Photo courtesy of the Alaskan State Library William Norton Collection (ASL- P226-867)

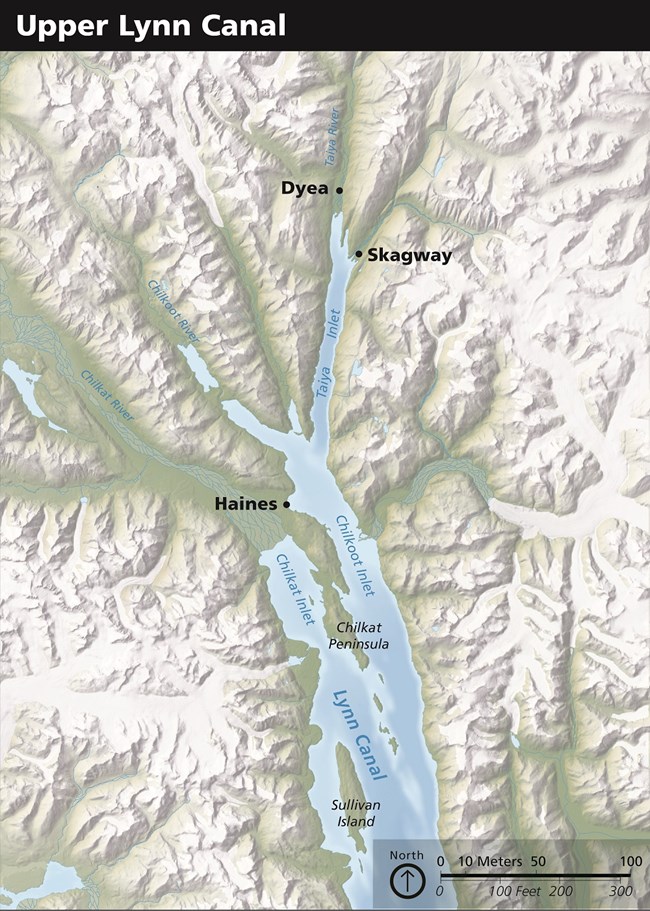

NPS image A Need for Law and OrderDuring the Klondike Gold Rush, boomtowns popped up on the edges of "the Last Frontier." In Southeast Alaska, Skagway and Dyea became important ports on the route to the gold fields. These were lawless communities swarming with gold hungry stampeders. Sam Steele of the North-West Mounted Police described early Skagway as "little better than a hell on earth" and "about the roughest place in the world."Several things added to the disorder in Skagway. First, poor conditions closed the White Pass Trail, that started in Skagway, repeatedly stranding stampeders in town. Second, the border between the United States and Canada (then part of Great Britain) was still in dispute. Each country wanted the ocean access of the port towns. As a result, the United States Army gave orders to send troops to Alaska. There they could bring law and order, show the American flag, and protect people and property. Initially four companies of the 14th Infantry, as well as a Hospital Corps were sent to Alaska. By 1899, only one company remained. In May 1899 the 14th Infantry was relieved by another regiment, fresh off of fighting in the Spanish-American War, the Buffalo Soldiers of the 24th Infantry.

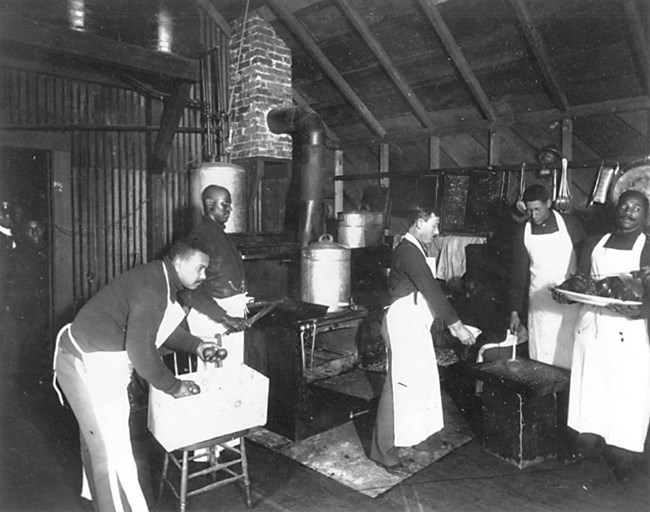

Photo courtesy of the Alaska State Library William Norton Collection (ASL-P226-868) Buffalo Soldiers of Company LThe 24th Infantry was one of four segregated regiments of African American soldiers in 1899. The men in these units were frequently called “Buffalo Soldiers” based on their history fighting in the Indian Wars. This term was eventually used for all black soldiers, even if they had not fought in the Indian Wars. The 24th Infantry Regiment began in 1869, but Company L formed in March 1899. Some of the men in Company L were likely born as slaves, several had fought in the Indian Wars, many had fought in the Spanish American War. Company L started at Fort Douglas, Utah, but quickly proceeded to the Presidio in California. In early May 1899 they received orders to go to Alaska. After passing through the Vancouver Barracks, Company L, boarded the S.S. Humboldt in Seattle and sailed north. Isaac C. Jenks, a 1st Lieutenant, and 46 soldiers disembarked to serve a year at Fort Wrangell before rejoining the rest of the group. The majority of the unit arrived to Dyea, Alaska May 20, 1899. The same day they arrived, Company B, 14th Infantry departed. With that, a unit of black soldiers replaced a unit of white soldiers.

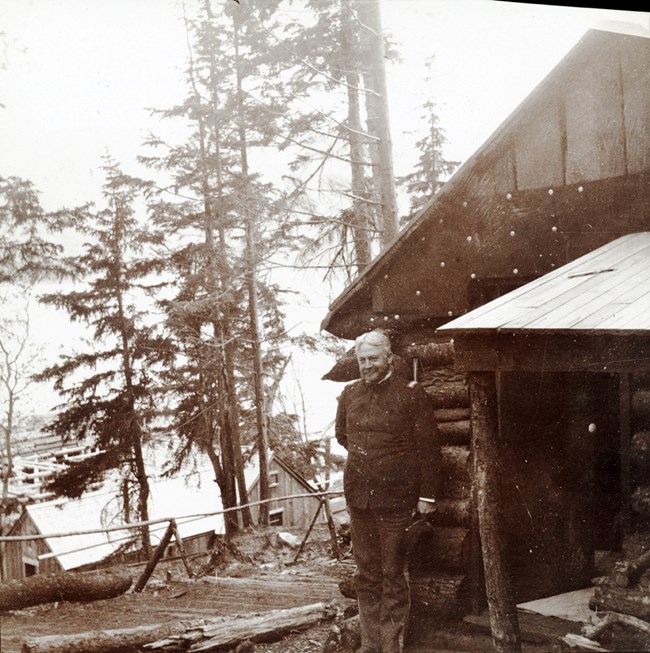

Photo courtesy of the Alaska State Library F.B. Bourn Photo Collection (ASL P99-164) Camp Dyea is DestroyedJuly 1899 must have been unusually dry. Mid-month a forest fire broke out south of the military camp. However, the wind came from the north and extinguished, rather than spread the flames. Fires flared up along the western side of Lynn Canal between Dyea and the Haines Mission. Fires in the Skagway River Valley delayed the White Pass & Yukon Route trains. On July 28th, fire called on Dyea again and this time the camp was not so lucky. A military document for July 1899 describes what happened: “At about 8 AM that day a fire was discovered about 1000 yds north of Camp. Upon examination it was found that efforts to extinguish it would be unavailing, and the preparations for removal were ordered. After removing as many stores as possible the command left at 610 PM – a guard of five men remaining. In about twenty minutes the wind changed, and the fire came down rapidly through the forest, destroying everything, in its path, including all buildings occupied by troops.” The camp had been surrounded by fire on three sides. The five man guard fled for their lives as the dock, barracks, officers cabins, and storehouses went up in flames. All of the camp records were also lost. Captain Hovey hastily moved his troops to Skagway and resurrected Camp Skagway which had been abandoned by Companies A and G, 14th Infantry.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugaman Collection, KLGO Library MD-16-8846 Life At Camp SkagwayIn Skagway the troops faced new challenges. The first obstacle was finding everyone in the unit a home. Initially the troops camped on Captain Moore’s property. Longer term accommodations for the troops were found at the Hotel Astoria, located on 6th Avenue, east of Broadway. Eventually, a two story barracks was constructed on 6th Avenue at the present day location of Mollie Walsh Park. Today, this former barracks building can be seen on Broadway as the Lynch & Kennedy building. Captain Hovey also rented a number of smaller buildings scattered through town for himself, his officers, and some of his enlisted men whose families were with them.Military Duties Company L helped keep law and order in Skagway. They responded to mysterious gun shots in the downtown area and escorted angry deserters back to their ship. They officially notified the town of the assassination of President McKinley and mourned him with gun salutes and mourning sashes. One winter they provided overnight fire patrols to ensure the town was safe. In October 1901 they were instrumental in preventing major damage during the Skagway River flood. Detachments provided military escort service for Canadian officials traveling from the disputed border to the Skagway port. The troops also provided ongoing support for incidents between white settlers and Tlingit people in Pyramid Harbor and Haines Mission. Another time, they helped recover the bodies of murder victims Bert and Florence Horton. Despite a lack of combat, the troops continued with training and drilling. December 1899 found them learning army signal code using signaling lanterns. In 1900 they received a Gatling gun at the barracks "in case of war or riot to maintain the dignity of Uncle Sam." (Daily Alaskan, Sept 6, 1900). They installed hot blast stoves and plumbing in their barracks buildings making daily life in Alaska more pleasant. When it was too cold to drill outside during the winter of 1902, they drilled in their barracks and attended training classes indoors. An inspection of all Alaskan posts by Major H.E. Tutherly in October 1901 found the Skagway troops "had reached a high degree of efficiency" and passed inspection (Daily Alaskan, October 29, 1901).

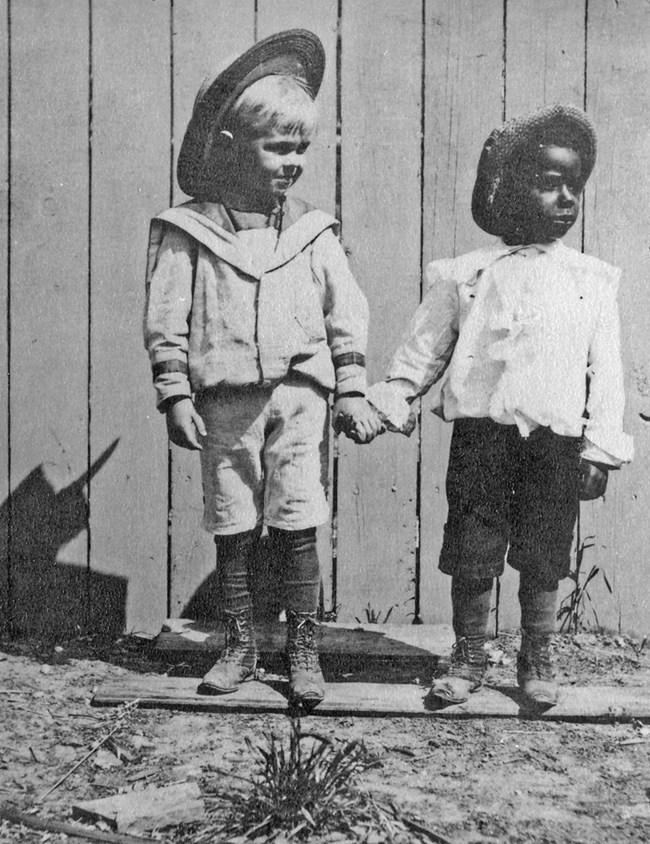

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, KLGO 32333 The men of Company L worked to integrate themselves in to the town. A number of the soldiers were active in the local Baptist Church. A "colored" Sunday school formed and had "good and zelous attendance from the start." (Daily Alaskan, January 1, 1902). There appears to have been both a singing quartet and instrumental quartet often performing at Baptist Church events. Private James E.B. Reed gave an evening lecture at the local Y.M.C.A. Many men participated in Skagway's active saloon culture. Perhaps one of the best ways Company L joined town activites was through baseball. In May 1900 the soldiers made up one of the first three baseball teams in Skagway. These three teams played during the season against each other and teams from Bennett and Juneau. A rivalry developed in the newspaper between the soldier team and the "Skagway team" made up of railroad employees and firemen. The soldiers were also active with football games among themselves, attending the rifle club, and participating in Skagways Fourth of July tug-of-war competition (still a tradition in modern Skagway's Fourth of July). However, in a time with Jim Crow laws spreading throughout the United States, Alaska was not immune to racism. In 1900, controversy arose when 30 men of Company L joined the local Y.M.C.A. Many in town objected to having a desegregated club. At the same time that Company L was protecting town citizens, Vaudeville-style shows embracing racist stereotypes were promoted in town as entertainment. When Private Robert Grant was refused entry to a white woman's "bawdy house" he threw a rock through the window and was arrested for property damage. He was sentenced to three months in jail and dishonorably discharged from the military. Several soldiers brawled at saloons, both with each other and non-soldiers. Without first hand accounts, it is hard to say what it was really like for these men to serve in Skagway.

Photo courtesy of the Alaska State Library Paul Sincic Collection (ASL-P75-144) Company L Leaves SkagwayIn early 1902 at least 50 of the soldiers of Company L finished their three year enlistment terms. Some chose to reenlist, but many chose to end their military service. Company L celebrated this mass departure with a ball. "The ladies were radiant in party dresses, and they were gallantly swung to the best dance music that Skagway could afford. The hall was an unremitting scene of jollity and merriment. The affair was swell." - Daily Alaskan, February 5, 1902 In May 1902, Camp Skagway received news that Company L would move to Fort Missoula in Montana. The 106th Battery of the Coast Artillery would replace them in Skagway. In the week before their departure there were many articles in the paper lamenting the loss of Captain Hovey and celebrating him. The Pullen House hosted a lavish banquet in his honor, he was given lifetime membership to the Elks club, and speeches dedicated to him were published in the paper. Other articles mention the departure of the white officers and their wives, tauted as "society favorites." There is not much mention of the numerous black soldiers who were the majority of the company. Based on the newspaper account, their departure was most noticably felt with the loss of the baseball team. Leaving on short notice meant that the rivalry for the Kirmse championship cup ended with a tie between the soldiers and the "Skagway team." Almost three years to the day they arrived, Company L boarded the SS City of Seattle and sailed south.

Photo courtesy of the Alaska State Library Buffalo Soldiers and the National ParksNational Parks were just getting their beginnings towards the end of the 19th century. The National Park Service did not exist at the time early National Parks like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia were created and would not for another 25 years. From 1891 to 1914, Yosemite, Sequoia & General Grant (now Kings Canyon) National Parks were under the protection of the United States Army. The army was the perfect organization for this sort of duty. Campaigns in the American West had imbued Army soldiers with the skills necessary for patrolling the vast wilderness that the new National Parks offered the public. John Muir, who held a special place for National Parks in his heart, wrote about the military presence in Yosemite. "This year, I am happy to say, nearly every trace of the sad sheep years of repression and destruction have vanished. Blessings on Uncle Sam's blue-coats! The quiet, orderly soldiers have done this fine job, without any apparent friction or weak noise, in the still, calm way that the United States troops do their duty."-John Muir Buffalo Soldiers constructed the first museum in a national park. A 70-acre facility, the museum was an arboretum with a nature trail constructed through it. It also included signs giving the names of all plants present, including their species name in Latin. Companies of these same soldiers also escorted President Theodore Roosevelt on a trip to Yosemite in 1903. Roosevelt met up with John Muir and they spent three days camping alone in the Yosemite high country. Because of the impression Muir made upon Roosevelt, Yosemite National Park would be expanded and control of the park would be turned back over to the federal government. Roosevelt would later go on to sign into law the Antiquities Act, which gives the President the power to proclaim an area of natural or historical value as public lands. "A journey through this park and the Sierra Forest Reserve to the Mount Whitney country will convince even the least thoughtful man of the needfulness of preserving these mountains just as they are…" -Captain Charles Young These African American soldiers played a vital role in the coming of law and order to the gold rush boomtowns of Skagway and Dyea. Their efforts to promote safety and to show the American flag should not go unnoticed. These celebrated soldiers who fought on the Western frontier, found themselves sent to the Last Frontier to perform similar duties. These very same soldiers were also counted upon to help protect our Nation's early National Parks on the frontier of the conservation movement. It would be a grave injustice to let the contributions of the Buffalo Soldiers to go unnoticed. Their presence in Skagway and Dyea, which would eventually become a National Historical Park, parallels the duty they were assigned to in early National Parks like Yosemite and Sequoia. |

Last updated: July 25, 2024