|

Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

Olmsted Archives Bushnell Park (Hartford, CT)In 1853 Reverend Horace Bushnell, motivated to improve access to nature for the city’s poor working class, persuaded the Hartford City Council to acquire the land to create a park. In November of that year the Council voted unanimously to spend $105,000 to buy the land that would become Bushnell Park. When Hartford voters approved the spending, it was the first time in the United States that a municipal park was to be conceived, built, and paid for by citizens through a popular vote.Frederick Law Olmsted would have been a logical choice on who to lead this project, with his local roots and a lifelong friendship with Bushnell. Olmsted would recommend Jacob Weidenmann, a Swiss-born landscape architect and botanist, to design and build the park. Weidenmann’s 1861 plan had a distinctive natural style, featuring smoothly sculpted contours and graceful paths, as well as informal clusters of evergreen and deciduous trees. After Weidenmann’s death, John Charles Olmsted took over advising at Bushnell Park, where he improved drives, terrace alignment, plantings, and various monument placement. After John Charles’ death, Olmsted Brothers continued working on Bushnell Park, with Edward Whiting and James Dawson taking over. Olmsted Brothers would continue work at Bushnell Park until 1947, where they would address regrading the site so a pond could be constructed.

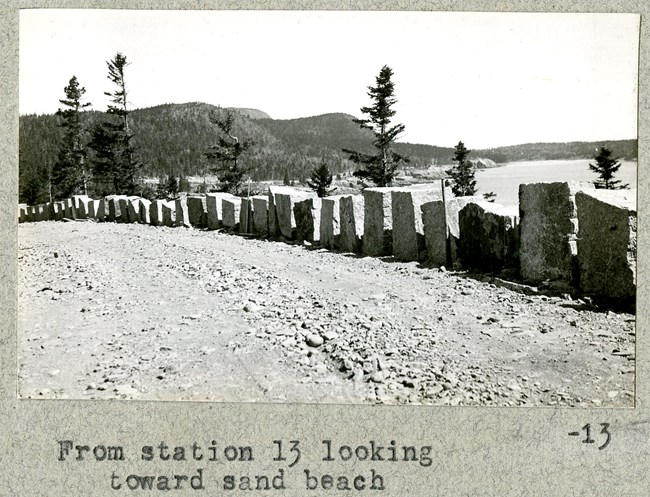

Olmsted Archives Acadia National Park (Mount Desert Island, ME)The idea of preserving portions of Mount Desert Island to be made into a public park was first proposed by senior Olmsted Firm member Charles Eliot. After Eliot’s untimely death, his father and Harvard University President Charles W. Eliot worked to secure the land donations to honor his late son.In 1916, the year Frederick Law Olmsted Jr.’s Organic Act would be signed into law, land in Mount Desert Island was acquired by the federal government. From 1908 until this point, automobiles were banned on the island due to a disagreement between permanent residents and summer visitors. Summer resident John D. Rockefeller, seeing the inevitability of automobile use in the park with increased visitors, would help finance a loop road that would keep automobiles off the carriage roads and away from the park’s interior. Olmsted Brothers joined the park in 1929 to recommend routes, locate scenic overlooks, and prepare engineering details for the loop road, with Olmsted Jr. taking the lead on this project. The National Park Loop Road Olmsted Brothers created provides automobiles access to numerous trails and attractions, like glacial lakes and Cadillac Mountain, the highest peak on the Atlantic Coast.

Olmsted Archives Camden Village Green (Camden, ME)In the late 1920s, after a fire had devastated a popular summer resort, a group of Camden, Maine patrons purchased the empty half-acre site and hired Olmsted Brothers to design a green for the village. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. would be the firm member tasked with leading this project.The patrons of Camden requested a simple, unadorned village green that would complement the land's awkward topography and lack of trees. Olmsted Jr. recommended the re-grading of the site, which would allow for a larger area of lawn that would be visible from downtown Camden. Trees and shrubs of various heights were also planted to shelter the green from neighboring buildings. What began with just a wooden fence evolved into rough granite posts with heavy chains, which are still present today. While Camden followed a majority of Olmsted Jr.’s plan, they did alter some of his recommended plantings. The people of Camden must have been pleased with the Olmsted Firm’s work, because twenty years later Camden once again hired Olmsted Brothers, this time to design a memorial flagpole to honor World War II soldiers.

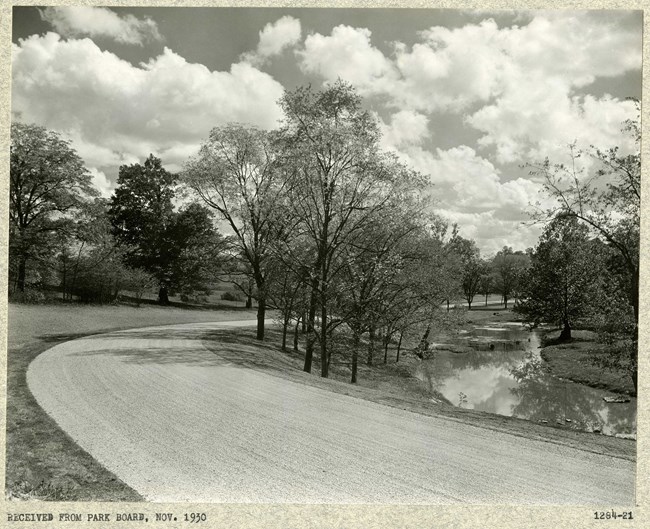

Olmsted Archives Seneca Park (Louisville, KY)In 1928, the Louisville Parks Commission purchased over 300 acres of land and hired Olmsted Brothers to begin designing Seneca Park. Two years after the original purchase, Parks Commissioners purchased the necessary land allowing Seneca Park to connect to Cherokee Park, which Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. had designed years before. Seneca Park would be the last park the Olmsted Firm designed in Louisville, but it would create a connected system of parks, allowing one to travel the city without ever leaving green space.Olmsted Brothers objective at Seneca Park was to designate different styled spaces for different activities. That can be seen through the layout of areas between the golf course, tennis courts, playgrounds, and other features. Not only are the features clearly defined, but they also utilize differing styles and variations of plants. Another notable design feature Olmsted Brothers included in Seneca Park, inspired by their father’s work at Central Park, was the separation of traffic. Not just on the roads but also in the 1.2 mile loop around the park, there is a clear distinction between pedestrian and automobile traffic to increase the aesthetic of the park, as well as the safety.

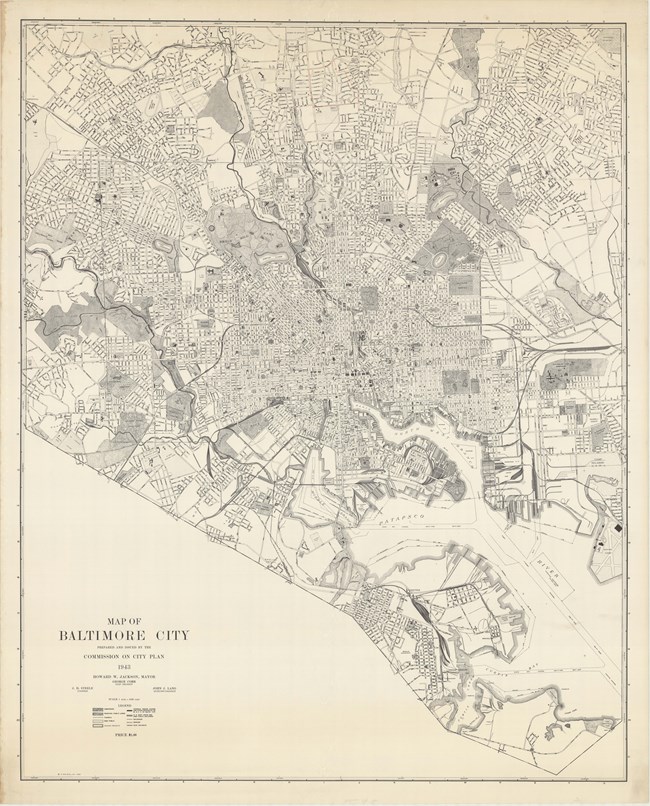

Olmsted Archives Baltimore City Plan (Baltimore, MD)In 1904, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was hired by the Municipal Art Society of Baltimore to produce a comprehensive plan for the public grounds around Greater Baltimore, creating a connected park system. For the next twenty years, Olmsted Jr. and other firm members would provide considerable assistance in specific park planning and land acquisition.Olmsted Jr. would also serve as landscape architect for residential communities and smaller green spaces in the Baltimore area. Additionally, Olmsted Jr. was instrumental in planning the reconstruction of Baltimore after the Great Fire of 1904; he would also help create the city’s Planning Department. Olmsted Jr., with the assistance of John Charles and firm members P.R. Jones and Percival Gallagher, Olmsted Brothers published The Report Upon the Development of Public Grounds for Greater Baltimore, where they stressed the need to treat parks as a connected system of green spaces. Olmsted Brothers’ plan has continued to shape Baltimore’s parks.

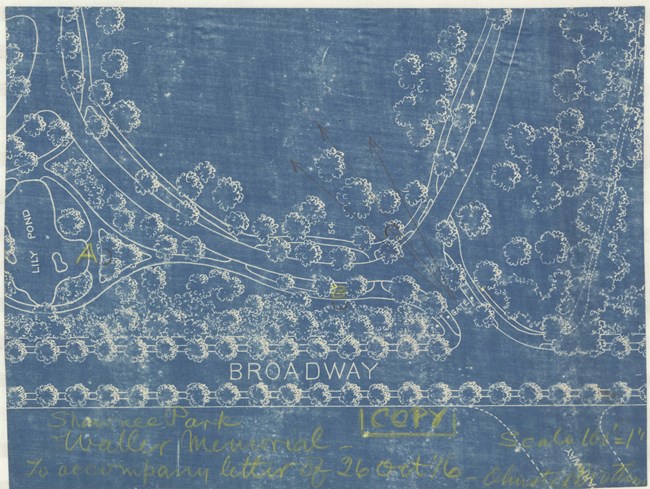

Olmsted Archives Shawnee Park (Louisville, KY)In 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted met with a small group of Louisville civic leaders and convinced them to create a park system. Louisville's leaders agreed, and Olmsted began working on his last park system. One of three large parks in the system, Shawnee Park is 180-acres of green space on a low-lying plain of river bottomland.Shawnee Park, just like Cherokee and Iroquois Park, took advantage of the topographical elements unique to the site. The park features a curving drive with border plantings encircling a 35-acre area, known as the Great Lawn, providing an ideal open site for recreation. With river scenery being a central design focus, the curving drive features five areas to view the river, with trees planted to frame these views. Additionally, beaches for swimming and a boat ramp for water access were developed, and Shawnee Park is the only of the Louisville system to have a formal garden. Shawnee Park would be the last of the three major Louisville parks Olmsted would work on, because much of the proposed land was privately owned by investors and it took years to acquire.

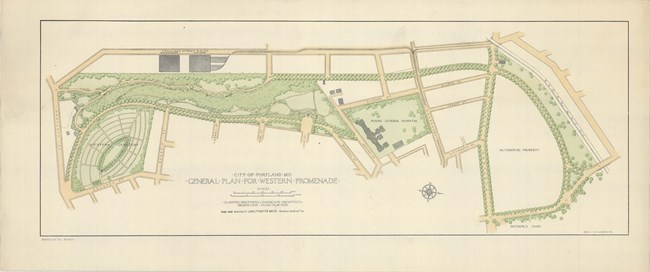

Olmsted Archives Western Promenade (Portland, ME)As early as 1836, Portland started acquiring land on the peninsula’s western bluff, as it had been known for its stunning scenery and views, as well as increased public pressure for open green space in the increasingly urbanized area. By the 1870s a tree-lined drive had already been built along the bluff, but it wasn’t enough for Portland’s residents.In 1905, Portland Mayor James Phinney Baxter hired Olmsted Brothers to design a landscape plan for the park, as well as to develop a master plan for all the city’s parks. On the Western Promenade, John Charles Olmsted led the design work, with firm apprentice Henry Vincent Hubbard assisting. In addition to improving the Western Promenade, Olmsted’s plan also connected the park to nearby green spaces, creating a park system modeled after Boston’s Emerald Necklace. On the Promenade’s twenty-five acres, Olmsted designed space for peaceful strolling and socializing by horse and carriage, though he didn’t include areas for structured recreation. Although Olmsted’s proposal for a formal plaza was not implemented, the Western Promenade’s strolling paths, lawns, and allées resemble the original design intention.

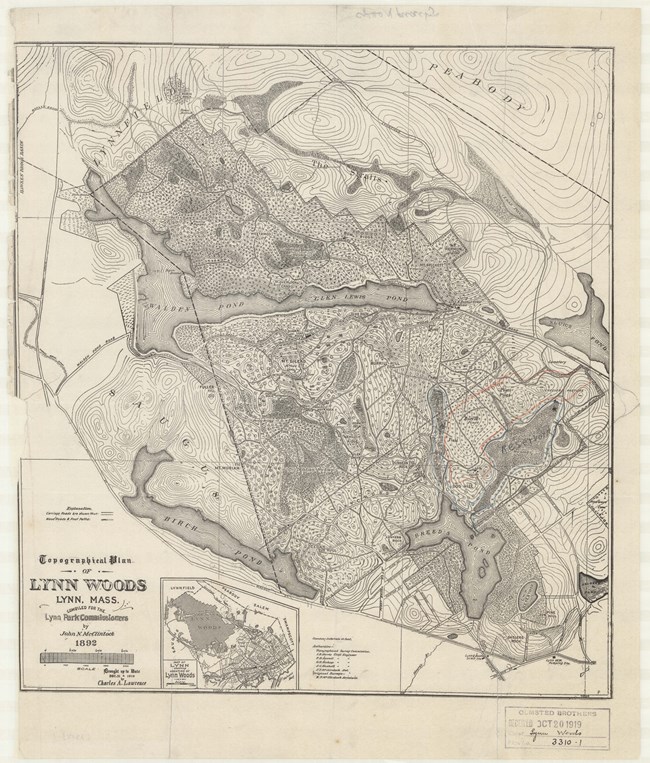

Olmsted Archives Lynn Woods (Lynn, MA)After damming a nearby pond, a group of Lynn recreationists formed a public trust to help preserve the local forest. By 1882, the state legislature had already passed the Massachusetts Park Act, enabling any town in the state to establish a park commission and acquire land.In 1889, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. was hired as a design consultant at Lynn Woods. In his recommendations, Olmsted stated that the area should be kept in its natural state as a rugged and wild forest. Design elements included in Olmsted’s design was a circuit system of carriage roads and walking trails. Additionally, Olmsted recommended street railway routes be extended, providing easy access to the woods for Lynn’s urban residents. As Greater Boston continued to grow, many scenic natural areas were being lost to development. By 1890, Lynn was one of the few communities in the area with protected municipal parkland. Olmsted firm member Charles Eliot praised Lynn for creating not only a large municipal park, but also a uniquely protected water supply. Describing Lynn Woods to the Boston Metropolitan Park Commission in 1893, Eliot wrote that “To-day the Lynn Woods embrace some two thousand acres, and constitute the largest and most interesting, because the wildest, public domain in all New England… Thus for the small sum of seventy thousand dollars the “city of shoes” has obtained a permanent and increasingly beautiful possession which is already bringing to her a new and precious renown.”

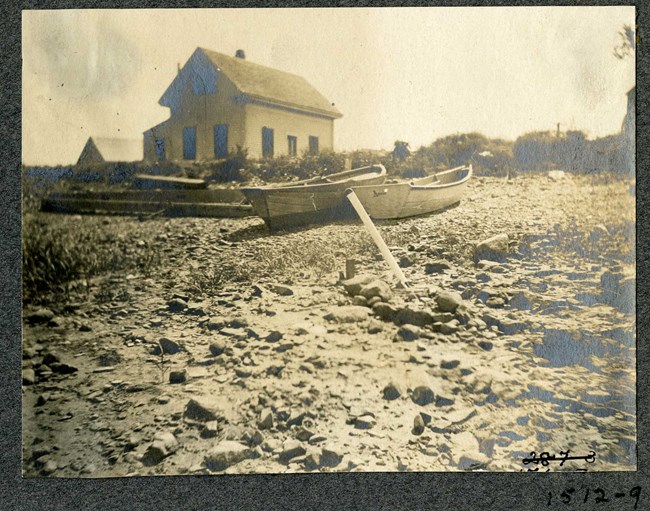

Library of Congress Cushing's Island (Portland Harbor, ME)In 1882, landowner Francis Cushing hired Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. to turn his 266-acres island into a summer colony. On the island, Olmsted found untamed natural beauty that needed no engineering to be perfected. Integrating design aspects Olmsted commonly used at parks and subdivisions, he chose to set aside idyllic places for common use.A year later Olmsted created his first report for Cushing Island, proposing the island shouldn’t be developed as a typical resort, which Cushing agreed with. Olmsted developed areas for recreational activities, as well as a network of walks and a curvilinear carriage drive, offering the best views of the ocean. Olmsted was able to seamlessly integrate a design for summer cottages with park planning. Despite much of his plan not being implemented, Olmsted’s road system was followed, as well as the large open areas he set aside and unobstructed ocean views.

Olmsted Archives Verona Lake Park (Essex County, NJ)In 1920, the Verona Park Association purchased land and surrounding acreage to form a 54-acre park. Olmsted Brothers were contracted to design the park, as part of their ongoing work for the Essex County Park Commission. Olmsted Brothers plans from 1922 incorporated a variety of passive and active recreation spaces, such as open lawns, hillsides for sledding, a beach, a sunken garden, scenic overlook, footbridge, playfield, concert ground, picnic grove and a boat house.By 1927, Olmsted Brothers had developed a new planting strategy for areas along the boathouse, comfort stations, and the bandstand, all of which were built and remain significant features of Verona Park today. Two years later, the historic dam was reconstructed along with a 36-foot footbridge. Olmsted Brothers submitted their final planting plan in 1932, which included lining commercial avenues with trees allowing for a separation of the park from more commercial zones. While actual development of the park did not start for several years due to court proceedings concerning condemnation of some land, this delay caused no inconvenience to the public, because the park was already being utilized for boating, bathing, skating, picnics, and band concerts. In 2008, rehabilitation efforts were carried out which made improvements to the park while maintaining the Olmsted firm’s overall design.

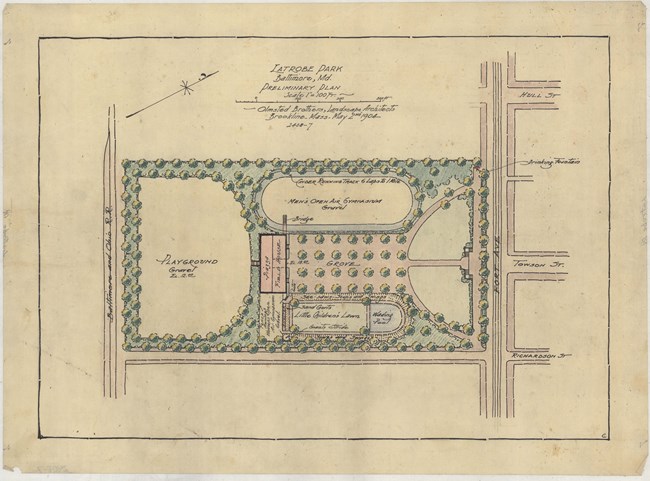

Olmsted Archives Latrobe Park (Baltimore, MD)Named after Baltimore’s mayor, Latrobe Park was established in 1902, located within the Locust Point neighborhood. Baltimore purchased six acres of land to create a park, hoping to serve the residents of this heavily industrialized area. Olmsted Brothers were soon hired to design the landscape, which would include playgrounds and venues for active recreation.Situated on land that slopes down, Olmsted Brothers chose to establish three distinct, generally flat areas, that would be separated by slight elevation changes. Primary access to Latrobe Park is along the northern border, lined with mature canopy trees. A brick and concrete staircase leads to a central promenade that traverses an open lawn. The center of Latrobe Park includes a grove of trees at the end of the central path which is flanked by playgrounds and open lawn. While this area once afforded views of the river, a dense tree canopy now screens the nearby highway and maintains the pastoral atmosphere of the site.

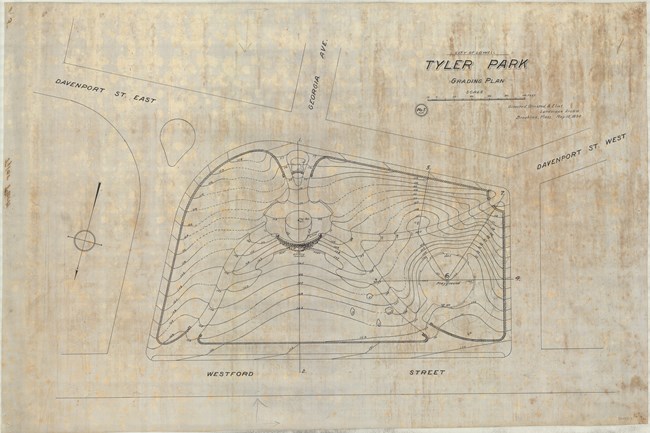

Olmsted Archives Tyler Park (Lowell, MA)In 1893, 2.74 acres of parkland was donated to the City of Lowell by the Tyler family, a wealthy family in the area hoping to see the land be used for a public park. Prominent Boston landscape architect Charles Eliot, not yet with the Olmsted firm, was hired to design the park. Shortly after beginning work, he partnered with the Olmsted’s, forming Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot.Tyler Park, which would become an important selling point for house lots in the area, was designed to take advantage of the area’s natural features. Eliot’s design included paths, a central fountain, and a play area for children. After Eliot’s untimely death in 1897, John Charles Olmsted continued to supervise work on the park. At Tyler Park, John Charles was disappointed in the construction, particularly the stonework of the central fountain, which would be dismantled in 1906 to make way for a rockery. Despite Eliot’s vision never fully being realized, much of his original design is still evident; the topography, trees and rocks, as well as original paths were all incorporated into the restoration work in the late 1990s.

Olmsted Archives Wood Island Park (Boston, MA)When looking at Frederick Law Olmsted’s work around Boston, the Emerald Necklace usually gets much of the attention. While the linear park would change Boston for the better, he had several other, smaller parks in the area that deserve their share of the attention.Wood Island Park in East Boston is one of these smaller, isolated parks. What started as a simple park featuring few walks and a playground transformed into his largest neighborhood park, with forty-six acres of public beaches, picnic areas, tennis courts, outdoor gymnasiums for both men and women, playgrounds, and several promenades. Despite Wood Island Park’s popularity, green spaces do fall victim to a community’s expansion. The northernmost jewel of the Emerald Necklace, and the glory of East Boston would be razed for the expansion of Logan Airport in the mid-20th century. There was a time when the park was ranked with San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park as one of the county’s great oceanside municipal parklands. Today, it sits under a runway for airplanes.

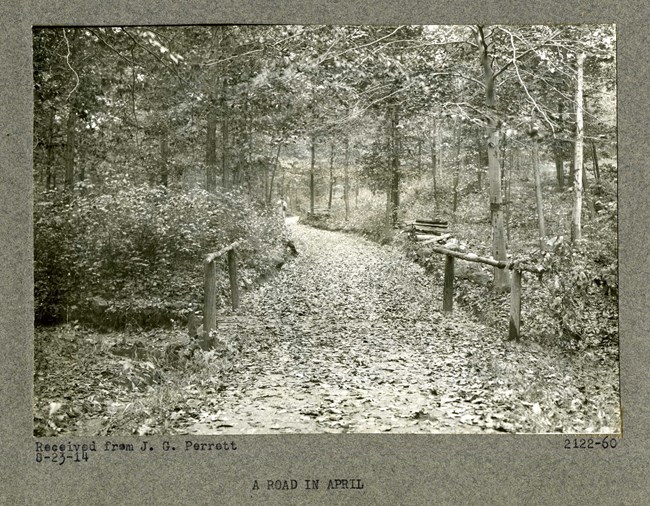

Olmsted Archives Middlesex Fells Reservation (Boston, MA)In November of 1880, the newly formed Middlesex Fells Association reached out to Frederick Law Olmsted, to see if he would advise and plan a four-thousand-acre rural park in the rocky hills north of Boston. Olmsted had already visited Middlesex Fells before, and drawing from that experience, noted the importance of “distinguishing characteristics of each particular property”.Olmsted agreed to help design the Fells, which came “from an appreciation of the beauty & use of absolutely wild sylvan scenery it is most desirable to avoid complicating the purpose of preserving and developing such scenery”. Regarding the topography of the area, Olmsted advised to “take it as it stands, develop to the utmost its natural characteristics, and make a true retreat not only from town but from suburban conditions” and that “every inducement should be offered visitors to ramble and wander about.” After retiring in 1885, Olmsted would stop work on Middlesex Fells. However, his protégé Charles Eliot began putting together the nation’s first metropolitan park system. After the park system was established in 1893, Charles Eliot included the Fells, with Olmsted Brothers continuing their landscape work in the Fells Reservation.

Olmsted Archives Marine Park (Boston, MA)Did you know that Boston’s Emerald Necklace isn’t finished as Frederick Law Olmsted intended? In 1876, Boston Park Commissioners wanted a waterfront park in south Boston to connect to Franklin Park via parkways. Located along Pleasure Bay, Marine Park, which forms a crescent looking out to Boston Harbor, was intended to be the final jewel of the Necklace, linking Roxbury to the ocean.In 1883 Olmsted published his preliminary plan for the park, showing a wooden pier at the Southern end of the park, with a tree-lined promenade leading to Fort Independence on Castle Island. A modified version of this plan was slowly constructed, however over time, the plans for the grand boulevard were never realized because it was too difficult to build over rail lines and acquire land from encroaching structures. Because of these difficulties, very little of the initial design survives and Marine Park was never fully integrated into the network of parks. In 1895, Boston’s official architect-built Head House, a resort, on the southeastern section of the island, though it was demolished in 1942. During the 1950s, Marine Park saw several alterations, including the construction of a permanent causeway at its north end, connecting Marine Park to Castle Island, enclosing Pleasure Bay.

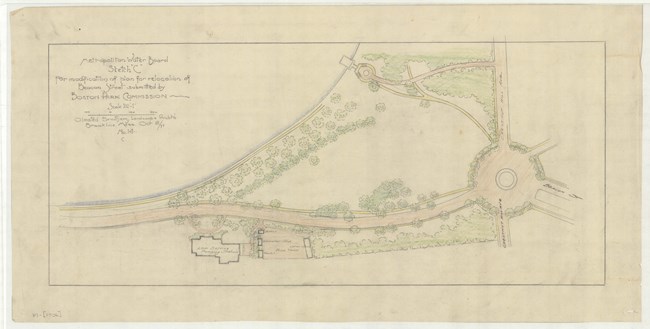

Olmsted Archives Chestnut Hill Reservoir Pumping Station (Boston, MA)Four years after his 1883 move to Brookline, Frederick Law Olmsted completed his first plan for improving Commonwealth Avenue, linking Beacon Street to the Chestnut Hill Reservoir. This created a loop with the previously laid out Chestnut Hill Driveway, which Olmsted dubbed the Chestnut Hill Circuit, but is also known as the Chestnut Hill Loop.In his 1887 plan for the Boston Park System, Olmsted believed the Chestnut Hill Loop would connect the Reservoir to other park areas in Boston. After the completion of Commonwealth Avenue, and a redesign of Beacon Street, Olmsted believed the Loop leading to the pleasure grounds at the Reservoir should be part of Boston’s municipal park system. After Olmsted Sr.’s death, Olmsted Brothers took over all his work. Olmsted Brothers produced plans for a courtyard in front of the Chestnut Hill Reservoir Pumping Station. Additionally, Olmsted Brothers performed the layout and grading for the proposed pipe yard site adjacent to the pumping station. The Chestnut Hill Driveway was one of the most popular pleasure drives in the Greater Boston area in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It inspired other cities, like nearby Cambridge, to create pastoral landscapes and pleasure drives around their municipal reservoirs.

Olmsted Archives Riverway (Boston, MA)The Riverway, part of the border between Boston and Brookline, is a linear park connected to Olmsted Park. A narrow park of 34-acres, the Riverway runs along the Muddy River, and was described by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1881 as “passages of rushy meadow and varied slopes from the upland; trees in groups, diversified by thickets and open glades.”The Riverway was added to the Boston Park System due to concerns regarding the pollution of the Muddy River. Falling into two distinct topographical sections, the area was graded and planted along the banks of the water. The design included a diverse collection of bridges, stairs, and park shelters. In addition to a bridle path, bridges helped separate those walking through park and on horse drawn carriage. While the Riverway may look like a natural landscape, the park is almost entirely constructed, including over 100,000 plants that weren’t in the area to begin with. Of the entire Emerald Necklace, the Riverway contains some of the most beautiful bridges done by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, the successor firm to Henry Hobson Richardson.

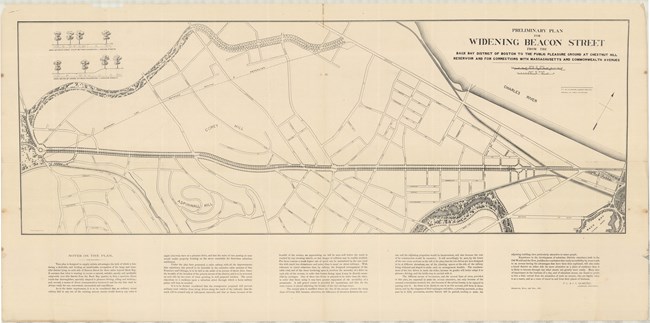

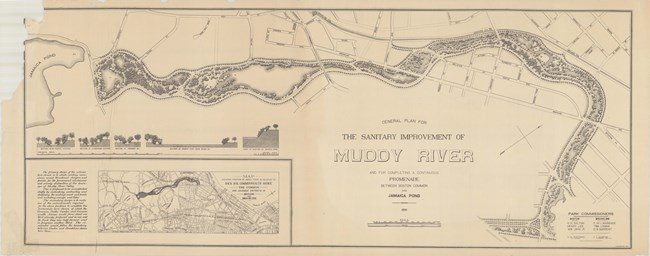

Olmsted Archives Muddy River (Boston, MA)Frederick Law Olmsted’s work on Boston’s Muddy River was born out of a sanitation need, not a park one. Engineering the clogged and polluted area, due to nearby development, was the priority for Olmsted. Starting by sculpting the waterway to create a gently winding stream, Olmsted was able to form a series of freshwater ponds in the area.Known today as Olmsted Park, the Southern section of the Muddy River extends from the natural kettle hole-shaped Ward’s Pond to the series of small pools in Willow Pond, and then to the large, man-made body of water at Leverett Pond. The Muddy River continues towards Back Bay Fens as a narrow, tree-lined waterway. While Muddy River appears natural, it is actually man-made. Olmsted chose to re-route the Muddy River to flow the Emerald Necklace. The corridor encompassing Muddy River became the linear park still in existence today. Olmsted’s vision of a linear park of walking paths along a gentle stream connecting numerous small ponds was complete by the turn of the century. Olmsted Archives Beacon Street Widening (Brookline, MA)Between Audubon and Cleveland Circle, the Brookline section of Beacon Street runs, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in the mid-1880s as a centerpiece for the urban development of the town. Olmsted’s design, which remains largely intact today, included a landscaped median for streetcar tracks, broad sidewalks and allées of trees.Of all of Olmsted’s early plans, “the Great Beacon Street Widening” was perhaps the one that most radically changed Brookline for the better. In 1886, Brookline Park Commissioners asked Olmsted to draw plans for widening Beacon Street to a two-hundred-foot avenue. As the fashionable Back Bay residential district expanded, widening Beacon Street was a logical extension. Olmsted was influenced by contemporary city planning in France; like the boulevards in Paris, Beacon Street was both the principal way to travel the district, and an avenue for pleasure driving, riding, cycling, and walking.

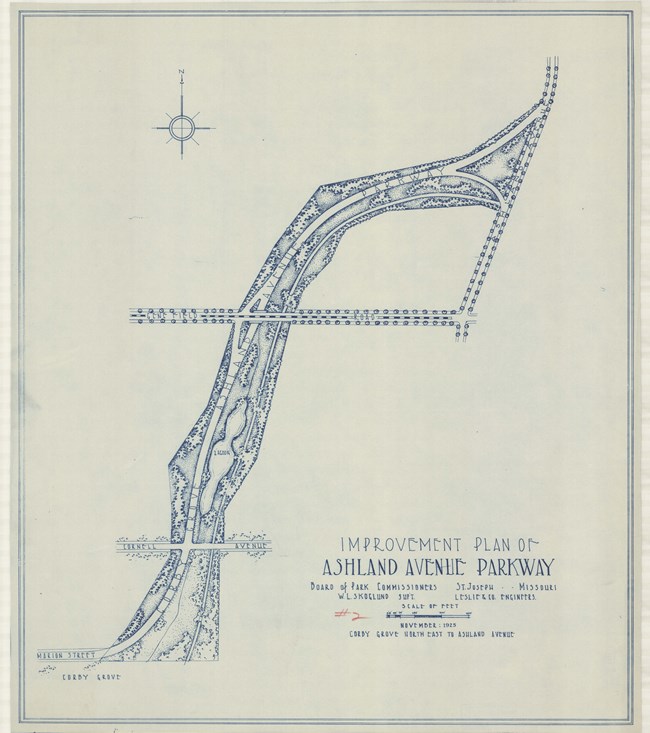

Olmsted Archives Saint Joseph Park System (St. Joseph, MO)In 1916, John Charles Olmsted made his first visit to St. Joseph, Missouri. While there was some correspondence in the years between, it wasn’t until 1925 that the park board formally hired Olmsted Brothers to review park development projects for the area. With John Charles involved in several projects across the country, it was firm member and architect Percival Gallagher who traveled to St. Joseph’s for several days.By April of 1925, Gallagher had sent a detailed report of his recommendations for St. Joseph, as well as a proposal for Olmsted Brothers to provide working drawings and supervise construction. Almost immediately after receiving this proposal, it was rejected, and another architect was hired to supervise the improvement of the park system. Olmsted Brothers were turned down because of their cost of construction; Olmsted and Gallagher calculated that they would need $30,000, while their competition only asked for $11,500. When it came to designing park systems, John Charles believed “A quiet drive or stroll in a large park, or in the country, with perhaps a family picnic under the trees, would be far more restful and therefore more rational than to rush off by train to some Coney Island pleasure resort, with its various artificial attractions.”

Olmsted Archives Kansas City Liberty Memorial (Kansas City, MO)Prior to the 1920s, Kansas City, Missouri, had erected few public memorials, however, the Liberty Memorial of 1925 was stylistically unlike the statues, plaques, fountains, and columns of earlier commissions. With close to 400,000 U.S. casualties of World War One, and 441 coming from Kansas City, their sacrifices were deserving of a structure that would stand for generations.Built on over forty-seven acres, the 217-foot-tall limestone-clad tower emits steam that, at night, is illuminated by red and orange light to create a flamelike effect. The central shaft is decorated with four sculpted figures symbolizing Sacrifice, Honor, Courage, and Patriotism. While the structure was completed by 1926, landscape work continued until 1938. Olmsted Brothers was hired to design the landscape of the Liberty Memorial, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr and Percival Gallagher taking the lead. Olmsted Jr. outlined a memorial with rows of maple and oak. At the Southern End of the memorial, there are two groves of trees with memorial plaques. Olmsted Brothers had recommended more elaborate planting plans, but they were never executed.

Olmsted Archives Eastside Park (Essex County, NJ)New Jersey’s Eastside and Westside Park are sister parks designed by John Y. Culyer and Frederick Law Olmsted Sr., respectively. Culyer, who was an assistant engineer on both Central and Prospect Park with Olmsted, was tasked with formally designing Eastside Park.Development between the two parks was unique. Both opened a design competition to determine its layout. The two most notable planners to submit designs were Olmsted and Culyer. Culyer’s design was chosen for Eastside Park, and Olmsted's was chosen for Westside. Culyer and Olmsted’s ideas were for the most part in sync. When Olmsted died in 1903, his legacy was incorporated into Eastside Park with the replacement of its naturalistic setting with intricate walkways of cobblestone and gravel laid out in organic fashion, providing a more formal landscape design.

Olmsted Archives Eagle Rock Reservation (Montclair, NJ)While the Olmsted firm made their first report for Essex County parks in 1884, praising the scenic opportunities of the Eagle Rock area, it wasn’t until 1898, when the firm had been renamed Olmsted Brothers, that a guide for developing the area as a reservation was put forth. John Charles took lead on this project, working with engineers to plan well-graded but subtle drives, bridle paths, and trails throughout the steep slopes and valleys.John Charles recommended planting hemlocks and pines to enrich the boldness of the valley, with native rhododendrons, laurels, and ferns used as texture for the trails. Shelters were placed around the park for people to stop and capture stunning views across the river, using stones as walls to blend naturally. Spanning over 400 acres, Eagle Rock Reservation was left wild except for its overlook of Manhattan. John Charles Olmsted helped provide the area with a nuanced landscape plan, which would maintain the existing maple and red oak woodlands while supplanting some existing species with pine and hemlock.

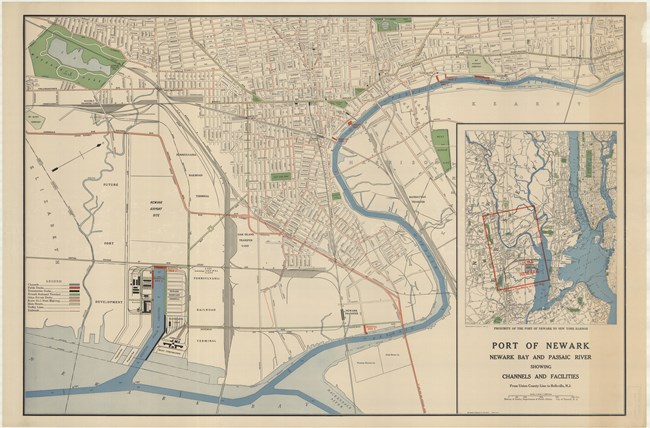

Olmsted Archives Essex County Park System (Essex County, NJ)After their work on Central and Prospect Park, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were invited to Newark, New Jersey in 1867 to explore potential parkland around the area. The first park the pair would develop in the area would be Branch Brook Park, due to its scenic potential.Olmsted and Vaux had originally proposed acquiring a 420-acre tract, though the county rejected the land acquisition, which would be too costly for a single park. At the same time Essex County rejected the proposal, Charles Eliot’s concept for a metropolitan-based park system had just emerged in Boston, giving Essex a feasible model to base their work off. In 1895, the Essex County Park Commission again reached out to the Olmsted firm, though this time it would be John Charles Olmsted of Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot who took lead on the project. John Charles submitted a comprehensive report to the Commission, detailing both the public health and economic benefits of a park system. In the end, the Olmsted plan of a network of connected parkways was only minimally implemented, with most of the land being acquired by state highways. Despite this, by 1895 20 of the 26 parks and reservations in Essex County were designed by the Olmsted firm.

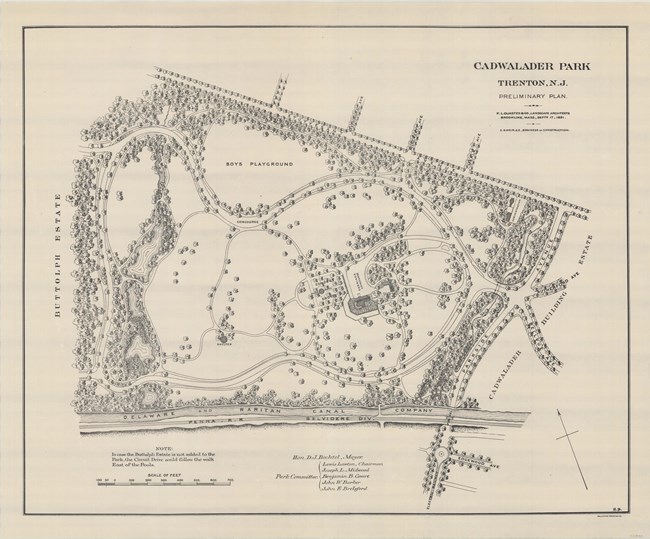

Olmsted Archives Cadwalader Park (Trenton, NJ)Frederick Law Olmsted visited Trenton, New Jersey in April of 1891 to view the proposed site for Cadwalader Park, determine if it was suitable and take the job, all of which he did. It would become Olmsted Sr.’s last great urban park. Olmsted’s plan for Cadwalader Park relied on the creation of long open views and rolling meadows that contrasted with the more densely planted edges of the park.Design proceeded rapidly with John Charles Olmsted assisting with supervision of the park. The first changes at Cadwalader involved a looping carriage drive, pathways, and plantings. The mansion that had been on the property, the focal point of the design, was repurposed into a refectory. A vine covered terrace and concert grove complemented the refectory, providing outlooks to the lawn beyond. Park progress continued to follow the broad outlines put in place by Olmsted’s plan, however, monuments and zoo enclosures were placed into the pastoral landscape against the firm’s recommendations. By 1892, political changes in Trenton resulted in decreased support for the parks, ending Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.’s work on Cadwalader Park.

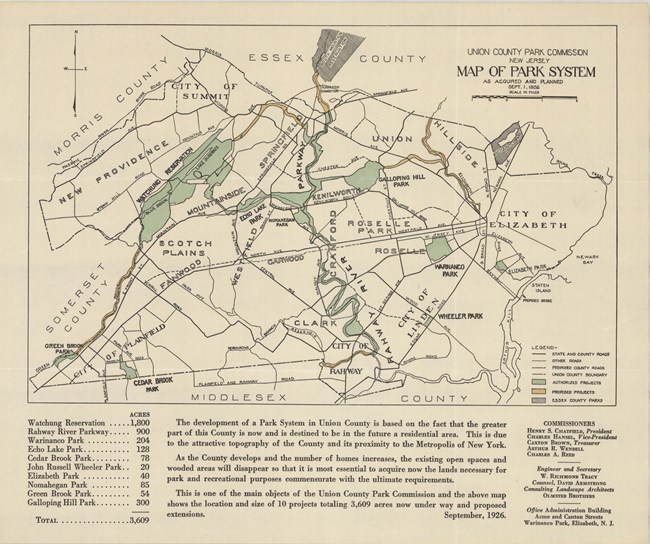

Olmsted Archives Union County Park System (Union County, NJ)By 1921, Union County’s population had surpassed 200,000 and was in need of park space, and a commission to help acquire the land needed. After forming the Union County Park Commission, Percival Gallagher of Olmsted Brothers was quickly hired to perform a countywide reconnaissance, evaluating the area’s potential for an expansive network of parks and riverside corridors, linked through cross-country parkways.Just as Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. would have done, Gallagher proposed setting aside land for both passive and active recreation. The Olmsted firm’s plan was to create several large park units that would serve the entire country, as well as smaller parks to serve local communities. In their 1921 proposal, Olmsted Brothers wrote that “The attractiveness of much of the County, therefore, is to be found in its pleasantly undulating topography and the quiet pastoral character of the countryside, in which the chief details of lively interest are the many streams of water and ponds along their way. These streams and ponds, under the circumstances, become particularly important in any consideration of the natural physical features of the country.” Despite passing away in 1934, Gallagher shaped a remarkably varied park system consisting of both urban and suburban parks, a mountain reservation, and parkways. Upon Gallagher’s passing, the Union County Park System paid tribute to his “wide vision, far-flung experience and high knowledge of the beautiful and the practical.” Olmsted Brothers, and later Olmsted Associates, continued advising the Union County Park Commission well into the 1960s.

Olmsted Archives Rahway River Park (Union County, NJ)Upon the creation of the Union County Park System, Park Commissioners engaged Olmsted Brothers to create a county-wide park system. In addition to urban and suburban parks, the park system also included a reservation and a series of parkways along Elizabeth and Rahway River.Rahway River Park was developed by Olmsted Brothers firm partner Percival Gallagher from 1921 to 1929. Rahway River Park, and all the parks in the Union County Park System got their inspiration from their neighbor, the Essex County Park System, also designed by the Olmsted firm. Rahway River Park is one of the four neighborhood parks in the entire Union County Park System. At the end of Olmsted Brothers’ involvement, a pool and bathhouse were being constructed on the southwestern section of the park. Installed by the Works Progress Administration, the swimming pool was among the first such pools in a public park in the United States.

Olmsted Archives Lake Weequahic Reservation (Essex County, NJ)In 1895, the newly formed Essex County Park System proposed developing a park in Southern Newark. By 1889, the Essex County Park Commissioners had purchased 265 acres of land in 12 different parcels. Additionally, the Waverly Fairgrounds horse trotting track was also acquired.Olmsted Brothers, led by John Charles Olmsted, were hired to transform the mosquito-ridden Weequahic Lake and its surrounding land into a naturalistic landscape with broad lawns, forested groves, and an 80-acre lake. Finishing his plan in 1901, Weequahic Park was influenced by the City Beautiful movement, which originated at Frederick Law Olmsted Sr.’s design of the World’s Columbian Exposition of Chicago in 1893. In addition to the lake, Weequahic Park contains various pavilions, structures, and sports facilities like the now demolished grandstand, a half-mile racetrack, a golf course and tennis courts. A residential neighborhood developed along the western edge of the park with architecturally significant middle-income housing and mansions.

Olmsted Archives Watertown Park (Watertown, NY)Olmsted Brothers were contacted in 1899 by John C. Thompson, president of the New York Air Brake Company, about anonymously gifting a park to his city of Watertown, New York. Thompson’s office was in New York City, so he was already familiar with the work of the Olmsted firm. John Charles Olmsted took the lead on the design for the park, originally called Watertown Park.On his first visit to the area on June 7th, 1889, the Watertown Daily Times reported that “John C. Olmsted, of Brookline Mass., the designer of the city’s projected park, is now in Chicago, looking after some landscape work there of which he has charge. On leaving there he will come directly to this city to make such changes in his designs as he deems advisable after inspecting the park as preliminary staked out. He is expected here the last of the week or the first of the next, and will probably remain several days. He will visit here frequently during the progress of the work.” John Charles started by acquiring more than 700 acres of woods and fields that would provide scenic vistas over the growing city, leading towards Lake Ontario. An addition to part of the park plan was contiguous land for a residential development. John Charles produced his first plan for Watertown Park in 1901 and would spend the next two decades supervising construction at the challenging, rocky site. The plan for Watertown Park included a formal tree-lined boulevard as the primary entrance, which would connect roads and paths curving through the park towards its summit. To mitigate the steepness, John Charles designed walls, overlooks, shelters, and steps that ascended the slopes, all accompanied by textured plantings. Upon Thompson’s death in 1924, his anonymity was taken away, and the park was renamed to Thompson to honor its founder.

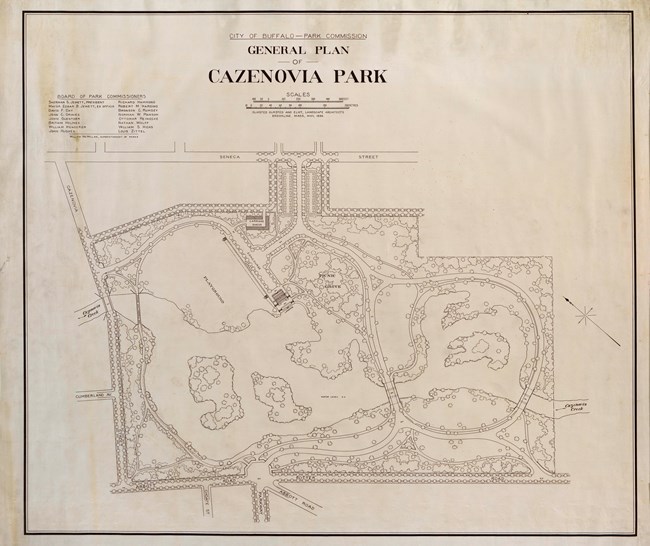

Olmsted Archives Cazenovia Park (Buffalo, NY)In 1889, the City of Buffalo asked F.L. Olmsted & Co. to recreate the success the firm had in the northern park system and continue developing parks in the southern part of the city. While Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. suggested a single lakefront park, Buffalo Park Commissioners instead purchased two inland sites in 1891, one of which would become Cazenovia Park.In April of 1892, Olmsted submitted his design of Cazenovia Park. 76 acres of low, fertile land that had previously housed a village of Seneca Tribe’s Buffalo Creek Reservation would now become parkland. Handling the problematic seasonal flooding of the area, Olmsted, who developed plans for Cazenovia Park from 1892 to 1896, proposed damming the creek to create a 20-acre lake with three islands and a boathouse overlooking the water from the north. By August of 1892, construction on Cazenovia Park had begun. The principal features Olmsted designed for the park was a large play area, a winding drive that would cross a stream, and pass through the park overlooking the playground. Additionally, there was a grove of trees for concerts and a large shelter house.

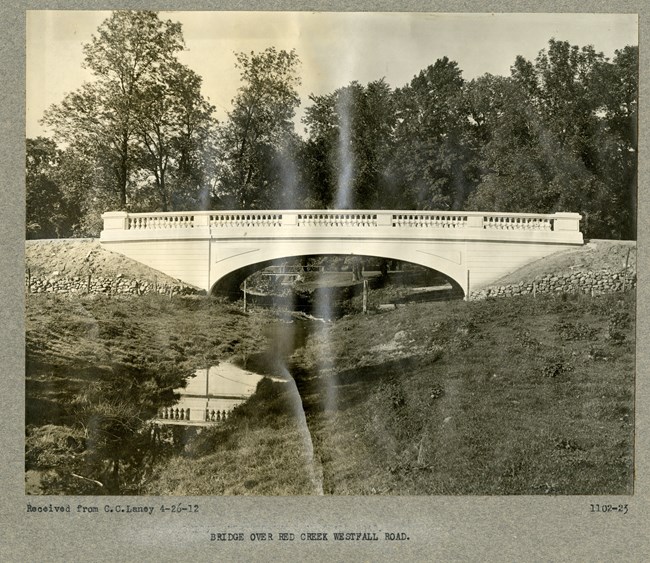

Olmsted Archives Genesee Valley Park (Rochester, NY)Part of the Rochester Park System, which Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. and his successor firm designed from 1881 to 1912, Genesee Valley Park was originally named South Park. Divided by the Genesee River, Olmsted chose the 543-acre site for its ability to naturally incorporate water with wooded, rolling terrain. Despite five years of public opposition to the park, the Board of Park Commissioners exerted considerable pressure on Olmsted to make recommendations and begin his landscaping work.Olmsted wrote that any advice on how to utilize the land was dependent on the topography of the site. He deliberated over designs, preferring to study topography and other aspects of the land before making a final decision. In the end, Olmsted’s design included land bordering both sides of the Genesee River. On the West side of the river, recreational facilities were placed while on the opposite bank, there was a pastoral setting that included a meadow, deer park, and picnic groves encircled by carriage routes. Between 1889 and 1898, 62,500 trees were planted, while shrubs and willows were rooted along the riverbanks and within the woods. John Charles Olmsted would assist his father at Genesee Valley Park, overseeing the placement of additional recreational facilities, including a golf course. In 1908, a donation of 120-acres expanded the park, though when it was divided by the Erie Canal in 1908. Olmsted Brothers mitigated the damage to the site by creating a bridge that reunited the landscape.

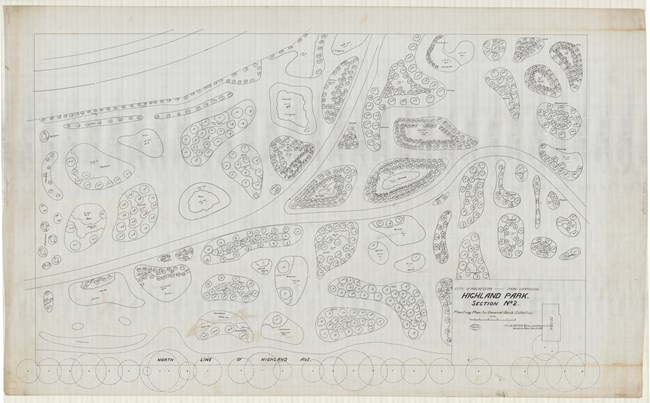

Olmsted Archives Highland Park (Rochester, NY)F.L. & J.C. Olmsted were hired by the Rochester Parks Commission to design Highland Park, with the intention to turn it into an arboretum. Frederick Law Olmsted chose to create a picturesque park that incorporated the nearby city reservoir and afforded scenic views of Rochester. Highland Park sits by Pinnacle Hill, the highest point in Rochester, which Olmsted planted with pine trees and shrubs.Though planned and planted as an arboretum, Olmsted expertly designed Highland Park to seem like a natural occurrence of trees, shrubs, and flowers. Originally, Olmsted wanted nothing to do with this park. The area didn’t have any water features often featured in his landscapes, though Olmsted had already agreed to design Rochester’s Parks, and that meant all of them. In 1902, John Charles Olmsted visited Highland Park to view the new gatehouse at the reservoir. John Charles objected to the addition due to its blocking of the sidewalk. Regardless of his dislike, John Charles was unable to change the plan as work had already progressed too far. John Charles also objected to the use of pale, yellow brick, seeing it as out of harmony with the park scenery.

Olmsted Archives South Park (Buffalo, NY)South Park would be the second phase of work done on the Buffalo Park and Parkway System, designed by F.L. Olmsted & Co., the successor firm to Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot. Located a mile inland of Lake Erie, the land that would become South Park was purchased in 1891. The 156-acres of marshy farmland boarded by railways and industrial sites was composed in a roughly rectangular shape.In early 1893, Frederick Law Olmsted provided the Buffalo Board of Park Commissioners with a design for South Park, the second of two new parks to be constructed in the southern section of Buffalo. Designed like an English landscape garden, South Park features a 22-acre lake with three densely planted islands flanked by a gently rolling meadow, with the whole park encompassed by a circuit drive and network of footpaths. Running along the western and northern sides of South Park were railroads with multiple tracks, which Olmsted noted ““raised upon high embankments so that the trains are in full view from almost every part of the park, and the noise and smoke of the locomotives will always detract from the pleasure and healthfulness of a visit to the park.” Between 1894 and 1910, trees adorning the pastoral landscape of South Park were planted. Of Olmsted’s many urban and picturesque water features in parks, South Park’s lake is considered one of the finest examples.

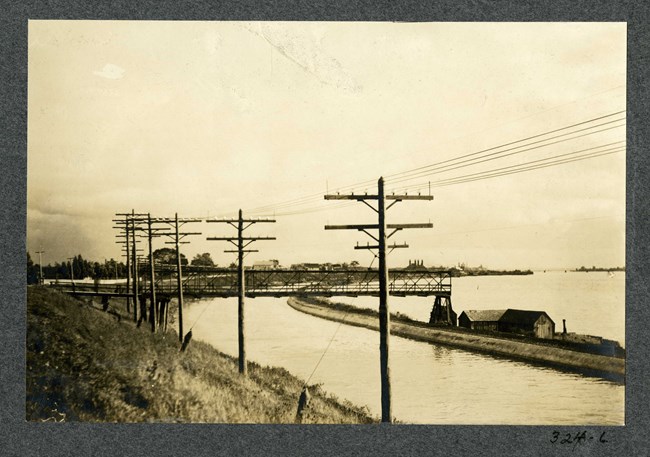

Olmsted Archives Riverside Park (Buffalo, NY)The final Olmsted designed park in Buffalo, New York, Riverside Park, is the city’s northernmost park. Established in the late 1880s as a private picnic ground termed Germania Park, Olmsted Brothers created their design in 1898. Encompassing twenty-two acres, Riverside Park overlooks the Erie Canal and Niagara River.Olmsted Brothers brought to fruition their father’s long-held vision of a waterfront park. Riverside Park was Buffalo’s first Olmsted designed park with a direct waterfront connection. In their design, Olmsted Brothers chose to restrict planting along Riverside Park’s western edge, providing extensive views along a particularly wide section of Niagara River. The design for Riverside Park has suffered considerably from intrusions and neglect since the Olmsted’s worked on it. A senior citizens center, an ice rink, and a set of swimming pools cover much of the formal area of the park, blocking views to the river. The noise from the Niagara Thruway has also caused a significant noise distraction in the park.

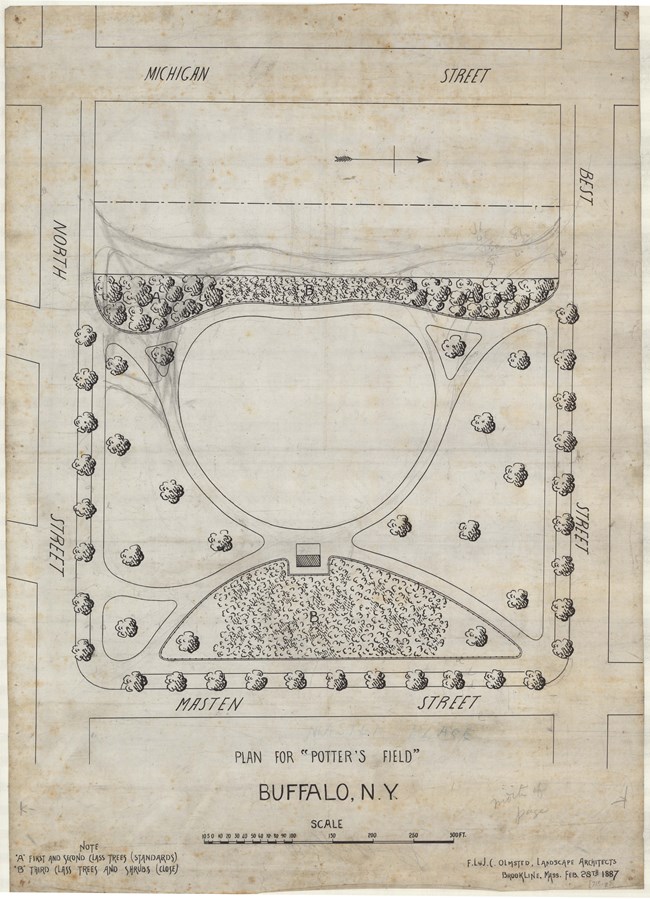

Olmsted Archives Masten Place (Buffalo, NY)In April of 1887, Frederick Law Olmsted submitted his designs for several parks falling under Buffalo’s Board of Park Commissioners control. Included in those plans was the design for Masten Place, which would be constructed on what was then Potter’s Field, a burial ground for Buffalo’s lower class. Construction of Masten Place began in the Spring of 1887 and was substantially completed that same year.Olmsted’s design for Masten Place called for winding diagonal walks ten feet in width crossing the site from its corners, leaving an open turf playground area at the center. During the construction process, the site required considerable regrading to make it suitable for park purposes. Characteristic of similar Olmsted parks, thick plantings screened the site from the bustle of street traffic. In 1895 Masten Park became the focus of considerable local controversy when it was proposed as the site of a new high school. Despite strong opposition from Buffalo Park Commissioners, the school was built at the center of the plot. Although the new building destroyed its continued suitability as a public pleasure ground, the remainder of the site remained in the charge of the Park Board.

Olmsted Archives Downing Park (Newburgh, NY)Downing Park, the final collaboration between Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, was created out of the two men’s love for their mentor: Andrew Jackson Downing. Newburgh, New York offered the commission to Olmsted and Vaux, who delivered their plans in 1889. The pair provided their design for free, on the condition that the park be named after their mentor, who had lived in Newburgh.Olmsted and Vaux had already gained prominence for creating open spaces that promote well-being of the public, favoring naturalistic, rustic, and curving landscape designs. Olmsted and Vaux brought everything they’d learned through their partnership to Downing Park, like “circulation”, which landscape architects describe as a sense of continual discovery. Originally, Downing Park was to lay on a hillside, however Olmsted convinced Newburgh Park Commissioners to add the nearby flat land, providing land to create Polly Pond and grassy meadows for family picnics and larger community events. Walking through Downing Park today, visitors enjoy changing views of varied natural features. Many of the trees present today were originally planted by Warren H. Manning, Superintendent of planning for the Olmsted firm. Not only would Downing Park be the final collaboration between Olmsted and Vaux, but it is also the only known commission where both their sons, John Charles Olmsted and Downing Vaux, assisted in the design.

Olmsted Archives Iroquois Park (Louisville, KY)Addressing the Salmagundi Club, a small group of Louisville civic leaders, in 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted wanted to further their interest in establishing a park system. As a result of this meeting, the Louisville Park Commission was formed to create a network of parks and boulevards, the last major park system of Olmsted Sr.’s career.Three large parks would anchor the system along the city’s perimeter, with Iroquois Park, laying at the Southern edge. Louisville’s mayor Charles Jacob personally purchased the property that Iroquois Park would sit on. For Iroquois Park, Olmsted envisioned a scenic reservation on a rugged, steep, heavily wooded hillside. Built on 739-acres, Iroquois Park is the largest in Olmsted’s Louisville Park System. The hillside Iroquois Park sits on is covered with an old-growth forests, prompting Olmsted to call it “Louisville’s Yellowstone”. Olmsted designed paths through the park to dramatize the forested landscape to achieve changing, panoramic, scenic vistas from overlooks. |

Last updated: June 15, 2024