Mount Rainier is a national park because people with very different points of view came together to save a magnificent landscape from being forever lost. Businessmen, scientists, teachers, mountain climbers and ecologists united their efforts to lobby Congress for six years to protect Mount Rainier as a national park. Their efforts were rewarded when President McKinley signed legislation on March 2, 1899, making Mount Rainier the fifth national park. Their reasoning was so convincing that many of their arguments are included in the park's significance statements. A park's significance statements are the unique reasons identifying why a park exists. They, along with a park's mission and purpose, form the basis for every aspect of the park's management. Listed below are the significance statements for Mount Rainier National Park.

Mount Rainier and its associated geologic and glacial featuresAt a height of 14,410 feet, Mount Rainier is the highest volcanic peak in the contiguous United States. It has the largest alpine glacial system outside of Alaska and the world's largest volcanic glacier cave system (in the summit crater). Visible throughout the region, Mount Rainier shapes the physical environment, inspires the human experience, and defines the identity of the Pacific Northwest.

Photo by Tiffany Von Arnim, used with permission under a Creative Commons license. An active volcanoAs part of the Pacific Ring of Fire, Mount Rainier is an outstanding example of Cascade volcanism. Mount Rainier's eruptions and mud flows have shaped the area and future eruptions are a potential threat to park visitors, employees, infrastructure, and surrounding lowland communities. Mount Rainier is the second most seismically active and the most hazardous volcano in the Cascade Range. It is extensively monitored by the U.S. Geological Survey to provide advance warning of future eruptions.

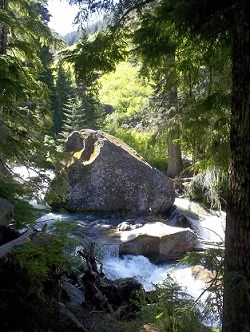

NPS Photo Source of water for the Puget Sound regionMount Rainier National Park protects the headwaters of five major watersheds that originate on the mountain's glaciers and are an important source of water for the Puget Sound region. Mount Rainier reaches up into the atmosphere to disturb great tides of eastward moving Pacific maritime air, resulting in spectacular cloud formations, prodigious amounts of rain, and record-setting snowfalls.

NPS Photo Subalpine and alpine ecological communities of flora and faunaMount Rainier National Park is a vital remnant of the once widespread primeval Cascade ecosystem and provides habitat for many species representative of the region’s flora and fauna. The park preserves a diverse mosaic of subalpine and alpine ecological communities and contains outstanding examples of diverse vegetation communities and dependent organisms, ranging from old-growth forest to subalpine meadows and ancient heather communities.

NPS Photo Mount Rainier is 97% wildernessMount Rainier National Park protects more than 97% of its area as federally designated wilderness. Particularly as urban and rural development expands, the park increases in importance to the region, the nation, and the world as a large island of protected open space where ecosystem processes dominate and opportunities for wilderness recreation, including solitude, are available to a growing and diverse population.

Enjoy but preserveWilderness allows us to experience natural environments unchanged by humans. But experiencing wilderness without altering it requires care and knowledge. "Leave No Trace" techniques help us to minimize our impact on wilderness areas as we enjoy them. Wildlife encountersIt is thrilling to see animals in the wild, and it's important to know what to do or not to do when you encounter wildlife.

NPS photo More than 9,000 years of human presence at Mount RainierMount Rainier National Park contains an extensive archeological record demonstrating more than 9,000 years of human connection to the mountain. The resources of the park continue to provide material, spiritual, and cultural sustenance to contemporary descendent tribes, including the Cowlitz, Muckleshoot, Nisqually, Puyallup, Squaxin, and Yakama.

NPS Photo Original model of architectural style for National ParksThe developed areas of Mount Rainier contain some of the nation’s best examples of intact "National Park Service Rustic" style architecture and naturalistic landscape architecture of the 1920s and 1930s. The Mount Rainier National Historic Landmark District is considered to be the most complete and best preserved example of NPS master planning in the first half of the 20th century.

NPS photo The park is a wilderness laboratory for study and researchMount Rainier is a living laboratory that offers opportunities for scientists and students to study and develop a deeper understanding of as well as foster an appreciation for the park, its resources, processes, and meanings. Due to its great elevation range and extensive glacial systems, Mount Rainier’s geology, hydrology, ecological communities, and historic infrastructure are acutely sensitive to climate change impacts, offering an exceptional opportunity to observe and understand the effects of climate change and demonstrate climate change response in the national park system. Research conducted at Mount Rainier

NPS Photo World class recreation and trainingMount Rainier offers recreational and educational opportunities in a wide range of scenic settings, including wildflower meadows, glaciers, and old growth forests, all in a relatively compact area that is easily accessed by a large urban population. The park's terrain and weather conditions offer world-class climbing opportunities that have tested the skills of climbers for more than a century. Recreational and educational opportunities Quest for the summitClimbing information |

Last updated: January 28, 2025