Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

The American Home Front Before World War II: The Greater United States

Collection of the Library of Congress (http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.rbc/General.13000).

The Guano Islands

In the early 1800s, farmers around the world were looking for ways to improve agricultural production. They were particularly interested in quick and economical ways to replenish soil quality. One method was to use guano – bird droppings – found in tropical areas where birds congregated. [2] By the 1840s, a very lucrative international guano trade had been established. High demand and limited supply drove prices up. The result was that individuals, companies, and nations scoured the globe for sources. [3]In 1856, the United States government passed the Guano Islands Act. It allowed Americans to claim territory with guano deposits on behalf of the US government. Almost 100 islands were claimed, and several were still part of the Greater United States when World War II broke out. [4] In the Pacific, these included Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, and Midway Atoll. After conflict with Britain about claims of Canton Island, the two countries agreed to a “condominium agreement” where the island was shared.[5] All of these islands and atolls remained uninhabited until the early 1900s. By 1903, the Commercial Pacific Company had built a telegraph station on Midway Atoll. With an average of 24 staff plus the Superintendent’s family, it was a key piece of the communications network connecting San Francisco to Manila in the Philippines via Hawai’i, Midway, and Guam. On July 4, 1903 the first round-the-world cable message traveled through the Midway cable offices, circumnavigating the globe in under 10 minutes. The cable station on Midway Atoll included imported soil and trees, the cable office, and living quarters for the operators who lived and worked there.[6]

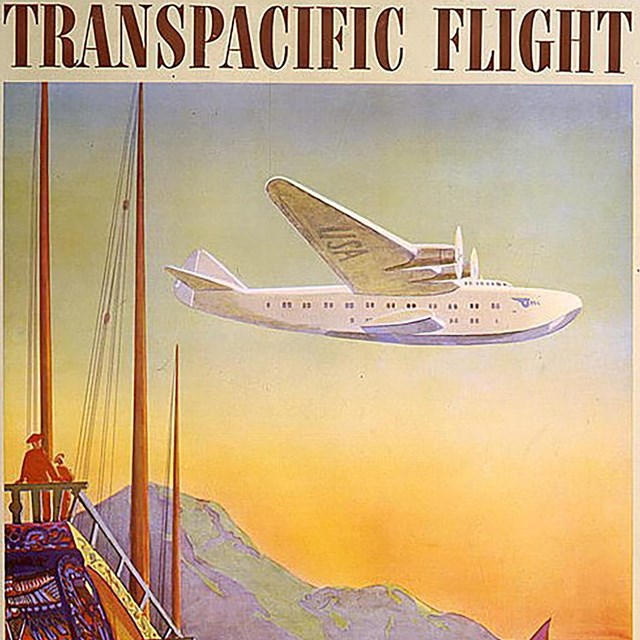

Baker Island, Howland Island, and Jarvis Island were populated in the 1930s as part of the American Equatorial Islands Colonization Project with three to four residents each. As part of the same project, seven Americans settled on Canton Island.[7] Dozens of Pan American Airways staff also lived on Midway and Canton beginning in the 1930s as the airline built bases to support trans-pacific air flights.

Collection of the Digital Archives of Hawai’i (PP-45-7-001).

Territory of Alaska

In 1867, United States purchased Alaska from Russia for $7.2 million (roughly $149 million in 2023). This put Alaska Native and other residents under American control. Alaska became an official territory of the US in 1912, and a state in 1959. In 1940, just over 72,500 people lived in Alaska.[8]Territory of Hawai’i

The Kingdom of Hawai’i was overthrown in 1893 by foreign landholders supported by the US Marines. They removed Queen Liliuokalani from power and imprisoned her in her palace. Against the wishes of many Native Hawaiians, Hawai’i became a territory of the United States in August, 1898. In 1940, just over 423,300 people lived in Hawai’i.[9]

Wikimedia.

Guam, The Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Wake Island

At the end of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the United States took control of several former Spanish colonies. These included the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. In 1899, the United States annexed Wake Island as a possible refueling and communications station between its new Pacific territories (Hawai’i, the Philippines, and Guam). In 1940, approximately 22,300 people lived on Guam; just over 16 million in the Philippines; and just under 1.9 million people lived in Puerto Rico. Dozens of Pan American Airways staff also lived on Wake Island beginning in the 1930s as the airline built bases to support trans-pacific air flights. [10]American Samoa

Samoa was an independent country when it became a center for trade and refueling in the Pacific in the 1850s. In the 1800s, Samoans disagreed about which family should rule. This conflict erupted in civil war in the 1880s and 1890s, and the US, Britain, and Germany took sides according to their own interests. They sent warships and troops, escalating the conflict. In December of 1899, these foreign powers signed an agreement that ended the war and divided Samoa. The eastern islands became part of the United States (American Samoa); the western islands went to Germany (now the independent nation of Samoa). In 1940, approximately 12,900 people lived on American Samoa.[11]

Collection of the Estate of Franklin D. Roosevelt, National Archives and Records Administration (MO 1953.424).

Panama Canal Zone

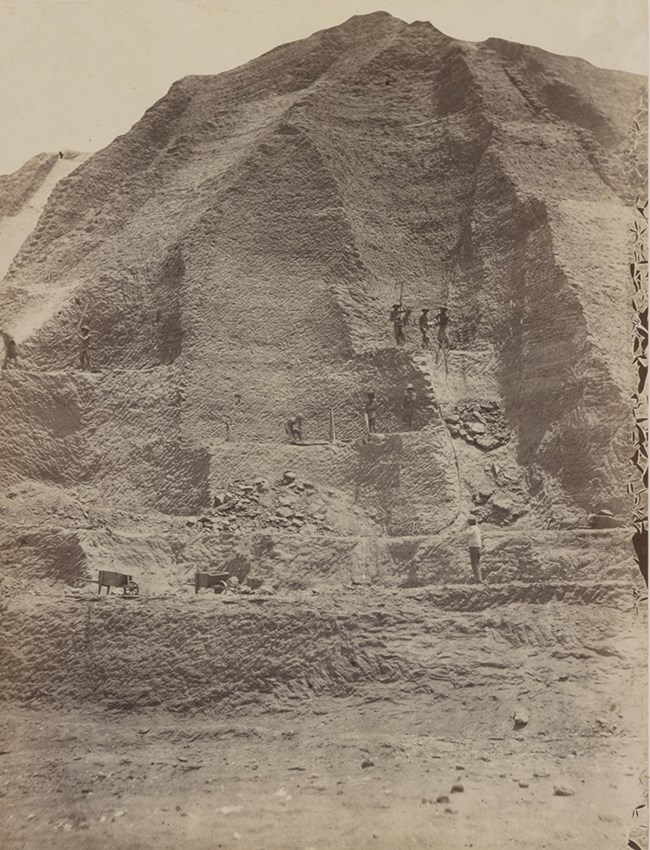

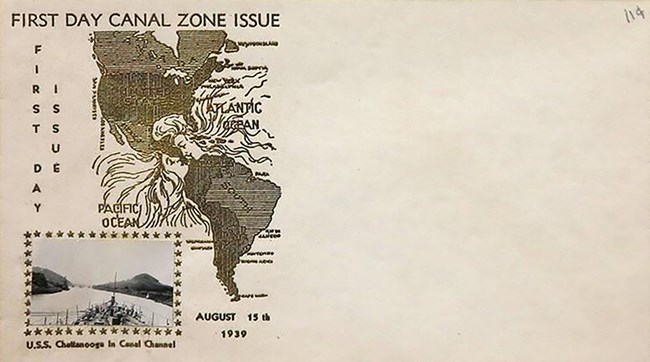

Before the Panama Canal was built, ships moving between the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans had to navigate the dangerous currents at the southern tip of South America. Among the countries looking to build a canal was the United States. When Panama became independent from Colombia (with the help of the United States), the new government gave the US the go-ahead to build the canal. In exchange for a one-time $10 million payment (approximately $343 million in 2023) and annual leasing fees from the Americans, the US received control of the canal and 5 miles on either side. This area was known as the Panama Canal Zone. Construction of the canal began in 1904 and in August 1914, the canal opened to commercial traffic. The population of the Panama Canal Zone in 1940 was just over 51,800. [12]U.S. Virgin Islands

When World War I began, the American government was worried that enemies would use the Dutch West Indies to launch attacks against Puerto Rico and the Panama Canal Zone. So, the United States approached Denmark about acquiring the islands (this had been an on-again/off-again conversation since the 1860s).[13] In 1917, just days before the US entered World War I, it took possession of the US Virgin Islands for a payment of $25 million (about $596 million in 2023). In 1940, there were just under 25,000 people living in the US Virgin Islands.[14]This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] Cushman 2013: 24-27; Roberts and Barrett 1984; Schmidt 1973: 124-125.

[3] Cushman 2013: 17; Wines 1985: 54-70; see also Skaggs 1994.

[4] As of 2022, all of these claims have been withdrawn, with the exception of: Baker Island, Howland Island, Jarvis Island, Johnston Atoll, Kingman Reef, Midway Atoll, Navassa Island, Bajo Nuevo Bank, Serranilla Bank, and Swains Island.

[5] Midway Atoll is made up of Sand, Easter, and Spit Islands. Baker, Howland, and Jarvis Islands are single islands. Canton Island was named after a whaling ship out of New Bedford, Massachusetts (Pan Am Historical Foundation n.d.a, n.d.b.).

[6] Burns 2016; Lyons 2005: 41-42; San Francisco Chronicle 1903. In 1922, the Commercial Pacific Cable Company compound (known by 1939 as “Cable City”) included the cable office, plus an additional four two-story buildings with 20 rooms each, used as living quarters for the Superintendent and family, staff sleeping quarters, a kitchen-dining-recreation building (including an icemaker that could make 300 pounds of ice each day and a large freezer), and living quarters for the Chinese servants. Basements of the buildings were used for storage, laundry, machine shop and other utilities. There was also about an acre of kitchen garden, created using imported soil. In 1923, there were also a wooden bungalow, 12 outhouses, barns, and sheds. A 1938 report describes livestock at Midway including 2 cows, a bull, 10 pigs, 50 turkeys, and 250 chickens. The resupply ship arrived every three months, weather permitting (Burns 2016).

The first message through Midway was from President Theodore Roosevelt in Oyster Bay, New York to Governor Taft in Manila, The Philippines. It was sent on July 4, 1903 and read: “To Governor Taft, Manila. I open the American Pacific cable with greetings to you and the people of the Philippines.” Taft replied, “To the President: The Filipino people and the Americans resident in these islands are glad to present their respectful greetings and congratulations to the President of the United States conveyed over the cable with which American enterprise has girdled the Pacific, thereby rendering much easier and more frequent communication between the two countries. It will certainly lead to closer union and a better mutual understanding of each other’s aims and sympathies, and to their common interests in the prosperity of the Philippines and the education and development of the Filipinos. It is not inappropriate to incorporate in this, the first message across the Pacific from the Philippines to America, the earnest plea for the reduction of the tariff on Filipino products in accordance with the broad and liberal spirit which the American people desire to manifest toward the Philippines, and of which you have been an earnest exponent” (San Francisco Chronicle 1903; see also Gill 2022).

[7] See Kamehameha School Archives (n.d.) and University of Hawai’i at Mānoa (n.d.).

[8] United States Department of Commerce 19421: 1191. Alaska includes the chain of Aleutian Islands that extend west, separating the Pacific Ocean from the Bering Sea. Most of the 14 large and 55 smaller islands are part of Alaska; the part of the chain furthest west belongs to Russia.

[9] United States Department of Commerce 19421: 1209. Hawai’i is made up of 137 islands. The seven that are inhabited are Ni’ihau, Kaua’i, O’ahu, Moloka’i, Lāna’i, Maui, and Hawai’I (often called the Big Island to prevent confusion between the island and the state).

[10] United States Department of Commerce 1941: 2, 1942: 1205, 1221. Guam is the southernmost island in the group of islands known as the Mariana Archipelago. For details on Guam’s pre-World War II history, see Viernes (2008). Spain sold the rest of the islands as the Northern Mariana Islands to Germany at the end of the Spanish-American War (Central Intelligence Agency 2023a, 2023c, 2023e; Lyons 2005; National World War II Museum n.d.). The indigenous people of Guam are the Chamorro (also spelled CHamoru); the Taino are indigenous to Puerto Rico and other areas of the Caribbean; the Philippines is home to several indigenous groups (Minority Rights Group International n.d.). The Philippines is made up of over 7,600 islands, the largest of which are Luzon, Mindanao, Sumar, Negros, and Palawan. Only about 2,000 of the islands are inhabited. The territory of Puerto Rico includes over 140 islands, islets, atolls, and keys. The islands of Puerto Rico, Culebra, and Vieques are inhabited; a handful of others have private residences, government research stations, and hotels on them. Wake Island is actually an atoll made up of Wake Islet, Wilkes Islet, and Peale Islet. Guam is a single island.

[11] United States Department of Commerce 1942: 1201. Britain gave up their interests in the Samoan Islands in exchange for other territories in the Pacific and West Africa. American Samoa is made up of five main islands (Tutuila, Aunu’u, Ofu, Olosega, and Ta’ū) and two atolls (Swains Atoll and Rose Atoll). All but Rose Atoll are inhabited. The Samoans are the indigenous people of American Samoa (Central Intelligence Agency 2023d). In negotiating the Tripartite Convention, the US Department of State wrote to Germany: “The President…fully shares in the desire expressed by the prince chancellor to bring the blessings of peace and order to the remote and feeble community of semi-civilized people inhabiting the islands of Samoa, and … clearly recognizes the duty of the powerful nations of Christendom to deal with these people in a spirit of magnanimity and benevolence” (United States Department of State 1889). This idea that non-Western societies were semi-civilized and feeble, needing the protection and guidance of Western civilizations was a common one, and had been used to justify colonial expansion for centuries. See also Masterman (1934) and Kennedy (1974).

[12] Canal de Panamá 2023a, 2023b; Central Intelligence Agency 2023b; United States Department of Commerce 1942: 1217.

[13] Danish National Archives 2017; Hoover 1926: 503.

[14] Rogers 1917: 736; United States Department of Commerce 1942: 1235. The US Virgin Islands include the three main islands of Saint Croix, Saint Thomas, and Saint John as well as about 50 other minor islands and cays. The indigenous people of the US Virgin Islands are the Taino.

Canal de Panamá (2023a) “American Canal Construction.” Canal de Panamá.

--- (2023b) “End of the Construction.” Canal de Panamá.

Central Intelligence Agency (2023a) “Guam.” The World Factbook, January 11, 2023.

--- (2023b) “Panama.” The World Factbook, February 6, 2023.

--- (2023c) “Puerto Rico.” The World Factbook, February 6, 2023.

--- (2023d) “Samoa.” The World Factbook, February 3, 2023

--- (2023e) “Wake Island.” The World Factbook, January 10, 2023.

Cushman, Gregory T. (2013) Guano and the Opening of the Pacific World: A Global Ecological History. Cambridge University Press, New York.

Danish National Archives (2017) “The Danish West-Indies.” Danish National Archives (Rigsarkivet).

Gill, Kathy E. (2022) “The First Round-the-World Telegram Foreshadowed a Shift in Global News.” WiredPen, July 4, 2022.

Hoover, Donald D. (1926) “The Virgin Islands Under American Rule.” Foreign Affairs 4(3): 503-506.

Kamehameha Schools Archives (n.d.) “Hui Panalā‘au, Real Life Kamehameha Schools Survivors.” Kamehameha Schools Archives.

Kennedy, Paul M. (1974) The Samoan Tangle: A Study in Anglo-German-American Relations, 1878-1900. University of Queensland Press, Australia.

Lyons, Jeffrey K. (2005) “The Pacific Cable, Hawai’i, and Global Communication.” The Hawaiian Journal of History 39: 35-52.

Masterman, Sylvia (1934) The Origins of International Rivalry in Samoa: 1845-1884. George Allen and Unwin, London.

Minority Rights Group International (n.d.) “Philippines: Indigenous Peoples.” World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples.

National World War II Museum (n.d.) “Battle of Bataan.” National World War II Museum.

Pan Am Historical Foundation (n.d. a) “A New Route to Auckland.” Pan Am Historical Foundation.

--- (n.d. b) “Canton Island: Pan Am’s Critical Stop-Over in the Pacific.” Pan Am Historical Foundation.

Roberts, Daniel G. and David Barrett (1984) “Nightsoil Disposal Practices of the 19th Century and the Origin of Artifacts in Plowzone Proveniences.” Historical Archaeology 18(1): 108-115.

Rogers, Lindsay (1917) “News and Notes: Government of the Virgin Islands.” American Political Science Review 11(4): 736-737.

San Francisco Chronicle (1903) “Dispatch Circles Globe in Less Than Ten Minutes.” San Francisco Chronicle, July 5, 1903, p. 17.

Schmidt, Hubert G. (1973) Agriculture in New Jersey: A Three-Hundred-Year History. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Skaggs, Jimmy M. (1994) The Great Guano Rush: Entrepreneurs and American Overseas Expansion. St. Martin’s Griffin, New York.

United States Department of Commerce (1941) Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1940. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

---- (1942) Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940 : Population : Volume 1 : Number of Inhabitants. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

United States Department of State (1889) “Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, Transmitted to Congress, with the Annual Message of the President, December 3, 1889: Mr. Blaine to Messrs. Kasson, Phelps, and Bates.” Office of the Historian,

University of Hawai’i at Mānoa (n.d.) “Hui Panalāʻau: Hawaiian Colonists in the Pacific, 1935-1942.” Scholar Space: Center for Oral History.

Viernes, James Perez (2008) “Fanhasso I Taotao Sumay: Displacement, Dispossession, and Survival in Guam.” Master’s thesis, Pacific Island Studies, University of Hawai’i.

Wines, Richard A. (1985) Fertilizer in America: From Waste Recycling to Resource Exploitation. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front Before World War IIWWI, Great Depression, and the New Deal

The Home Front Before World War IIWWI, Great Depression, and the New DealCircumstances leading up and during World War I, the Great Depression and the New Deal all shaped the US World War II home front.

-

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPlan for the Worst, Hope for the Best

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPlan for the Worst, Hope for the BestAmericans knew of the growing conflict during the 1930s. While trying to stay out of it, the government was also quietly preparing for war.

-

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPan American Airways on the Home Front

Home Front Buildup to World War IIPan American Airways on the Home FrontPan American pioneered the transpacific air route, extending the American home front westward across the Pacific.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- home front

- homefront

- world war ii home front

- military history

- agricultural history

- spanish-american war

- world war i

- geography

- us in the world community

- international relations

- history of technology

- history of communications

- transportation history

- alaska

- american samoa

- philippines

- guam

- hawaii

- native hawaiian

- indigenous history

- baker island

- california

- san francisco

- howland island

- jarvis island

- midway atoll

- wake island

- puerto rico

- us virgin islands

- panama canal zone

- germany

- denmark

- united kingdom of great britain and northern ireland

- pacific islander history

- samoan

- taino

- chamorro

- alaska natives