Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

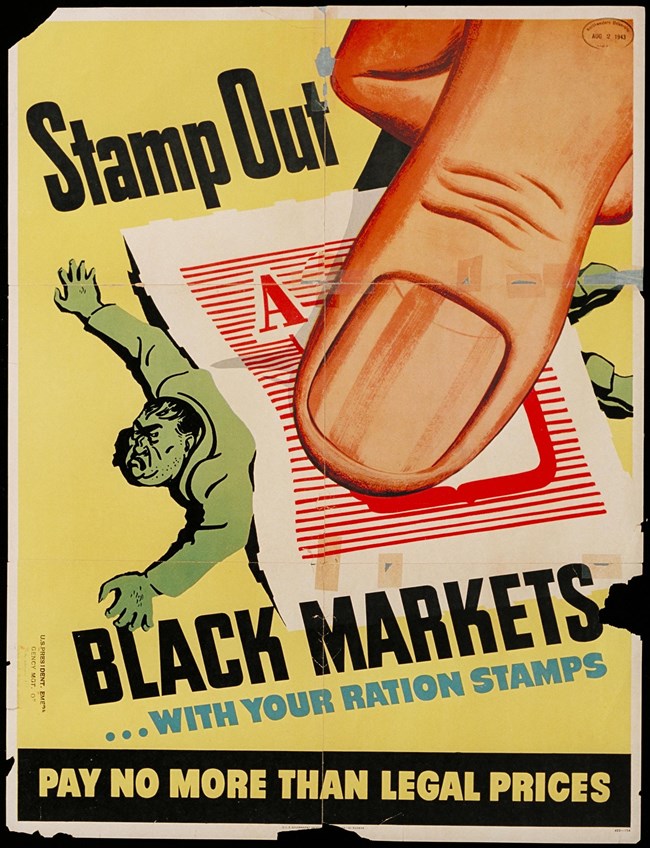

Collection of Northwestern University Libraries. ark:/81985/n2qn61c8x

Introduction

Rationing was the process by which the government limited access to items and materials needed for the war effort during World War II. It also helped to control inflation. Items rationed included meat, shoes, metals (including cans), tires, gasoline, and heating fuel. Regardless of rationing and other limits on available goods during the war, some people figured out how to profit and get what they wanted.

The “black market” describes trade in goods and services illicitly, or outside of legal systems (i.e. “I bought this steak on the black market”). It can also describe those goods and services (i.e. “This is a black market steak”). The term first appeared in the 1930s and gained traction with World War II rationing.[1] Despite general public support for the war effort, many did not like the inconvenience of doing without.[2]

Black market trade during World War II included steel, tires, coffee, sugar, gasoline, butter, potatoes, processed foods, and meat. The press regularly identified meat as the largest problem. The Office of Price Administration (OPA) estimated that as much as 17% of the nation’s meat trade was via the black market.[3] The press called it “meatlegging,” conjuring Prohibition-era bootlegging in illicit alcohol.[4]

Black markets also made up significant portions of the trade in other rationed goods. For example, approximately 5% of gasoline (2,500,000 gallons per day) was traded through forged and stolen coupons alone.[5]

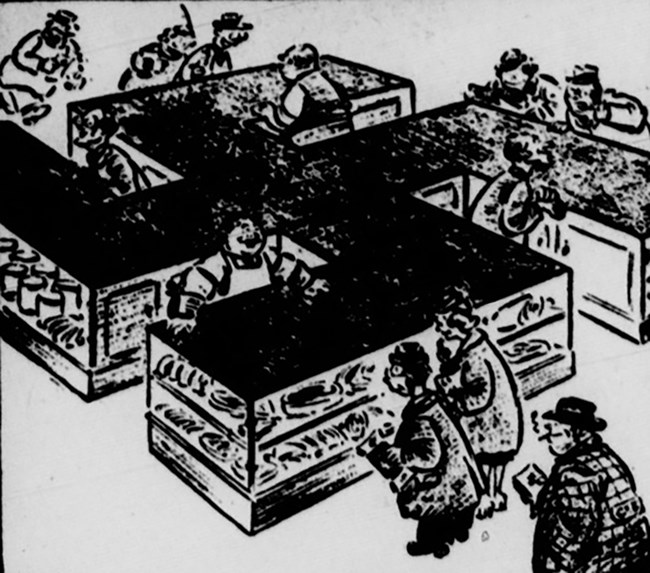

Daily Monitor Leader 1943 March 11, p. 7 (Chronicling America, Library of Congress).

Working Around the System

Illicit trade did not just happen at the grocery counter. Unscrupulous producers, suppliers, and consumers at all levels took part. Some were interested in lining their pockets; others didn’t see the problem if they bought on the black market “just this once.” Others were furious when they found out that Axis prisoners of war in the US were being fed rationed foods. Despite the fact that by international law, POWs had to be fed the same as the military of the country holding them, some felt no need to ration if it meant feeding the enemy.[6]

On the wholesale side, unscrupulous sellers took money above ceiling prices for their products. This was done by asking for more money outright; by accepting “gifts” after selling at ceiling prices or taking bribes. In Cleveland, a meat packer was offered a cash "bonus" of $75,000 (almost $1.3 million in 2023 dollars) if he would sell at ceiling prices.[7]

Meatleggers found another way around government controls by diverting livestock to black market slaughterhouses. One news story describes at least 800 head of cattle diverted from a single market on a single day.[8]

Not only were cattle diverted from regulated markets, but the makeshift slaughterhouses were not inspected for cleanliness or other food safety regulations. Nor were there systems to ensure that the livestock themselves were healthy and suitable for market. Epidemics of food poisoning and deaths were linked to black market beef.[9]

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/2017851792).

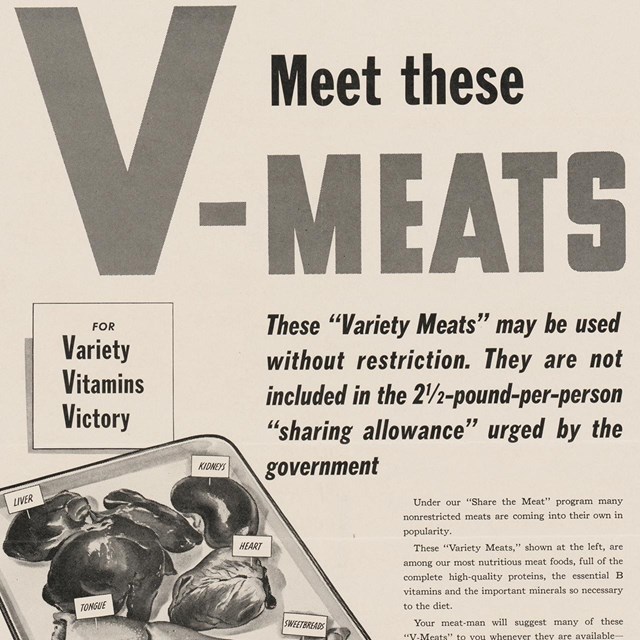

On the retail side, buyers and sellers found several ways to work around the ration limits. At the meat counter, sellers would include cuts that were not under price control (like livers, hearts, and brains) in with price-controlled meat. They would then sell it at ceiling prices (without the knowledge of the buyer).

Sellers would also charge for more weight than was being sold, or cut the number of needed ration points without lowering prices.[10] Buyers wrote checks for the legal price and handed over the difference in cash, or sweet talked their way out of using ration coupons. It was not uncommon for buyers to "buy" lower-quality cuts of meat and take home better cuts for dinner.[11]

There were also illicit markets for ration coupons themselves. Legitimate coupons and counterfeits were bought, sold, and traded against the law. Agents arrested one man in Detroit for selling 400 gasoline ration coupons for $57.50 (just over $985 in 2023). Over half of the coupons were counterfeit.[12]

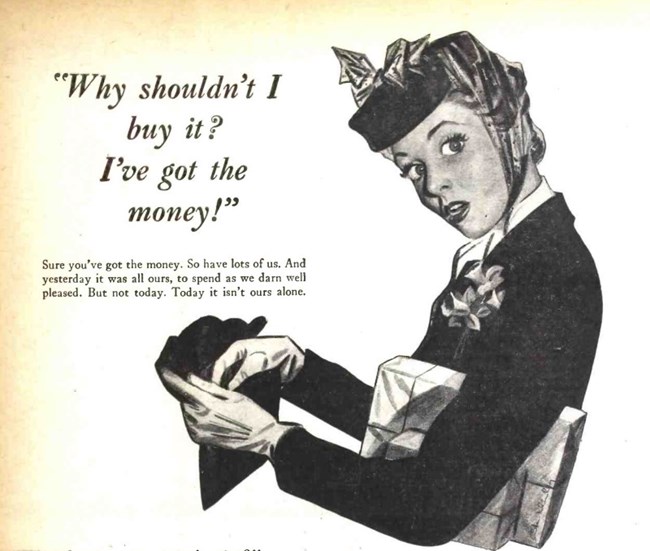

War Advertising Council, Radio Craft (magazine) March 1944, p. 357.

To counteract illicit trade in coupons, the OPA instructed sellers not to accept unendorsed or loose stamps. They were supposed to tear the stamps out of the ration books themselves.[13] Many looked the other way when consumers claimed their loose stamps had “fallen out” of their ration books – and surely some of them had! The ration books were made of cheap paper, and often fell apart.

There were several ration book forgery rings across the country, including ones run by organized crime. And there were targeted thefts of coupons from local ration boards, despite keeping them under lock and key. Thefts of restricted goods, including by siphoning gasoline, were not uncommon.[14] To curb the black markets, the government used several approaches.

Combating the Black Market

The biggest challenge to combating the black market was that many Americans were making lots of money working in war industries. These people had extra cash to spend to get what they wanted. A lot of what they wanted were things in short supply. And people were willing to pay more and more for them, driving inflation up for everyone.[15] The government spent a lot of resources trying to put a stop to the black market, from propaganda to enforcement and pulling cash out of the economy.

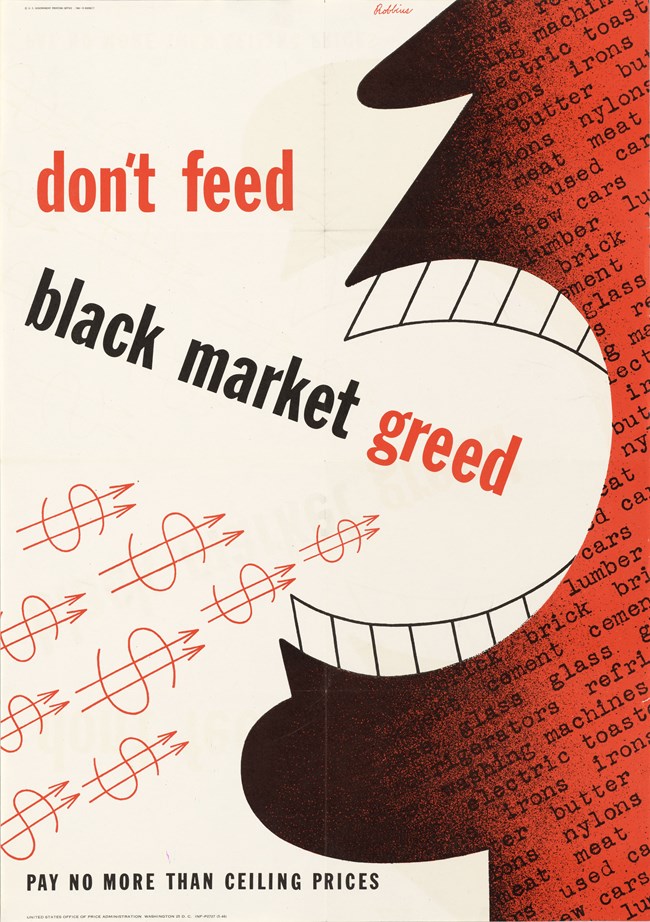

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 514140).

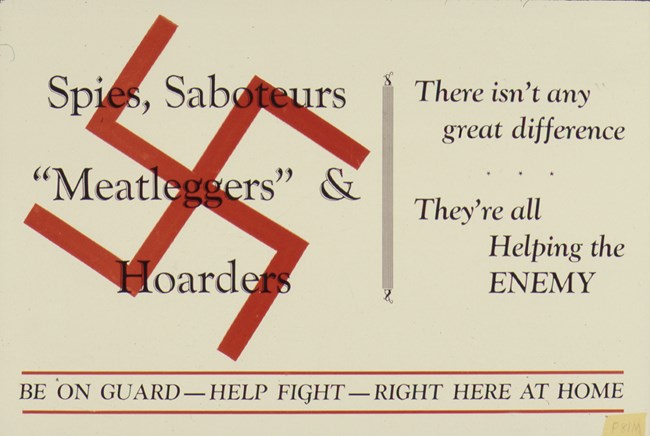

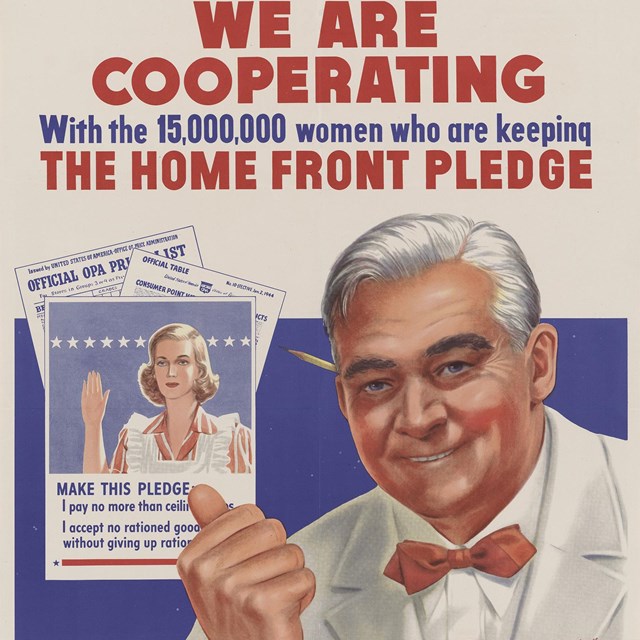

War-era posters put out by the government appealed to peoples’ better angels (“Don’t Feed Black Market Greed” - at left), their pride (“Sucker! If You Pay Over Ceiling Prices”), and their patriotism (“Spies, Saboteurs, “Meatleggers” & Hoarders: There isn’t any great difference. They’re all helping the enemy” - below).

Advertisements in women’s magazines and newspaper articles further discouraged people from participating.[16] One article written by the OPA argued that black markets helped the enemy, asserting that those who took part were guilty of “nothing short of treason.”[17]

The OPA led enforcement against the black market, often with the help of local, state, and other federal authorities. Consumers and other members of the public were encouraged to report violations, and people were hired to confirm the authenticity of coupons.[18]

There were definitely challenges. In New York, the state was unable to prosecute meat dealers who were taking bribes because no one would testify against them.[19] And there were just not that many OPA investigators – fewer than 3,000 were responsible for the whole country. They focused mainly on large-scale violations, not the “shabby little under-the-counter deals between butchers and their regular customers.”[20]

Despite the challenges, the OPA charged one in fifteen businesses with breaking the rationing and price laws during the war. These had penalties of up to a year in prison and a $5,000 fine.[21] The front page of the Washington, DC Evening Star for March 9, 1943 carried the article, “Black Market Meat Dealers Get Jail Terms.” Imposing jail terms of 6 months each and a total of $27,500 (about $480,000 in 2023) in fines on seven meat wholesalers, the judge said: “Black market operations must cease. The public will know from these sentences that unpatriotic profiteering at the expense of the war effort will not be tolerated.”[22] Other examples of punishment include: a man in California arrested for stealing 7 pairs of shoes sentenced to 6 months in jail or a $500 fine (about $8,500 in 2023); and a group of 10 people charged with counts up to grand larceny for stealing and selling black market tires.[23]

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 535194).

The government also used the economy to try to limit the effects of the black markets. Although organized crime got most of the press, much of the problem, according to officials, was economic. “Extra money in people’s pockets during the wartime is dangerous money,” wrote Maxwell Stewart in 1944. Also in 1944, a newspaper ad from Mrs. Smith’s Pie Company screams, “Joe’s Got a Fistful of Dangerous Dollars.”[24] Because only those with extra money could afford black market goods (and to otherwise curb inflation), the government sold war bonds and raised taxes predominantly to pull cash out of circulation. Raising money to fund the war was not the primary reason. [25]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Harper 2023.

[2] Gronek n.d.

[3] Thrasher 1943.

[4] Stewart 1944: 114; Roanoke Rapids Herald 1943; Thrasher 1943.

[5] Gronek n.d.; Midland Journal 1944.

[6] Youmans 1955: 106.

[7] LaGuardia 1944: 118; Thrasher 1943.

[8] Thrasher 1943.

[9] Evening Star 1943a.

[10] LaGuardia 1944: 119; United States Office of War Information 1943.

[11] Gronek n.d.; LaGuardia 1944: 119-120.

[12] Detroit Sunday Times 1944.

[13] For example, see Imperial Valley Press 1944.

[14] Dishman 2011; Gronek n.d.; Sundin 2022; United States Office of War Information 1945.

[15] Stewart 1944: 115-116.

[16] Detroit Sunday Times 1944; Hayes 2000: 4; Skyland Post 1944; Thrasher 1943.

[17] Roanoke Rapids Herald 1943.

[18] Dishman 2011.

[19] LaGuardia 1944: 118.

[20] Gronek n.d.; Stewart 1944: 114.

[21] Gronek n.d.

[22] Evening Star 1943b.

[23] Evening Star 1945; Sundin 2023.

[24] Stewart 1944; Morning Call 1944

[25] Harvey 1944: 110; Stewart 1944: 116.

Detroit Sunday Times (1944) “Grand Jury Probe Sought To Kill Gas Black Market.” Detroit Sunday Times, March 19, 1944, p. 3. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

Dishman, Katie (2011) “NARA Coast to Coast: The Coupon Craze of the 1940s.” NARAtions, December 19, 2011.

Evening Star (1945) “10 Men Arraigned on Charge of Selling Black Market Tires.” Evening Star (Washington, DC) April 26, 1945, p. B-1. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

--- (1943a) “Black Market Blamed for Chicago Epidemic: Contaminated Meat Held One Cause of Illness.” Evening Star (Washington, DC) February 26, 1943, p. B-13. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

--- (1943b) “Black Market Meat Dealers Get Jail Terms.” Evening Star (Washington, DC) March 9, 1943, p. 1. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

Gronek, Lauren (n.d.) “Black Markets During World War II.” In Michael Morrone et al. Perspectives on Black Markets V.2, chapter 4. Indiana University.

Harper, Douglas (2023) “Black Market.” Online Etymology Dictionary.

Harvey, Ray F. (1944) “Inflation and Nutrition.” In New York State Legislative Committee on Nutrition (ed.) Food – in War and in Peace. New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Nutrition, Albany, pp. 107-113.

Hayes, Joanne L. (2000) Grandma’s Wartime Kitchen: World War II and The Way We Cooked. St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Imperial Valley Press (1944) “OPA Aids Discuss Gasoline Dearth.” Imperial Valley Press (El Centro, CA) January 12, 1944, p. 1. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

LaGuardia, Fiorello H. (1944) “Some of Father Knickerbocker’s Food Problems.” In New York State Legislative Committee on Nutrition (ed.) Food – in War and in Peace. New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Nutrition, Albany, pp. 117-123.

Midland Journal (1944) “Campaign Against Black Market in Gasoline.” Midland Journal (Rising Sun, MD) September 1, 1944, p. 5.

Morning Call (1944) “Joe’s Got a Fistful of Dangerous Dollars” (advertisement). Morning Call (Allentown, PA), 1944. Collection of the John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History, Duke University Libraries.

Roanoke Rapids Herald (1943) “OPA Appeal is Made to Public to Stamp Out ‘Black Markets.’” Roanoke Rapids Herald (Roanoke Rapids, NC), March 11, 1943, p. A-6. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

Skyland Post (1944) “Black Market Patrons.” Skyland Post (West Jefferson, NC) January 13, 1944, p. 4. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

Stewart, Maxwell (1944) “Anatomy of the Black Market.” In New York State Legislative Committee on Nutrition (ed.) Food – in War and in Peace. New York State Joint Legislative Committee on Nutrition, Albany, pp. 114-116.

Sundin, Sarah (2023) “Make It Do: Shoe Rationing in World War II.” Today in World War II History, February 6, 2023.

--- (2022) “Make It Do: Gasoline Rationing in World War II.” Today in World War II History, July 22, 2022.

Thrasher, James (1943) “Black Markets Supply 17 Per Cent of Nation’s Meat: ‘Meatlegging’ Thrives on Greed, First Article in Series Reveals.” Daily Monitor Leader (Mount Clemens, MI), March 11, 1943, p. 7. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

United States Office of War Information (1945) “Town and Farm in Wartime.” Mississippi Enterprise (Jackson, MS) February 24, 1945, p. 2. Chronicling America, Library of Congress.

--- (1943) “If the ration points are cut, so must the prices be. Slashed points without slashed prices are one of the surest clues to black market meats.” Photo by Ann Rosener, United States Office of War Information. Collection of the Library of Congress.

Youmans, John B. (1955) “Nutrition.” In Preventive Medicine in World War II, Volume 3: Personal Health Measures and Immunization, ed. Ebbe C. Hoff, pp. 85-158. Office of the Surgeon General, Department of the Army, Washington, DC.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front During World War IIRestrictions and Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIRestrictions and RationingWartime shortages meant people had to do without or make due. Nylons, canned dog food, and sugar were some of the goods in short supply.

-

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime Economy

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime EconomyThe US economy grew during the war, and pop culture boomed. But it wasn't a "glittering consumer's paradise" for everyone.

-

The Home Front During World War IIMeat Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIMeat RationingMeat was on the ration list from March 1943 through November 1945, spurring Meatless Tuesdays, a thriving black market, and new recipes.