The Last Grand Adventure

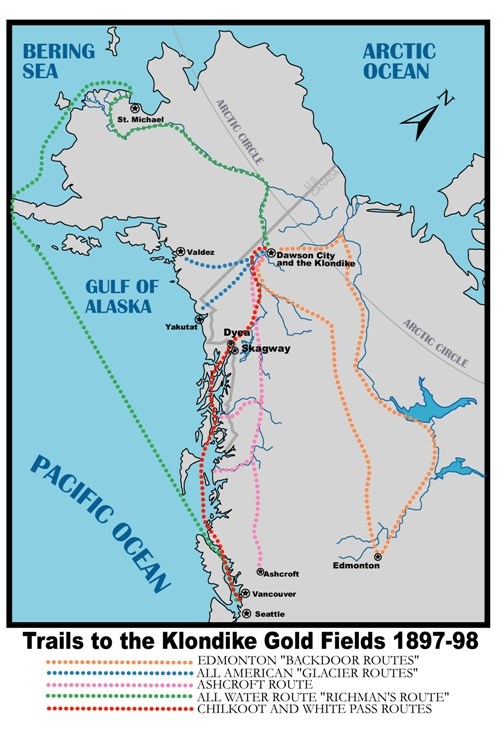

NPS Cries of "Gold! Gold! Gold in the Klondike!" started a race. 100,000 hopeful miners sprinted toward Alaska and the Yukon with their eyes on riches. Alaska Native and First Nations communities adapted to hold onto another kind of wealth: their culture, land, and way of life. Through the fall and winter of 1897-98, ships delivered gold seekers to Skagway and nearby Dyea, Alaska. Both mushroomed from tents to towns in a matter of months. Merchants built a two-mile dock on beaches where Tlingit people traditionally fished. Criminal boss Jefferson “Soapy” Smith preyed on naive gold seekers. Prostitutes made more money than laundresses, cooks, dressmakers, or nurses. Skagway, at the head of the White Pass Trail, was founded by a former steamboat captain named William Moore. His small homestead was inundated with some 10,000 transient residents struggling to get their required year's worth of gear and supplies over the Coast Range and down the Yukon River headwaters at lakes Lindeman and Bennett. Dyea, three miles away at the head of Taiya Inlet, experienced the same frantic boomtown activity as goldseekers poured ashore and picked their way up the Chilkoot Trail into Canada.

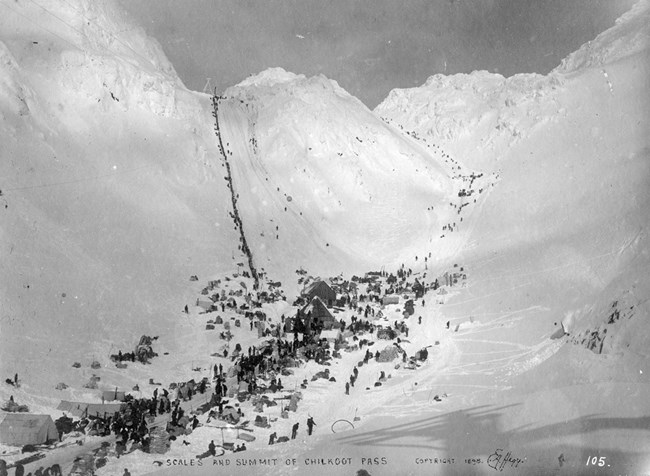

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, KLGO Library SS-32-10566 Stampeders faced their greatest hardships on the Chilkoot Trail out of Dyea and the White Pass Trail out of Skagway. There were murders and suicides, disease and malnutrition, and deaths from hypothermia, avalanche, and possibly even heartbreak. The Chilkoot Trail was the toughest on men because pack animals could not be used easily on the steep slopes leading to the pass. Until tramways were built late in 1897 and early 1898, the stampeders had to carry everything on their backs. The White Pass Trail was the animal-killer, as anxious prospectors overloaded and beat their pack animals and forced them over the rocky terrain until they dropped. More than 3,000 animals died on this trail; many of their bones still lie at the bottom on Dead Horse Gulch. During the first year of the rush an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 goldseekers spent an average of three months packing their outfits up the trails and over the passes to the lakes. The distance from tidewater to the lakes was only about 35 miles, but each individual trudged hundreds of miles back and forth along the trails, moving gear from cache to cache. Once the prospectors had hauled their full array of gear to the lakes, they built or bought boats to float the remaining 560 or so miles downriver to Dawson City and the Klondike mining district where an almost limitless supply of gold nuggets was said to lie. By midsummer of 1898 there were 18,000 people at Dawson, with more than 5,000 working the diggings. By August many of the stampeders had started for home, most of them broke. The next year saw a still larger exodus of miners when gold was discovered at Nome, Alaska. The great Klondike Gold Rush ended as suddenly as it had begun. Towns such as Dawson City and Skagway began to decline. Others, including Dyea, disappeared altogether, leaving only memories of what many consider to be the last grand adventure of the 19th century. Learn More!

Many Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park publications are currently available free online through the National Park Service's Park History site.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library SS-126-8831 |

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.