Last updated: February 22, 2024

Article

The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II: The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

Buffalo Courier Express (Buffalo, New York) September 2, 1939, p. 1.

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 513808).

For years, FDR had quietly been preparing for the possibility of America’s involvement in the conflict. Publicly, he maintained neutrality. In his Fireside Chat on September 3, 1939 he told Americans: “Let no man or woman thoughtlessly or falsely talk of America sending its armies to European fields… This nation will remain a neutral nation.”[1] As the war in Europe intensified, Congress allowed trade with belligerent nations – but only if they paid cash and transported their own goods. This “cash-and-carry” policy was designed to keep Americans out of the conflict.[2] With a market opening for buyers, American factories increased their production. Unemployment continued to fall, and inflation became a concern.[3]

When German forces captured France in June of 1940, Britain appeared on the brink of falling. This would have left little (if any) opposition to the spread of fascism around the world.[4] Winston Churchill took to the radio to appeal to the public for American intervention, while also working government to government with FDR and Congress.[5] In 1940, Roosevelt won his third term. During the election, he walked the fine line of both campaigning to keep the US out of the war while also affirming the need for America to protect itself. The public, uneasy at the global situation, increasingly supported a military draft.[6]

Photo by the War Department (VIRIN: 430407-O-ZZ999-001).

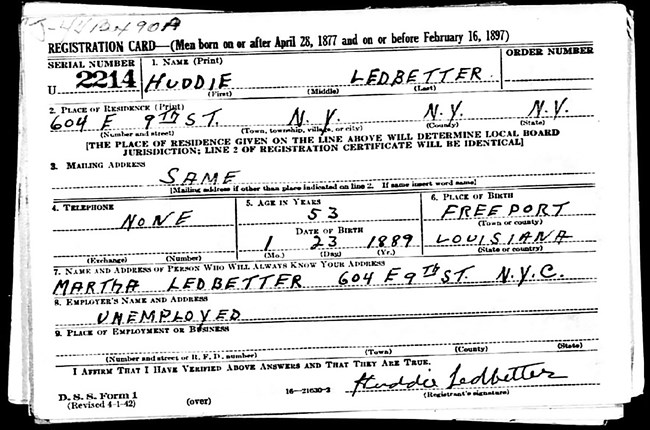

The Selective Training and Service Act of 1940

In September, 1940 the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 became law -- the first peacetime draft in American history. It required all men who had turned 21 but who were not yet 36 years old to register. Before the draft, the Army and the Navy had a combined force of about 265,000.[7] Within a month, more than 16 million men were on the rolls and almost a million were drafted into service. Draftees were selected by lottery. The first lottery took place on October 29, 1940. In DC, papers with numbers 1 to 7,836 printed on them were loaded into small capsules. These were put into a large glass bowl (which had also been used in the World War I draft) for selection. Officials stirred the capsules using a wooden spoon carved from a piece of Independence Hall. A blindfolded Secretary of War Henry Stimson reached into the bowl and selected a capsule. President Roosevelt read out the number, 158, and cross the country, in thousands of local draft districts, men assigned that number had to report for service. [8]Provisions in the Act spelled out who could serve. Draftees were required to serve at least one year, plus up to 10 years in the reserves. And though there was not supposed to any racial discrimination, the military remained segregated. White men who met the criteria were drafted immediately. Especially early on, draft boards sent most Black men home. Those who were drafted were assigned to a very few segregated units. [9] Any man not meeting the medical requirements were classified as 4-F (unfit for service) and sent home. This included many suffering from malnourishment. Men with dependents (wives and children) were exempt from service. This led to a spike in marriages. Also able to defer were those working in essential industries and farming, and those attending college. Many of these criteria changed over the course of the war as the military needed more and more service members. [10]

Screen capture from Universal Newsreel, Volume 12, Release 924, October 30, 1940. MCA/Universal Pictures Collection, National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 234272595).

Unemployment fell as men went into military training and into increasing numbers of jobs. But despite the law, the draft, and the clearly intensifying conflicts, there was resistance and confusion. Those drafted were not really sure what their role was in a technically neutral US. Manufacturers were making good profits from consumers as the Great Depression was ending, and they were reluctant to lose that profit by converting to military production.[13] In the factories, unions were working to organize labor and pushing for more benefits – emboldened by the increased demands for workers. In the months before the US entered World War II, more than 2.3 million unionized American workers walked out in over 4,200 strike actions. This was the highest level of strike actions in United States history.[14]

Collection of the National Postal Museum (2002.2035.586).

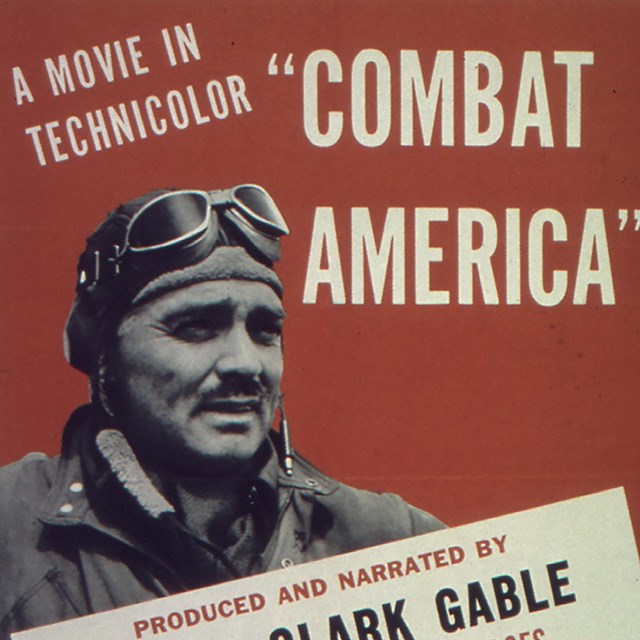

The Arsenal of Democracy

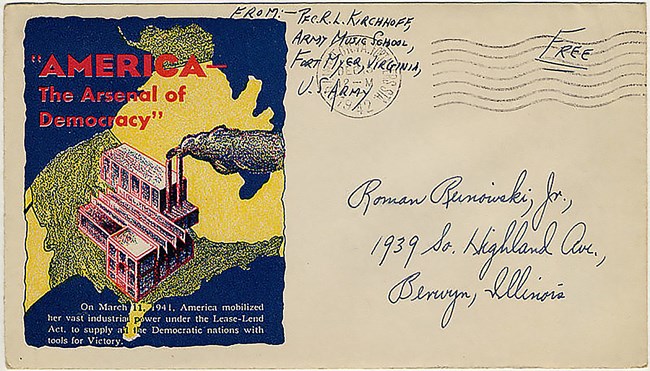

Tensions in the Pacific continued to escalate as FDR limited trade with Japan. And in Europe, the war was going poorly for the British.[15] The Blitz had begun and London was under German bombardment day and night. Reporter Edward Murrow was there, reporting for CBS radio. American citizens listened intently as one of their own reported on the devastation against the backdrop of anti-aircraft shots and enemy planes and bombs.[16]The President again took to the airwaves at the end of 1940. He talked about enemy spies at work in the United States; warned against profiteering; and accused those wanting to stay out of the war of helping the enemy. Continuing to insist that Americans would not send troops to Europe or Asia, FDR conceded that peace with the Axis was impossible. To keep America out of the war, America needed to support Britain and their allies. America had to become the “great arsenal of democracy.”[17]

Just over a week later, FDR stood in front of Congress and outlined the “four essential human freedoms” that the US was helping to defend. These were freedom of speech, freedom to worship in one’s own way, freedom from want, and freedom from fear.[18] After months of negotiations, Congress passed the Lend-Lease Act in March of 1941. It permitted the US to gift, lend, or lease military supplies to any nation “vital to the defense of the United States.” Because they were not being sold, the cash- portion of the cash-and-carry limitations of the Neutrality Acts did not apply.[19] With the stroke of a pen, the federal government became the customer for military goods – to the tune of $7 billion for the first orders. They also appropriated $13.7 billion for the military (more than six times the $2.2 billion spent on defense the year before.) Unemployment fell below 10% for the first time since before the Great Depression, and servicemen were called up and sent to training camps by the hundreds of thousands.[20]

Collection of the New-York Historical Society Museum & Library (2002.1.4595)

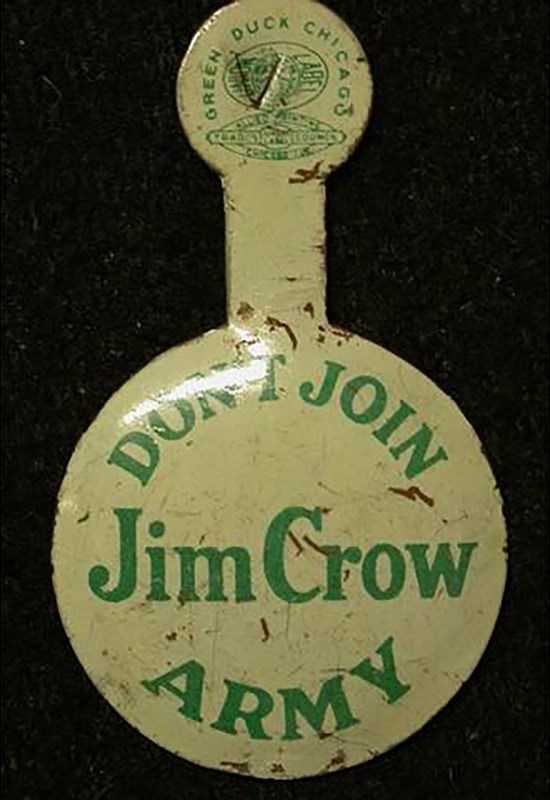

Despite the law, however, Black men and women still encountered discrimination, including being assigned the dirtiest and most dangerous jobs. The irony of working and fighting for democracy overseas while living in a country that treated them as second class citizens was not lost on African Americans. Some, remembering the lack of respect they received after World War I, advocated staying out of the military. One collar clip that was circulating read, “Don’t Join Jim Crow Army.” There was also a nation-wide “Double V” (Double Victory) campaign inspired by a letter published in the Pittsburgh Courier. It called for Victory Abroad for democracy, and Victory at Home referring to a defeat of racism in the US.[22]

On July 26, 1941, in part to keep Japan from attacking Russia (a British ally), FDR froze all Japanese assets in the US. This effectively cut Japan off from American oil.[23] Although Japan and the US had been going back and forth for years about trade, this was a provocation too far for the Japanese. Diplomacy failed, and on December 7, 1941 Japanese forces attacked.

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] United States Department of State n.d..

[3] Fletcher 2022; Roosevelt 1940b.

[4] National World War II Museum n.d.c.

[5] Churchill 1940.

[6] National World War II Museum n.d.c.

[7] Evans 2006; Kennedy 1999: 459; National World War II Museum n.d.c; Roosevelt 1940b; US Congress 1940.

[8] Kennedy 1999: 459, 495; National World War II Museum n.d.c; United States Congress 1940; Zebrowski 2007.

[9] Kennedy 1999: 459, 495; National World War II Museum n.d.c; United States Congress 1940; Zebrowski 2007.

[10] United States Congress 1940; Zebrowski 2007. In practice, only those ages 18 to 44 were called up to serve.

[11] Martin 2020; United States Congress 1940; Wagner 2022. Patapsco Camp in Elkridge, Maryland was the first work site established in the Civilian Public Service program. Some members of the Civilian Public Service program worked in mental institutions. What they saw there horrified them. They reported and photographed conditions in the institutions. An article, “Bedlam 1946,” appeared in Life magazine in May of 1946, shocking the country (Maisel 1946). You can also read an inmate’s story of confinement as a conscientious objector held at the Federal Correctional Institution in Danbury, Connecticut in Schoenfeld 1950.

[12] Ohly 1999; United States Congress 1940.

[13] Graff 2022; Kennedy 1999: 309, 477, 495.

[14] Southern Labor Archives 2019.

[15] Kennedy 1999: 505-507.

[16] Brady 2014; Edwards 2004. You can hear a clip of Edward R. Murrow’s September 22, 1940 live broadcast from a London rooftop during an air raid as part of Musser 2007. Several of Murrow’s wartime recordings are available on A Reporter Remembers – Vol. 1: The War Years via the Internet Archive.

[17] National World War II Museum n.d.a; Roosevelt 1940a.

[18] Roosevelt 1941.

[19] United States Congress 1941. Recipients were still required to “carry” their own purchases for a few more months. In October 1941, Congress lifted the bans on arming merchant vessels and from those ships entering belligerent ports or combat zones (United States Department of State n.d.).

[20] Kennedy 1999: 469, 476.

[21] Young 2019: 47. Randolph later pressured President Truman to desegregate the military (done by Executive Order 9981 in 1948). Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King, Jr. organized the1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom – a direct descendant of the civil rights work undertaken in World War II.

[22] National World War II Museum n.d.b; Nielsen 2020; Pleasant 2020. Even the Germans saw the hypocrisy – and used it to try to convince African American soldiers to switch sides.

[23] Kennedy 1999: 510.

Churchill, Winston (1940) “We Shall Fight on the Beaches [June 4, 1940].” 1940: The Finest Hour, International Churchill Society.

Edwards, Bob (2004) “Edward R. Murrow Broadcast from London (September 21, 1940). Added to the National Registry: 2004.” National Recording Preservation Board, Library of Congress.

Evans, Harold (2006) “Foreword.” In Alistair Cooke, The American Home Front, 1941-1942. Grove Press, New York City.

Fletcher, Alden A. (2022). “Roosevelt’s “Limited” National Emergency: Crisis Powers in the Emergency Proclamation and Economic Studies of 1939.” Journal of National Security Law & Policy 12(2): 379-415.

Graff, Cory (2022) “Making Automobiles Last During World War II.” National World War II Museum, January 6, 2022.

Kennedy, David M. (1999) Freedom From Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945. Oxford University Press, New York.

Maisel, Albert Q. (1946) “Bedlam 1946: Most U.S. Mental Hospitals are a Shame and a Disgrace.” Life, May 6, 1946, p. 102-118.

Martin, Kali (2020) “Alternative Service: Conscientious Objectors and Civilian Public Service in World War II.” National World War II Museum, October 16, 2020.

National World War II Museum (n.d.a) “Becoming the Arsenal of Democracy.” National World War II Museum.

--- (n.d.b) “Double V Victory.” National World War II Museum.

--- (n.d.c) “Research Starters: The Draft and World War II.” National World War II Museum.

Nielsen, Euella A. (2020) “The Double V Campaign (1942-1945).” BlackPast, July 1, 2020.

Ohly, John H. (1999) Industrialists in Olive Drab: The Emergency Operation of Private Industries During World War II. Center of Military History, Washington, DC.

Pleasant, Keri (2020) “Honoring Black History World War II Service to the Nation.” U.S. Army, February 27, 2020.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (1941) “President Roosevelt’s Annual Message (Four Freedoms) to Congress (1941)” [January 6, 1941]. Milestone Documents, National Archives and Records Administration.

--- (1940a) “On National Security. December 29, 1940.” The American Presidency Project.

--- (1940b) “On National Defense. May 26, 1940.” The American Presidency Project.

--- (1939) “On the European War. September 3, 1939.” The American Presidency Project.

Schoenfeld, Howard (1950) “The Danbury Story.” In Prison Etiquette: The Convict’s Compendium of Useful Information” by The Inmates, p. 12-27. Collection of Western Connecticut State University Archives, Rare Books.

Southern Labor Archives (2019) “Southern Labor Archives: Work n’ Progress – Lessons and Stories: Part IV: Labor, the Depression, the New Deal, and WWII.” Southern Labor Archives, Georgia State University Library, May 20, 2019.

United States Congress (1940) “Public Law 76-783. An Act to Provide for the Common Defense by Increasing the Personnel of the Armed Forces of the United States and Providing for its Training.” United States Congress, September 16, 1940.

--- (1941) “Public Law 77-11. An Act Further to Promote the Defense of the United States, and for Other Purposes.” United States Congress, March 11, 1941.

United States Department of State (n.d.) “The Neutrality Acts, 1930s.” Milestones in the History of U.S. Foreign Relations, Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State.

United States Office of Facts and Figures (1942) “Report to the Nation: The American Preparation for War.” United States Office of Facts and Figures, January 1942.

Wagner, Ella (2022) “Patapsco Camp (WWII Civilian Public Service Site).” National Park Service, July 15, 2022.

Young, Curtis (2019) “A. Philip Randolph.” In Kinshasha Holman Conwill (ed.), We Return Fighting: World War I and the Shaping of Modern Black Identity, pp. 44-47. Smithsonian Books, Washington, D.C.

Zebrowski, Carl (2007) “Your Number’s Up!” America in WWII, December 2007.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

-

The Home Front Before World War IIWWI, Great Depression, and the New Deal

The Home Front Before World War IIWWI, Great Depression, and the New DealCircumstances leading up and during World War I, the Great Depression and the New Deal all shaped the US World War II home front.

-

The Home Front During World War IIIncarceration and Martial Law

The Home Front During World War IIIncarceration and Martial LawThe US government incarcerated many Americans and others in camps and prisons across the country. Martial law was declared in Hawaii.

-

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime Economy

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime EconomyThe US economy grew during the war, and pop culture boomed. But it wasn't a "glittering consumer's paradise" for everyone.