National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Candy Waugamans Collection, KLGO Library, White Pass Trail WL-69-8874.

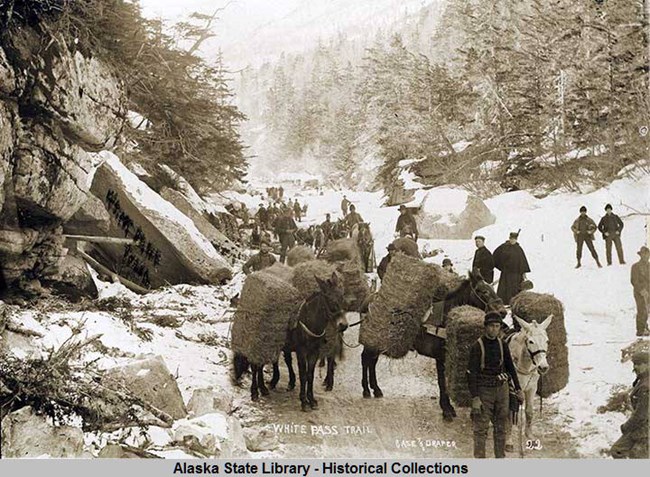

Skagway and Dyea are two important entry points into the interior of Canada because of their location at the end of the Inside Passage. When the first gold prospectors arrived at the end of the Lynn Canal in 1897 they had to make a decision. They could choose the 45 mile White Pass Trail out of Skagway or the 33 mile Chilkoot Trail out of Dyea. The two trails end at the shores of Lake Bennett in the Yukon Territory at the headwaters of the Yukon River. Both trails are ice free and low in elevation making them the most practical way to cross over the Coastal Mountains into the interior of Canada. The White Pass Trail lacked the steep slopes of the Chilkoot, but it was 10 miles longer and had its own obstacles. The trail became clogged with mud during the wet fall months of 1897, making it impassable at some spots.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55742a. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. The Moores and MooresvilleCaptain William Moore and his sons Billy and Ben were the first Euro American settlers to make Skagway Bay their home. Ten years before the Klondike Gold Rush the Moore family claimed a 160 acre homestead in the valley and called it Mooresville. Although the Tlingit people had lived in Southeast Alaska for thousands of years, they lived in Skagway only seasonally. The Moores were the first settlers that intended to make Skagway their year round home. For the next 8 summers they lived in Skagway and built a small cabin, sawmill, and wharf in anticipation of the next big gold rush. No one knew if and when a big gold strike would happen, but the Moores would be ready in Mooresville. When the gold was discovered near the Klondike in August of 1896 it took several months before news of the north got out to the rest of the world.

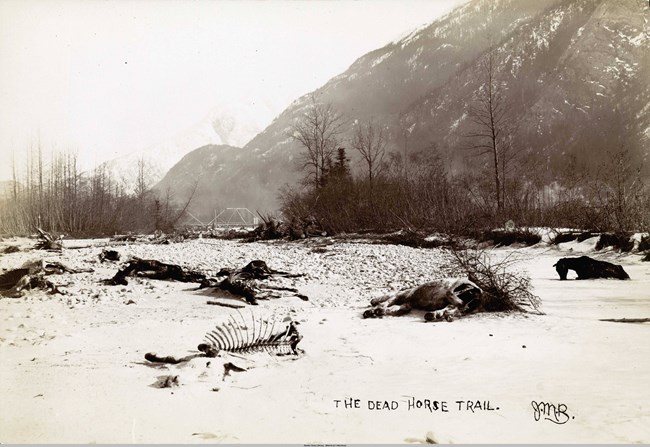

Alaska State Library, Case & Draper Photo Collection, P125-018. The Trail Turns DeadlyWhen the trail was opened by Captain William Moore it was designed for lightly loaded horses and experienced horsemen. It was not designed for the hordes of gold seekers who were bombarding the trail. Within one year of the discovery of gold in the Klondike thousands of people had attempted to cross the trail. Animals were brought up to Skagway on the same steamships that carried people and freight. Ship conditions were very harsh for everyone. Some animals were forced to stand for two weeks straight and did not get the luxury of food and water. If they did not die on their way to the Skagway they were killed in accidents, shipwrecks, or on the trails. Horses, mules, oxen, sheep, and dogs were loaded down, forced to wait in long lines, and exhausted by the trail leading over the pass. It was not uncommon for the trail to be blocked by a fallen horse.There were often long periods of waiting in lines on the trail. Stampeders refused to unload their horses that were weighed down with hundreds of goods as to not waste time reloading them.

At times the trail became impassable due to harsh weather conditions, rain, and mud. Many stampeders retreated leaving their outfits strewn along 40 miles of trail. Horses were not equipped with the constant physical demands, boggy mud holes, and slippery rocks. No one knows the exact amount of animals that took the two trails but it is estimated that 3,000 horses died in a one year period on the White Pass Trail, earning it the nickname "Dead Horse Trail." It was a brutal journey for man and beast alike.

Alaska State Library, Case & Draper Photo Collection, P39-0849. Brackett Toll RoadMany people who came to Skagway recognized the ample opportunities that the gold rush provided. A growing population created opportunities for entrepreneurs to set up businesses in Skagway. The entrepreneurs with ingenuity, capital, and little luck could make a living off of the gold rush. George Brackett was one such man. He was the former mayor of Minneapolis, Minnesota who lost his fortune during the Panic of 1893. Convinced that the White Pass was the best route to the gold fields George Brackett and his 7 sons started building a wagon road over the White Pass Trail. Brackett sank $185,000 (5.5 million in 2018) of his own money into his wagon road and charged tolls along the way to rebuild his fortune. He used 400 pounds of dynamite and black blasting powder to clear the way for the road and he charged the miners 75 cents per pound to cross. Brackett would promote the use of his wagon road at every opportunity and advertised it as “the only practical wagon road in Alaska.”

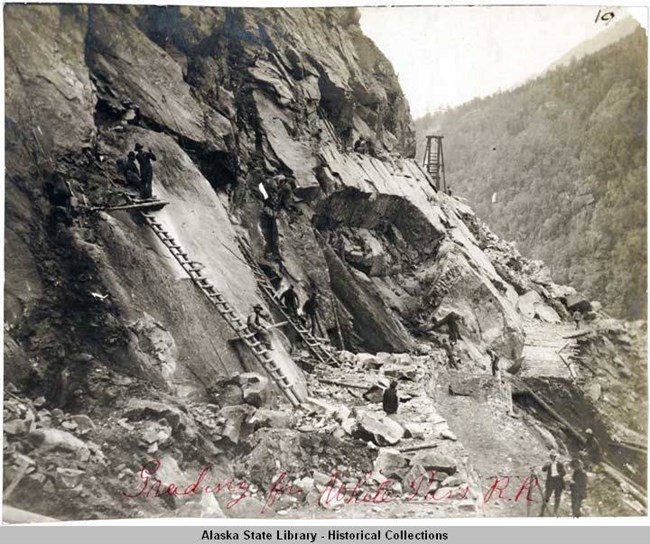

Alaska State Library, Railroads in Alaska & YT 1897-1950 Photo Collection, P275-12-076. Building a RailroadAs the fall of 1897 turned into the winter of 1898 stampeders continued to pour through Skagway and up the trail. With only a few short summer months when the lakes and rivers were not frozen it became almost impossible to bring goods to the Yukon. One man, Micheal James Heney, believed that there was a better way of getting goods over the pass rather than taking the wagon road. After witnessing $800,000 (24 million in 2018) of Klondike gold in Seattle on July 17th, 1897, Heney bought a ticket to Alaska. Heney was a Canadian railway contractor. His early fascination of railroads, building, and design didn’t shy him away from the challenge of dreaming up a railroad that went over the mountain pass. Construction would have its challenges, but was feasible. A chance encounter at the St. James Hotel in Skagway led Heney to meet Erastus C. Hawkins from Seattle and British Engineer Sir Thomas Tancrede. These two men were representing a group of British financiers, the Close Brothers, who wanted to finance the endeavor.

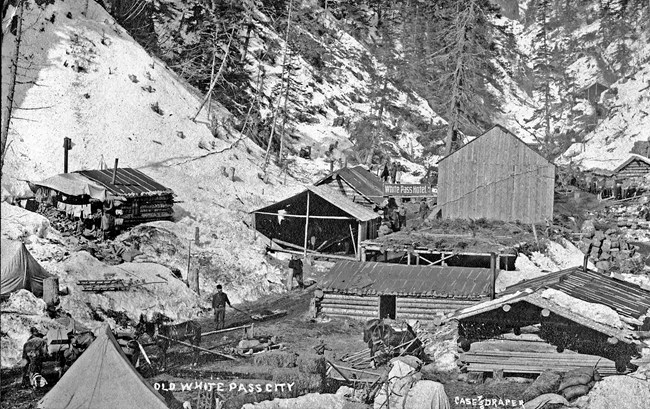

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO Library, 55740a. White Pass CityWhat today looks like a pristine valley 12 miles up the South Klondike Highway was actually the site of a tent city during the gold rush. It was the last major stopping point before the ascent to the summit of the White Pass. The valley provided one of the first flat sections of trail where a stampeder could spread out and pitch a tent before heading up the Dead Horse Gulch. The town existed for a total of two years. It consisted mostly of tents and offered 17 saloons, one for each building. One hotel in the valley called the White Pass Hotel could sleep up to 50 men at a rate of $1 per night. Many stampeders were glad to pay the fee as to not sleep outside for a night. White Pass City was also chosen as a construction crew quarters for the railway workers. When the train reached the summit in February of 1899 the city was deserted almost as quickly as it was created in 1897.

SummitRising 2,865 feet, the summit of the White Pass trail is 15 miles from the shores of Skagway. Conditions at the summit were very harsh for gold seekers passing over the border into Canada. During the summer months millions of mosquitoes use these lakes as breeding grounds. In the winter it could snow up to 200 feet on the pass with wind chills at -80 degrees F. These weather conditions made the summit uninhabitable by most people. The North West Mounted Police (NWMP) stationed at the summit of the White Pass lived in very rough conditions. Expecting trouble from stampeders they came equipped with machine guns. Their job was to collect duties and customs to be paid to the Queen of England. At the time Canada was a colony of the British Empire.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George & Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59624a. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation. After The Gold RushToday, the White Pass Trail is one of four units in the Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. Parts of the historic trail can be seen from the Klondike Highway and White Pass & Yukon Route railroad. Most of the original trail has been disturbed throughout the years from the construction of the railway, highway, and river system. |

Last updated: February 10, 2020