Last updated: January 27, 2026

Article

Charlestown Navy Yard - A Brief History

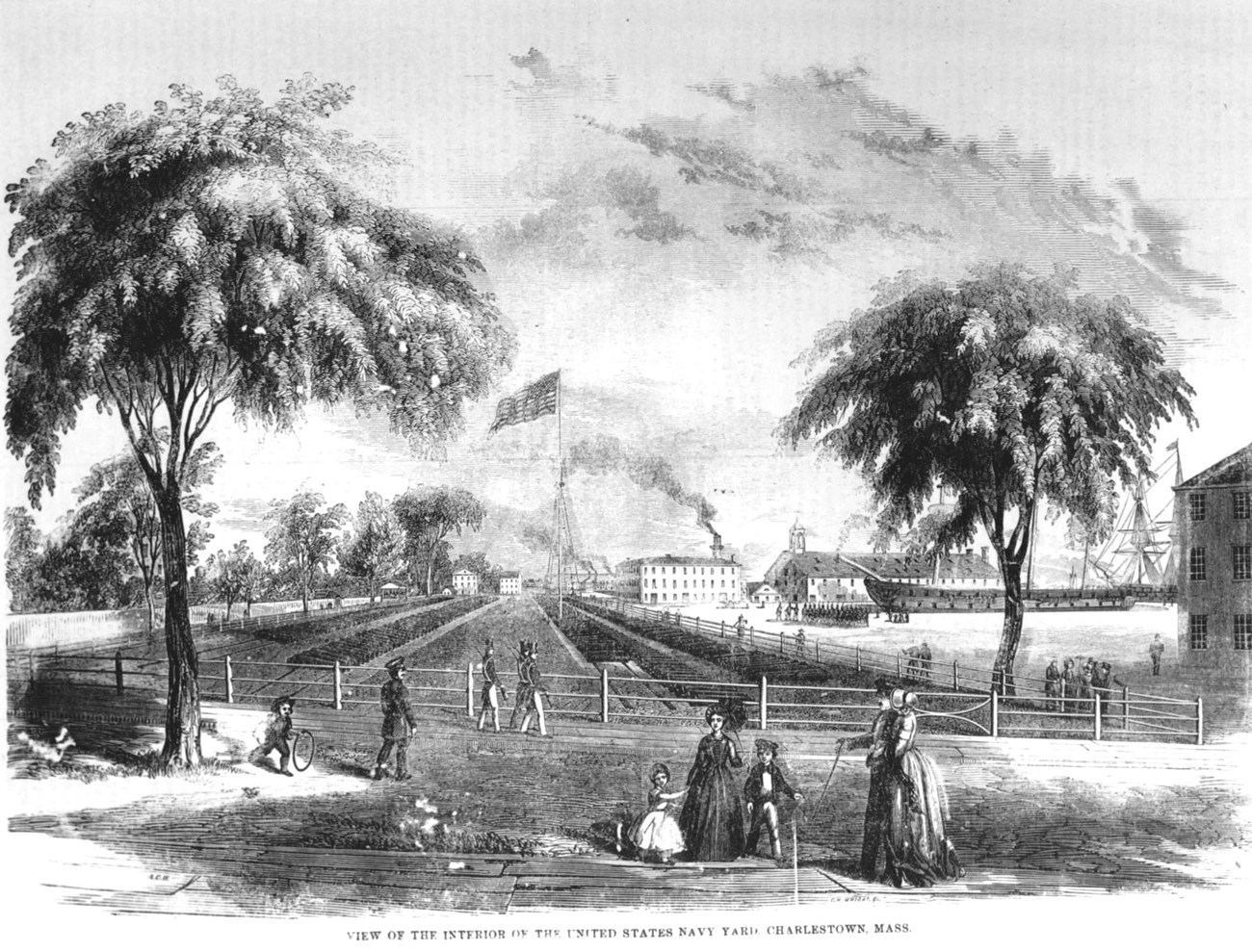

Boston National Historical Park (BNHP), BOSTS 8635.

Known also as the Boston Naval Shipyard and the Boston Navy Yard, the Charlestown Navy Yard opened in 1800 as one of the first navy yards of the US Navy. The Charlestown Navy Yard lies in Boston's Inner Harbor and is at the junction of the Charles and Mystic Rivers. By the time the Yard closed in 1974, it had spread across many acres and contained numerous buildings, piers, dry docks, and more.

Long before the United States established the Charlestown Navy Yard, the tidal flats of this area provided seasonal sustenance to local Indigenous communities for thousands of years. These communities, whose descendants are the Massachusett, called the land Mishawum or "Great Springs." These flats also became a landing for British infantry transports in the Battle of Bunker Hill on June 17, 1775.

The newly-formed United States emerged from its War of Independence facing threats to its overseas trade. As recommended by President George Washington in 1794, Congress passed the Navy Act, approving the construction of six frigates. This act reestablished the United States Navy that originated as the Continental Navy during the American Revolution. One of those six frigates from 1794 was USS Constitution.

BNHP, BOSTS 8789.

Getting Started

The US Navy established the Charlestown Navy Yard along with five other navy yards. The other yards were located along the Atlantic coast of the 16-state union: Portsmouth, New Hampshire; New York City, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Washington D.C.; and Norfolk, Virginia.

Among the first buildings constructed in the Yard was a storehouse, called the Navy Store, now known as Building 5; and military housing: the Commandant's House, the Officers' Quarters, and the Marine Barracks. The first ship built in the Navy Yard was the USS Independence in 1814. As the biggest ship, called a ship-of-the-line, in the early US Navy, it served alongside smaller frigates like the USS Constitution.

Workers in the yard built and repaired ships that challenged the British Navy in the War of 1812. Among those ships repaired in the yard were five of the original six frigates ordered in 1794. All were at least 13 years old by the start of the War of 1812 and all needed repairs. None of these frigates had been built in the Navy Yard. The War of 1812 and the Mexican American War (1846) presented the first big challenges for the workers in the Charlestown Navy Yard since it opened in 1800.

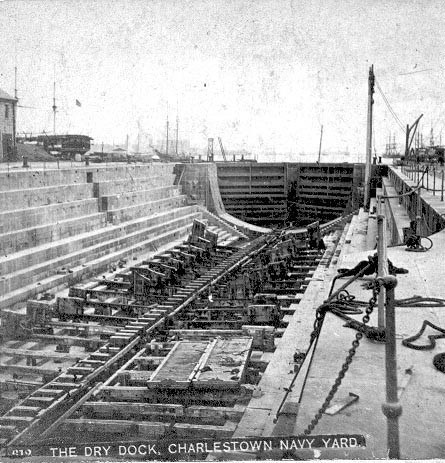

By the 1850s, many ships in the US Navy had steam-powered engines for propulsion, with masts and sails kept as a secondary source of power. The Navy added two new features to the Charlestown Navy Yard by the 1850s: the Ropewalk and Dry Dock 1, both steam-powered. Two of the most famous of the wooden, steam ships built in the yard were the USS Hartford, which became the flagship of Admiral David G. Farragut during the Civil War, and the USS Merrimack, which became the Confederacy's Virginia.

BNHP, BOSTS 8875-2

The Civil War

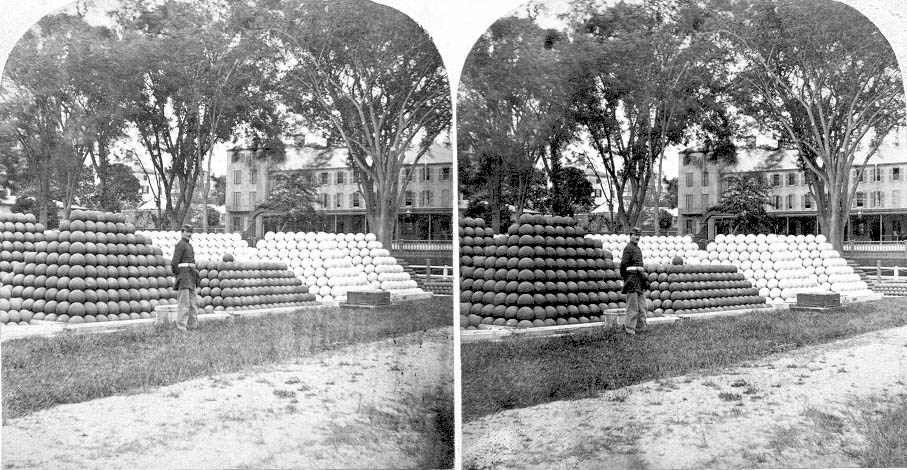

The biggest challenge that faced the US Navy in the 19th century was the American Civil War. During the Civil War, the US Navy had to patrol and blockade over 3,000 miles of the southern coast of the United States, some of its interior rivers and international waters. The Navy had fewer than 90 ships in 1861 and it now needed hundreds more. During the war, the Charlestown Navy Yard became one of the Navy’s most productive yards.

Workers at the Charlestown Navy Yard built, repaired, or remodeled over 170 warships during the war. Some of these ships included private ships workers converted to warships to augment the US naval fleet. One of the newer buildings operating in the Navy Yard during the Civil War was the Machine Shop. Machine Shop workers specialized in steam engines for wooden ships and for the newer ironclad ships.

The most well-known naval battle of the Civil War was the clash of the ironclad ships at Hampton Roads, Virginia. This battle inspired the building of numerous ironclad ships by the US Navy. Workers at the Navy Yard and at nearby contractors’ yards launched about ten ironclads during the war.

The American Civil War also led to the innovative ship design known as the double-ender, a ship intended for river travel. This ship could change direction without turning around; workers in the Charlestown Navy Yard made five of them.

In 1865, workers installed a railway system in the yard to move supplies into and around the yard. Following the Civil War, the workload and the number of workers decreased at the Charlestown Navy Yard, continuing a Navy tradition of post-war lulls in shipbuilding.

BNHP, BOSTS 8650-2

BNHP, BOSTS 15878

The New Navy

A modernization period began in the US Navy in the 1880s, called the era of the New Navy. The US Congress authorized the building of a fleet of steel warships. Part of this authorization included building a second, larger dry dock (Dry Dock 2), additional piers, and a new Forge Shop for the Charlestown Navy Yard. The Navy expected the yard to build and repair larger steel ships and manufacture all the anchors and anchor chains for this New Navy.

By the Spanish-American War in 1898, Navy ships had hulls of iron or steel and Charlestown Navy Yard workers repaired over fifty of these ships during this short war. In 1904, sixty-five thousand spectators witnessed the launching of the first all-steel ship built at the Charlestown Navy Yard, the USS Cumberland.

By 1915, the Navy had expanded the yard by constructing nearly 50 new buildings and further developing the yard's railroad system. The US Navy was becoming one of the world's largest navies.

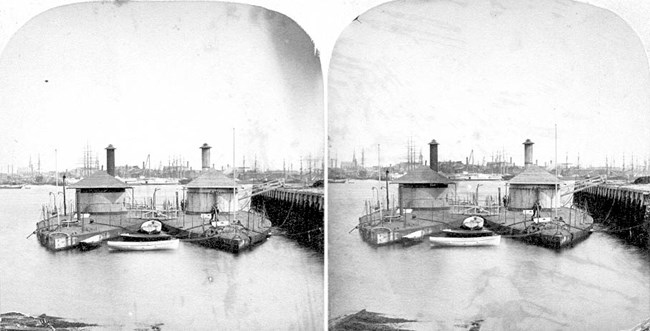

BNHP, BOSTS 10263-1

World War I

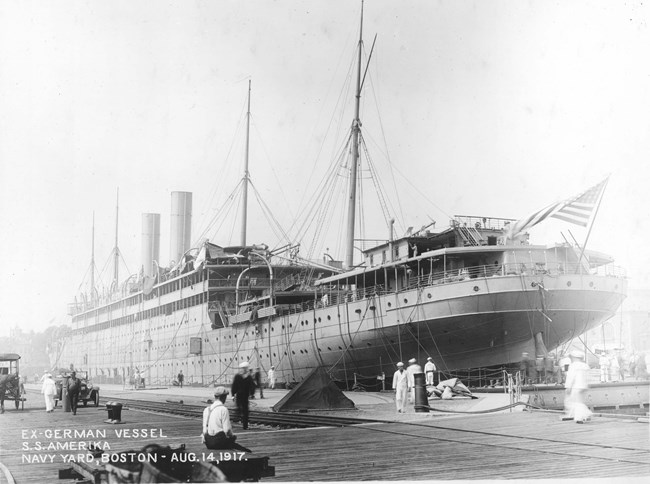

When the U.S. formally entered World War I (WWI) in 1917, the US Navy had the large task of transporting thousands of US Army soldiers to France and back. Charlestown Navy Yard workers converted three captured German ocean liners and other ships into troop transports; one of the converted liners, USS America, made nine round trips.

Yard workers repaired and outfitted over 450 ships during WWI including battleships and submarines. Because many Yard workers enlisted in the armed forces in WWI, the Navy turned to women to fill jobs at the Charlestown Navy Yard. The Navy created an enlistment rank called Yeomen (F), F for female, in the Naval Reserve. Over 700 Yeomen (F) worked as telephone and telegraph operators, stenographers, bookkeepers, and typists in the yard.

In 1917, ten thousand spectators came to the Charlestown Navy Yard to witness the launching of the largest ship ever built in the yard up until that time, USS Bridge. The Bridge was the first refrigerated supply ship built by the US Navy. A post-war decrease in US naval forces plus an international treaty that limited navy sizes decreased the work force at the Charlestown Navy Yard in the 1920s.

BNHP, BOSTS 10536-136

BNHP, BOSTS-7412

World War II

Starting in the 1930s, workers in the Charlestown Navy Yard started the biggest ship-building and ship-repair era in the history of the Charlestown Navy Yard. By the time World War II (WWII) ended in 1945, workers in the yard had built approximately 300 craft and served another 4,600 ships. Destroyers that took one year to complete in 1941 were finished in only 3-4 months by 1945. Due to increased production during WWII, the Charlestown Navy Yard did not have enough space to complete the workload. In response, the Navy built additional facilities at the South Boston Annex along Boston's Outer Harbor.

Over half the ships ever built in the yard were built by its workforce during WWII when the yard had over 50,000 employees. During this time of crisis, the Navy Yard opened its doors to women and people of color. For the first time, the opportunity to make livable wages was available to thousands of people.

BNHP, BOSTS 7719-5086.

The Cold War

After World War II, workers in the Charlestown Navy Yard upgraded Navy vessels including the Fletcher-class destroyer, USS Cassin Young. These vessels received advanced RADAR and SONAR systems, and some received new engines, missiles, and other enhancements during the 1950s and 1960s in the yard. The Charlestown Navy Yard specialized in the building and repair of destroyers during WWII and the Cold War. Although not built in the yard, USS Cassin Young symbolizes that effort. USS Cassin Young has been a part of the National Parks of Boston since 1980.

Navy Yard workers were mostly civilians supervised by naval officers, and the yard functioned like any other industrial plant. While these workers provided critical labor and many excelled in their positions, some experienced racism, sexual harassment, and discrimination. The naval officers had to resolve these issues and others that involved wages, working hours, conditions, and apprenticeship programs. Safety was always a concern since some jobs in the shipyard were hazardous; injuries and deaths from accidents were not unknown over the Yard's long history.

More than a Shipyard

Within the Charlestown Navy Yard, the Navy provided housing to its military personnel, including the Marines, who worked in the yard. The Charlestown Navy Yard also had a succession of receiving ships docked at the yard for over a hundred years. A receiving ship was a barracks for new sailors and for sailors moving from one ship to another. Sailors also had on-the-job training aboard receiving ships. Starting in 1933, sailor housing and training was brought ashore, ending the era of the receiving ships.

Starting in 1915, the yard served as the headquarters of the First Naval District. Naval officers in the yard had the responsibility of defending parts of the Atlantic Coast of the United States. There was also a small military prison in the Navy Yard.

During all its years of service, the Charlestown Navy Yard not only provided ships with food, clothing, fuel, weapons, and other items, but also sent supplies to overseas naval stations. The Charlestown Navy Yard supported humanitarian and non-military missions. For example, in 1847, USS Jamestown departed the Navy Yard to deliver food to the people of Ireland during the Great Famine and Admiral Richard Byrd's Antarctica scientific expedition sailed from the yard in 1933.

BNHP, BOSTS 8627

The End

The Charlestown Navy Yard operated for nearly 175 years from the age of sail to the age of steel. The US Navy promoted and protected American interests across the globe, and Charlestown Navy Yard workers provided the Navy with ships and supplies. The yard also served as the center of production for rope, anchors, and anchor chains for the entire Navy.

The federal government closed the Yard in 1974 and the Navy planned to rely more on private shipyards for its needs. The federal government set aside 30 acres of the yard to serve as a national historic site; the remaining 100 acres and over 100 buildings became privately owned.

By preserving a portion of the Charlestown Navy Yard, the National Park Service memorializes the contributions of thousands of civilian workers and military personnel. The exhibit, "Serving the Naval Fleet" in the Charlestown Navy Yard Visitor Center in Building 5 tells some of this story. USS Constitution and the USS Constitution Museum, affiliated with the ship since 1972, are also part of the historic Charlestown Navy Yard. The Charlestown Navy Yard became a National Historic Landmark in 1966.

Sources

- Akers, Regina T. "African Americans in General Service, 1942." Naval History and Heritage Command. March 23, 2017. https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-ii/1942/manning-the-us-navy/african-americans-in-general-service--1942.html.

- Bearss, Edwin C.. Historic Resource Study: Charlestown Navy Yard, 1800-1842, Volume I and Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, October, 1984.

- Bearss, Edwin C. and Frederick R. Black. The Charlestown Navy Yard 1842-1890. Boston, Massachusetts: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, July 1993.

- Black, Frederick R.. Charlestown Navy Yard: 1890-1973, Volume I and Volume II. Boston, Massachusetts: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1988.

- "Byrd Ship Sails for Antarctica: Harbor Craft Bid Adieu to Departing ..." Daily Boston Globe, October 12, 1933, 18.

- Carlson, Stephen P.. Charlestown Navy Yard Historic Resource Study, Vol 1-3. Boston, MA: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2010.

- "For the New Ship, 65,000 People Cheer." Boston Daily Globe. August 18, 1904, 8.

- Hepburn, Richard D., P.E. History of American Naval Dry Docks: A Key Ingredient to a Maritime Power. Arlington, VA: Noesis, Inc., 2003.

- "Launch New Supply Ship." Boston Daily Globe. May 18, 1916, 11.

- National Park Service, Division of Publications, U.S. Department of the Interior, Charlestown Navy Yard, 1995.

- "On March 28, 1847, USS Jamestown Leaves Charlestown Navy Yard on Humanitarian Mission to Help Ireland." Irish Boston History & Heritage. March 28, 2020. https://irishboston.blogspot.com/2020/03/on-march-28-1847-uss-jamestown-leaves.html.

- Stevens, Christopher, Margie Coffin Brown, Ryan Reedy, and Patrick Eleey. Cultural Landscape Report for Charlestown Navy Yard. Olmstead Center for Landscape Preservation, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, 2005.

- "Transformed Land in Charlestown." Signs By Friends of the Boston Harborwalk. Accessed August, 2021. https://boshw.us/sign/transformed-land/?lang=english.

- "World War I." Naval History and Heritage Command. Accessed March 2022. https://www.history.navy.mil/browse-by-topic/wars-conflicts-and-operations/world-war-i.html.