|

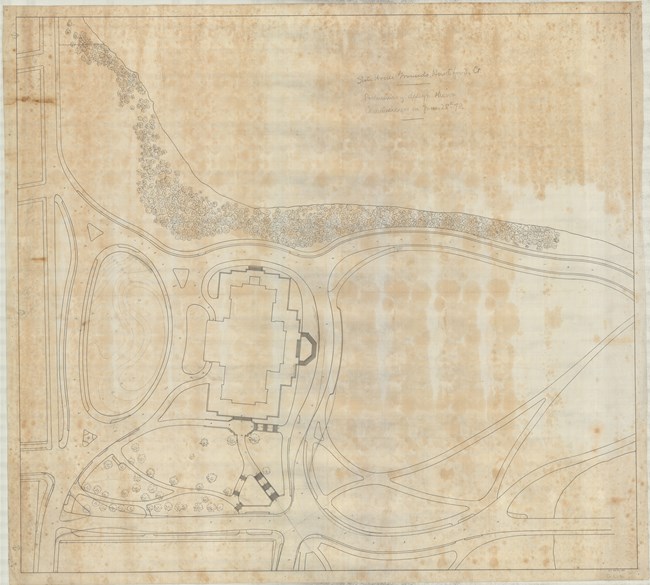

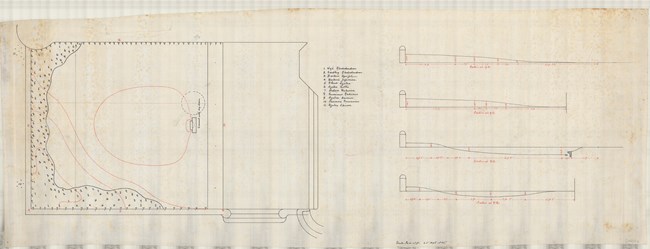

The Olmsted firm’s landscape work for public buildings spans about 100 years. The nineteenth century planning for public buildings by Frederick Law Olmsted was characterized by its curvilinear grace, stately proportions and firring enhancement for the structure to be served. In the City Beautiful period, the firm designed grounds of public buildings with more axial formality, to serve as decorative anchors for the municipalities. Later, in the 1920s and 1930s, civic enrichments were often memorial projects (such as the Newton City Hall and War Memorial in Newton, Massachusetts, or the Robbins Memorial Town Hall in Arlington, Massachusetts). Regardless of style, the Olmsted firm maintained a notable design aesthetic, which gave dignity of setting to projects large and small. The work for public buildings from the Olmsted Associates era (1962-1979) was less extensive, consisting of consultations on earlier projects with some new library work (such as the West End Library Branch in Boston, Massachusetts, and the Rice Library in Kittery, Maine). The practice of the Olmsted firm included about 150 listings for the grounds of public buildings of all types, of which approximately 100 generated at least one plan. The largest group in this category is the group of libraries (about 34 listings), followed by projects for municipal buildings such as city and town halls (15 listings), civic centers (11 listings), court houses (3 listings), and utilitarian structures such as incinerators (3 listings). Museums and various art-related institutes account for another twelve listings, many of which were projects that generated a considerable amount of work over several decades, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Cleveland Art Museum. However, the most prominent sub-type within this thematic category is the work done for capitol buildings (11 listings), the oldest and most notable being the iconic design for the United States Capitol begun by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1874, a project that actively continues to the first decade of the twentieth century. Also beginning in the 1870s, the firm planned the New York State Capitol, a design collaboration of Frederick Law Olmsted and architects H.H. Richardson and Leopold Eidlitz; as well as Bushnell Park abutting the Connecticut State House in Hartford. The successor firm of Olmsted Brothers continued to work on state capitols, its most prominent commissions being those for the grounds of the Washington Capitol at Olympia, the Kentucky Capitol at Frankfort and the Alabama Capitol at Montgomery. Smaller projects included more limited work for the Utah Capitol in Salt Lake City, the Maine Capitol in Augusta, the North Carolina Capitol at Raleigh and the Pennsylvania Capitol at Harrisburg, as well as other states where the firm was consulted about capitol work. There are various miscellaneous but important public building projects included in this thematic category, such as planning for the White House in Washington, D.C., or for the Maine Governor’s Mansion in Augusta; and for military establishments such as the Armory in Ansonia, Connecticut, the Schuylkill Arsenal in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, or the Jefferson Depot in Jeffersonville, Indiana, where Frederick Law Olmsted again worked with Montgomery Meigs, who had directed some of the United States Capitol Construction. The emergency wartime planning that engaged much of the time of Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. during 1917-1918, and in which many of the firm’s apprentices were involved, was for the United States War Department to plan military cantonments and bases for the armed forces rapidly deployed as the United States entered World War I. There are several caveats that should be understood in the consideration of entries in this and other thematic categories. For example, there are numerous crossovers in the references for projects such as the White House. While this project seems to indicate only three plans, all from 1903, many other plans and documents were prepared in the 1930s as a component of the extensive multiple-project planning for the Fine Arts Commission in Washington, D.C., labeled for “the Executive Mansion,” and found in the category Miscellaneous Projects. Additionally, some of the public building work came about as an element in more extensive and varied planning within a community, sometimes sponsored by a particular patron, such as Mary Curtis Bok for the Rockport Library in Rockport, Maine, and the Camden-Rockport Information Bureau in Camden, Maine. Therefore, the researcher must consider creative linkages when exploring these various categories and look for references for any project under other project listings in a location or under a sponsor. Text taken from The Master List, written by Arleyn A. Levee Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

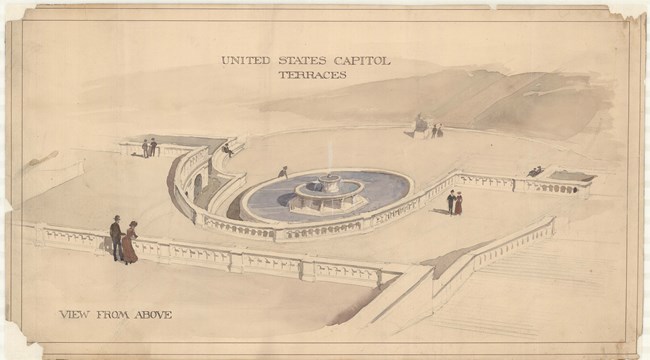

Olmsted Archives U.S. Capitol Grounds (Washington, D.C.)The Capitol we see today underwent extensive expansion in the mid-19th century, and who else to plan and oversee that work but Frederick Law Olmsted. In 1874, with the additions of House and Senate wings, as well as a new dome, the grounds surrounding the Capitol also needed to be enlarged. Describing his plan for the Capitol, Olmsted said that “the ground is in design part of the U.S. Capitol, but in all respects subsidiary to the central structure.” To not detract attention away from the Capitol Building, Olmsted was careful not to group any trees or other landscape features together. He also strongly believed that the use of sculptures and other ornamentations should be kept to a minimum. While Olmsted was determined to have the grounds compliment the building, he also felt the need to address architectural problems that had persisted for years. Washington, D.C. was expanding west, and the terraces of the Capitol Building did not seem to support that notion. Olmsted proposed marble terraces on the sides of the building to “gain greatly in the supreme qualities of stability, endurance, and repose.” Work accelerated in 1877, both on the building and the grounds. Olmsted employed over 100 varieties of trees and bushes at the Capitol, with thousands of flowers used in seasonal displays. In 1878, after hundreds of flowers had been destroyed or stolen by vandals, watchmen were appointed to patrol the grounds and proved quite effective, allowing the lawns to be completed. In 1885 Olmsted retired as superintended of the terrace project, though he continued to direct work on the grounds until 1889. His goal in working on the Capitol was not to detract from the building but compliment it with the grounds. He did so by contrasting the buildings straight lines with the curved walkways of the grounds, the same grounds a bill must walk in the hopes to become a law.

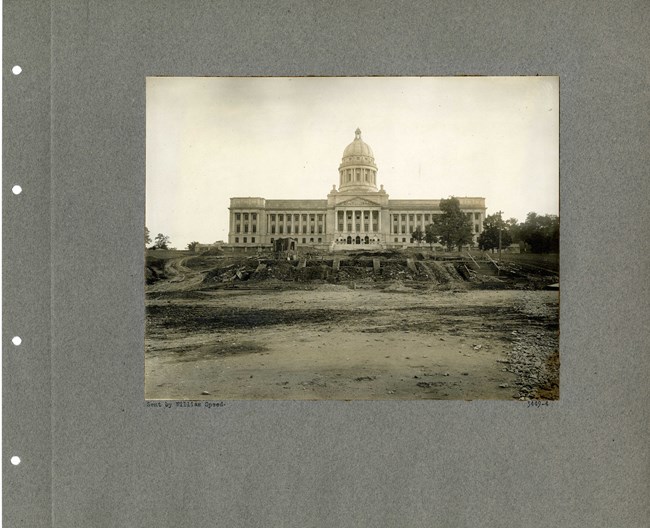

Olmsted Archives Kentucky State Capitol (Frankfort, KY)The Kentucky State Capitol building sits along thirty-four acres of the Kentucky River. While Ohio architect Frank Andrews designed the building, the grounds were left to Olmsted Brothers, making it one of the eleven capitol buildings the Olmsted firm worked on.Receiving over one million dollars in federal funds, as reparations for damages suffered during the Civil War as well as compensation for services rendered during the Spanish-American War, Olmsted Brothers began their involvement on the project in 1905. Between 1908 and 1910, Olmsted Brothers generated several plans for the Kentucky State Capitol, before its completion in 1910. Like other capitol buildings the Olmsted firm had worked on, the Kentucky State Capitol was situated on a peninsula overlooking a hill. The neoclassical building is oriented on a north-south axis and set on a pedestal rising above a paved terrace, allowing for expansive views. The Kentucky State Capitol is nestled within expansive sloped parkland, with trees all along the perimeter. Renovations in 1984 led to the reestablishment of the original Olmsted design, including a circular entry drive and brick terraces surrounding the building. As with many Olmsted-designed landscapes being reworked, the plans stored at Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site were crucial to its completion.

Olmsted Archives Newton City Hall (Newton, MA)While designed under the Olmsted Brothers firm, Newton City Hall was directed by Henry Vincent Hubbard, a firm employee, starting in 1931. Once clients, architect, and landscape architect agreed on a plan for the layout of the site, Hubbard then advised on an exact location for the building, as well as all matters relating to the grading, planting, road construction, or supervision of the site.Hubbard’s design for the grounds of Newton City Hall was elegant and dignified, fitting for the grand Georgian Revival building it surrounded. Hubbard turned the existing swamp and brook at the east end of the site into a link of picturesque ponds, offering dramatic reflections of the building. Debates between the City, architects, and Hubbard about how to maximize that reflection of City Hall in the water came up. Throughout the project Hubbard pressed for the creation of a basin and spillway to retain sand and silt, preventing the water from getting clogged. Although the city considered the idea, no basin was constructed. The landscape composition, which called for an expansive open lawn, was segregated from its surrounding by borders of trees and shrubs. Carefully planned vista openings were implemented, allowing framed views of City Hall and the nearby War Memorial. Hubbard described the area around Newton City Hall as “simple but dignified and impressive”, with open lawns, specimen elms, formal pathways, and evergreen plantings enhancing the dominance of the building.

Olmsted Archives Cleveland Art Museum (Cleveland, OH)In 1925, Garden Club of Cleveland hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. of Olmsted Brothers to beautify the parkland surrounding the city’s Museum of Art. When describing the Fine Arts Garden his firm would produce, Olmsted Jr. stated “I know of no other example of landscape art as beautiful as this where such a large part of the population pass daily and enjoy it”.Work on the ground at the Cleveland Museum of Art was left to firm members Edward Clark Whiting and Leon Zach. The key feature of the grounds was the Fine Arts Garden, framed one both ends by the lagoon. Other features include tree groves and walkways. The formal garden consists of two outdoor rooms that travel along a central axis bookended by the museum’s southern terrace. Completed in 1928, the Fine Arts Garden at the Cleveland Museum of Art still contains much of the original Olmsted design.

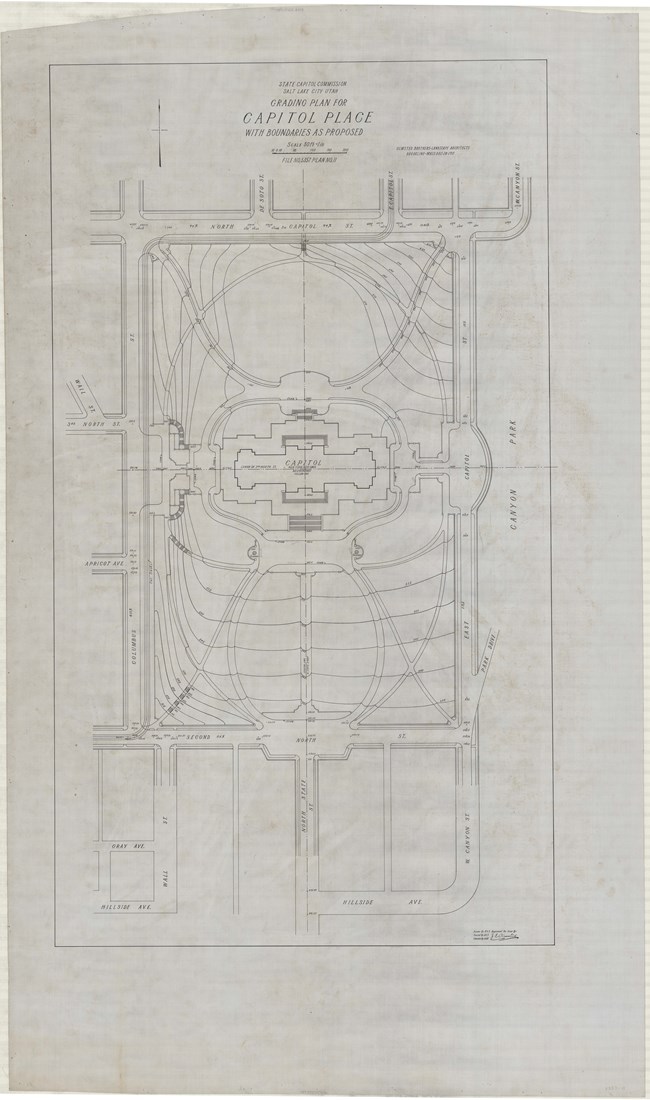

Olmsted Archives Utah State Capitol (Salt Lake City, UT)In 1911, after acquiring appropriations from Utah State Legislature and securing a topographical map, Olmsted Brothers were employed to provide a preliminary site plan for the Utah State Capitol. John Charles Olmsted took the lead, spending nine days in Salt Lake City sketching ideas, and examining soil and elevations.Olmsted found the views favorable and suggested implementing terraces to situate the building at the highest point possible. He recommended grading slopes lower to allow views up to the building from all sides, and carefully planted trees to avoid any obstruction of views. Olmsted’s plan, classical in nature, included an oval pathway that would intersect other curved paths. He called for Utah State Legislature to buy up and remove all houses on Capitol Hill, which was likely unpopular at the time since Utah’s most influential citizens were living on Capitol Hill. The location of the Utah State Capitol was eventually shifted two hundred feet to the south to provide space for future buildings. This change would complicate Olmsted’s grading plans, which he asked to revise, but was denied. Despite other public buildings being added, the preeminence of the Utah State Capitol and the view from all sides conveys much of Olmsted’s design intent.

Olmsted Archives Robbins Memorial Town Hall (Arlington, MA)Moving from the late 19th to early 20th centuries, one of the wealthy families of the area, the Robbins’, gave their time and wealth to the betterment of the town. The Robbins family funded and built Arlington’s main library, town hall, as well as gifting their mansion to the town. The two surviving sisters, Ida and Caira, oversaw the construction of both the Town Hall and associated gardens.In 1938, the Robbins sisters hired Olmsted Brothers to redesign the gardens by Town Hall. Firm members James Frederick Dawson and Leon Zach were the main points of contact for this design. The new design transformed the garden into a secluded, welcoming space that included a circular brick walk through the garden and an “informal, woodsy and rocky environment and a naturalistic planting as a background”. Nestled between the Library and Town Hall, the gardens provided a quiet respite for visitors and citizens, something they continue to offer today. Olmsted Brothers’ work would continue till 1941, working to keep many of the key water features intact.

Olmsted Archives Washington State Capitol (Olympia, WA)On April 13th, 1911, John Charles Olmsted, without any contract in place, made Olmsted Brothers’ first visit to the Capitol Grounds in Olympia, Washington for a meeting with the State’s Governor and Capitol Commission, for a tour of the grounds. That same year, Olmsted Brothers would create a master plan and architectural drawings for the 54-acre site.The plan had a complex of six buildings on the lawn, with the classical Legislative Building as the centerpiece. Olmsted Brothers suggested a naturalistic treatment of the site with plantings of low, well-pruned trees along the edge of the site, blocking the view of industrial buildings but leaving the mountain vista on the opposite side open. Throughout the project, Olmsted Brothers stressed the importance of establishing a connection between the Capitol Grounds and downtown Olympia. The firm recommended a diagonal avenue along the edge of the Capitol Campus going down to Sylvester Park. Twenty years after it began, Olmsted Brothers’ work on the Capitol Campus was complete.

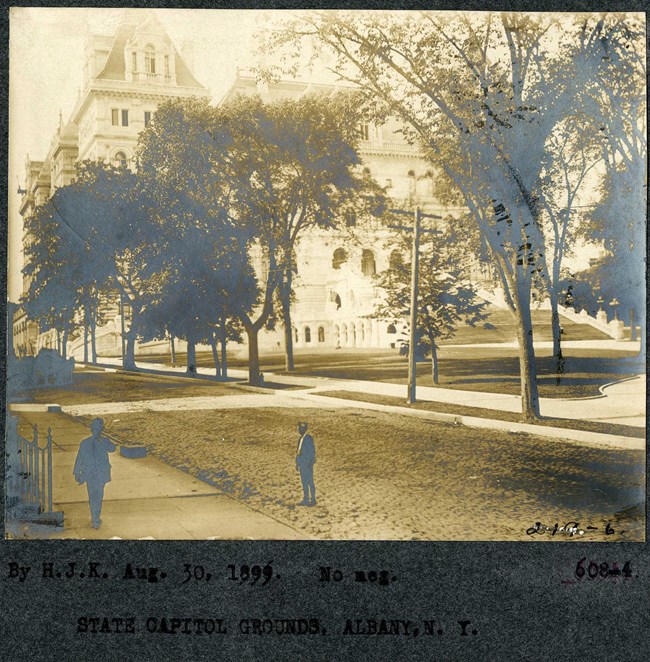

Olmsted Archives New York State Capitol (Albany, NY)In 1867, construction on the New York State Capitol in Albany began, though Frederick Law Olmsted wasn’t asked to join the project till 1874. While Olmsted was asked to advise on the Capitol’s expansion and improvement, several disagreements occurred between Olmsted and the State Officials on the architectural style of the ground floor, as well as Olmsted’s additions.The 1876 Report of the Advisory Board declared that “the Capitol should be an architectural monument worthy of the grandeur of the Empire state.” At this point, the Advisory Board took over design control from Olmsted, suggesting a balcony and both inner and outer staircases should be included to add to the building’s status. All further design choices were made to add interest and beauty to the Capitol’s exterior.

Olmsted Archives State House (Hartford, CT)In 1893, John Charles Olmsted was invited to his father’s home state of Connecticut to advise on improvements to the State’s Capitol Grounds, with a particular focus on Trinity Street, drives and terrace alignments, plantings to screen the nearby railroad, and various monuments. John Charles never got a true chance to work on what he called the State House due to his death in 1920, at which point firm members Edward Whiting and James Dawson became involved.Between 1925 and 1932, Whiting and Dawson’s planning efforts included rearranging surrounding roads and bridges to increase accessibility to the State House. Work picked up again in 1939, with Whiting and Olmsted Brothers firm member William Marquis. Up until 1947, the pair were developing new entrance plazas and terraces for the State House, as well as relocating sculptures and memorials, and improving the connection between the State House and nearby Bushnell Park.

Olmsted Archives Malden Library (Malden, MA)In 1884, Henry Hobson Richardson and Frederick Law Olmsted traveled to Malden, Massachusetts to choose a site for the city’s new Public Library, known as the Converse Memorial Library. Richardson employed his popular classic sandstone façade, as he had done on many public buildings. For the landscape, Olmsted designed a courtyard for the L-shaped library, allowing visitors a space to gather. Olmsted also created a separation between the green entrance lawn and an open court by employing a short wall and wrought iron gate.

Olmsted Archives Memorial Hall (North Easton, MA)Another collaboration between Frederick Law Olmsted and Henry Hobson Richardson, North Easton, Massachusetts’ Memorial Hall combines Richardson’s Romanesque architecture with Olmsted’s natural landscape design. Olmsted was hired in 1887 by the Ames family, local business owners and early investors in the Union Pacific Railroad.With a sloping topography, Olmsted chose to integrate the grounds of the hall with the neighboring library, which forced him to remove fencing, extend the front of the lawn, and add additional shrubbery. In his preliminary report, Olmsted also proposed reorienting the entrance, and building a stone wall along the edge of the property. In 1903, Olmsted Brothers got a chance to add to Memorial Hall, preparing an updated planting plan for the property.

Olmsted Archives Crane Library (Quincy, MA)Built in 1881 by architect Henry Hobson Richardson and landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, the Crane Library was one of several collaborations between the pair. Olmsted’s first task was re-grading the site, making it level with the street to create a flat canvas for the construction of the library. As the landscape architect, it was Olmsted’s job to showcase the red and stone façade of the building, so the planting plan for Crane Library included an open green turf, with scattered shrubbery along the grounds.An 1883 edition of Harper’s Weekly called the Crane Library, “the best Village library in the United States,”. Olmsted Brothers would get a chance to add to the library grounds when the City of Quincy reached out in 1913, asking them to advise on “the adjustment of the library grounds to the proposed widening”.

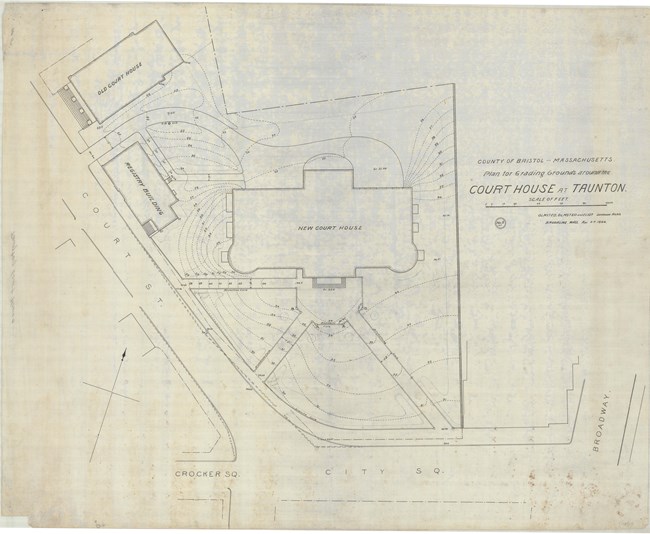

Olmsted Archives Bristol County Court House (Taunton, MA)When Taunton, Massachusetts was planning a new courthouse for their city, Taunton-born architect Frank Irving Cooper was the first man to be hired. On behalf of the County Board of Commissioners, Cooper began corresponding with Olmsted Brothers, hoping to hire them to design the grounds around the courthouse.Olmsted Brothers would correspond with Cooper for several years about landscaping plans for what would be known as the Bristol County Superior Courthouse. On January 31st, 1894, Olmsted Brothers wrote to Cooper stating that they would be making a preliminary visit to the site, to better work out a plan as well as determine what their fees would be. By March, John Charles Olmsted had made his visit to Taunton, and they began planning. In June they informed Cooper that planting of the grounds would begin that Fall. By November of that year, Taunton Commissioners had made changes to the Olmsted plan, including hiring their own nursery for the plants. Olmsted Brothers were not made aware of this change until Cooper wrote to inform them. On November 24th, Olmsted Brothers wrote to Cooper stating “If you will send us a copy of the contract and specifications as signed by the Commissioners and the nursery company, we will, if the Commissioners desire it, visit the ground in order to see whether, in our opinion, the contractor is living up to the contract. If we are not asked to do so, we do not see that we are in any way connected with the work now going on,”. Planting at Bristol County Superior Courthouse followed Olmsted Brothers plans, and the Olmsted’s formed a close bond with Cooper, even helping landscape Cooper’s own property the following year.

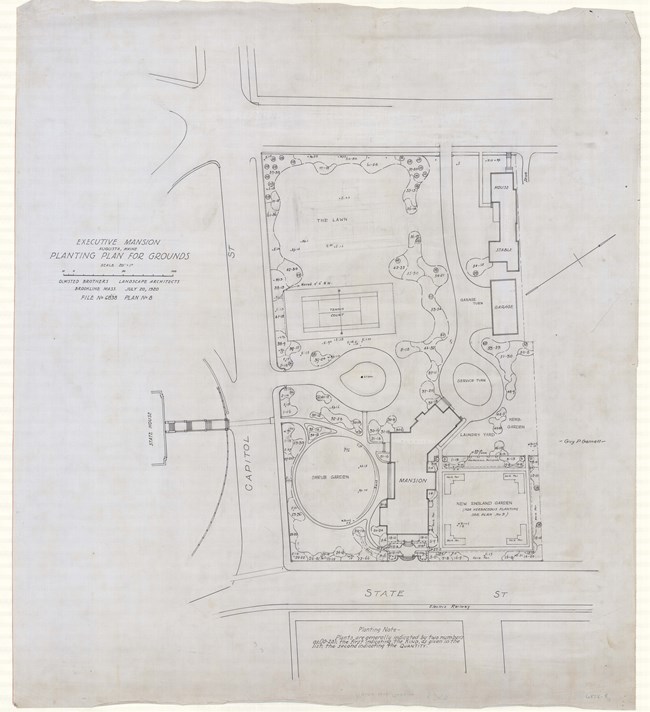

Olmsted Archives Maine Governor's Mansion (Augusta, ME)In 1920, Maine’s Governor Carl E. Miliken commissioned Olmsted Brothers to design the grounds of the Governor’s Mansion. Firm member Carl Rust Parker took lead on the design, preparing plans not only for the mansion grounds, but also the State House and Capitol Park. Work on the mansion continued sporadically until 1929.Parker proposed a formal entrance, service area, and shrub garden paired with a New England Garden, as well as a central lawn surrounded by paths and fencing. Due to limited funding, only planting areas and fencing were installed. In 1984, a landscape rehabilitation project led to the construction of Parker’s formal entrance. Years later in 2016, Parker’s original design for the front facing grounds were restored.

Olmsted Archives Maine State Capitol Grounds (Augusta, ME)In 1920, the year Maine celebrated its 100th anniversary of separating from Massachusetts, then Governor Carl Milliken commissioned Olmsted Brothers to prepare plans for improving and uniting the Governor’s Mansion, State House, and Capitol Park. Carl Rust Parker took lead on all three designs, and at the State House, he proposed relatively minor landscape improvements, wanting the natural characteristics of the scenery to dominate.Parker left the Bulfinch terraces intact, revised the planting plan, relocated drive, and suggested new paths to State Street. Due to limited funding, only parts of his plan were implemented.

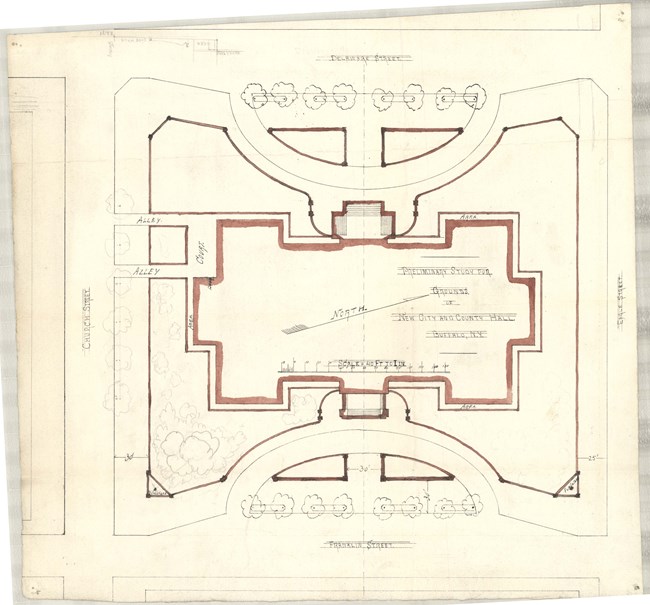

Olmsted Archives Buffalo City Hall (Buffalo, NY)After Buffalo, New York’s County and City Hall were completed in 1875, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired to prepare a Preliminary Study for the grounds of both buildings, including sketches for proposed tree and shrub plantings. By 1931 a new City Hall was built, and the grounds Olmsted designed now serve the Erie County Clerk Offices, which still retains his original design.

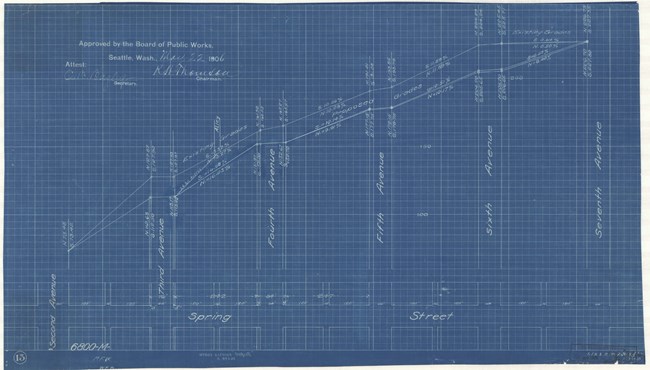

Olmsted Archives Seattle Public Library (Seattle, WA)In 1906, the exact day John Charles Olmsted arrived in Seattle to plan the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, he was called upon to lay out the grounds for Seattle’s new library. The 55,000 square foot Beaux Arts-style building was nearing completion when John Charles arrived to consult, but legal issues between the City and Library delayed work on a solution to resolve the access issues that arose due to street regrading. |

Last updated: June 14, 2024