Last updated: June 12, 2024

Article

Preserving WWII Internment History in Texas

This is a transcript of a presentation at the Preserving U.S. Military Heritage: World War II to the Cold War, June 4-6, 2019, held in Fredericksburg, TX. Watch a non-audio described version of the presentation on YouTube.

Preserving Second World War Internment History: A Texas Perspective

Presenter: Dr. Lila Rakoczy

Abstract

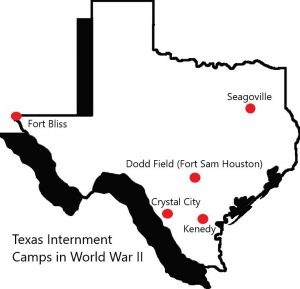

One of the more forgotten aspects of Second World War history is the internment of foreign nationals and American citizens within the Lone Star State. These internment camps were located in five places: Crystal City, Seagoville, Kenedy, Dodd Field, and Fort Bliss. Through four Japanese American Confinement Sites Program (JACS) grants between 2009 and 2015 the Texas Historical Commission (THC) has worked to preserve the history of all five internment camps. These projects include oral history interviews, onsite interpretation, new printed brochures, dedicated webpages, archaeological and condition surveys, and a National Register of Historic Places nomination. Over the last several years THC has built on this foundation by forging partnerships with St. Mary’s University, survivors of internment and their families, and the Briscoe Center for American History to ensure that private documents are collected, digitized, and disseminated to the wider public. These different approaches have helped preserve the history of sites threatened by structural loss, new uses, and restricted or limited access.

Presentation

Dr. Lila Rakoczy: I’m a World War I and early modern siege warfare specialists, so I'd like to talk to you about World War II.

The internment of thousands of Japanese Americans is one of the most recognized aspects of the home front during World War II. In contrast, the role Texas played in World War II civilian internment is less widely known among the general public, even within the state. Internment arguably continues to be seen as something that happened elsewhere, in the abstract, or else on the West Coast and divorced from its Texas connections.

Equally problematic is the general lack of recognition of other aspects of the internment program, that ethnic Germans and Italians, foreign as well as American-born, were also impacted. That some were removed from Latin America and brought to the United States against their will, despite no evidence that they were a danger to American national security. And that some of these same individuals, including American citizens, were deported to Axis countries in exchange for Americans held in Germany, Italy, or Japan.

Over the last 20 years, commendable efforts have been made to combat this general lack of awareness. Texas-specific works, such as those produced by Robert Thonhoff and Jan Jarboe Russell, have both drawn much needed attention to two Texas sites. These have served as a good historical backdrop to some of the firsthand accounts produced by former Texas internees. In the last decade, these attempts to publicize the mass internment that took place here 75 years ago has only intensified.

Notably, the Texas State Historical Association added an entry on Texas World War II internment to its popular digital resource, the Handbook of Texas Online. And over the last couple of years, the subject has received increased scrutiny by Texas journalists, as well as serving as the focus of both a young adult novel and documentary short.

As the primary state agency tasked with historic preservation, the Texas Historical Commission, or THC for short, has played a unique role in helping to amplify this history. It has done this through a variety of its established government programs, but particularly through its Military Sites Program. This paper will summarize the key activities carried out by THC within the last 15 years, and the partnerships that formed in the process with former internees and their families, local communities, federal agencies, and other government entities at the state, county, and local level.

It will also highlight THC's three main objectives in all its internment-related projects to date: improving onsite and local interpretation, disseminating information to a wider audience, particularly through digital means, and preserving the current tangible and intangible heritage while carrying out new investigations. The achievements here are modest but ongoing, and I think reflect the realities often faced by historic preservationists when confronted with challenging sites. We do what we can, where we can, with what we have.

Kenedy and Crystal City, suffer from accessibility and engagement issues of a different type. Both are located in rural areas of South Texas. Kenedy has about 3,500, population of 3,500, Crystal City, about double that.

Both have suffered the loss of majority of their wartime structures. With these challenges in mind, THC staff gave serious thought to both the desirability and feasibility of what could be delivered to improve the preservation and interpretation of these five sites.

So I just want to share with you, before I get into the specifics, this is a list of what I'm calling the deliverables that THC produced during this period through four successive JACS grants. If any of you would like to add anything to this list, please come and talk to me. But I'd like to talk a little bit more about some of these in greater depth.

And the first of the three primary objectives that I mentioned earlier was onsite and local interpretation. And this fits into THC's model, which stresses heritage tourism and getting local partners engaged in the process.

So those of you who are familiar with Texas, and those of you who like to mock Texas for it, one of the things that we are known for is our State Historical Marker Program. In Texas, this commemoration goes back as far as the 1850s. In the decades that followed, various government representatives sporadically would continue to commemorate sites within Texas, often working in conjunction with groups such as the Daughters of the American Revolution to install granite monuments and plaques at sites deemed to be important to Texas history.

In 1962, this process was formalized by the creation of the current State of Texas Historical Marker Program, first administered by the Texas State Historical Survey Committee. To date, more than 16,000 of these iconic markers have been placed throughout the state's 254 counties, now under the authority of the Texas Historical Commission.

A major transformation came in 2006 when the THC initiated its Undertold Marker Program. The Undertold Marker Program prioritizes marginalized and underrepresented histories, and for the first time, allowed applications to originate outside of a county historical commission. So with the creation of the Undertold Markers, this allowed us to, within a period of a few years, establish markers at each of these sites. So THC has placed State Historical Markers at all five internment sites and in addition, Kenedy has the added distinction of having a designated Historic Texas Cemetery within its boundaries. And you should be able to see it on the far right. It's slightly different in look to the others.

So I'm going to talk a lot about Crystal City. Crystal City arguably has a disproportionate amount of deliverables associated with it for reasons that I'll talk about. But as you can see from this slide, this is an aerial representation, modern, and the red stars mark the locations where we placed historic panels, not our State Historical Markers, but interpretive panels. THC chose to build on the momentum of markers by obtaining a second JACS grant that provided additional interpretation to aid visitors in better understanding the site. This was considered especially necessary due to the sprawling size of the former camp, which was approximately 300 acres in size. It began much smaller, but over time the US government acquired more land.

It has also changed drastically since the 1940s, the near total loss of its original structures and also the addition of new buildings into the landscape. So for these panels, content was assembled by THC staff for a total of eight. They were thematic, and as you can see, we tried to place them throughout the camp at sites that would be particularly meaningful. So for example, the site of a former swimming pool, which I believe is there, it's there.

The intended audience for these panels was residents from the adjacent housing development, students from the school that occupies part of the former camp site, and also former internees and their families who periodically make return visits to the site. These thematic panels contain a variety of information pertaining to work and leisure time within the camp. For children, because this was a family internment camp, school and play time. Other darker aspects that were covered include the removal of people of Japanese and German descent from Latin America, and in some cases, the deportation of German and Italian descent individuals during the war in exchange for Americans held abroad. So these were some of the topics covered in the panels.

So we acknowledged... Oh, and here I've included all eight panels, so that you can get a sense of what the panels look like. These panels were dedicated in November of 2011. And you can see on the left, this is the day of the dedication. And some of the individuals that are gathered around it are actually former internees and their family members. So we were very fortunate that several of them were able to actually join us for the dedication.

We also continue... oh, it's just... oh, there it is. We're also very fortunate in that its proximity to the school means that schoolchildren continue to have access to this. And I took the picture on the right on the day of a much later dedication. And what was particularly gratifying is that the children ran straight over, started looking at the panels. And their teacher confirmed that they had actually been covering a World War II internment that very day. So he might've just been saying that for my benefit, but I choose to believe him.

We also recognize, however, that not all individuals would have the ability to go to the former camp site or traverse over all of the acreage, some of which is in private property or private hands. So we created five pop-up banner stands and donated them to Crystal City officials, and also the local school there, so that they could actually use them. And it was very important to us that, with them being pop-up banner stands, they're very portable. So they can used and reused at events. They can also be loaned to other organizations such as civic groups.

So one of our priorities was also to get this information to a wider audience outside of the local community. And one of the easiest ways to do that, I say easiest, it's not easy, is through digital content. One of our JACS grants actually paid for the creation of six new web pages for THC. So once the web pages were complete and went live, we actually went from having virtually little to no information about Texas internment on our website to having arguably one of the best sources, certainly for Texas public history websites at that time on the subject of Texas internment. So much so that if you continue to do Google searches on internment camps, Crystal City, Texas, we're routinely one of the top two or three hits that you will get.

We also created, with the JACS grant, two brochures, which, one of those I passed out to you today. It's a testimony to how, I hesitate to say popular, but we've actually run out of the Crystal City brochures. Inquiries regarding the Crystal City Family Internment Camp are fairly steady at certainly my program within Texas Historical Commission. So the Crystal City Site continues to be one of the sites that people are particularly engaged with.

We also run a mobile app tour. And this was already in existence at the time that we received our grant for digital content. In particular, we were creating the World War II on the Texas Homefront Texas Time Travel Tours. The Texas Time Travel Tours, if you're not familiar with them, they are place-based navigation. And they allow travelers to visit the sites grouped by select themes. So of course this theme was World War II, but we have other themes as well. One of our more recent ones is on World War I, but we also have African American heritage in Texas and various other topics. So I encourage you to check that out.

Most recently, in 2017, the Lone Star Chapter of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences recognized THC with a Lonestar Emmy Award for its World War I and World War II digital content. So we were very, very proud of that.

And finally, the third priority, recognizing that we had limited resources to achieve this, was what new information, beyond interpretation, could we perhaps generate for future generations? And one of the ways that we did that was quite ambitious. So one of our last two JACS-funded projects, we had been alerted to the existence of a mural at Seagoville Prison that was thought to have been painted by one or more Japanese American internees. It was located in one of the light wells. And it's very difficult to make out, but this is the light well looking down. So there's a mural here, and here, and here. And they are in very poor condition.

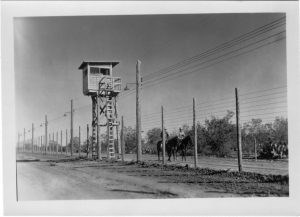

Our working hypothesis was that the pastoral mural scenes might have been created as a form of visual escape for internees wanting to take a break from their immediate landscape of guard towers and barbed wire. Past Matters was hired to provide a condition assessment and provide recommendations for potential future preservation efforts. In May of 2017, staff traveled to the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC in College Park. But unfortunately, we failed to turn up any smoking guns, so to speak, of the identity of the individual or group of individuals who might have painted the murals.

So due in part to security concerns, this is after all, a working prison, what we decided here is that we weren't going to be able to install permanent interpretation panels like we had at Crystal City. So again, we went for the pop-up banner stand route. And these are five that are being completed as we speak. And they will be handed over to Seagoville Public Library and the warden of the prison. And again, for use as they see fit.

And the second ambitious project that we set upon was a five-day archeological survey at Crystal City, which was carried out in April of 2013. Due to time and money constraints, the decision was made to focus on two areas with a high chance of yielding information. The former location of two bath houses near the camp pool, as well as the below-ground remains of the Japanese elementary school.

Once again, we were disappointed. No artifacts dating to the site's World War II period were found. However, the excavation did have an unexpected silver lining. The final report highlighted the potential survival of archeological features in other parts of the site as yet uninvestigated, which provided crucial in establishing a much desired designation for the site on the National Register of Historic Places. So we're hoping that a follow-up archeological investigation might take place at some point in the future.

And finally, one byproduct of our years of networking with former internees, their families and friends, and groups such as the German American Internee Coalition, was the incredible resource of having firsthand eye witnesses to internment. Consequently, between 2009 and 2011, 13 individuals agreed to donate an oral history interview to the THC. Five were civilians who had either lived in the shadow of the camp or worked inside one. The rest were former Texas internees of Japanese or German descent, all of whom were either American-born or brought to the United States from Latin America and held in Crystal City.

The original recordings are held by the Texas Historical Commission in Austin. But in December of last year, transcripts for most of these interviews were made available on our web pages. The interviews often reveal intimate, more reflective observations about internment. One common recollection, for instance, was of parents attempting to shield their children by making their immediate environment less dreary. Former internee Art Jacobs recalled his parents' efforts soon after their arrival.

"The first thing that my dad did, my mother went into our quarters. And they were tarpaper shacks, you know, roughly. They were tarpapered on the outside and there was no finishing on the inside. So my dad got some sort of wallboard. I don't know where he got it from. And then he painted the inside of our house. And he had all kinds of techniques that he used, rags to roll colors down, to make it look like what have you. So he made our quarters look like real quarters, you know what I'm saying? He spruced them right up."

Internees recalled the gardening efforts taking place in their midst, and of catching or being terrified of the snakes they sometimes stumbled upon. Due to the severe South Texas heat, the camp pool was another topic that came up frequently. A young Art Jacobs learned to dive in it. His fond memories were matched by fellow internee Moonyeen Thornton, who recalled pretending to be a mermaid in its waters.

Bessie Masuda's memories of the pool, however, were much darker. “The deep end was roped off, but if you went near it, it was very slimy. It sloped to a point where if you did go down, you would slip and go to the deep end. We were playing, and somehow this friend of mine, she decided, we didn't even know she was to go to the deep side. But I guess she wanted to know what it was like. And so she slipped, and started splashing around and yelling. I thought, 'Oh my God, she might be drowning.' I got all my friends, because there were, I don't know how many, maybe six, seven of us. We held hands, tried to reach out to her. But it wasn't easy, because we were slipping too. Finally, I just gave up. I said, 'No, no, no, pull me back.' I said to them, 'I can't reach her. By that time, someone had called for help. It was too late. The first time I've experienced something like that, you know. I had nightmares for the longest time. Today I don't like water."

Collectively, the 13 oral histories cover too many topics to adequately cover here. The anger and helplessness of an American teenager and his family, sent to a country that viewed them with suspicion. Multinational family rounded up in Costa Rica, sent to a remote place in Texas, and facing the possibility of being separated and deported to different nations. Children too young to understand what was happening, but impacted for years by the scars inflicted on their parents and older siblings.

So I'd like to leave on a higher note or a more positive note. As THC's association with Texas World War II internment history became solidified in the public consciousness, or at least in people's Google searches, a surprising development occurred. People assumed we were an archival repository and offered to donate internment-related artifacts, documents, photographs, and other items. True, as a state agency with certain regulatory and records retention responsibilities, we are a repository of sorts. But beyond our statutory duty to preserve and maintain the 22 State Historic Sites already in our care, we simply were not equipped to acquire and properly store, display, and otherwise make available to the public the various documents that were occasionally offered to us.

To address this problem, the Texas Historical Commission and Friends of the THC forged a partnership in 2018 with the Research and Collections Division of the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History in Austin. THC agreed to transition three internment-related collections into their permanent care: the Ben Sira Construction Company photographs, and you can see some images from that collection here; the Fossati Family Correspondence; and the James O'Rourke Crystal City Internment Camp papers.

So the collection that would come to be known as the Fossati Family Collection arrived on my desk in April of 2018. And you can see at the bottom there what it came in. It consisted of 12 handwritten and typed letters in three different languages, sent between various members of the Fossati family. Some interned in Crystal City, the rest back in California. The donor was unrelated to the Fossati family, but revealed an interesting backstory to how he acquired the letters. He described living next to "two elderly Italian sisters" in the 1980s. And when the last one died, their possessions were thrown into a nearby alley. He saw the unusual return address, Crystal City Internment Camp, and thought they looked "historical." So he saved them from the alley and stored them away, and 30 years later, they found their way to me.

My favorite of that collection is the patriarch of the family is complaining to his relatives in California about the location he's in being dry. And in this case, he means his inability to get access to wine. So I thought that was quite funny.

The final group of Crystal City-related documents that came into our temporary custody is truly special. It includes the official government, as well as personal post-war correspondence of the Camp Commander Joseph O'Rourke, as well as photographs of him and internees and others, and a copy of his personal diary. Of particular interest are the numerous letters to O'Rourke from internees during their internment, but even more intriguingly, for years afterwards. And so I've included a photograph of a visit that O'Rourke and his wife made to California at the request of a former interned family. And so by all accounts, he was considered to be a fair man given the circumstances that he was working in.

But those are in the process. All three of those collections are in the process of being digitized by the Briscoe Center. And I'm pleased to report that they will be made available to the wider public later this year.

So at that, I can take any questions.

Questions

Speaker 1: Well that was fascinating. I wondered if you have had contact with or made any connections between any of the POWs who are buried at Fort Bliss National Cemetery and Fort Sam National Cemetery.

Lila Rakoczy: I have not. If you have information to share, I would love to speak with you afterwards. Oh...

Speaker 1: I'm fishing.

Lila Rakoczy: Unfortunately... I will add to that that, sadly, the Fort Bliss and Dodd Field sites are grossly underrepresented in our catalog of information. And it's not for lack of interest on our part. A lot of it is just serendipitous. The contacts that you make have a particular connection to a site, and you have to follow that lead. And it just worked out that Crystal City kept coming up again and again. And so that was sort of what we did. But it's definitely something that I want to pursue, those two sites in particular.

Mary Striegel: Who else has a question?

Speaker 2: Since my facility in Arizona is only about 60 miles south of Poston, I've done a lot of research and done a presentation regarding Poston and the War Relocation Authority. Today, now this is the second time I'm seeing camps that apparently had nothing to do with the WRA. So I'm wondering under what authority and whose jurisdiction were these people being interned.

Lila Rakoczy: So it was the Department of Justice, administered through different federal agencies associated. It also changes over time a little bit, so it's a difficult question for me to answer. I can speak with you afterwards if you'd like.

Speaker 3: Since the internment camps are governed, or were set up by a law, a federal law, I think, I understand-

Lila Rakoczy: Yes, executive order.

Speaker 3: Does that provide somehow for ongoing maintenance funds? How do you go... You've done an amazing job in the immediate time. How do you go forward and maintain this level of commitment to interpreting the site?

Lila Rakoczy: We would like to continue to apply for funding from the Japanese American Confinement Sites Program. It's simply a matter of prioritizing which projects and deciding what we want to go forward on. But as long as that program continues to be funded, we're going to continue to put together projects and ask for funding.

Speaker Bio

A native of Huntsville, Texas, Lila Rakoczy has a B.A. in history from King’s College London and an MA and PhD in archaeology from the University of York. For six years, she worked in the heritage sector in Britain, engaging with the community and working with the public to identify, record, and understand the historical artifacts and buildings in their midst. More recently she spent three years as a Visiting Assistant Professor of History at Sam Houston State University. She currently heads the Military Sites and Oral History Program at the Texas Historical Commission.

Read other articles from this symposium, Preserving U.S. Military Heritage World War II to the Cold War, or learn more about the National Center for Preservation Technology and Training.