Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

The American Home Front During World War II: A Date That Will Live in Infamy

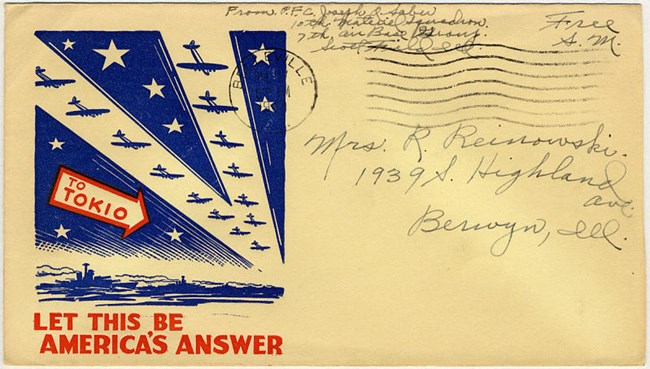

Collection of the National Postal Museum (2002.2035.234).

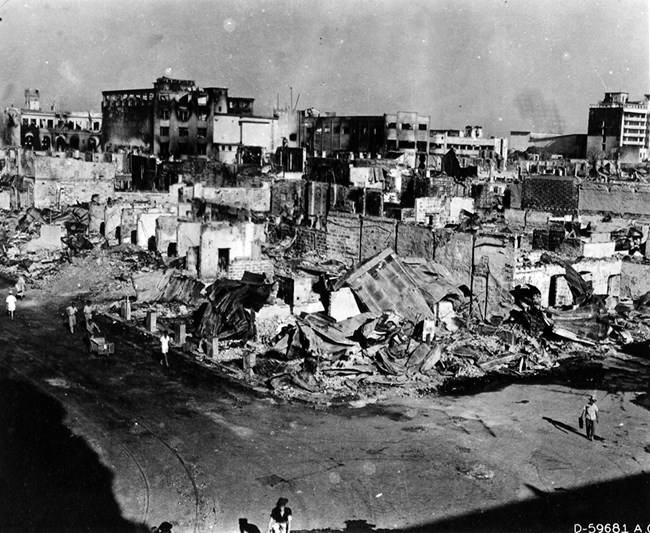

Repelled by American forces in many of these locations, Japan quickly took control of Guam, the Philippines, and Wake Island. Civilians on these islands suffered greatly under Japanese rule. They lost their homes and family members, and were subjected to forced marches and forced labor, internment and incarceration, starvation, injury, and execution. While the US eventually retook these pieces of the American home front, the damage done by both sides was often extreme.

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 204952271).

The next day, FDR called December 7, 1941 “a date that will live in infamy.” Referencing the Japanese attacks on Hawai’i, Guam, the Philippines, Wake Island, and Midway Atoll, he asked Congress to declare war on Japan. With only one vote against, Congress complied.[7] Allied with Japan, Germany and Italy declared war on the US, and America was fighting a world war on multiple fronts.

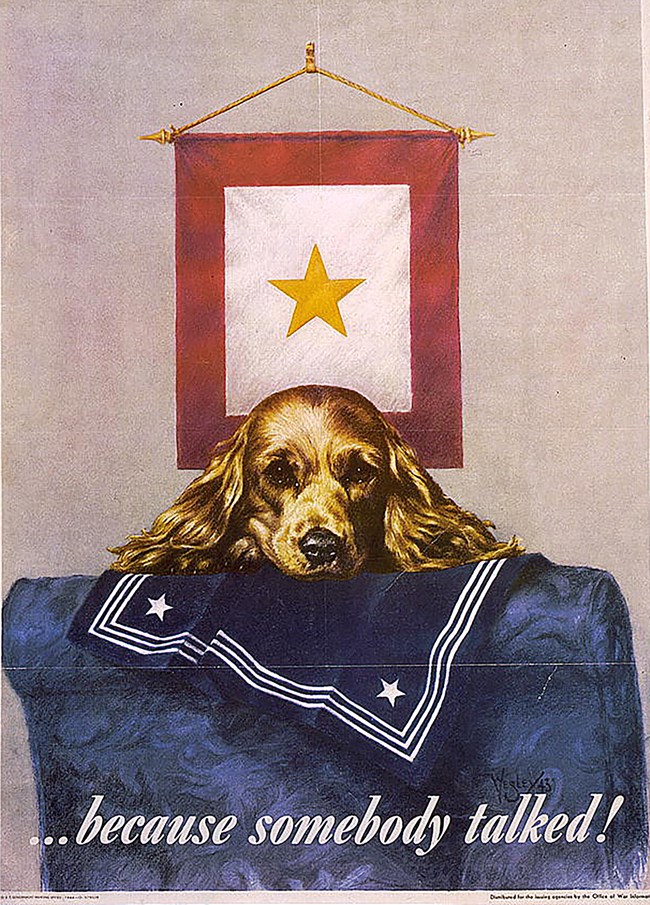

Collection of the Library of Congress (https://lccn.loc.gov/93511606).

A New Landscape

A lot changed after the US entered the war. Although the American people, industry, and the government had done a lot in the years before, there was still much to do. New factories were built and old ones expanded and retooled.[8] Millions of Americans moved into industrial areas for work creating localized housing shortages. Women and enemy prisoners of war filled jobs left vacant when service-age men went to war. The draft was expanded, requiring those between 18 and their 65th birthday to register, and fathers were no longer exempted.[9] African Americans began to be drafted in larger numbers than before. Between the draft and industrial expansion, unemployment dropped to 1.2% by 1944.[10]The war effort was everywhere. Products disappeared from the market. Areas around military training facilities and ports of embarkation were dense with uniforms. Radio shows, Hollywood films, and books for all ages had Patriotic themes. Everywhere you turned, posters, the government, and celebrities were reminding you to buy war bonds; to save your scrap; to plant victory gardens; to be cautious. Decals, pins, posters and jewelry appeared, all bearing the rallying cry: “Remember Pearl Harbor!” To provide military access to settlements in Alaska, the construction of the Alaska Highway was approved and begun early in 1942.[11]

The war also reached directly into American homes. Families hung blue and gold stars in windows. The government implemented rationing. Civilians collected and donated materials needed for the war effort and they planted victory gardens, preserving the produce. Some Americans sought out illicit markets for rationed products. Many found themselves in very different working and living conditions than they were used to. Some found themselves interned and incarcerated. Others found themselves living under military rule. And some found themselves, their homes, and businesses under attack.[12]

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] McDonough 1991; Patel 2017. At 7:50am Oahu time (12:50pm Eastern time), the Japanese signaled for a general attack on Pearl Harbor; the attack ended at 10am (3pm Eastern time) when American forces turned the second wave of Japanese attackers back to their carriers.

[3] History Matters n.d.; McDonough 1991. You can hear the broadcast at the History Matters website. In Manitowoc, Wisconsin (an American World War II Heritage City), the local radio station stayed open 24 hours a day so residents could come in and get the latest news from the teletype.

[4] Smith 2014.

[5] Brechin 2014; Roosevelt, Eleanor 1941 Pearl Harbor.

[6] Bailey and Farber 1993: 819; McDonough 1991; Scheiber and Scheiber 2020, 2016.

[7] Roosevelt 1941 date of infamy. Pacifist Jeanette Rankin was the sole dissenting vote.

[8] Tassava 2008.

[9] United States Congress 1940 selective.

[10] Tassava 2008.

[11] Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities n.d.; Jacobs 2006. A portion of the original route of the Alaska Highway, known as the Alaska-Canada Military Highway (Segment) was added to the National Register of Historic Places on July 31, 2013. You can view a contemporary documentary film about building the highway presented by C-Span.

[12] Densho 2023. From the Densho website (emphasis added): “The commonly used term “internment” fails to accurately describe what happened to Japanese Americans during WWII. “Internment” refers to the legally permissible, though morally questionable, detention of “enemy aliens” in time of war. There were approximately 8,000 Issei (“first generation”) arrested as enemy aliens and subjected to what could be described as “internment” in a separate set of camps run by the Army or Department of Justice. This term becomes a misleading, othering euphemism when applied to American citizens detained by their own government; yet two-thirds of Japanese Americans incarcerated during WWII were U.S. citizens by birth and right. Although “internment” is a recognized and widely used term, we encourage the use of “incarceration,” except in the specific case of Japanese Americans detained by the Army or DOJ. “Detention” is used interchangeably—although some argue that the word denotes a shorter period of confinement than the nearly four years the camps were in operation.”

[13] Hampton Roads Naval Museum 2012.

Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities (n.d.) “Alaska Highway 75th Anniversary.” Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities.

Bailey, Beth and David Farber (1993) “The ‘Double-V’ Campaign in World War II Hawaii: African Americans, Racial Ideology, and Federal Power.” Journal of Social History, 26(4): 817-843.

Brechin, Gray (2014) “The First Family of Radio: Voices of Destiny, The Roosevelts on the Radio.” The Living New Deal, December 24, 2014.

Cunningham, W. Scott (1962) Wake Island Command. Popular Library, New York.

Densho. (2023) “Terminology.” Densho.

Hampton Roads Naval Museum (2012) “’Because Somebody Talked!’ – 1944 Poster.” Hampton Roads Naval Museum, November 23, 2012.

History Matters (n.d.) “’This is No Joke: This is War’: A Live Radio Broadcast of the Attack on Pearl Harbor.” History Matters: The US Survey Course on the Web.

Horner, Dave (2013) The Earhart Enigma: Retracing Amelia’s Last Flight. Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna.

Jacobs, Martin (2006) “Remember Pearl Harbor.” America in WWII, December 2006.

Little, Becky (2022) “Pearl Harbor Wasn’t Japan’s Only Target.” History.com, December 5, 2022.

McDonough, John (1991) “Hear It Now: Pearl Harbor Day Radio.” Wall Street Journal, December 6, 1991 p. A13.

National Park Service (2018) “Civilian Casualties” [Pearl Harbor]. National Park Service, November 14, 2018.

Palomo, Tony (1994) “Rising Sun Dawns on Guam.” In Golden Salute Committee (ed.), Liberation – Guam Remembers: A Golden Salute for the 50th Anniversary of the Liberation of Guam. Guam.

Palomo, Tony and Katherine Aguon (2023) “WWII: From Occupation to Liberation.” Guampedia, January 7, 2023.

Patel, Samir S. (2017) “A Timeline of the Attack.” Archaeology Magazine, January/February 2017.

Roosevelt, Eleanor (1941) “Radio Address, December 7, 1941 (Attack on Pearl Harbor).” Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project.

Roosevelt, Franklin D. (1941) “Joint Address to Congress Leading to a Declaration of War Against Japan (1941)” [December 8 1941]. Milestone Documents, National Archives and Records Administration.

Rottman, Gordon L. (2004) Guam 1941 & 1944: Loss and Reconquest. Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK.

Scheiber, Harry N. and Jane L. Scheiber (2020) “Martial Law in Hawai’i.” Densho Encyclopedia, July 22, 2020.

--- (2016) Bayonets in Paradise: Martial Law in Hawai’i during World War II. University of Hawai’i Press, Honolulu.

Smith, Stephen (2014) “Eleanor Roosevelt: The First Lady of Radio.” The First Family of Radio: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt’s Historic Broadcasts, APMReports, November 10, 2014.

Tassava, Christopher J. (2008) “The American Economy During World War II.” EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples, February 10, 2008.

United States Congress (1940) “Public Law 76-783. An Act to Provide for the Common Defense by Increasing the Personnel of the Armed Forces of the United States and Providing for its Training.” United States Congress, September 16, 1940, pp. 885-897.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

-

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan Orosa

The Home Front During World War IIMaria Ylagan OrosaMaria is best known as the inventor of banana ketchup. Her impact on Philippine life and her heroism on the home front is much greater.

-

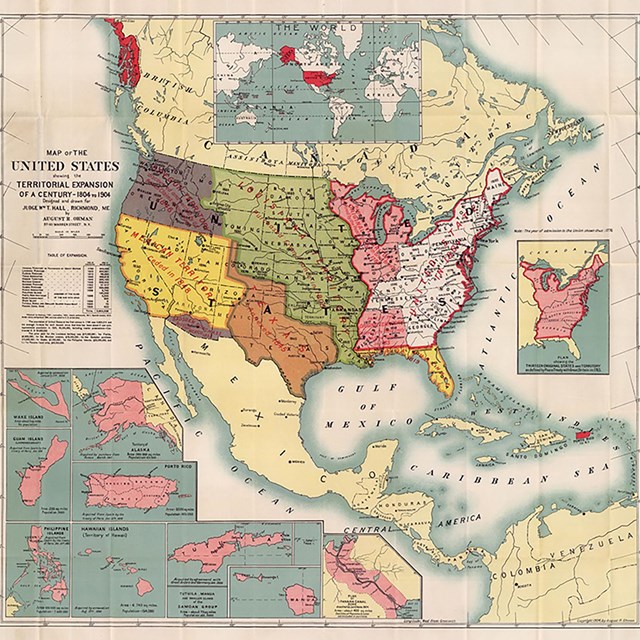

The Home Front Before World War IIThe Greater United States

The Home Front Before World War IIThe Greater United StatesTo understand the geography of the American home front in World War II, we need to go back as far as the middle of the 1800s.

-

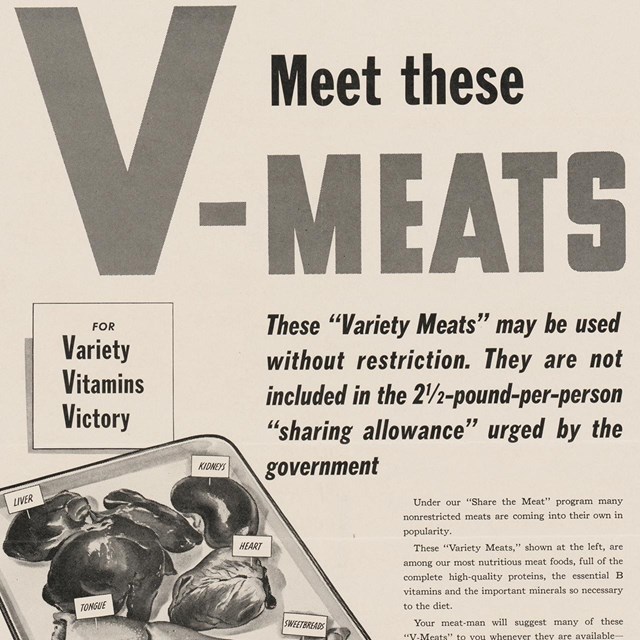

The Home Front During World War IIMeat Rationing

The Home Front During World War IIMeat RationingMeat was on the ration list from March 1943 through November 1945, spurring Meatless Tuesdays, a thriving black market, and new recipes.

Tags

- world war ii

- world war 2

- wwii

- world war ii home front

- homefront

- home front

- military history

- japan

- hawaii

- guam

- howland island

- midway

- wake island

- philippines

- transportation history

- prisoners of war

- pow

- science and technology

- virginia

- economic history

- migration and immigration

- labor history

- african american history

- asian american and pacific islander history

- government history

- national historic landmark

- national register of historic places

- american world war ii heritage city

- awwiihc

- manitowoc

- wisconsin

- incarceration

- internment