Last updated: January 20, 2024

Article

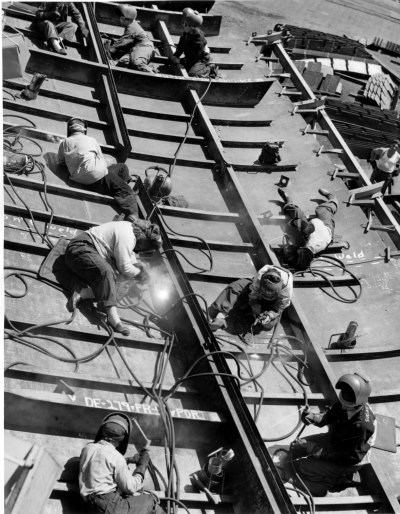

"We Can Do It!" - Shipbuilding Women invade the Charlestown Navy Yard

BOSTS 7412

The enemy has struck a savage treacherous blow. We are at war, all of us! There is no time now for disputes or delay of any kind. We must have ships and more ships, guns and more guns, men and more men – faster and faster, there is no time to lose. The Navy must lead the way. Speed up – It is your Navy and your nation!

BOSTS 14958

Frank Knox, Secretary of the US Navy, sent this desperate message to all the shipbuilding facilities of the US Navy on December 10, 1941, just three days after the surprise Japanese attack on the U.S. fleet at Pearl Harbor thrust the United States into the Second World War.

The 17,000 civilian employees on the Boston Navy Yard's 1941 rolls were not numerous enough for the facility to increase building, converting, and repairing ships to levels demanded by wartime needs. In addition, thousands of these men were expected to leave civilian life and join the Armed Forces. To get the work done, Boston Navy Yard turned to people who would not have had a chance at being hired in peacetime: women; African-American men; retirees; men without specialized training; disabled men. These people stepped up to the task: by mid-1943, over 50,000 civilians came to work each day at the shops, offices, piers, and dry docks of the Boston Navy Yard and its annexes in Chelsea, South Boston, and East Boston.

Between 15 and 20% of these workers were women. Numbering over 8,000 in 1943, these women were thrown into roles that the shipbuilding world had not previously opened to them. Though some of them worked in clerical positions that had been deemed acceptable for women since World War I, the great majority became welders and electricians, machine operators and pipefitters, mechanics and painters. Kept separate from Navy personnel berthed on ships in repair or overhaul, women took their tools to the hulls of new ships under construction or spent their workdays in one of the many specialized shops that produced ship components.

The Shipyard News, Boston Navy Yard's newspaper, featured women of all backgrounds in its wartime pages: college-educated women; girls fresh from high school; married women; grandmothers; women with husbands or brothers fighting overseas. As their faces smile up at us from the newsprint, we should not overlook the great challenges the women themselves recounted when interviewed about their Navy Yard experience. They worked in extreme conditions with dangerous tools and materials, sometimes alongside male employees who did not believe that they were up to the job. When they returned home after their 8- or 9-hour shift, they were expected to shop, cook and clean, care for children, and attend to other duties of women in the home. They were a proud group, taking home excellent wages and determined to contribute to the home front war effort.

By 1945, the wartime shipbuilding effort had provided the US Navy with the fleet it needed for victory in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. Women had played a significant role in Boston Navy Yard's leading place in that effort. Now, however, their time as shipbuilders was over. As production was reduced at Boston, more and more women were released from the workforce. Though they were gone from the pier and the shops, they carried their experiences with them into the peacetime world. Within two decades, these women and their daughters would create a new women's movement that would fight for American women's right to join the workforce in any capacity they desired.

Contributed by: Polly Kienle

Sources & Further Reading:

- Frederick Black, Charlestown Navy Yard 1890-1973, Volume II, Cultural Resources Management Study No. 20. (Boston: Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1988).

- Boston National Historical Park. Boston Naval Shipyard Oral History Project.

- Stephen P. Carlson. Charlestown Navy Yard: Historic Resource Study, Vols. I-III (Boston: Division of Cultural Resources, Boston National Historical Park, National Park Service, 2010).

- Maureen Honey. Creating Rosie the Riveter: class, gender, and propaganda during World War II (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1985).

- George O. Mansfield. Historical Review: Boston Naval Shipyard – formerly – Boston Navy Yard 1938-1957 (Boston: Boston Naval Shipyard Administrative Department, 1957).