Last updated: September 11, 2023

Article

Childcare on the World War II Home Front

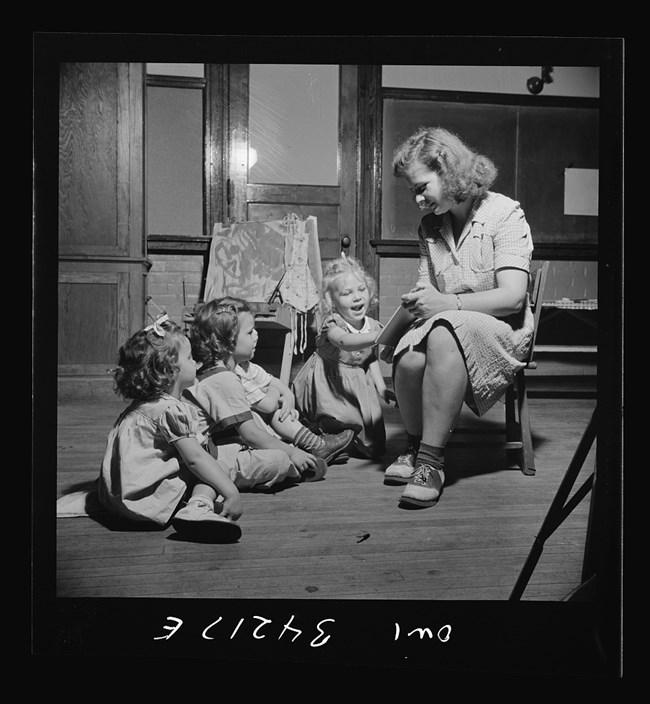

Photo by Gordon Parks, US Office of War Information, June 1943. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Introduction

The iconic image of “Rosie the Riveter” dominates memory of the American World War II home front. Indeed, millions of women took jobs in munitions factories, shipyards, and hospitals to support the war effort—and their families. Many women had husbands who had joined the military or worked long hours away from home. Others were single parents.

Overall, women headed nearly 20% of US households during the war years. But despite public praise for female workers’ patriotism, at the beginning of the war “Rosies” with young children had few options for childcare during their long shifts. While some could rely on neighbors or grandparents, many women had moved far from their support systems to take jobs in war industry boomtowns.

In 1943, Congress allocated $20 million to create the nation’s first and only universal childcare program under an infrastructure law called the Lanham Act (1940). States and private companies used the funding to set up hundreds of “war nurseries” that enrolled an estimated 550,000 children over the course of the war. Though the program was temporary and did not reach every family who needed care, it represented an important milestone: the first time the US government acknowledged childcare as critical infrastructure.

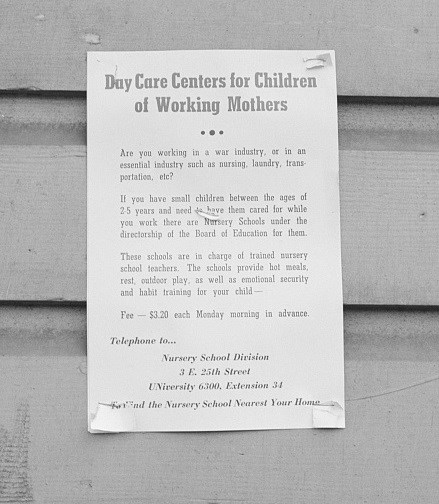

Photo by Arthur S. Siegel, United States Office of War Information, May 1943. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Childcare and the Lanham Act

As more women went to work for the war effort, the dire need for childcare became increasingly clear. Anecdotes about working women forced to leave their children home alone alarmed policymakers and the public. At the same time, public officials recognized that a lack of childcare interfered with women’s productivity. One report from Oregon noted that “women’s absenteeism in the shipyards is four to five times as great as that of men due in large part to the breakdown of plans for the care of their children.”[1] Many Americans still opposed mothers working outside the home, but labor unions and female politicians reminded Congress that if the country wanted Rosie the Riveter to help win the war, it would need to find a way to provide for her children.

In response, Congress authorized Lanham Act funds for states and cities to set up childcare centers in centers of war industry. Due to bureaucratic hurdles, expansion of the program moved slowly. It also varied considerably across states. For example, while California spent an average of $264 per child, New Mexico spent $0. Nevertheless, for many families who used them, the centers represented a welcome relief from worry about their children’s well-being while they worked to earn a living. Programs offered them meals, activities, and a safe place to spend their days and socialize with other children.

Perhaps most crucially, the centers were affordable. The cost to parents averaged about fifty to seventy-five cents per child, per day—the equivalent of about nine to fourteen dollars per day in the 2020s.

NPS Photo.

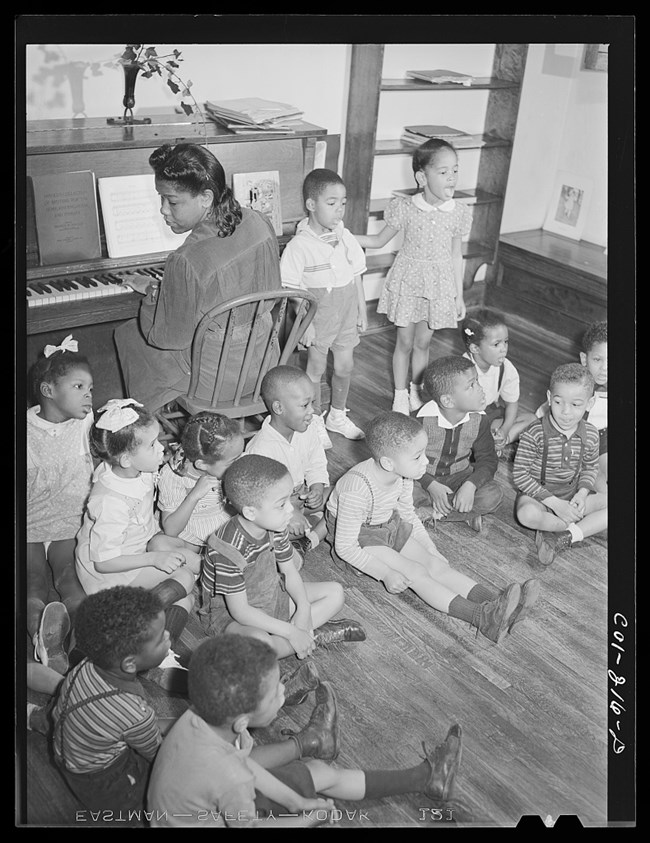

War Nurseries

Private companies also used Lanham Act funds to set up on-site childcare centers for their workers. The Kaiser Shipyards in California, Oregon, and Washington boasted some of the largest facilities. They were located right at the entrance to the shipyards so mothers could drop off and pick up their children on their way to and from their shifts.

Each center featured large outdoor play yards, wading pools, and light-filled classrooms, and each employed teachers, a nurse, a dietician, and a social worker. “Everything was new, we had the best of equipment and lots of it,” recalled Jean E. Amonson, a teacher at the Kaiser center in Portland, OR. “We had library books, crayons, papers, and blocks…the children played with those by the hour.”[2]

Kaiser centers even offered “Home Service Food,” a nutrition program promoted by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt that offered hot dinners that women could pick up when they came for their children.

Photo by Arthur Rothstein, US Office of War Information, March 1942. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Postwar Legacy

After the end of the war in 1945, factories laid off hundreds of thousands of women workers to give their jobs to returning men. Most employed women, though, fully intended to keep working—by necessity, choice, or both. Their daycare needs had not disappeared with the coming of peacetime. Many of them organized to demand that childcare programs continue. At one picket in New York City, a group of women and children held signs declaring “While We Work Our Children Must Be Safe” and “Food Prices Rise—Mothers Must Work.”[3]

However, Congress failed to extend funding. Only New York, California, and Washington planned for partial extensions of the programs, and even these arrangements ran out after a few more years. Without federal aid, childcare became scarcer and much more expensive. Women and families continued to struggle to balance the demands of breadwinning and caretaking in ways that continue into the 21st century.

Notes

[1] "Annual Report 1942-1943," Council of Social Agencies, Portland Oregon, 1944. Page 7, Folder 7, Box 25, Defense Council Records, OSA. Quoted in “With Mother at the Factory…Oregon’s Child Care Challenges.” In Life in the Home Front: Oregon Responds to World War II, Oregon Secretary of State, https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/ww2/Pages/services-child-care.aspx

[2] Interview with Jean E. Amonson, by Karen Beck Skold, Feb. 13, 1976, 4.

[3] Lydia Kiesling, “Paid Child Care for Working Mothers? All It Took Was a World War,” New York Times, Oct. 2, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/us/paid-childcare-working-mothers-wwii.html.

Sources

Amonson, Jean E. Oral History Interview. By Karen Beck Skold. Women Workers and Childcare during World War II, Mss 1803, Karen Beck Skold Research Papers, Oregon Historical Society. February 13, 1976. https://digitalcollections.ohs.org/sr-1677-interview-with-jean-e-amonson.

Enoch, Jessica. “There’s No Place Like the Childcare Center: A Feminist Analysis of in the World War II Era.” Rhetoric Review 31, no. 4 (2012): 422–42.

Herbst, Chris M. “Universal Child Care, Maternal Employment, and Children’s Long-Run Outcomes: Evidence from the US Lanham Act of 1940.” Journal of Labor Economics 35, no. 2 (2017): 519–64.

Kiesling, Lydia. “Paid Child Care for Working Mothers? All It Took Was a World War.” The New York Times, October 2, 2019, sec. U.S. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/02/us/paid-childcare-working-mothers-wwii.html.

Tuttle, William M. “Rosie the Riveter and Her Latchkey Children: What Americans Can Learn About Child Day Care from the Second World War.” Child Welfare 74, no. 1 (1995): 92–114.

Koshuk, Ruth Pearson. “Developmental Records of 500 Nursery School Children.” The Journal of Experimental Education 16, no. 2 (1947): 134–48.

Article by Ella Wagner, PhD, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Article by Ella Wagner, PhD, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

Tags

- rosie the riveter wwii home front national historical park

- women's history

- world war ii

- wwii

- world war ii home front

- wwii home front

- shaping the political landscape

- labor history

- gender

- childcare

- military history

- rosie the riveter

- rosie the riveter / wwii home front national historic park

- women workers

- children

- education

- education history

- california

- oregon

- washington state

- awwiihc criteria