Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

Collection of the Library of Congress (HABS DC, WASH, 220—21).

Like many American industries, the Servel Company in Evansville, Indiana (an American World War II Heritage City) switched from manufacturing civilian goods to full-scale wartime production. And like other companies, they worked to stay top of the mind of consumers so that people wouldn’t forget them, and would buy their products after the war.

The Servel Company was founded in 1923 as the National Electric Products Company. They became Servel Manufacturing in 1925. The name comes from combining the first letters from the words in its slogan, “Serving Electric.” They made the cabinets for gas-powered refrigerators. The refrigeration machinery was made in Newburgh, New York.[1]

Before the invention of mechanical refrigeration, there were several ways to keep perishables fresh. One was to use large blocks of ice (this is why we sometimes call refrigerators ice boxes). In the early 1800s, ice harvesting became a commercial business.

Ice was cut from freshwater lakes and ponds and stored in huge warehouses. It was then shipped all over the world, as well as sold locally.[2] Households would have blocks of ice weighing up to 100 pounds each delivered by the local iceman. These would be placed in a compartment in an insulated icebox; the food would go into a separate section.[3]

Collection of the Evansville Museum of Arts, History & Science, Gift of Charles Daum (1993.032.0002).

The first system for mechanical refrigeration was patented in 1834 in Massachusetts. Improvements were made throughout the 1800s, and commercial refrigeration was widespread as the 1900s began. It wasn’t until the late 1910s that the first (very expensive) electric refrigerators were marketed for use in peoples’ homes.[4] They cost between $500 and $1,000 at the time (approximately $7,500 to $15,000 in 2023 dollars).

In the late 1920s, fridges became increasingly common in private homes as more and more people lived in urban areas where food was trucked in and had to be kept fresh. The Electric Home and Farm Authority, one of the New Deal programs of the Great Depression, provided low-cost financing to Americans for the purchase of electric appliances like refrigerators, putting them in reach of more consumers.[5]

Before the war, Servel was best known for their refrigerators. By 1941, they had made and sold over 2 million of them. On April 30, 1942 the last civilian products at Servel rolled off the lines. As at other manufacturers, all production capacity was slated for military use.[6] What each factory made was considered secret, to prevent enemy sabotage.

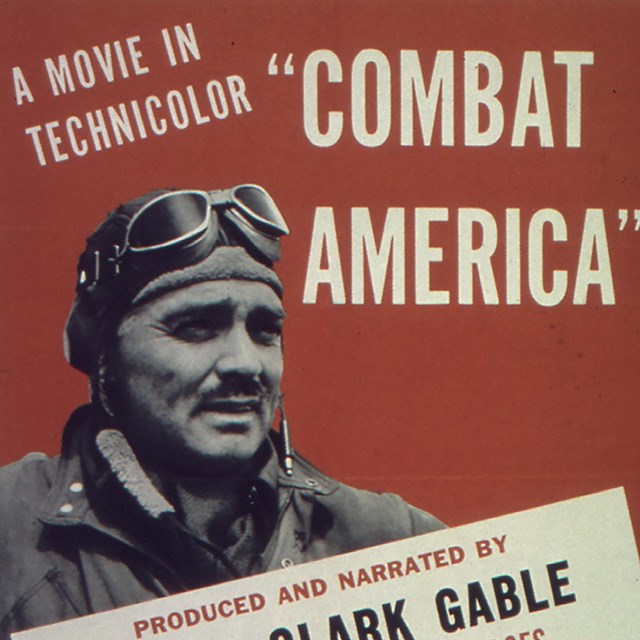

But after the war, an Evansville Courier article shared Servel’s wartime production: “field kitchen fire units, … P-47 Thunderbolt wings (over 6,000 pairs), 37mm and 40mm cartridge cases, breach cases, anti-tank mines, land mines, gasoline heaters, lanterns, cylinder heads and other parts for aircraft engines.”[7] Also during the war, Servel published the “Vita-Min-Go” game to help families eat to the Basic 7 nutritional guidelines.[8]

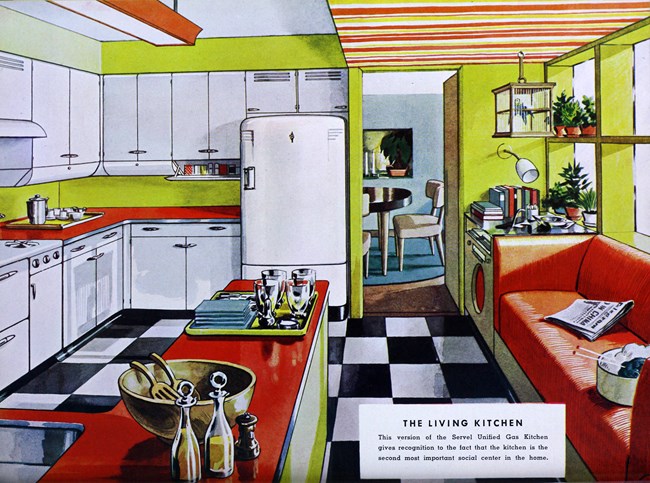

After the war, Servel returned to making consumer goods, including household and commercial refrigerators, gas water heaters, and air conditioning unit.[9] Employing as many as 7,000 workers, Servel made their gas-powered refrigerators until 1957, when they went out of business. Consumers were no longer interested in gas appliances, and were embracing all-electric kitchens. Whirlpool bought the Servel factory in 1958 as part of its expansion. The company closed its Evansville plant in June 2010, moving refrigerator production to Mexico.[10]

Collection of the Evansville Vanderburgh Public Library, Central Library Indiana Collection (621.57 SERVE).

Even though they hadn’t been manufactured in over 40 years, enough Servel refrigerators remained in use that in 1998 they were recalled by the government. Fridges that had not been properly maintained risked releasing carbon monoxide into people’s homes, causing sickness and death. In 2022, a fire destroyed part of what was left of the old Servel factory complex.[11]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

[1] Good 2020.

[2] Grahn 2015; McCabe 1994: 44; Whittemore 1994: 32.

[3] Grahn 2015; McCabe 1994: 44.

[4] Grahn 2015; McCabe 1994: 44; Whirlpool 2023.

[5] Grahn 2015; Thompson 2021. Another New Deal program supporting increased consumer use of refrigerators was the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). They brought electricity to rural areas – home to about half of America’s population at the time. While urban Americans had access to electric service for many years, power companies were uninterested in running power lines into rural areas because they were not profitable. When the REA was founded, 90% of rural homes had no electric power. By 1940, that number had dropped to 40% (Shipley 2020).

[6] Servel, Inc. 1942b.

[7] Coker 2012.

[8] Servel, Inc. 1942a.

[9] Good 2020.

[10] Davis 2010; Lonnberg 2022.

[11] Lonnberg 2022; United States Consumer Product Safety Commission 1998.

[12] The Woodrow Wilson House at 2340 S Street NW, Washington, DC was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966. It was designated a National Historic Landmark on July 19, 1964. It has been documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Coker, David (2012) “Servel Has a Long Proud History in Evansville.” Courier & Press, August 11, 2012.

Davis, Rich (2010) “The Last Refrigerator from Evansville.” Indiana Economic Digest, April 11, 2010.

Good, Stephen (2020) “Servel, Inc. Papers, 1937-1955” (finding aid). William Henry Smith Memorial Library, Indiana Historical Society, September 2020.

Grahn, Emma (2025) “Keeping Your [Food] Cool: From Ice Harvesting to Electric Refrigeration.” O Say Can You See? Stories from the Museum, National Museum of American History, April 29, 2015.

Lonnberg, Thomas R. (2022) “The Hercules and Servel Legacy.” Evansville Museum.

McCabe, C. (1994) “On Ice.” Early American Life 25(6): 40-44.

Servel, Inc. (1942a) “Vita-Min-Go” (game). Life on the Home Front Web Exhibit (Oregon State Archives), “Food is a Weapon: Nutrition Programs Fight for Victory.” Oregon State Archives, Defense Council Records, Box 30, Folder 14.

--- (1942b) “Wartime Message” (advertisement). Life Magazine, March 23, 1942, pp. 103.

Shipley, Jonathan (2020) “A Light Went On: New Deal Rural Electrification Act.” The Living New Deal, December 5, 2020.

Thompson, Lisa (2021) “Electric Home and Farm Authority (1934).” The Living New Deal, September 7, 2021.

United States Consumer Product Safety Commission (1998) “CSPC Warns That Old Servel Gas Refrigerators Still In Use Can Be Deadly.” United States Consumer Product Safety Commission, July 22, 1998.

Whirlpool (2023) “The History of the Refrigerator: Ancient Origins to Today.” Whirlpool.

Whittemore, E.C. (1994) “19th Century Ice Harvesting.” Antiques Magazine 29(7): 32-34.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

The Home Front After World War IIThe End of the War and Its Legacies

The Home Front After World War IIThe End of the War and Its LegaciesThe war did not end all at once. Its legacies continue shaping life in the US and around the world, even today.

-

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime Economy

The Home Front During World War IIThe Wartime EconomyThe US economy grew during the war, and pop culture boomed. But it wasn't a "glittering consumer's paradise" for everyone.

-

The Home Front During World War IIMaterial Drives

The Home Front During World War IIMaterial DrivesCelebrities including Mickey Mouse and Bing Crosby urged Americans to “Salvage for Victory” and “Get In The Scrap.”

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- wwii home front

- wwii homefront

- history of science

- history of food

- foodways

- government history

- military history

- great depression

- new deal

- indiana

- awwiihc

- american world war ii heritage city program

- business history

- industrial history

- national register of historic places

- national historic district

- habs

- historic american buildings survey

- evansville

- massachusetts

- international relations

- washington d.c.

- washington dc

- president wilson

- woodrow wilson

- developing the american economy

- technology

- science and technology