Last updated: November 16, 2023

Article

Introduction to Life on the World War II Home Front in the Greater United States

Collection of Northwestern University Libraries, Government & Geographic Information Collection (ark:/81985/n2bg2kb9x).

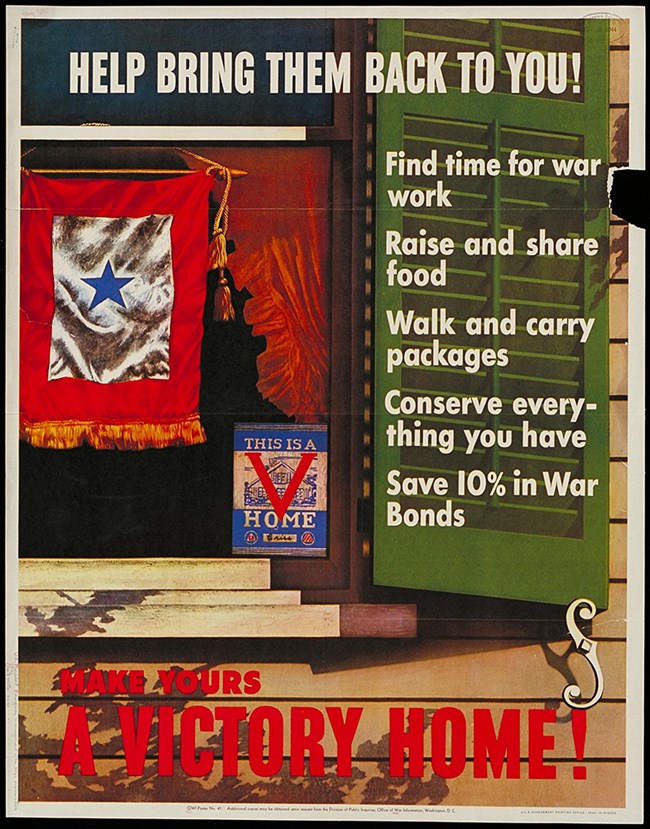

What was it like to live on the World War II home front in the mainland United States and its territories? The war was an all-out effort, calling on civilians to do their part to support the military effort. That war may seem like it happened long ago, but the innovations and sacrifices still affect our lives today.

The United States’ involvement in World War II did not occur only on foreign soil and in foreign waters and foreign skies. It also affected the lives of Americans on the home front. Much of this impact was associated with mobilizing for the war. People moved to new places across the country to work and to train and their lives changed. Factories re-tooled and ran around the clock to produce weapons and other military supplies. Whole new industrial centers sprung up across the country, often including worker housing. Goods like cars, toys, and fridges disappeared from the market. Even doctors and nurses became scarce. The government rationed other goods like some foods and gasoline. People across the country grew their own food and collected needed materials to support the war.[1] This set of articles explores the American places and people on the home front affected by World War II.

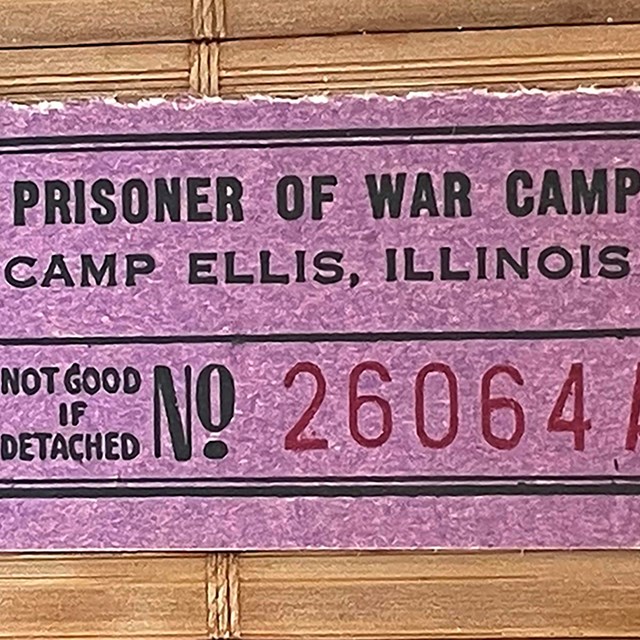

Most studies of the home front focus on mobilization efforts within the continental United States. Indeed, this was the focus of the US government during the war. And it has served as the popular memory of the war – a clean division between war “over there” and the home front “over here" (except for the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawai’i, which was not yet a state.) [2] But Americans at home also experienced conflict. Civilians watched for enemy aircraft and kept their lights off at night. Enemy submarines patrolled American waters. Enemies attacked and sometimes captured parts of the US, killing American civilians. Death and destruction accompanied the takeovers and the later liberation by US forces. Spies on American soil sent secrets to their enemy handlers. The war also shaped the home front as the US government incarcerated hundreds of thousands of people. These included Americans of Japanese, Italian, and German descent, Alaska Natives, and prisoners of war.

These articles explore life on the home front by looking at the things people invented, created, and used and the ways that everyday life changed. They include the effects of war mobilization and of conflict on the home front, especially as it relates to civilians. While the US did not formally enter World War II until December 1941, buildup and war in Europe and increasing tensions in the Pacific affected Americans at home. These articles focus on the full extent of World War II, from 1939 to 1945. They also look at (though not as in depth) the years leading up to the war and the effects of World War II on the home front after 1945.

Collection of the David Rumsey Map Collection, Stanford University Libraries (2087.002).

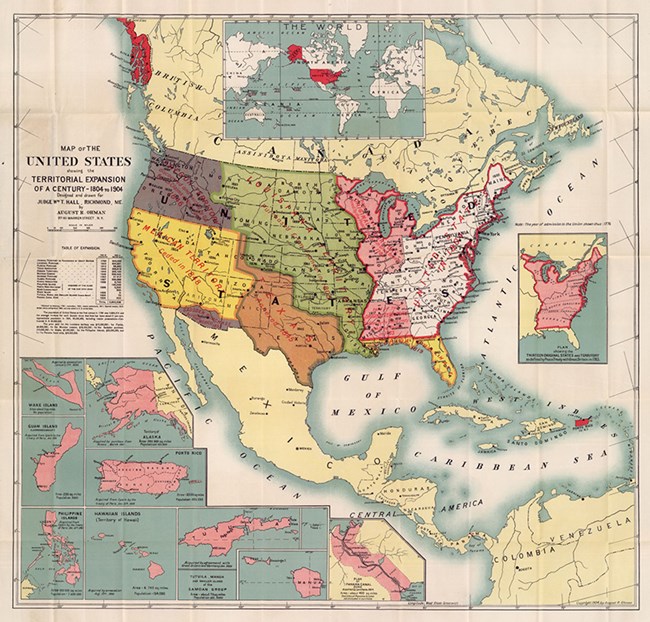

Defining the Home Front: Geography

When World War II started in 1939, the United States was made up of 48 states plus several jurisdictions (territories and possessions). It was also home to many Indigenous groups. Some of these were federally recognized tribes with a special government-to-government relationship with the US government, based on treaties and other agreements. A few of the US jurisdictions were military-only, but in most, civilians lived, worked, and played. [3] Some of these places had been under US jurisdiction and colonization since the mid-1800s; others more recently. By the end of the war, the United States had lost some of these territories and possessions, and gained others. [4]

The military, media, and the general public often treated the US territories and possessions as foreign soil. This kind of thinking excludes those who lived there and the war on their doorsteps from discussions of the home front. Why did people think differently about these places? It may have been the “newness” of these places to US jurisdiction or an extension of the American isolationist trend that followed World War I. It may have also been part of the desire for America to appear as an anti-colonial force on the world stage; or the “foreign-ness” of the various cultures, languages, and environments in these places. As well, in the early 1900s, the US Supreme Court determined that the Constitution did not apply to these places. [5] They were not, however, “geographical crumbs” [6] -- though many of them were small in size. Almost 19 million people – 12.2% of the US population -- lived in these US jurisdictions in 1940. [7]

From as early as 1904, writers have used the term “Greater United States” to include these areas. This is a useful concept when considering the home front. Indeed, many early 1900s maps included these places as part of the US -- a practice that had largely disappeared by World War I. [8]

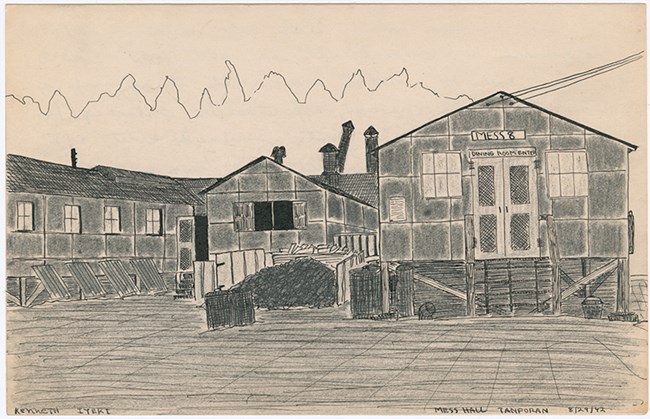

Evidence and Absence: How Do We Know What We Know?

Collection of the Spurlock Museum of World Cultures, University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (1944.03.0021).

Many different sources provide information about the material culture of the home front. Things that can be touched and experienced include the items and objects from the time, but also the built environment and landscapes. Photographs, newspapers, magazines, films, posters, and other archival materials --themselves objects -- provide images and descriptions. Researchers can glean information from letters, oral histories, and other first-person accounts. Museums and archives, archaeological sites, and the built environment provide sources of information. Studies that look at the broader histories of World War II help to place these sources into context.

Collection of Densho, Kenneth Nobuji Iyeki Collection (ddr-densho-392-26).

This article was written by Megan E. Springate, Assistant Research Professor, Department of Anthropology, University of Maryland, for the NPS Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

[2] Immerwahr 2016: 387.

[3] Neither Alaska nor Hawaii were yet states.

[4] In the Pacific, these were Alaska Territory; American Samoa; Baker Island; Canton Island; the Commonwealth of the Philippines; Enderbury Island; Guam; Hawai’i Territory; Howland Island; Jarvis Island; Johnston Atoll; Midway Atoll; Palmyra Atoll; and Wake Island. In the Atlantic, these were Puerto Rico, the Swan Islands, and the US Virgin Islands. The Panama Canal Zone, controlled by the US, connected the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. Also considered are the new territories that came under the umbrella of the Greater United States as a result of World War II, including the Amami and Tokara Islands (Northern Ryukyu Islands), Daitō Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Kazan-Retto (Volcano Islands), Marshall Islands, Minamitorishima (Marcus Island), Nansei Shoto (Ryukyu Islands), Nishinoshima (Rosario Island), Northern Mariana Islands, Ogasawara-Gunto (Bonin Islands), Okinotorishima (Parece Vela), Palau, and Water Island. Of these, only the Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, Palau, and Water Island retain their jurisdictional connections to the United States.

[5] Immerwahr 2016: 381.

[6] Neil Smith, American Empire, in Immerwahr 2016: 376.

[7] Immerwahr 2016: 376-377.

[8] Immerwahr 2016: 381.

[9] Gaskell and Carter 2020; Mayo 1980; Shrum 2019. See, for example, Seaver 2018 and Swader 2015.

[10] Harper 2007: 1; emphasis mine.

[11] Petrov 2012: 226, 229, 231. These vary based on what kind of museum or archive it is – for example, an art museum will focus their collection on different items than an historical museum will; and an archive focused on a particular region will be very different from a one focused on a particular event or time period. Even when these institutions might collect the same items, how they are described and interpreted will be different. Archaeology is very good at providing information on the everyday lives of people – things often not otherwise recorded in written documents or collected by museums. Archaeology is not good, however, in revealing information about the lives of individual people. And it relies on what is left behind when people move on. Just as museums and archives are selective in what they consider important to collect and interpret, there have been limitations to the archaeology of World War II on the home front. In the United States, a lot of archaeology is done to comply with various permitting requirements for construction and development. This helps ensure that important historic resources can be avoided or recorded. The criteria established by the National Register of Historic Places are used to decide if the resource (site, building, structure, landscape, district) is significant. This includes a stipulation that, except in exceptional circumstances, properties must be over 50 years old to be considered (Stiles 2010). It was not until 1995 (50 years after the end of the war), then, that archaeological sites from the period were often even considered; and even then, mid-century homes, businesses, and other places associated with the home front were not always excavated due to being too recent.

[12] Lawrence 2017.

[13] For more information on mealtimes for incarcerated Japanese Americans in War Relocation Centers, see Hinnershitz 2022.

Gaskell, Ivan and Sarah Anne Carter (2020) “Introduction: Why History and Material Culture?” In Ivan Gaskell and Sarah Anne Carter (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture, Oxford University Press, pp. 1-13.

Harper, Marilyn (2007) World War II & The American Home Front: A National Historic Landmark Theme Study. National Park Service, Washington, DC.

Hinnershitz, Stephanie (2022) “Lunchbox Lecture: Mealtime in the Mass Halls: Food in the Japanese American Incarceration Camps of World War II.” National World War II Museum, August 3, 2022.

Immerwahr, Daniel (2016) “Bernath Lecture: The Greater United States: Territory and Empire in U.S. History.” Diplomatic History 40(3): 373-391.

Lawrence, Kerri (2017) “Correcting the Record on Dorothea Lange’s Japanese Internment Photos.” National Archives News, February 16, 2017.

Mayo, Edith (1980) “Introduction: Focus on Material Culture.” The Journal of American Culture 3(4): 595-604.

Petrov, Julia (2012) “Cross-Purposes: Museum Display and Material Culture.” Cross-Currents 62(2): 219-234.

Seaver, James B. (2018) “Fighting for Souvenirs: Americans and the Material Culture of World War II.” PhD dissertation, Department of History, Indiana University.

Shrum, Rebecca (2019) “Material Culture.” The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook, June 3, 2019.

Stiles, Elaine (2010) “50 Years Reconsidered.” Forum Journal & Forum Focus, National Trust for Historic Preservation, Summer 2010.

Swader, Paul (2015) “An Analysis of Modified Material Culture from Amache: Investigating the Landscape of Japanese American Internment.” MA thesis, Social Sciences, University of Denver.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. The American Home Front Before World War II

3. The American Home Front and the Buildup to World War II

3B The Selective Service Act and the Arsenal of Democracy

4. The American Home Front During World War II

4A A Date That Will Live in Infamy

4A(i) Maria Ylagan Orosa

4C Incarceration and Martial Law

4D Rationing, Recycling, and Victory Gardens

4D(i) Restrictions and Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii) Food Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(a) Nutrition on the Home Front in World War II

4D(ii)(b) Coffee Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(c) Meat Rationing on the World War II Home Front

4D(ii)(d) Sugar: The First and Last Food Rationed on the World War II Home Front

4D(iii) Rationing of Non-Food Items on the World War II Home Front

4D(iv) Home Front Illicit Trade and Black Markets in World War II

4D(v) Material Drives on the World War II Home Front

4D(v)(a) Uncle Sam Needs to Borrow Your… Dog?

4D(vi) Victory Gardens on the World War II Home Front

4D(vi)(a) Canning and Food Preservation on the World War II Home Front

4E The Economy

4E(i) Currency on the World War II Home Front

4E(ii) The Servel Company in World War II & the History of Refrigeration

5. The American Home Front After World War II

5A The End of the War and Its Legacies

5A(i) Post World War II Food

More From This Series

-

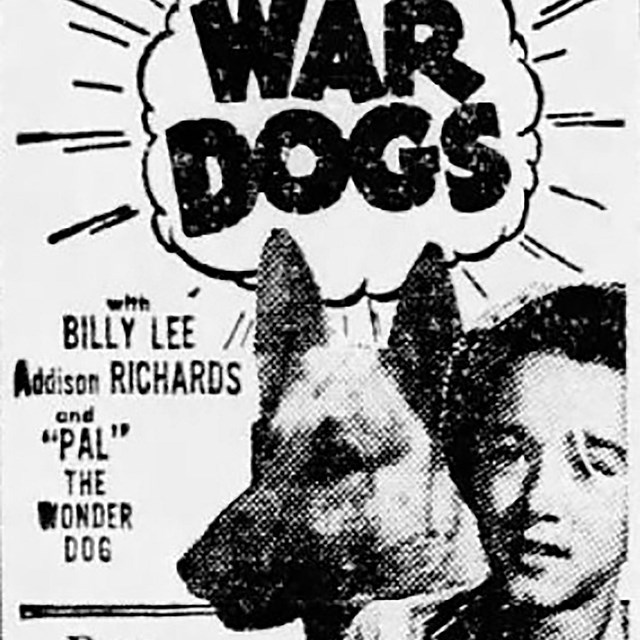

The Home Front During World War IIUncle Same Needs to Borrow Your... Dog?

The Home Front During World War IIUncle Same Needs to Borrow Your... Dog?Owners volunteered over 40,000 pet dogs for World War II service, spurred in part by the 1942 War Dogs movie.

-

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home Front

The Home Front During World War IICurrency on the World War II Home FrontPaper money and coins saw changes because of the war. New materials and new types of money reminded people every day that the US was at war.

-

The Home Front After World War IIPost World War II Food

The Home Front After World War IIPost World War II FoodWorld War II changed what and how Americans eat -- from a taste for military rations and foreign food to processed foods and candy.

Tags

- world war ii

- wwii

- wwii home front

- world war ii home front

- military history

- geography

- international relations

- history of technology

- material culture

- doing history

- preservation

- alaska

- american samoa

- philippines

- guam

- hawaii

- baker island

- howland island

- jarvis island

- johnston atoll

- midway atoll

- palmyra atoll

- wake island

- puerto rico

- us virgin islands

- panama canal zone

- panama canal

- federated states of micronesia

- marshall islands

- northern mariana islands

- palau

- us in the world community