a) “Make It Do: Coffee Rationing in World War II.” Today in World War II History, November 21, 2022.

--- (2022b) “Make It Do: Tire Rationing in World War II.” Today in World War II History, January 5, 2022.

Turner, Nan (2022) Clothing Goes to War: Creativity Inspired by Scarcity in World War II. Intellect, Chicago.

United States Department of Labor (1942) “Toys in Wartime: Suggestions to Parents on Making Toys in Wartime.” United States Department of Labor, Children’s Bureau, Washington, DC.

United States Office of Facts and Figures (1942) “Report to the Nation: The American Preparation for War.” United States Office of Facts and Figures, January 1942.

Winner-Swete, Tara (2013) “The Home Front: Toy Production During World War II.” The Strong National Museum of Play, June 11, 2013.

Wright Museum of World War II (2020) “Toys in Wartime: How Parents Provided Homemade Toys for Their Children During WWII.” Wright Museum of World War II, May 11, 2020.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IICoffee Rationing

The Home Front During World War IICoffee RationingCoffee was rationed from November 1942 to July 1943. Each person got enough coffee to average less than one cup a day.

-

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food Items

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food ItemsRationed items included tires, cars, bicycles, gasoline, home heating fuels, shoes, stoves, footwear, and typewriters.

-

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black Markets

The Home Front During World War IIIllicit Trade and Black MarketsDespite rationing and other limits on goods during the war, some people figured out how to profit and get what they wanted outside the law.

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- developing the american economy

- shaping the political landscape

- home front

- home front.

- rationing

- wwii home front

- wwii homefront

- world war ii home front

- industrial history

- clothing

- business history

- military history

- international relations

- japan

- philippines

- fashion history

- economic history

- american world war ii heritage city program

- american world war ii heritage city

- awwiihc

- government history

- new orleans

- louisiana