Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Currency on the World War II Home Front

Money in the Continental United States

Collection of the National Museum of American History, National Numismatic Collection.

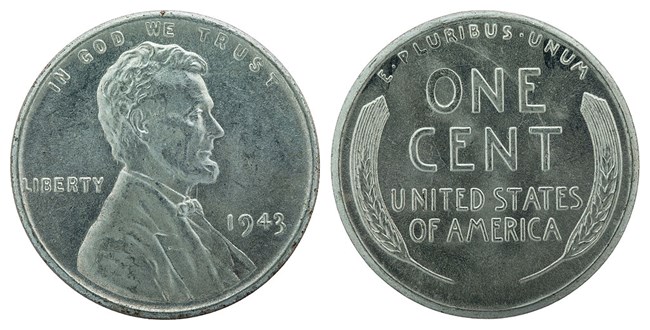

When the United States officially entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and other home front areas part of the Greater United States, wartime production increased dramatically. And so did the need for certain strategic materials. Among these were copper, tin, zinc, and nickel. Pennies at the time were made of 95% copper, 4% zinc, and 1% tin, and the government looked for an alternative. They tried glass and plastic replacements, but finally decided on a low-grade steel coin covered with a thin coating of zinc to prevent rust.[1] Nearly 1.1 billion 1943 steel cents were minted in Philadelphia, Denver, and San Francisco. This saved more than 40,000 pounds of tin and enough copper to manufacture 1.25 million artillery shells.[2]

The public did not like the “steelies.” They didn’t like that they weren’t copper-colored. They didn’t like that they didn’t work in vending machines. They didn’t like when they mistook them for dimes. And they didn’t like when the zinc oxidized and turned black or wore off and the steel rusted.[3] From 1944 to 1946, the US Mint replaced the steelies with pennies that used brass salvaged from spent shell casings as a source of copper and zinc.[4]

Collections of Hawai'i State Archives, Photograph Collection, PPWD-18-2-013.

American nickels also saw a wartime change. In spring 1942, Congress ordered the US Mint to remove all nickel from the five cent coin (originally 75% copper and 25% nickel). Nickel was used to harden steel for uses like tank armor and anti-aircraft guns. The Mint produced wartime nickels made from 56% copper, 35% silver, and 9% manganese from 1942 to 1945.[5] Unlike the steelies, these nickels didn’t look much different from their pre-war incarnations. Overall, this change saved the US government about 800,000 pounds of nickel and 1.8 million pounds of copper for the war effort.[6]

Money in Hawai’i.

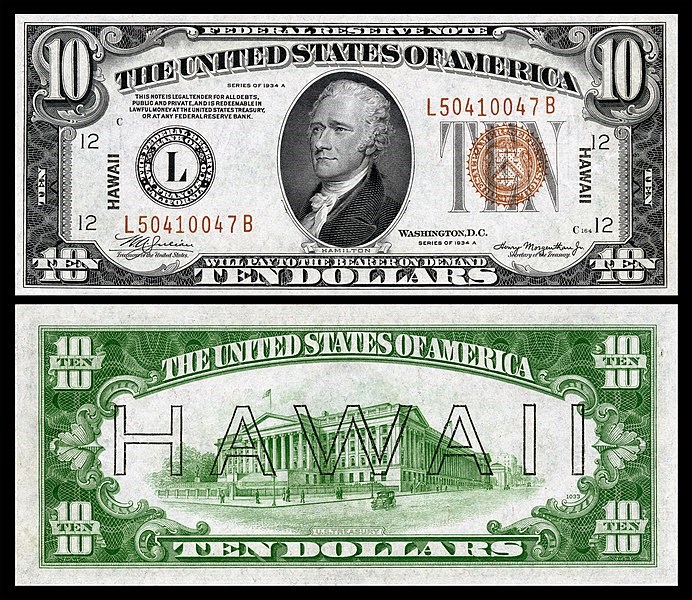

Even though the US repelled Japanese forces when they attacked Pearl Harbor, the US government was afraid that they might come back and capture Hawai'i. This would be a problem not just for the people of the islands and the US military, but also the US economy. The money used in Hawai'i was American currency. If Japan captured the islands, they would also capture the American cash circulating there. To lose that much currency and to have it in the hands of their enemy could cause havoc.[7]To solve the problem, in January 1942, the US government pulled all American money out of circulation in Hawai'i (except for $200 per person and $500 per business). To dispose of the $200 million collected, they government took it to the Nu’uanu Mortuary for burning. The crematorium couldn’t handle that much paper at once. It was finally destroyed in the furnaces at the boiler house of the Honolulu Sugar Company (also known as ‘Aiea Sugar Plantation). The smoke from the burning bills would have been visible from the Naval base just across Pearl Harbor.[8]

The government then issued money printed just for use on the islands. They were the same as US currency, but had “HAWAII” printed on both sides of the bill. If Japan took Hawai'i, these bills could be declared useless.[9] These were the only legal paper money on the islands from August 1942 until October 1944. There are stories of people who kept large amounts of this currency hidden in their homes “just in case.” The good news is that it is still legal tender, and worth its face value (though bills in really good condition are often worth more to collectors).[10]

Collection of the National Numismatic Collection, National Museum of American History. CC BY-SA 4.0.

Money in the Philippines

Megan E. Springate. Collection of the Author.

Before World War II, the Philippines issued their own paper money and coins as a commonwealth of the United States. Some of it came from the mainland, with coins from the San Francisco and Philadelphia Mints and bills printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing in DC. Some of the coins were minted at the Manila Mint, also known as Casa de Moneda, the “House of Money.” It was the only US Mint located outside the continental United States. It ceased production in World War II, and was destroyed when Allied forces retook the Philippines in 1945.[11]

As the Japanese occupation of the Philippines spread across the islands in 1941 and 1942, the government emptied the treasury to prevent it from falling into enemy hands. They were able to ship some of it (two tons of gold bullion and 18 tons of silver pesos) to Australia, and hid the rest. When it became clear that Japan was going to take the country, the Filipino government destroyed the hidden riches, burning paper money and government securities. The remaining 390 tons of silver pesos were dropped in the dead of night into a deep and choppy area of Caballo Bay.[12]

It did not take long for the occupying Japanese to find out, and they sent Filipino divers to recover the coins. Several of these divers died from the bends after surfacing too quickly, and the rest refused to continue diving.[13] The Japanese turned to imprisoned US Navy men to replace the Filipinos. They purposefully sabotaged the mission, working very slowly and sometimes pocketing coins. They also insisted on short dives and safety stops so they would not get the bends. By the time the Japanese stopped trying to gather the coins, they had recovered about one-eighth of the treasure which they melted down and shipped back to Japan.[14]

Collection of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1992.23.1623C.

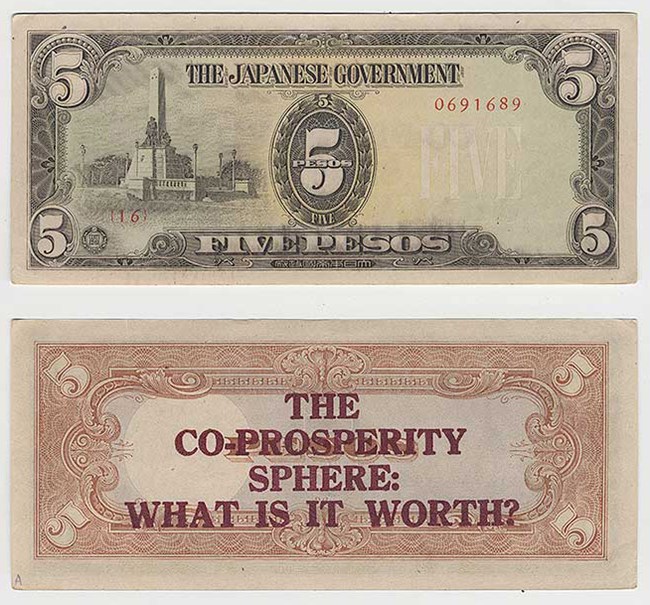

The occupying Japanese brought their own currency to the Philippines. Known as Japanese Invasion Notes, Japanese Occupation Money, and “Mickey Mouse Money” by the locals, it became the only legal currency.[15] Bills in the Philippines were in pesos and centavos and have “The Japanese Government” printed on them.[16]

Collection of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1992.23.1663.

Collection of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, 1992.23.1635A.

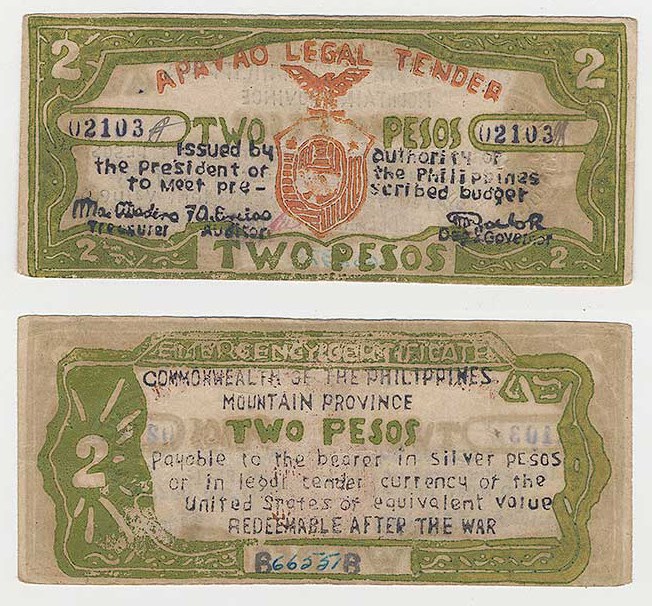

Those Filipinos working against the Japanese occupiers needed a way to pay for supplies and food. No one could afford to give supplies away, even if they opposed the Japanese occupation. In response, the Philippine government in exile as well as regional groups and banks printed Emergency Notes (also called guerilla currency or Emergency Circulating Notes) for local use. Forced to use what was available, designs are often crudely stamped on poor quality paper. Those who refused to accept these emergency notes were often perceived as siding with the Japanese. At the same time, those found to have them (and their families) were arrested and often executed.[17]

It took from October 1944 through August 1945 for Allied forces, led by US General Douglas MacArthur, to retake the Philippines.[18] As Allied forces advanced, they began parachuting in large quantities of counterfeit Japanese Invasion Notes. Dropped where guerillas could find them, these were very good counterfeits printed in the US and Australia. They were designed to be spent, making the real versions less valuable. At the same time, Allied forces were overprinting captured Japanese Invasion Notes with “The Co-Prosperity Sphere: What Is It Worth?” The Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was the goal of the Japanese Empire: to liberate East Asia from white colonial rule, uniting it for the prosperity of all under the guardianship of Japan. Allies dropped these propaganda notes over the Philippines, encouraging Filipinos who had been suffering under Japanese occupation to oppose it, and to demoralize the Japanese.[19]

Image by Jscandila, public domain (Wikimedia).

Money in Guam

Photo by Megan E. Springate. Collection of the Author.

Money in Assembly, Incarceration, and Prisoner of War Camps

The systems of currency varied between those considered enemy aliens, Prisoners of War, and those of Japanese descent and their families incarcerated in War Relocation Authority centers. While enemy alien detention centers and Prisoner of War camps relied on scrip for all transactions within them, those incarcerated by the War Relocation Authority dealt with a much more complex system.War Relocation Assembly and Incarceration Centers

The economies in the War Relocation Authority (WRA) centers and assembly centers ran on a complex and seemingly ever-changing system of US cash, checks, and money orders as well as chits (also called scrip or coupons). When the forced relocation was announced, some were able to sell or rent their assets, and to put those funds into their bank accounts. But not everyone had free access to their pre-war money in the assembly centers and camps for things like supplemental food, mail order goods, and toiletries, or to pay their income and property taxes.[26]

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 538244).

Those of Japanese ancestry who were not US citizens (largely first generation Issei) or who banked with a Japanese-owned bank (based either in the US or in Japan) were suspect, and had their accounts blocked or frozen by the US government.[27] When Japanese-owned US banks failed (unsurprising when they were not allowed to operate), their assets were liquidated and clients had the opportunity to file claims for their assets.[28]

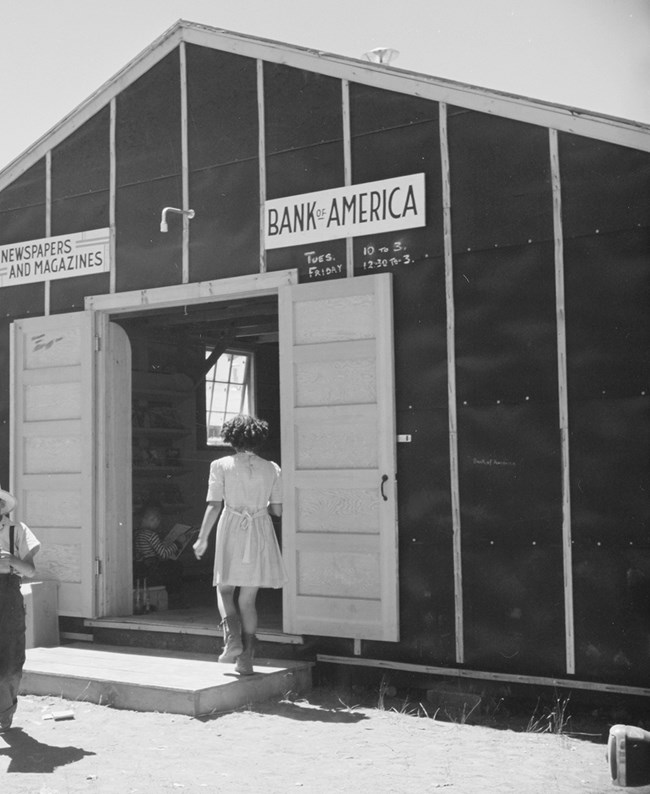

Camp residents were paid their allowances and employment income by cash, check, and (less frequently) scrip. Co-ops, offering goods and services and run by camp residents, operated using scrip or cash – and sometimes both.[29] Banking services were available through camp-run banking systems, offices visited by bankers from outside banks, and by the co-ops. Those whose pre-war accounts were not frozen could also transfer money in and out of the camp. Which of these services were available at any given time depended on WRA and center policies, staffing, and other factors.[30] For example, when the Bank of America branch at Tule Lake closed because the bank employee managing it was transferred to a different bank branch, the Co-Op was available to cash checks (but only government and traveler’s checks).[31]

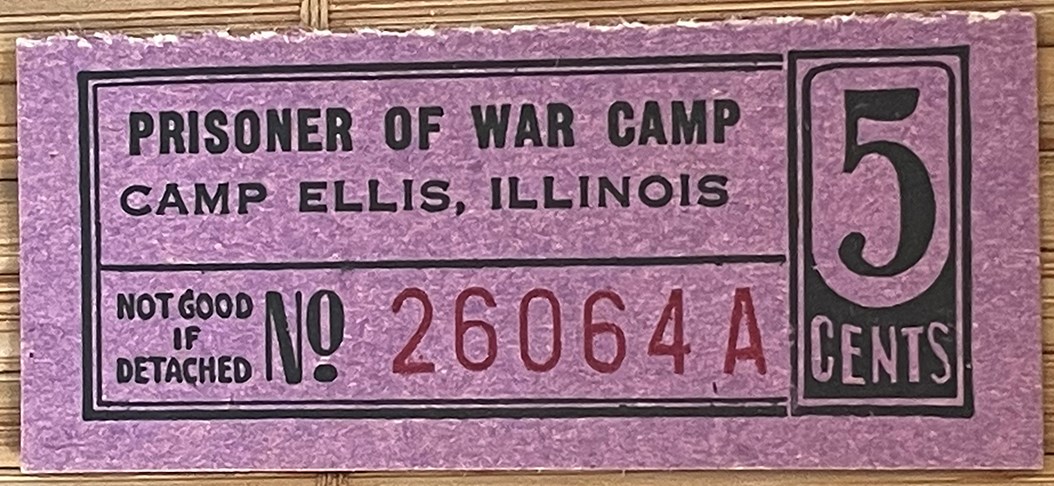

Prisoner of War Camps

All Prisoners of War held in the United States were paid a monthly allowance by the US government into a Treasury account. For enlisted prisoners, this was $3; officers received more (lieutenants $20; captains $30; majors and above $40; Japanese officers received $5 per month less until late in the war). Those POWs (including officers) who chose to work were paid an additional 80 cents per day, roughly equivalent of the 1941 pay of a US private.[32]

Prisoners of War could request to receive some of their pay in camp money called coupons, chits, or scrip. These could then be used within the camp as money. Prisoners were not issued actual US currency in case of escape.[33] Each camp had its own chits. Like point rationing coupons, chits were issued in serial-numbered booklets, often valid only for a period of time, and only the shop clerk was permitted to remove chits to pay for items.[34] Where these chits could be used was printed on them: “Prisoner of War Canteen” or “Prisoner of War Camp Post Exchange.”[35] Items available included toiletries, stationery and postage, tobacco and cigarettes, low alcohol beer (3.2% alcohol), candy, and soft drinks. When POWs were repatriated, they received a check for all the money left in their Treasury accounts plus whatever remaining chits they turned in.[36]

Former Italian POWs who transferred to Italian Service Units after the surrender of Italy in 1943 and those held in alien detention camps -- enemy aliens of Japanese, German, and Italian nationality or ancestry – also used camp-issued scrip. Most used paper chits similar to those used in POW camps (with the difference that they were printed “Internment Camp Canteen”/ “Internment Camp Post Exchange” or “Italian Service Branch.”[37] At least two alien detention camps in Texas, Crystal City and Seagoville, used tokens instead. These were non-metallic tokens made of pressed paper and plastic.[38]

Special Mention

There are two other examples of US money that are related to World War II: the Roosevelt dime (ten cent piece) and the Mary Golda Ross one dollar coin.

United States Mint, 2005.

Roosevelt Dime

President Roosevelt, who had carried the United States through the Great Depression and most of World War II, died in April 1945. With popular support, the dime was redesigned with his face on one side and torches on the other. Sculptor Selma Burke, an African American woman, created the bas relief sculpture of FDR that was adapted for use on the dime. In the 1920s, she was part of the Harlem Renaissance. During the Great Depression, she taught art to youth in New York City with the Works Progress Administration. She was also one of the first African American women to enlist in the Navy during World War II. She drove a truck at the Brooklyn Navy Yard until she was injured. It was while recuperating that she sculpted the image of President Roosevelt. In order to assure a proper likeness, she asked for (and received) permission to sketch the president in person at the White House. She completed the sculpture in 1944.[39]

The Roosevelt dime went into circulation for 1946, and is the design we still use today. The 10 cent denomination was chosen because of President Roosevelt’s close association with the organization, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis. FDR founded the organization in 1938 to combat polio – a disease he had been diagnosed with in 1921. Their first annual fundraising drive, called the March of Dimes, brought in donations of over 2.6 million dimes. The organization was later renamed the March of Dimes Foundation.[40]

Courtesy the United States Mint.

Mary Golda Ross One Dollar Coin

The second is the US 2019 one dollar coin featuring Mary Golda Ross. Ross was the first Native American woman engineer. Her great-great-grandfather was Cherokee Chief John Ross. She received her Master’s degree in mathematics in 1938. In 1942, Mary Ross was hired by Lockheed’s Advanced Development Projects (colloquially known as the Skunk Works). Her job was to rescue the P-38 Lightning aircraft project.Rushed into production for the war, the plane was unstable as it reached the speed of sound, and pilots died. Mary Ross was on a team of “computers” -- women who did the calculations needed for research. The team of women for the P-38 Lightning successfully calculated changes to the plane’s design to make it stable. After the war, when many women lost their jobs, Ross stayed at Lockheed. She later worked on early space projects.[41]

Photo by Megan E. Springate. Collection of the author.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Bamford 2020; Sieber 2013: 56.

[2] Bamford 2020. The United States Mint in Denver at West Colfax Avenue and Delaware Street, Denver, Colorado was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on February 1, 1972. The United States Mint in San Francisco at 155 Hermann Street, San Francisco, California was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on February 19, 1988.

[3] Bamford 2020; ModernCoinMart 2018.

[4] Bamford 2020; Coin Keeper 2021; Herbert 2008.

[5] Coin Keeper 2021; Sieber 2013: 97.

[6] Bamford 2020.

[7] Bamford 2020.

[8] Metz 1995; Morton 2015; Young 2022. The ‘Aiea Sugar Mill was placed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 11, 1996. It was delisted in 2009 after it was demolished.

[9] Bamford 2020; Bureau of Engraving and Printing 2013.

[10] Bamford 2020; Krauss 2005; Morton 2015; Sieber 2013: 477.

[11] Oobie 2020. For a discussion on the tensions between Filipino and American imagery on the money, see Akiboh 2017.

[12] Malinowski 2014.

[13] The bends, also known as decompression sickness, happens when divers come up quickly from deep water. Gasses that dissolved into the body under pressure turn into bubbles as the pressure decreases. This is similar to when you open a bottle of soda – the release of pressure causes bubbles to form. The faster a diver surfaces and the deeper they have been make the condition worse, and even deadly. Malinowski 2014.

[14] After World War II, more than 8.8 million pesos were recovered by government crews. Some people suggest that there are more still to be recovered. Malinowski 2014; Numismatic Guarantee Company (NGC) Collectors Society (n.d.).

[15] Japan wanted to replace all traces of Western influence in its captured territories. Australian War Memorial 2023; Keister 2017, 2022.

[16] In general, the Japanese issued their occupation money in the same currencies it was replacing. In Malaya, they were in dollars and cents; in Burma, they were in rupees; in the Dutch East Indies they were in gulden and cents; and in the British Islands of the Southwest Pacific they were in pounds and shillings. Australian War Memorial 2023.

[17] Keister 2017, 2022

[18] Japan surrendered after the US dropped atomic bombs on Nagasaki and Hiroshima.

[19] Stevenson 1992; Swan 1996

[20] Stevenson 1992.

[21] NCG Collectors Society n.d.

[22] Bureau of Engraving and Printing 2013.

[23] Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas 2020; The Paginator 2018.

[24] Patacsil 2023.

[25] Rogers 2011: 158.

[26] Granada Pioneer 1942: 1; Manzanar Free Press 1945a; Okubo et al. 1943: 8.

[27] Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement 1942a; Official Information Bulletin 1942; Washburn 1944. Rumors went around that the government had seized the assets of those involuntarily incarcerated. The government quickly put the rumor to rest, insisting that accounts had not been seized, but “merely controlled through freezing” (Official Information Bulletin 1942). After the war, people could apply for the recovery of their frozen accounts through the Alien Property Office (Northwest Times 1948).

[28] Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement 1945; Manzanar Free Press 1945b.

[29] Daily Tulean Dispatch 1943b.

[30] Fresno Grapevine 1942; Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement 1942b; Daily Tulean Dispatch 1942, 1943a, 1943c; Santa Anita Pacemaker 1942.

[31] Daily Tulean Dispatch 1943b, 1943c.

[32] Work done associated with the management and administration of the camp was largely unpaid, as it was considered for the benefit of the prisoners. The exception was if a prisoner was doing so much unpaid camp work that they were unable to accept paid work. Frank and Seelye 2019: 6-7; Rundell 1958: 121-123.

[33] Rundell 1958: 123.

[34] Frank and Seelye 2019: 7, 31.

[35] Frank and Seelye 2019: 18.

[36] Frank and Seelye 2019: 7.

[37] Several Italian Service Unit chits are not identified directly as such, but do have text in both Italian and English. Frank and Seelye 2019: 204, 2010; Texas Historical Commission 2020.

[38] Brosveen 1995; Frank and Seelye 2019: 204; Russell 2015: 108; Texas Historical Commission 2020. Those incarcerated at the Crystal City Alien Detention Station could work in the camp and earn 10 cents per hour up to $4 per week. This was in addition to their monthly allocation of $4 in tokens for children between 6 and 13 years old; $1.25 in tokens for 2 to 5 year olds; and $5.25 in tokens for adults.

[39] Brandman 2021; Smithsonian American Art Museum n.d. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 22, 2014. One of the several schools Burke taught at was Livingstone College in Salisbury, North Carolina. Livingstone College Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on May 27, 1982. Burke and her husband Herman Kobbe moved to New Hope, Pennsylvania in 1949. He died in 1955, and Burke continued to live in New Hope until her death in 1995. The New Hope Village District was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 6, 1985.

[40] Baghdady and Maddock 2008; United States Mint 2022.

[41] Wallace 2021.

Akiboh, Alvita (2017) “Pocket-Sized Imperialism.” Diplomatic History 41(5): 874-902.

Australian War Memorial (2023) “Japanese Invasion Currency: 1/2 Shilling Note.” Australian War Memorial.

Baghdady, Georgette and Joanne M. Maddock (2008) “Marching to a Different Mission.” Stanford Social Innovation Review 6(2): 61-65.

Bamford, Tyler (2020) “Steel Cents, Silver Nickels, and Invasion Notes: US Money in World War II.” National World War II Museum, December 4, 2020.

Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas (2020) “Coins and Notes – Demonetized Coins and Notes.” Bangko Sentral Ng Pilipinas.

Brandman, Mariana (2021) “Selma Burke.” National Women’s History Museum.

Brosveen, Emily (1995) “World War II Internment Camps.” Texas State Historical Association, November 1, 1995.

Bureau of Engraving and Printing (2013) “BEP History Fact Sheet: Special and Allied Military Currency.” Historical Resource Center, Bureau of Engraving and Printing, April 2013.

Coin Keeper (2021) “US Coins During World War II.” American Numismatic Association, Coin Keeper’s Blog, December 13, 2021.

Daily Tulean Dispatch (1943a) “Co-op Will Issue Money Orders, Travelers’ Checks.” Daily Tulean Dispatch, June 1, 1943, p. 1. Collection of Densho, Tulean Dispatch Collection, courtesy of Joe Matsuzawa.

--- (1943b) “Co-op Will Eliminate Scrip: New Patronage System to Use Cash Register.” Daily Tulean Dispatch, May 11, 1943, p. 1. Collection of Densho, Tulean Dispatch Collection, courtesy of Joe Matsuzawa.

--- (1943c) “Bank of America Service is Discontinued Until Apr. 6.” Daily Tulean Dispatch, March 18, 1943, p. 1. Collection of Densho, Tulean Dispatch Collection, courtesy of Joe Matsuzawa.

--- (1942) “Bank Now Open 3 Days a Week.” Daily Tulean Dispatch, August 10, 1942, p. 3. Collection of Densho, Tulean Dispatch Collection, courtesy of Joe Matsuzawa.

Frank, Dave and David E. Seelye (2019) The Complete Book of World War II USA POW & Internment Camp Chits: Prisoner of War Money in the United States. Coin & Currency Institute, Williston, VT.

Fresno Grapevine (1942) “Bank Service Starts Friday.” Fresno Grapevine (Fresno Assembly Center, CA), June 24, 1942, p. 1. Collection of the Hoover Institution Library.

Grenada Pioneer (1942) “Real Property Taxes Due.” Grenada Pioneer (Amache, CO), November 14, 1942, p. 1. Collection Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement (1945) “Yokohama Bank Seeks Addresses of Claimants.” Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement, Series 301, May 8, 1945. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

--- (1942a) “Clothing Allowances to Be Paid in Cash or Check.” Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement, Series 1, October 27, 1942. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

--- (1942b) “Powell Bank to Cash Checks Today.” Heart Mountain Sentinel Supplement, Series 1, October 27, 1942. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

Herbert, Alan (2008) “Shell Casings Melted by Alloy Unchanged.” Numismatic News, July 21, 2008.

Keister, Jake (2022) “Japanese Government-Issued Philippine Occupation Fiat Bank Note: 5 Pesos.” Spurlock Museum of World Cultures.

--- (2017) “Featured Object: Philippine Emergency Notes.” Spurlock Museum of World Cultures Blog, June 1, 2017.

Krauss, Bob (2005) “Wartime Currency Not So Rare.” Honolulu Advertiser, July 27, 2005.

Malinowski, Jamie (2014) “Silver Salvage in Caballo Bay: Japan’s Sabotaged Treasure Hunt.” Warfare History Network, February 2014.

Manzanar Free Press (1945a) “March 15 Deadline for Filing 1944 Income Tax.” Manzanar Free Press, February 28, 1945, p. 1. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

--- (1945b) “Project Attorney Will Give Aid in Proving Sumitomo Bank Claims.” Manzanar Free Press, January 6, 1945, p.1. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

Metz, Paula W. (1995) “National Register of Historic Places Nomination: Honolulu Plantation Company.” National Archives and Records Administration, July 20, 1995.

ModernCoinMart (2018) “History of the Penny.” ModernCoinMart, July 18, 2018.

Morton, Ella (2015) “Object of Intrigue: Banknotes for a Japanese-Occupied Hawaii.” Atlas Obscura, October 13, 2015.

Northwest Times (1948) “Alien Property Office Gives Further Data on Recovery of Pre-War Bank Deposits.” Northwest Times, January 13, 1948, p. 1. Collection of Densho, Northwest Times Collection, Courtesy of Hideo Hoshide.

Numismatic Guarantee Company (NGC) Collectors Society (n.d.) “USA/Philippines Type Set (Expanded Edition) Five Centavos 1944-1945 Wartime Alloy.” NGC Collectors Society.

Official Information Bulletin (1942) “Federal Reserve Bank Hits Rumors About Asset Seizures: Flat Denial Is Given By Bank to Property Appropriate Talk.” Official Information Bulletin (Poston Relocation Center, AZ), June 10, 1942, p. 1. Collection of the Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

Okubo, Ituge, Tomoo Ogita, Virginia Takemura, Kimiko Naruse, Mary Rikimaru, Yoshie Takayama, Irene Miyamoto, James Makimoto, Mary Suzuki, Maye Oye, and John A. Rademaker (1943) “Granada Community Analysis Report #2.” Community Analysis Section, Granada Relocation Center, Colorado, June 1943. Collections of the California State University, Sacramento, Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

Oobie (2020) “The Manila Mint: Gone, but Mostly Forgotten.” American Numismatic Association, Young Numismatists Exchange, Oobie’s Blog, May 26, 2020.

Patacsil, Peter E. (2023) “Spanish Coinage in Guam.” Guampedia.

Rogers, Robert F. (2011) Destiny’s Landfall: A History of Guam, revised edition. University of Hawai'i Press, Honolulu.

Rundell, Walter Jr. (1958) “Paying the POW in World War II.” Military Affairs 22(3): 121-134.

Russell, Jan Jarboe (2015) The Train to Crystal City: FDR’s Secret Prisoner Exchange Program and America’s Only Family Internment Camp During World War II. Scribner, New York.

Santa Anita Pacemaker (1942) “Santa Anita Bank Hours Announced for Next Week.” Santa Anita Pacemaker (Santa Anita Assembly Center, CA), July 18, 1942, p. 1-2. Collection of the California State University, Department of Special Collections and University Archives.

Sieber, Arlyn G. (2013) Warman’s U.S. Coins & Currency Field Guide, 5th edition. Krause Publications, New York.

Smithsonian American Art Museum (n.d.) “Artist: Selma Burke.” Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Stevenson, Jed (1992) “Coins.” New York Times, February 2, 1992.

Swan, William L. (1996) “Japan’s Intentions for Its Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere as Indicated in Its Policy Plans for Thailand.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 27(1): 139-149.

Texas Historical Commission (2020) “Crystal City (Family) Internment Camp.” Texas Historical Commission, March 13, 2020.

The Paginator (2018) “It’s VICTORY!” American Numismatic Association, The Paginator’s Blog, April 19, 2018.

United States Mint (2022) “Dime.” United States Mint, December 9, 2022.

Wallace, Rob (2021) “Mary Golda Ross and the Skunk Works.” National World War II Museum, November 19, 2021.

Washburn, S. O. (1944) Letter to Mr. F. K. Fujita at Minidoka regarding his blocked bank account, March 24, 1944. Collection of Densho, Fujita Family Collection.

Young, Peter T. (2022) “Honolulu Sugar Company.” Images of Old Hawai'i, August 30, 2022.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime Economy

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime EconomyThe US economy grew during the war, and pop culture boomed. But it wasn't a "glittering consumer's paradise" for everyone.

-

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food Items

The Home Front During World War IIRationing of Non-Food ItemsRationed items included tires, cars, bicycles, gasoline, home heating fuels, shoes, stoves, footwear, and typewriters.

-

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan Orosa

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan OrosaMaria is best known as the inventor of banana ketchup. Her impact on Philippine life and her heroism on the home front is much greater.

Tags

- philippines

- filipino

- hawaii

- guam

- fdr

- world war ii

- world war ii home front

- japanese occupation

- currency

- coins

- economic history

- developing the american economy

- shaping the political landscape

- indigenous history

- national register of historic paces

- wwii

- wwii home front

- california

- san francisco

- oahu

- pearl harbor

- japan

- tule lake

- japanese american history

- asian american and pacific islander history

- illinois

- prisoner of war camp

- pennsylvania

- philadelphia

- denver

- colorado

- district of columbia

- italy

- germany

- african american history

- art history