Part of a series of articles titled A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women’s Rights Movement.

Article

A Great Inheritance: The Abolition Movement and the First Women's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls

This article is part of a series, "A Great Inheritance: Examining the Relationship between Abolition and the Women's Rights Movement" written by Victoria Elliott, a Cultural Resources Diversity Internship Program (CRDIP) intern at Women's Rights National Historical Park.

The Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention is regarded as the first women’s rights convention and the beginning of the women’s rights movement. The organizers of the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls- Lucretia Mott, Martha Coffin Wright, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Jane Hunt, and Mary Ann M’Clintock- were neighbors, friends, and relatives who decided to arrange the convention over their shared convictions. However, prior to the first women’s rights convention, the only woman in the group with public speaking experience was Lucretia Mott. While the other four organizers lacked public speaking skills, they each had backgrounds in the abolitionist movement and were dedicated to the anti-slavery cause which prepared them to organize the first women’s rights convention.

By 1848, Lucretia Mott was well-established as a leader within the abolition movement. From her participation at the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) founding convention she engaged in activities to support the anti-slavery movement and was a founding member of the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society. Lucretia Mott wrote and spoke publicly for anti-slavery. As a Quaker minister, Mott began preaching at Meetings but travelled extensively throughout the North as a speaker for abolition and other reform causes by the 1840s.[68]

Martha Coffin Wright, sister to Lucretia Mott, lived in the city of Auburn, New York at the time of the 1848 Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention. Like her sister, Martha Wright was involved in the establishment of the Philadelphia Female Anti Slavery Society.[69] The kitchen of her Auburn home was used by freedom seekers on the Auburn Underground Railroad. She travelled to and attended American Anti-Slavery Society meetings, held leadership positions, and contributed to anti-slavery fairs.[70]

Jane Hunt and her husband Richard were Hicksite Quakers who involved themselves with many reform activities for the abolition and temperance movements.[71] The Hunts were especially dedicated to equality and belonged to radical Quaker group known as the Congregational, or Progressive Quakers, who believed in the equality of all people regardless of “sex, creed, or color.”[72] The Hunt’s house in Waterloo, New York, was also a stop on the Underground Railroad. As the lady of the house, Jane Hunt was “primarily responsible for overseeing the food and lodging needed for these freedom seekers."[73]

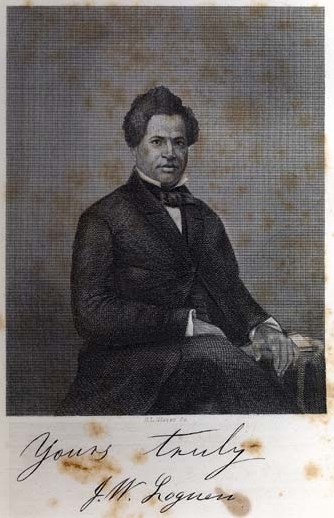

Public domain. (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jermain_Wesley_Loguen_(engraving).png)

Elizabeth Cady Stanton became an abolitionist after meeting and hearing the story of Harriet Powell, a fugitive slave staying at her cousin Gerrit Smith’s home in Peterboro, New York.[79] Stanton reflected upon this interaction, writing: “We needed no further education to make us earnest abolitionists.”[80] After attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention in 1840, Elizabeth Cady Stanton began teaching Sunday school to African American children in Johnstown, New York. She became more involved in the anti-slavery cause following the Seneca Falls Women’s Rights Convention, participating in organizations that addressed issues like temperance, women’s rights, and abolition.[81]

These women and their activities were part of state-wide abolitionist networks in Seneca Falls, Auburn, and Rochester, New York. Rochester was an Erie Canal boomtown and major reform city in New York in the 19th century.[82] During this period the city was undergoing many changes from industrialization to the entrance of new immigrants and laborers.[83] Rochester changed from the Flour City to the Flower City as singular grain mills transformed into a diverse range of factories, nurseries, foundries and mills. The area was also a part of the “Burned Over District,” and was affected by waves of religious change and the emergence of new religious groups. Rochester was home to communities of free African Americans, Quakers, and Evangelical Christians, and the city was open to and fostered radical reform movements. Most Rochesterians were not active supporters such movements, but the practices were largely tolerated.[85]

Rochester was home to many prominent abolitionists, reform leaders, and agents for the Underground Railroad. The foremost Rochesterian names associated with the antislavery cause include Frederick Douglass, Susan Brownell Anthony, Isaac and Amy Post, and William Bloss. Other agents of the city’s Underground Railroad were members of the Rochester Anti-Slavery Society. Famous Rochester sites associated with the Underground Railroad include William Bloss’ home, Samuel Porter’s barn, and the African Methodist Episcopal Zion church of Reverend Thomas James.[88]

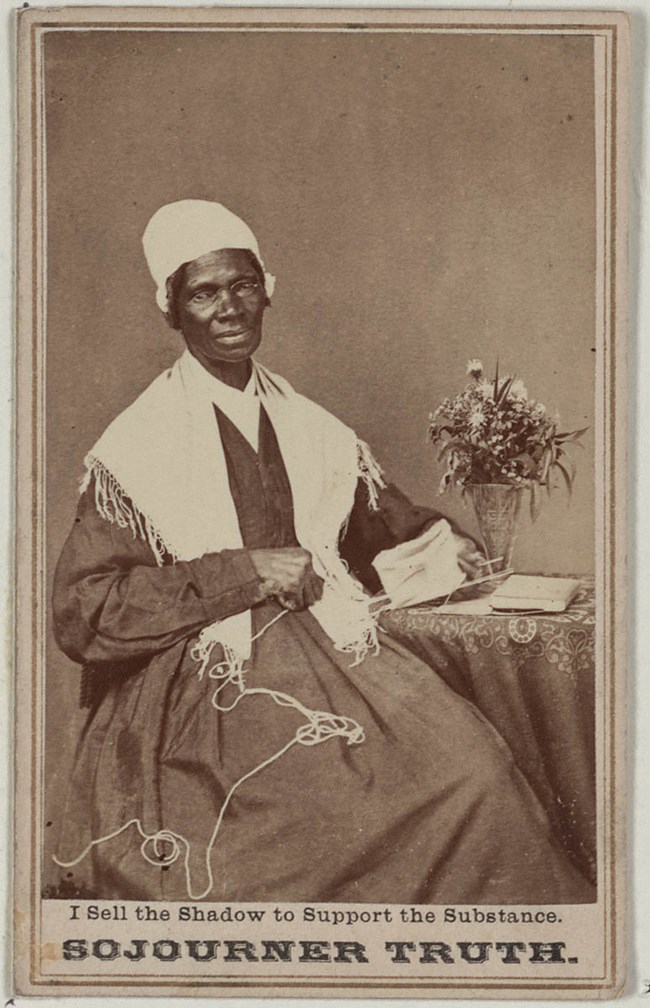

Isaac and Amy Kirby Post were some of the most prominent Rochester reformers. The Posts were Quakers who earned their living through farming and a pharmacy. Their home at 36 Sophia Street provided shelter to freedom seekers, and at one time held at least 20 fugitive slaves. Harriet Ann Jacobs, author of the autobiography titled Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861), lived at the Post residence for a year.[89] Their involvement in such activities would eventually force them to leave the Society of Friends. The Posts were intimately and nationally connected to other members of the abolitionist movement such as Abby Kelley Foster, William Lloyd Garrison, Sojourner Truth, and fellow Rochesterian Frederick Douglass.

When Frederick Douglass returned to the United States from England in 1847 to start his own anti-slavery newspaper, the North Star, he faced the problem of determining where to base his operation. His anti-slavery newspaper needed to be set away from competitors like William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator in Boston and the New York City anti-slavery paper the National Anti-Slavery Standard.[90] It was in Rochester that Douglass decided to begin his endeavor and from Rochester that he continued his work in the fight against slavery. Like his fellow radical Rochesterians, Frederick Douglass was an agent on the Underground Railroad.

The Underground Railroad flourished in Auburn due to varying networks of support. According to a 2005 survey of Auburn and Cayuga County, Auburn Underground Railroad supporters and sympathizers can be grouped into four distinct communities: African Americans, Quakers, politicians, and religious abolitionists.[92] Each of these groups were well-connected. Take, for example, Nicholas and Harriet Bogart. They were former northern slaves who settled in Auburn and came under the employment of the Seward family, whose home was a stop on the Underground Railroad. Through these relationships, the Bogarts were able to connect freedom seekers to Underground Railroad agents in both African American and European American communities.[93] Auburn abolitionist Quakers were also active agents in the abolitionist and Underground Railroad communities.[94] These Auburn Quakers were connected to abolitionists in other states like Pennsylvania and Delaware in addition to prominent local lawyers, politicians, and professionals who organized important anti-slavery work in the area.[95] Auburn churches were also important sources of abolitionist activity in Cayuga County, providing aid to Canada-bound freedom seekers and finding employment for those who chose to make Auburn the last stop on their journey out of slavery.[96]

Frances and William Henry Seward were devoted abolitionists and reformers whose affiliations connected them to Quaker groups, African American communities, and Auburn politicians. William Henry Seward moved to Auburn following his marriage to Frances Miller. William Seward, trained as a lawyer, became involved in state politics in the 1830s and was nationally known as an abolitionist. In a private capacity Seward served as the defense lawyer in the murder trial of William Freeman, an African American and Native American Auburn native who suffered from mental illness. Seward was one of the first lawyers to argue the “insanity defense” in the United States. He returned to politics in 1849 and used his political career to support the abolitionist cause.[97]

While her husband was engaged with political matters in the fight against slavery, Frances Seward also contributed to the abolition movement through her active work with the Auburn Underground Railroad. Frances, who remained in their Auburn home while William Henry Seward was busy with politics in Washington, was responsible for the couple’s support of the Underground Railroad. Their home was more than a stop on the Freedom Trail.

Frances Seward also provided African Americans with financial assistance and concerned herself with the educational advancement of freedom seekers in her home.[98] Several African American children who resided at the Seward home were provided an education via Frances’ financial assistance. Both Frances and her husband were well established with local abolitionist networks, and consistently acted as patrons of Harriet Tubman and her family during her time in Auburn and helped raise Harriet Tubman’s niece, Margaret Stewart.[99]

Harriet Tubman came to Auburn around 1857 or 1858. In 1859, she purchased land from then U.S. Senator William Henry Seward. As a fugitive slave and black woman, she technically had no legal rights according to the Dred Scott decision of 1857, but Seward made the transaction anyway. That same year Harriet Tubman moved her family from Canada into her Auburn home. By the mid 1860s, the house held twelve people, nearly all freedom seekers.[100] Following her own escape from slavery, Harriet Tubman became one of the most famous conductors of the Underground Railroad.

Martha and her husband David Wright were likewise linked to the local network of abolitionists and Underground Railroad supporters in Auburn. Martha was close friends with Frances Seward and Frances Seward’s sister, Lazette Worden, who all shared Quaker values and supported abolition and women’s rights. Martha Wright also appears to have had a relationship with Harriet Tubman. Following a long and dangerous trip from Maryland, Harriet Tubman and her refugees reached Auburn. Martha Wright wrote her daughter of the freedom seekers’ success: “expending our sympathies, as well as congratulations on seven newly arrived slaves that Harriet Tubman has just pioneered.”[101] The Wright home was a stop on the Auburn Underground Railroad since as early as 1843. Martha and her husband otherwise supported freedom seekers with clothing and financial assistance.[102]

Organized anti-slavery activities of Seneca County formally began with the formation of the Seneca County Anti-Slavery Society in 1837. At this meeting the anti-slavery supporters in Seneca Falls and neighboring town Waterloo met in joint support of the cause.[105] In 1838 Seneca County residents displayed their commitment to the anti-slavery movement through anti-slavery petitions. In this year at least eighteen petitions were sent from Seneca County to Congress with over 1300 different signatures.[106]

Many figures in Seneca Falls, like the Hunts and the M’Clintocks, were personally connected to the state-wide and national abolition societies and individuals. In 1843 Thomas M’Clintock was elected manager of the AASS; in 1840 he and Richard Hunt gifted woolen cloth to William Lloyd Garrison so that he could have a suit untainted by slave labor to wear to the 1840 World Anti-Slavery Convention in London. When the AASS sent twenty agents to speak for abolition in 1842, national figures Abby Kelley and William Lloyd Garrison traveled to Seneca Falls and Waterloo. Garrison resided in the M’Clintock home during his stay in Seneca Falls. In 1843 Elizabeth M’Clintock and Rhoda Bement of Waterloo and Seneca Falls, respectively, held an antislavery fair. The fair was supplied with local goods as well as materials from anti-slavery societies in cities like Rochester and Syracuse.[107]

Seneca Falls and Waterloo were stops on the Underground Railroad. Underground Railroad sites in Seneca Falls include the homes of probable freedom seekers Thomas James and Joshua Wright, and the Wesleyan Chapel. In Waterloo the Hunt and M’Clintock houses functioned as stations on the Underground Railroad.[108]

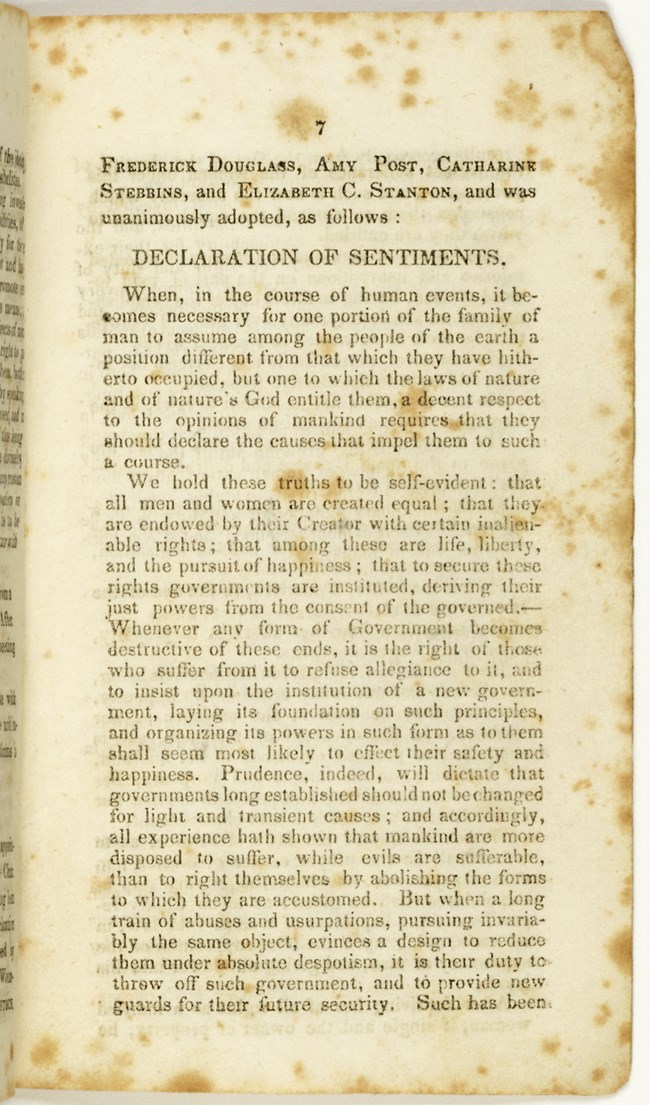

Abolitionist networks and sentiments were essential for the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls. This convention was organized and attended by abolitionists from Seneca Falls, Rochester, and Auburn. As previously explored, each of the organizers of the 1848 convention were involved with the cause of anti-slavery. Additionally, those who signed the Declaration of Sentiments, the document written for the first women’s rights convention that called out gender inequality, were also abolitionists. According to historian Judith Wellman, in addition to family ties and religious affiliations, the third central common trait found between the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments was their support of the anti-slavery movement.[110] These antislavery affiliations were reflected by the signer’s activities within political and religious groups.

As maintained by Judith Wellman’s study on the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments, the document was signed by twenty Seneca Falls residents who were either directly involved in the organization of or associated with the Free Soil Party. The Free Soil Party was a political group interested in ensuring that slavery would not be legal in western territories following the Mexican War. In the summer of 1848, this organization held a meeting in Seneca Falls. This meeting was attended by “virtually all voters in Seneca Falls.”[111] Other Seneca Falls residents were indicated as supporters of abolitionism through their recorded attendance of antislavery lectures and through subscriptions to abolitionist newspapers like the North Star.[112] The final group of non-political abolitionist signers were Hicksite Quakers. Many had subscriptions to the Liberator and lent their names to anti-slavery petitions sent to Congress in the 1830s. Quaker signers from Waterloo were also involved with the running of the Underground Railroad in Western New York. [113]

These groups were connected by their belief in equality. The values of these groups were radical for their time, as was the idea of women’s rights as presented by the convention. It follows that these individuals who already supported one radical cause in the name of equality would lend themselves to another. In total, 70% of the signers of the Declaration of Sentiments were involved in the cause of anti-slavery.[114] Abolitionists proved themselves major supporters of the women’s rights movement from its inception.

Another connection to abolition at the first women’s rights convention was the building in which the convention took place. The Wesleyan Methodist Chapel in Seneca Falls was completed in 1843. The Wesleyan Methodists formed as the Methodist church split over the issue of slavery. When the national Methodist leaders chose to ignore that southern branches of their church endorsed slavery, Seneca Falls Methodists decided to separate and form the Wesleyan Methodist Church. This Church was the most liberal of all the churches in Seneca Falls. They supported the immediate emancipation of slaves, women’s rights, and temperance. The Church also regularly opened its doors to abolitionists and reform groups and was a free meeting place, marking it as the ideal location for the first women’s rights convention. When Abby Kelley previously travelled to Seneca Falls to speak against slavery, all public meeting places were closed to her. She instead gave her speech in an apple orchard. The existence of a building in which the discussion of women’s rights could take place was dependent on the presence of abolitionists in Seneca Falls.[115]

Much is owed to the abolition movement in establishing the women’s rights movement. The ideas and values promoted by abolition supported women’s departure from their prescribed “women’s sphere.” The practices of female anti slavery societies offered opportunities for women to form communities, take on leadership roles, and engage with issues publicly and politically. Women abolitionists’ participation in public speaking to promiscuous audiences established precedence for later women’s rights activists. The abolition movement provided networks of support, and taught methods of agitation and defense against oppression and violence. The radical practices of the abolition movement provided an environment conducive to the formation of the likewise radical women’s rights movement.

Notes:

[68] Faulkner, Carol. Lucretia Mott's Heresy: Abolition and Women's Rights in Nineteenth-Century America. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011, pp. 55-60. Williams, pp. 61-78.

[69] Penney, Sherry H. and James D. Livingston. A Very Dangerous Woman: Martha Wright and Women’s Rights. University of Massachusetts Press, 2004, pp. 68.

[70] Penney and Livingston, pp. 126-128.

[71] Weber, Sandra S. “Special History Study: Women's Rights National Historical Park.” NPS Special History Study. National Park Service. Washington, D.C. 1985, pp. 63- 65.

[72] Ibid. pp. 65.

[73] Wellman, Judith. Women in the Abolitionist Movement in Seneca County. 2006. pp. 10.

[74] Wellman, Judith. Seneca Falls Woman’s Rights Convention Historic Resources Study: Woman’s Rights National Historical Park, 2004, p. 217.

[75] Thomas M'Clintock was one of the founders of this organization. Faulkner, pp. 55.

[76] Weber, pp. 71-72.

[77] Wellman, pp. 7.

[78] Ibid.

[79] Wellman, Judith. The Underground Railroad, Abolition, and African American Life in Seneca County. 2006, pp. 220.

[80] Stanton, Elizabeth Cady. Eighty Years and More: Reminiscences 1815-1897. New York, 1898, p. 63.

[81] Historic Resources Study, pp. 234-239.

[82] Powalski, Caitlin. “Radical Transmissions: Isaac and Amy Post, Spiritualism, and Progressive Reform in Nineteenth-Century Rochester.” Rochester History, vol. 71, no. 2., pp. 1; Sandwick Schmitt, Victoria. “Rochester’s Frederick Douglass: Part One.” Rochester History, vol. 67, no. 3, pp. 13.

[83] Powalski, pp. 1.

[84] Patenaude, Monique. Bound by Pride and Prejudice: Black Life in Frederick Douglass’s New York. 2012. University of Rochester, PhD dissertation, pp. 33.

[85] Sandwick Schmitt, pp. 13.

[86] Broyld, dann j. “Rochester, a Transnational Community for Blacks Prior to the Civil War.” Rochester History, vol. 72, no. 2, pp. 2-3.

[87] Ibid. pp. 3.

[88] Snodgrass, Mary Ellen. The Underground Railroad: An Encyclopedia of People, Places, and Operations. M. E. Sharpe, 2008, pp. 167.

[89] Snodgrass, pp. 61-62.

[90] Sandwick Schmitt, pp. 12.

[91] Wellman, Judith. Uncovering the Freedom Trail in Auburn and Cayuga County, New York. 2005, pp. 21.

[92] Uncovering the Freedom Trail, pp. 26.

[93] Ibid. pp. 40.

[94] Ibid. pp. 26.

[95] Ibid. pp. 27.

[96] Ibid. pp. 54.

[97] Uncovering the Freedom Trail, pp. 121.

[98] See letter from Frances Seward to William Henry Seward, July 1, 1852. Seward Papers. July 1, 1852, , “A man by the name of William Johnson will apply to you for assistance to purchase the freedom of his daughter. You will see that I have given him something by his book. I told him I thought you would give him more. He is very desirous that I should employ his daughter when he gets her which I have agreed to do conditionally if you approve."

[99] Uncovering the Freedom Trail, pp. 122.

[100] Ibid. pp. 144-145.

[101] Martha Wright to Ellen Wright Garrison, December 30, 1860, Garrison Family Papers, Smith College, quoted in Uncovering the Freedom Trail, pp. 136.

[102] Uncovering the Freedom Trail, pp. 133.

[103] Wellman, Judith. The Underground Railroad, Abolitionism, and African American Life in Seneca County, New York, 1820-1880. 2006, pp. 1.

[104] Ibid. pp. 1.

[105] Ibid. pp. 16.

[106] Ibid. pp. 17.

[107] Ibid. pp. 17-21.

[108] Ibid. pp. 1.

[109] Ibid. pp. 21.

[110] Wellman, Judith. “The Mystery of the Seneca Falls’ Women’s Rights Convention: Who Came and Why?” 1985, pp. 71.

[111] The Underground Railroad, pp. 26.

[112] "The Mystery of the Seneca Falls" pp. 71.

[113] The Underground Railroad, pp. 25.

[114] "The Mystery of the Seneca Falls" pp. 72.

[115] Weber, pp. 23-29.

Tags

- belmont-paul women's equality national monument

- frederick douglass national historic site

- reconstruction era national historical park

- women's rights national historical park

- abolition

- women's history

- african american history

- political history

- civil rights

- anti-slavery

- religious history

- pennsylvania

- new york

- suffrage

- international relations

- underground railroad

- transportation history

- journalism

Last updated: November 19, 2020