|

From the beginning of his career, Frederick Law Olmsted had a clear concept of what constituted a “park”, and he devoted much time and energy to explaining the difference between a park and other types of public recreation grounds. The purpose of a park was to provide city dwellers with an experience of extended space that would counteract the enclosure of the city by providing “a sense of enlarged freedom.” An expanse of meadow with gracefully contoured terrain, gently curving paths and an indefinite boundary of trees was the central element of the park. Every city, he was convinced, needed such a freely accessible public space. It would provide the most effective antidote to the debilitating artificiality of the built city and the stress of urban life. The park made possible what he termed “unconscious” recreation, whereby the visitor achieved a musing state, immersed in the charm of naturalistic scenery that acted on the deepest elements of the psyche. There the visitor could experience an “unbending” of the faculties that would restore mental and physical energies, renewing strength for the daily exchange of services that sustained the community of the city. This public space would serve a variety of different activities for groups of visitors, with no group or activity monopolizing any part of it. To achieve this, all design details were rigorously subordinated to promote the psychological effect of the park space, by a means that Olmsted called “the art to conceal art.” Olmsted believed that in a park, in addition to restorative landscape, “the largest provision is required for the human presence.” He planned extensive systems of walks and drives for visitors, and designed sections of his park for the gathering and entertainment of crowds. There were places for civic gatherings, for music concerts and for promenades. There were refectories for providing food and beverages and facilities for children’s play and gymnastics. Through the years, as team sports became more popular, there was a provision for them as well, in separate areas that avoided an “incongruous mixture” of uses and left the landscape experience undisturbed. The separation of interior ways- drives, paths and bridle paths- from each other, and of cross-park city traffic from the park’s circulation systems, also strengthened the landscape experience. A corollary design principle was the provision for active sports and crowd activities in separate spaces at a distance from the principal park of the city. The purpose was to supply a number of all-city uses, not a series of merely local recreation grounds. Such a system of parks and recreation grounds first clearly accomplished in Buffalo, New York, created a structure of green spaces in advance of the concentrated settlement of residential areas. Completing this system were ribbons of public space in the form of parkways that facilitated movement through the city and served as neighborhood outdoor resting places. Usually two hundred feet wide, the parkways separated the commercial traffic of carts and wagons from private carriages and provided separate ways for pedestrians and equestrians. Olmsted also advocated creation of linear greenways along urban stream valleys. The classic example is the valley of the Muddy River between the Charles River and Jamaica Pond in Boston and Brookline, Massachusetts. Olmsted also urged public ownership of areas of special scenic beauty and the creation of scenic reservations where the principal role of the landscape architect was to construct a circulation system that would facilitate enjoyment of the scenery with least intrusion on it. During the twenty-five years between the retirement of Frederick Law Olmsted and the death of John Charles Olmsted, the firm designed extensive park systems for many cities. After the 1920s, the Olmsted firm created few parks of the size created by the earlier firm, and with more emphasis on utilizing urban stream valleys. In its later years, the firm also placed much greater emphasis on local parks that provided active facilities, including the fieldhouse that marked the Progressive Era, and facilities for team sports. In several instances this involved planning areas for recreational athletic fields adjacent to older city parks. The decades of the 1920s and 1930s saw Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. and other firm members carry out extensive and innovative work in country, state and national park planning and scenic preservation. Text taken from The Master List, written by Charles E. Beveridge Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

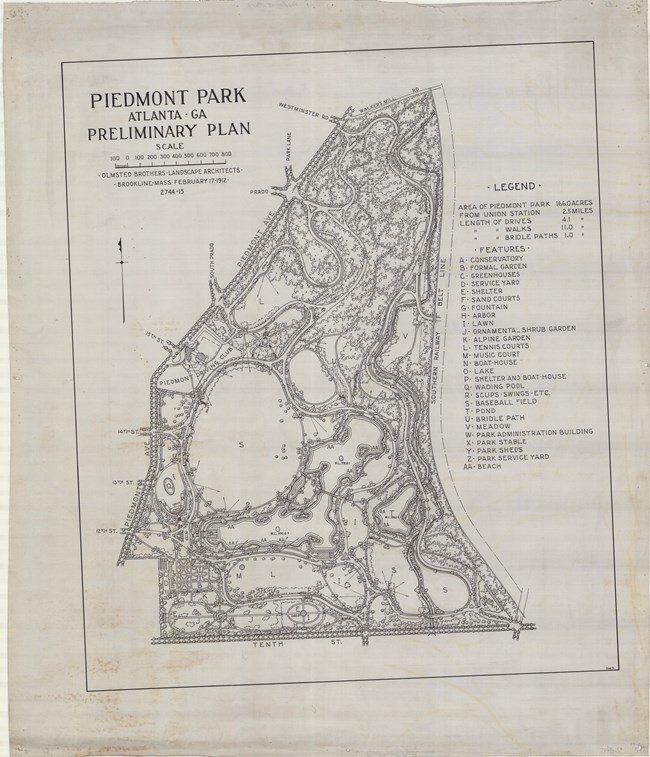

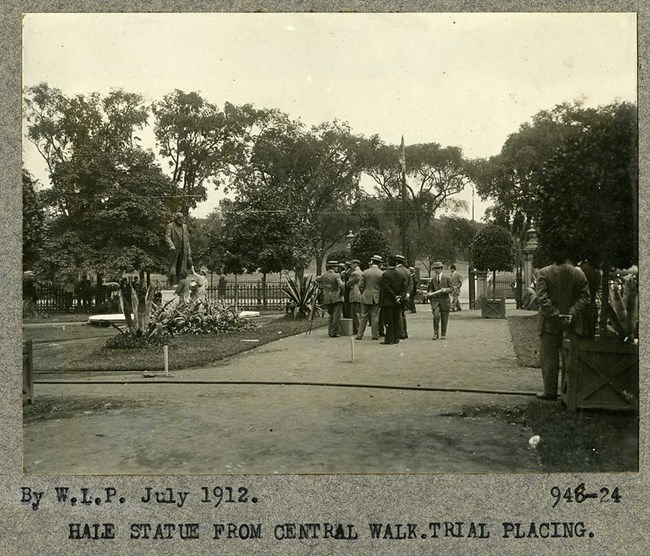

Olmsted Archives Piedmont Park (Atlanta, GA)While Piedmont Park was designed by the Olmsted Brothers, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. was the first in the family to walk across the land the park would eventually become. During the late 1880s and early 1890s, this land was the venue for numerous fairs and expositions. In 1895, the site was chosen for the Cotton States and International Exposition, at which point Olmsted Sr. was consulted on the layout of the exposition, influencing elements of the plan. After the extravagant exposition, Atlanta was unsure of what to do with the 187 acres of forest. The City of Atlanta was hesitant about buying the land, believing the park was too far away from the city. However, in 1904 Atlanta purchased the land that would become Piedmont Park, and even extended its city limits to encompass the park acreage. In 1909, Atlanta elected to transform the decaying fairgrounds into a park. They wanted their own Central Park, though its designer, the Sr. Olmsted, had passed years before. So, Atlanta got the next best thing; they hired the Olmsted Brothers to develop its master plan. The Olmsted Brothers plan would utilize already present stone stairways as access paths between the different levels of the park’s grounds. Despite the City agreeing to pay $1,800 for the plan, Olmsted Brothers were concerned Atlanta may not have enough money to make necessary improvements as they came up. As the Olmsted Brothers worked on Piedmont Park from 1909 to 1912, the design they implemented reflected the picturesque style and design principles they had learned from their father. The Piedmont Park the Olmsted Brothers designed featured broad grassy lawns and playing field, shaded woodland with over 15 miles of walks, drives, and bridal paths. Due to budget constraints, some, but not all, of the Olmsted Brothers’ plan was realized. Nevertheless, the Olmsted Brothers plan greatly influenced the development of Piedmont Park. Much of the landscape and vistas remain today, providing green space for the urbanized neighborhoods surrounding the park. Though the Olmsted Brothers plan wasn’t fully realized, the current master plan for Piedmont Park, adopted in 1995, honors the brothers’ original vision for the park.

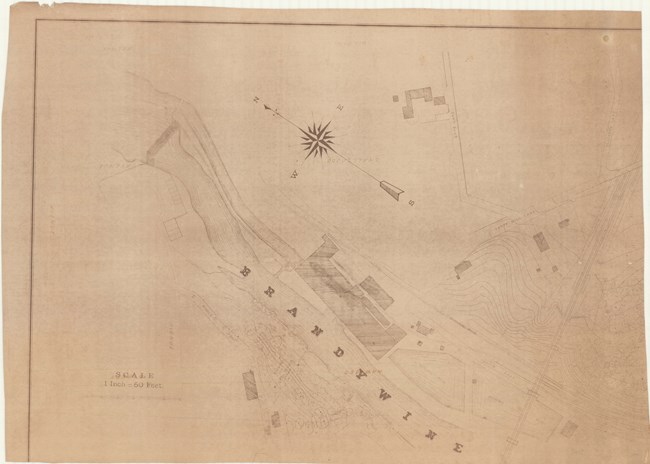

Olmsted Archives Brandywine Park (Wilmington, DE)Frederick Law Olmsted didn’t teach in a classroom or assign homework. Instead he taught his students, future professionals in landscape architecture, about the best practices for achieving an urban park. Though he wouldn’t go on the have a career in landscape architecture, Samuel Canby was one of the many concerned professionals who reached out to Olmsted in the late 1800s, seeking advice on how to better his hometown of Wilmington, DE. Enthusiasm for open green space was growing the United States, thanks in large part to European park planning, where social and economic forces meant creating a better environment for the masses a priority. In 1883, Delaware legislature passed a bill providing "Public Parks for the use of the citizens of Wilmington and vicinity, and creating a Board of Park Commissioners to take the care and management of such lands as would be acquired under the provisions of the act.”. Canby, the first president of the Board of Park Commissioners, was also appointed chief engineer in laying out the new park. Immediately, Canby sought the advice of Olmsted. Olmsted took a trip to Wilmington where he viewed several possible sites for the new park. Upon seeing Brandywine Creek, he enthusiastically recommended the land along the water be obtained for a park. With Olmsted as his teacher, Canby made sure to embrace and enhance the natural beauty of the land. Also, from Olmsted, Canby blended roads, pathways, and walkways to make them inconspicuous within the park landscape. Not only is Brandywine Park the largest urban park in Delaware, it was the first park established in Wilmington, fulfilling the growing city’s need for public recreational space.

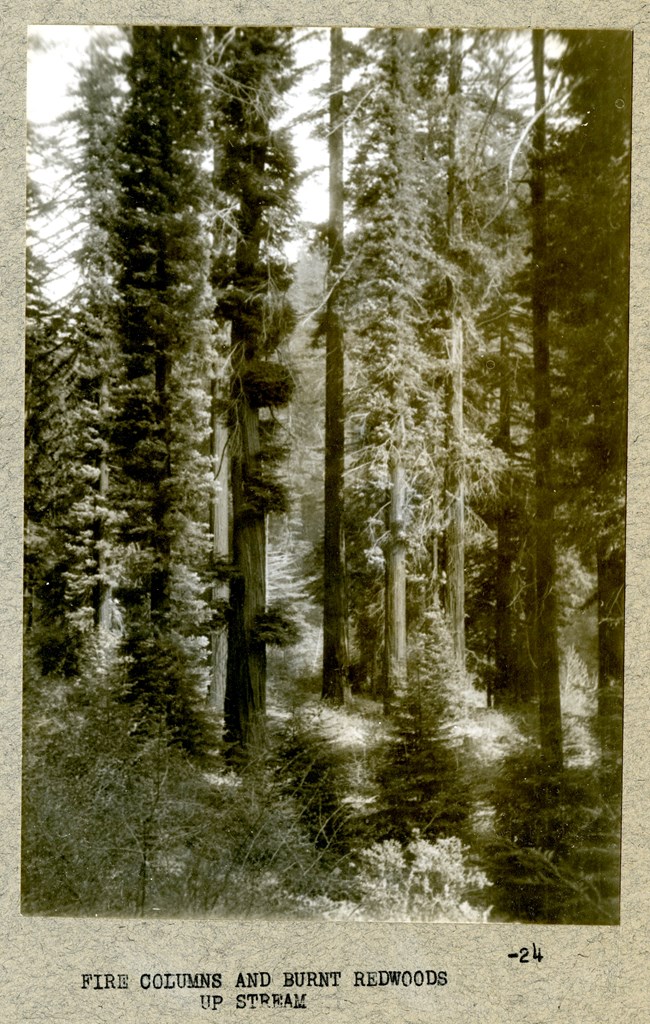

Olmsted Archives Redwood National Park (Crescent City, CA)Though Olmsted Jr and his father both contributed extensively to California State Parks, and the National Park Service in general, today we’ll focus specifically on Jr’s fight to protect California’s natural wonder. In 1917, then NPS director Stephen Mather traveled with a group of conservationists in California to investigate the old growth redwoods that were being logged in vast numbers. Shocked and saddened by the destruction they saw, a year later they established Save the Redwoods League in the hopes of protecting the groves by purchasing the land they sat upon and creating a public park. The League enlisted Olmsted Jr in 1927 to conduct a survey of the area, eventually laying out the long-term goals for the California park system. Being a respected voice in the conservation community, it makes sense the League and California wanted him to shape their vision. Olmsted Jr’s master plan for saving the remaining 5% of California’s Redwoods was a success, and in 1953 Redwood National Park dedicated Olmsted Grove to the man whose contributions to protect our national parks will forever be as powerful as the trees he fought to protect.

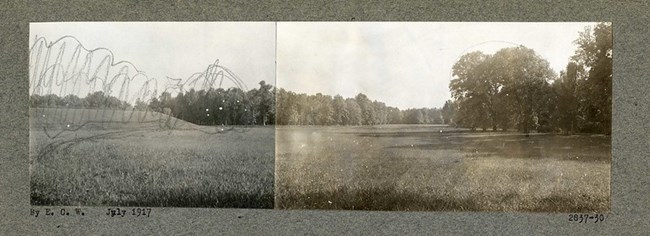

Olmsted Archives Rock Creek Park (Washington, DC)In 1886, Olmsted Sr. warned that “the charmingly wooded glen of Rock Creek [was] in private hands, subject any day to be laid waste”. Throughout his career, Olmsted fought hard to warn anyone who would listen of the dangers that lay in keeping such beautiful land private. It wasn’t until Olmsted Jr. was chosen to be part of the McMillan commission, in charge of developing both the core and park system of Washington, D.C., that Rock Creek Park would get its deserved attention. Once on the commission, Olmsted Jr. encouraged his colleagues to endorse the acquisition of land for new public parks and scenic drives throughout the city, including the preservation of Rock Creek Valley in its entirety. By 1918, Olmsted Jr. and his brother John were busy on the plan for Rock Creek Park. They proposed dividing the landscape into six distinct areas that remain today. The topographical and psychological backbone of the park, their report stated, would be the area along the banks of the creek and its tributaries. This “Valley Section”, as it was described, would be preserved in its natural state, with only the addition of scattered picnic spots. Rock Creek Park’s “woodland” would consist of the western hills and plateaus, contained in the South by Military Road. Olmsted Brothers saw the “woodland” area as a spot for intensive use; their report recommended the installation of hiking paths and numerous picnic groves. Olmsted Brothers even saw an area beyond their “woodland”, designated “wilder woodland”, and it was to be preserved to the highest degree.

Olmsted Archives City Park (New Orleans, LA)By the early 1870’s New Orleans, and the rest of the country, was noticing how successful Central Park was becoming, and it hadn’t even been completed yet! City Officials in New Orleans knew they wanted to hire Frederick Law Olmsted to design a park for their city. Due to many cities having that same thought, Olmsted sent two employees to New Orleans to work on City Park. Two engineers on staff for the Olmsted Firm arrived in Louisiana: John Bogart and Colonel John Yapp Culyer. Bogart had been an engineer on staff at both Central Park and Prospect Park, while Culyer, also an engineer at both Central Park and Prospect Park, also followed Olmsted to D.C. to help form the United States Sanitary Commission. While in New Orleans, Bogart took notes on the sites condition and created a plan for the City to reference. The two engineers received the first half of their fee, but the Park Board refused to pay the rest, believing that their plan was inadequate. Obviously frustrated, Bogart and Culyer sued for the remaining money. Despite loosing in a lower level court, they prevailed and received their compensation after brining it up in Louisiana’s Supreme Court. The lawsuit certainly took some excitement out of citizens and the prospect for a new park. It wouldn’t be till the early 1930’s that the Olmsted name would return to City Park, this time as Olmsted Brothers. Among their work at City Park, Olmsted Brothers focused heavily on designing the area surrounding Popp Fountain, a memorial to local lumber tycoon John Popp. Though the Popp family donated the money to the City of New Orleans, they requested Olmsted Brothers assist in its design, wanting the best for their namesake.

Olmsted Archives Public Garden (Boston, MA)At the Northern terminal of the Emerald Necklace, you will come across two very different landscapes. While the Boston Common is a primarily unobstructed open space, the Boston Public Garden contains a lake, and a series of formal plantings to compliment. The Boston City Council believed “the area of our city is too small to allow the laying out of large tracts of land for Public Parks, and it behooves us to improve the small portions that are left to use for such purposes”. Thankfully, Olmsted’s previous work at the Back Bay Fens gave Boston the expanded space it needed. Though the Boston Public Garden lay stagnant for many years until funding and a design was approved, at which point the salt marsh was established as the first public botanical garden in the United States.

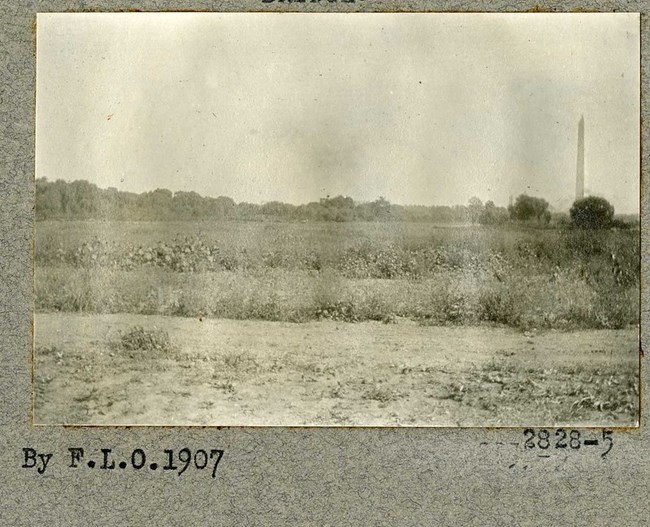

Olmsted Archives The Mall (Washington, D.C.)While his father did some work in the district, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. had an enormous influence over the design of Washington D.C. Starting as a member of the Senate Park (McMillan) Commission in 1901, Jr. founded and served on the Commission of Fine Arts from 1910 to 1918, and was a member of the National Capital Park and Planning Commission from 1926 to 1932. The National Capital Park and Planning Commission was tasked with restoring the National Mall to its original design as Pierre Charles L’Enfant had envisioned it. Olmsted Jr.’s redesign of the National Mall, beginning in the mid-1930s, helped to transform a densely planted Victorian park into formally arranged lawn panels lined with trees. This design would emphasize the importance of the view between the U.S. Capitol Building and the Washington Monument. Olmsted Jr. made radical planting changes during his work on the National Mall, removing nearly every tree and replacing them with rows of American elms, following what was described in the 1901 McMillan Plan. Olmsted’s work of many decades, not just on the National Mall but Washington D.C., helped create a city threaded by parks, creating a unified special composition.

Olmsted Archives Everglades National Park (Homestead, FL)In 1919, the National Parks Association was founded as an independent supporter of the National Park Service, to protect and enhance our park systems for generations to come. The NPA Board of Trustees was filled with prominent American conservationists, including Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. By 1928 the campaign for a park in the Everglades got rolling, with Jr. focusing on the park’s functions and purposes rather than specific prohibitions, as many Florida Representatives wanted. In 1931, William P Wharton joined the fight for a national park in the Everglades. Wharton was involved in the Massachusetts State Park System, National Association of Audubon Societies, and the American Forestry Association, a perfect match to join Olmsted Jr. in crafting the report for a proposed national park in the Everglades. Olmsted Jr. and Wharton would spend ten days walking extensively in the Everglades region, speaking with fisherman, guides, hunters, and trappers. After their adventure, the two concluded the Everglades not only had all the qualities necessary for a national park but was also so different from any other in existence, having a “special force of novelty”. Olmsted Jr. and Wharton believed that coastal mangrove forests and “the abundance of many species of wild bird life not commonly found in other parts” made the Everglades highly desirable for a national park. Despite not proposing any specific recommendations for park development, they firmly believed believing “that the primitive character of the region should be protected to the utmost.” Not only did they see the Everglades as providing recreational enjoyment, they also saw the importance it would serve as a study site for botanists, zoologists, and geologists.

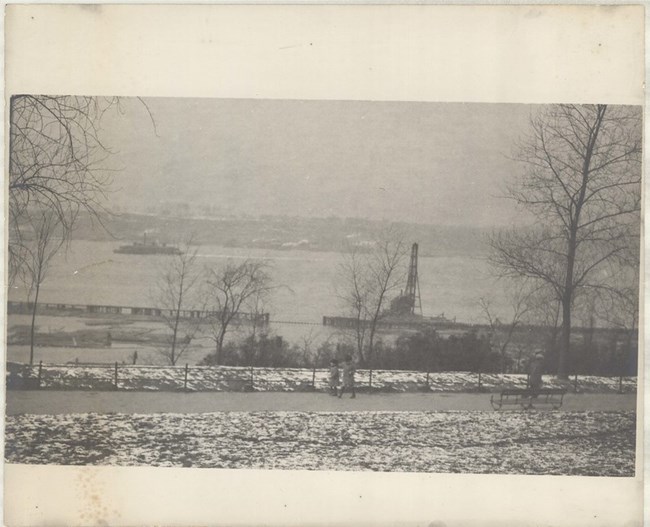

Olmsted Archives Riverside Park (New York City, NY)During his time working on New York City parks, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. clashed several times with Andrew Haskell Green, who often wouldn’t give in to Olmsted’s requests for more money. Despite this, Green does deserve credit for often introducing the bill to legislature in support of a park. In 1866, that’s exactly what Green did, and in 1872, the original 191 acres was acquired as the first segment of what would become Riverside Park. That same year, Olmsted Sr. began preparing a conceptual plan for the new park and accompanying road. After 2 years of gathering information, Olmsted Sr. submitted his report, proposing a combined park and parkway adhering to the curves of the landscape. In his report, Olmsted Sr. wrote that Riverside Park “presented great advantages as a park because the river bank had been for a century occupied as the lawns and ornamental gardens in front of the country seats along its banks. Its foliage was fine, and its views magnificent”. Alongside that river Olmsted Sr. planned Riverside Drive, a treelined roadway winding through the rocky landscape. Though Olmsted Sr. would be out as the park superintendent a few years into construction, his vision lived on in those chosen to take on his work, Calvert Vaux and Samuel Parsons, both of whom had worked closely with Olmsted Sr.

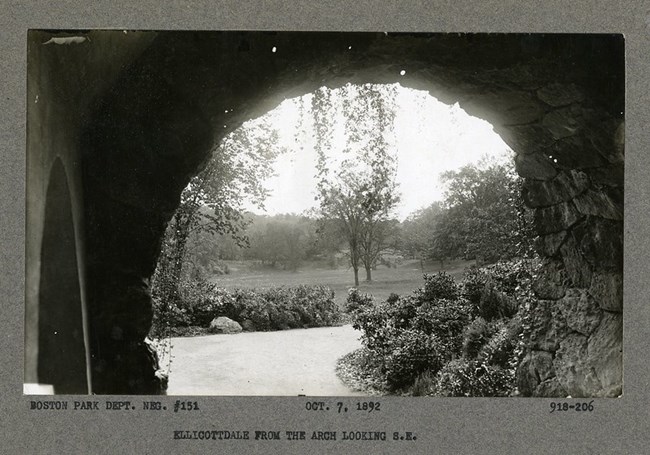

Olmsted Archives Franklin Park (Boston, MA)Before there was Franklin Park Zoo, there was Franklin Park, and before that, just an idea. In 1869, after hearing about the success of other large urban parks, Bostonians requested that the city create a park system. Threatening a growing Boston was the lack of fresh air and increasing death rates, similar threats which had descended upon New York City before Frederick Law Olmsted arrived. Of all the pieces in the Emerald Necklace, Franklin Park is the largest at 527 acres. Olmsted and his son John Charles began the plans for Franklin Park in 1885, though John stayed on supervising construction until 1896. Franklin Park was divided into two sections, with nearly two thirds of the land’s acreage going towards the Country Park, a place for those to quietly enjoy the natural scenery. The second section, the Ante Park, was set aside for active recreation. The Ante Park itself was split into the Playstead, a play area for children, and the Greeting, which was once a promenade and is now part of Franklin Park Zoo. The twenty-year construction process was classically Olmsted in two ways. The first was using existing topography, ledges, native stone, and vegetation to create a picturesque character for the park. The second was that, despite Olmsted meticulously choosing the plantings in the Country Park, those plantings were removed in favor of those that needed less maintenance. While Olmsted didn’t necessarily believe in zoos, he did believe that animals could enhance landscapes in the proper setting. However, after his death the City of Boston hired a former member of the Olmsted firm, Arthur Shurcliff, to design Franklin Park Zoo. On October 3rd, 1912, 10,000 people crammed to see the new bear dens, the first official exhibit of the zoo. By 1920 more than two million people had visited Franklin Park Zoo, but in 1970, Zoo officials found new homes for the bears and closed the bear dens for good. It was found to be too difficult a task to take down the bear proof cages, so they remain in the woods abandoned.

Olmsted Archives Presque Isle Park (Marquette, MI)Peter White, an original settler of Marquette, understood the city was growing and believed it needed a park. In 1857, Michigan State Legislature was due to distribute lands granted to them by the United States, one of those pieces of land being a lighthouse reservation. White wanted that land so badly, he ran for a seat in the House of Representatives and won. White only served one term, though he spent the rest of his life advocating for Marquette. For 29 years the land stayed reserved for light houses (2 still remain to this day), but as the Park Commissioner for Marquette, he personally lobbied Congress to give the land to his city in 1886, finally getting the park he had worked so hard for. In 1891 Frederick Law Olmsted to make his way to Marquette. He was in the Midwest, working on the Chicago Worlds Fair, when he came to the tiny town surrounded by Michigan wilderness. After doing some sightseeing, he was asked to draw up a management plan suggesting how the land could be turned into a proper park. Olmsted, always the environmentalist, wrote Marquette an impassioned letter on what to do with the land. “It should not be marred by the intrusion of artificial objects… Preserve it, treasure it, as little altered as may be for all time… We beg to congratulate Marquette on having one of the most beautiful parks in the world, and to earnestly advise that its natural beauty be religiously preserved at whatever inconvenience, as it will be worth far more than everything that art and wealth can create in a park.” -Frederick Law Olmsted 1891, in his letter of recommendation to Marquette on Presque Isle Olmsted’s letter was taken as gospel by Marquette, and Presque Isle maintained its midwestern wilderness for years to come.

Olmsted Archives Jackson Park (Chicago, IL)Before the idea of a World’s Fair came to Chicago, State legislature first passed a bill calling for the creation of a system of parks and parkways spreading across the whole city of Chicago. The year is 1869, the Civil War has been over for four years, and Chicago’s South Park Commission has just been established to oversee the development of the city’s green spaces. Immediately, Central Park’s great duo of Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux are contacted. Chicagoans were already familiar with the pairs work, since they had designed Riverside village. Olmsted always made sure his designs incorporated natural features of the site, and Jackson Park was no different. Water was meant to be the unifying feature of Chicago’s parks, and was a big reason why Olmsted chose Jackson Park as the site of the World’s Fair: the view of Lake Michigan. When writing about where both the park and fair should be, Olmsted said “There is but one object of scenery near Chicago of special grandeur or sublimity, and that, the lake, can be made by artificial means no more grand or sublime. The lake, may, indeed, be accepted as fully compensating for the absence of sublime or picturesque elevations of land” Olmsted was able to begin designing the inland portion of the park before The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 hit, which put all developments on hold as Chicago worked to rebuild itself. Construction on Jackson Park wouldn’t begin again until 1890, at which point Olmsted began splitting his time between Chicago, and the Biltmore in North Carolina. Before Olmsted arrived in Chicago, the site of Jackson Park was a marshy, uninviting, wind-swept dune. However, out of this environment Olmsted was able create a series of basins and lagoons along the shore, protecting visitors and creating a more peaceful environment. Olmsted’s objective in the environment he created was to elicit the intense emotion that nature and beauty cause.

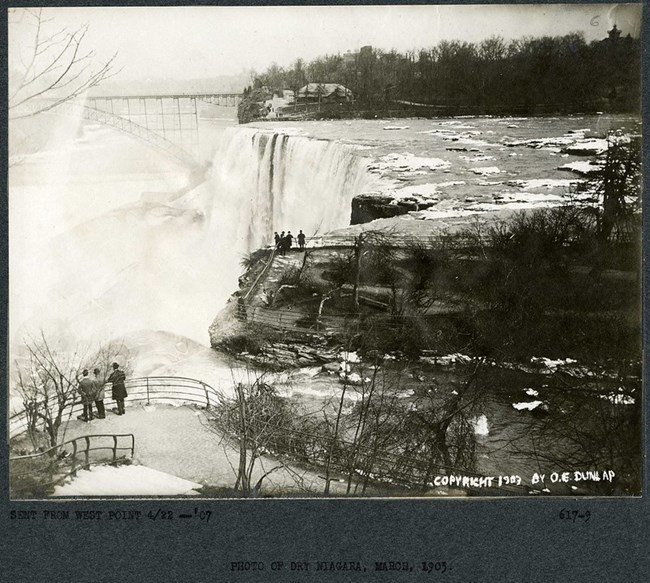

Olmsted Archives Niagara Falls (Niagara Falls, NY)Though Frederick Law Olmsted surely didn’t loose it when he first saw Niagara Falls, he was shocked by the landscape, upon which were “mills and factories everywhere, hovels, fences and patent medicine signs”. The Industrial Revolution of the early 19th century had taken the natural beauty of Niagara Falls and abused it, with buildings going up along the river to harness its power. Olmsted took his first trip to Niagara Falls in August 1869, while working on the Buffalo parks and parkway system. He was accompanied by William Dorsheimer, the district attorney for northern New York and the man who headed the Buffalo parkways commission as well as H.H. Richardson, a friend of Olmsted’s who was working on Dorsheimer’s estate. All three men were appalled with this marvelous view of nature being obscured. In the late 1860s, a small band of early environmentalists who were concerned over the river’s decreasing flow, founded the Free Niagara movement. Intellectuals like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Charles Darwin joined Olmsted in the Free Niagara movement. The movement believed that the natural beauty of the land surrounding Niagara Falls should be protected from commercial exploitations and remain free to the public. The breakthrough at Niagara Falls came in 1883 when Dorsheimer’s close friend, Grover Cleveland, became governor of New York, and signed a bill calling for the establishment of a state park at Niagara. The Niagara Appropriations Bill was signed into law in 1885, creating the Niagara Reservation. Park commissioners first began by clearing out structures that had blocked views along the upper rapids, limiting the number of factories in the areas downstream, Olmsted and Vaux began the landscaping that gives the American side of Niagara Falls its distinct character— ambling walkways and idyllic glades for visitors to contemplate the beauty of nature. Though the view looking into Canada has changed over time, if you’re willing to work for it, you can find certain spots where you’d see the same view Olmsted first did.

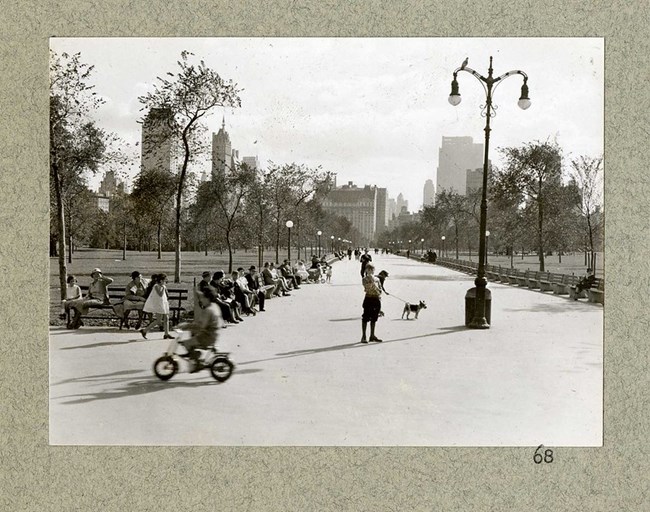

Olmsted Archives Central Park (New York City, NY)Like many city dwellers in the 19th century, New Yorkers only chance for fresh air and pastures were graveyards. Thankfully the city had begun acquiring land, about 843 acres of it, removed from the built-up areas of New York, and in 1853, New York State Legislature approved the establishment of Central Park. In 1857 the Central Park Commission was founded, and Olmsted was encouraged to apply for the position of superintendent of the park, which he was appointed to that same year. To address the rapidly expanding city, the Commission held a design competition for the park. Olmsted teamed up with Calvert Vaux, who he would rely on heavily to the sketch plan. Of the 33 submissions being considered, Olmsted and Vaux’s Greensward plan won over the Commission for its notable combination of formal and natural settings, mixed with architectural details like bridges. The most revolutionary of their design elements was the transverse roads, allowing vehicular traffic and pedestrians to cut through the park simultaneously, without anything detracting from their park experience. After the Greensward Plan was adopted, Olmsted was appointed Chief Architect of Central Park, which he served from 1858 to 1861, allowing him to supervise construction. Unfortunately, from the start, there was a lot of political infighting at Central Park, with Tammany Hall politicians wanting their voters and friends to get jobs at the park, instead of those qualified. There was also Andrew Green, leader of the Commission, whom Olmsted butted heads with over Green keeping the purse strings tight. Central Park was Olmsted’s first great project as a landscape architect, though it certainly wouldn’t be his last, but with every new park or estate you see bits of Central Park in it, for it’s where Olmsted got many of his trademark designs. Besides inspiring Olmsted, Central Park would go on to influence the development of urban parks nationwide, as well as serve as the set for many films.

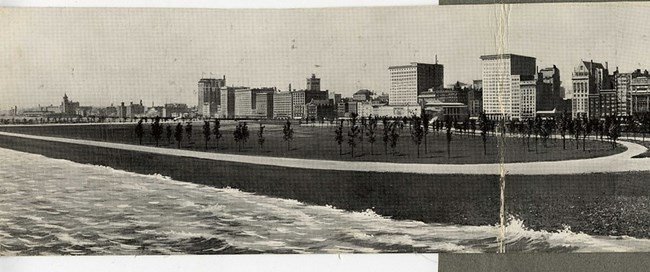

Olmsted Archives Grant Park (Chicago, IL)The Olmsted name has some serious weight in the city of Chicago; Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. planned numerous parks to compliment the World’s Columbian Exposition, which he worked on with Daniel Burnham. Though Olmsted Sr. would pass away, Burnham still had ideas for parks that would need the famous Olmsted touch. Burnham had been working on a park, then known as Lake Park, since the mid-1890s. The city was in possession of the land, however after seeing the success of the South Park Commission at the World’s Columbian Exposition, the city transferred the land to them. After the transfer, the commission changed the name of the proposed park from Lake to Grant, honoring former president Ulysses S. Grant. In 1903, the South Park Commission hired the Olmsted Brothers to assist Burnham. By 1907, the Olmsted Brothers had developed an entirely new plan, calling for a more formalized park structure based off French landscaping principles. This would include symmetrical spaces, along with well-defined paths and plantings. There was a debate over what the centerpiece of Grant Park should be. Burnham had already been chosen as the architect for a new natural history museum, thanks to a $1 million donation from department store owner Marshall Field, and he felt the museum would be a perfect centerpiece. Though Field wanted the museum in the Sr. Olmsted’s Jackson Park, the younger Olmsted sons agreed with Burnham, and the Field Museum was forever placed in Grant Park.

Olmsted Archives Prospect Park (New York City, NY)Frederick Law Olmsted already had his tour of English parks when Calvert Vaux convinced him to rejoin the partnership and submit a plan for the development of Prospect Park. In the 1860’s Brooklyn was its own city, the third largest in the country, and was jealous of the success Central Park was having. James S.T. Stranahan, a successful civic leader in Brooklyn led the effort in the creation of a park. Stranahan argued that Brooklyn “would become a favorite resort for all classes of our community, enabling thousands to enjoy pure air, with healthful exercise, at all seasons of the year.” Stranahan received the first park design from Egbert L. Viele, the man who had proposed the first layout for Central Park before Olmsted and Vaux’s Greensward was chosen. Stranahan asked Vaux to sketch a layout for the park, who then reached out to Olmsted, finishing up his work with the United States Sanitary Commission. Construction at Prospect Park began July 1st, 1866, with Stranahan serving as President of the Prospect Park Commission. Where in Central Park Olmsted and Vaux had to overcome the lands narrow shape and large reservoir at the center, in Prospect Park the two took full advantage of natural elements, such as old-growth forests. As the years went by, Olmsted’s desire to keep statues out of Prospect Park was forgotten, and the park now boats dozens, including one of James S.T. Stranahan. In fact, of the many statues across our country of Abraham Lincoln, the first resided, and still does, in Prospect Park.

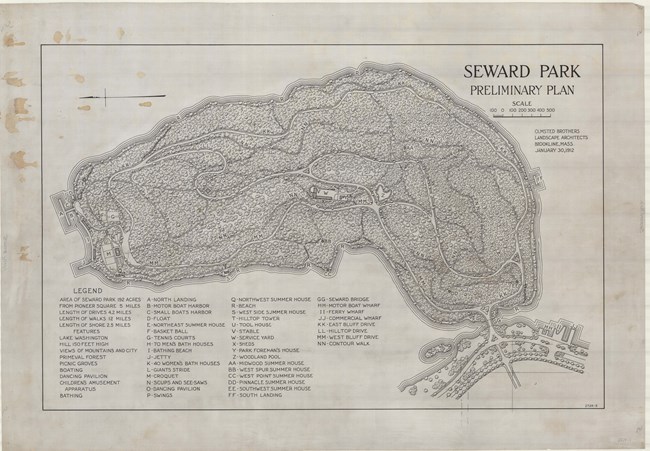

Olmsted Archives Seward Park (Seattle, WA)The Olmsted firm, then Olmsted Brothers after the death of Frederick Sr., were commissioned by the City of Seattle to prepare a comprehensive system of parks and boulevards. Leading the project was John Charles Olmsted, whose first recommendation was to purchase Bailey Peninsula, then outside city lines. In his 1903 report, John Charles encouraged Seattle to acquire the land before the forest was cleared for logging or development. The city began purchasing and developing land according to Olmsted’s suggestions, and in 1911, Seattle finally purchased the Bailey Peninsula for $322,000. As the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition neared, Seattle pushed hard to develop the parks and boulevards John Charles had previously recommended in 1903. Bailey Peninsula became Seward Park to honor former President Lincoln’s Secretary of State, William Seward, who was responsible for purchasing Alaska from Russia in 1867. John Charles Olmsted wrote his preliminary plan for Seward Park in 1912, where he called for programmed spaces like a dancing pavilion, tennis and basketball courts, and a small boat harbor. The design is a perfect example of the Olmsted Brothers’ ecological approach to designing parks, with many woodland and shoreline trails. Though the Olmsted plan was never fully implemented, John Charles’ 1912 plan influenced later development at the park, and one of Seattle’s oldest growing native forest, the same that John Charles marveled at, got to retain its habitat

Olmsted Archives Yosemite National Park (California)Frederick Law Olmsted didn’t arrive at Yosemite for a vacation but was here to work; he took over as the general manager for the Mariposa gold-mining estate. Many thought he was crazy to leave behind his landscape architecture work, and his father made sure Frederick knew his displeasure over the move. However, at the time no one could have known that this move would set the stage for the creation of parks from the natural domain. A year after his move to California, the state had secured a grant deeming Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove inalienable parkland. A commission was formed to oversee the creation of the public preserve, with Olmsted serving as Superintendent and Chairman. Another year would pass before Olmsted wrote his report on Yosemite Valley and Mariposa, stressing the uniqueness of the valley, not because of the towering cliffs, but because of the union of the entire landscape, and the experience of taking it all in, uninterrupted. Olmsted wrote his report for Yosemite and Mariposa with a distinct eye for the times; the Civil War was over and he was expanding upon Lincoln’s vision for a broader, more inclusive interpretation of democracy as he wrote the foundation for our national park system. Like father, like son, Olmsted Jr. would join in on his father’s fight 50 years later when asked to refine his father’s work and address the need for a new bureau to manage scattered parks and monuments. This would start a 6-year correspondence, culminating in Jr.’s writing of the Organic Act, which would help solidify the creation of the NPS, keeping great natural wonders in the hands of the people.

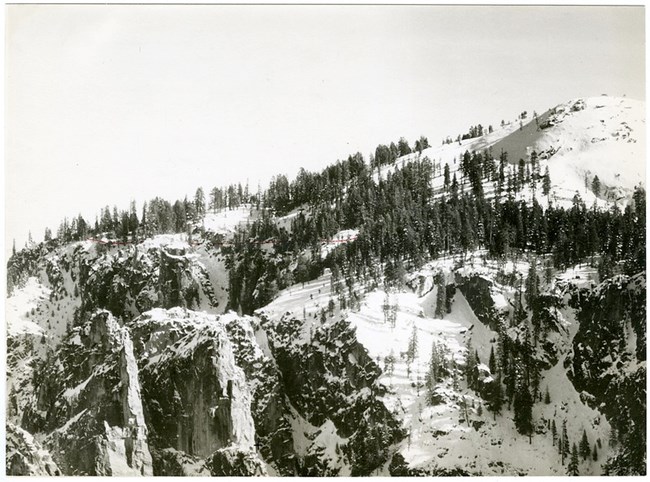

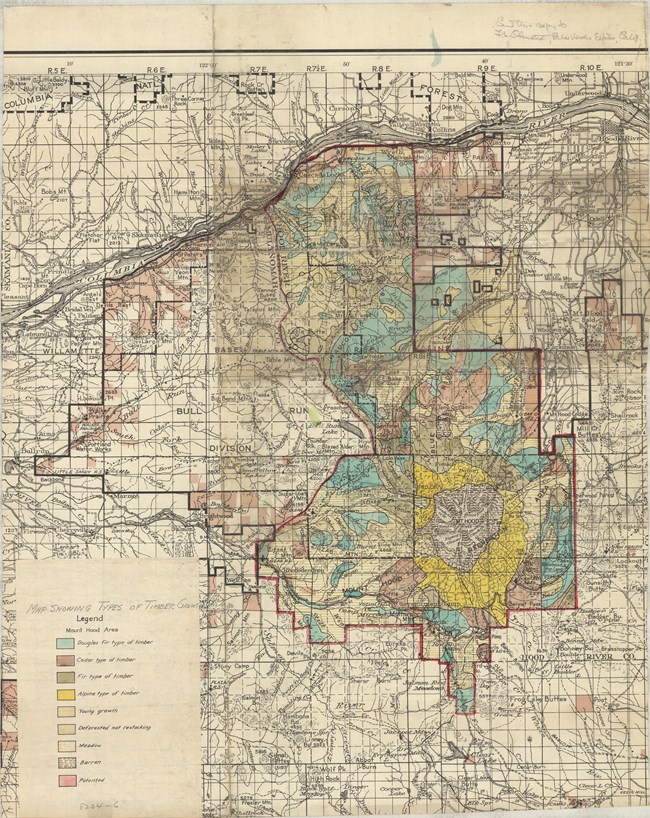

Olmsted Archives Mount Hood National Forest (OR)Intrusion at Mount Hood began in 1926, when a nearby development corporation applied for a permit to construct a cable railway from an Inn deep in the woods to the summit of Mount Hood. After their first application was denied, a letter writing campaign began, stressing that the cable would provide access to the summit for a broader range of people; those who didn’t have the inclination or ability to reach the summit but deserved the opportunity regardless. However, groups of climbers fought back, arguing that rewards like reaching a should be reserved for those willing and able to get there on their own. Unsure of how to handle the situation, then Secretary of Agriculture William Jardine brought together a team of objective experts to evaluate the situation, and on that team was Olmsted Jr. In 1930, Olmsted stated that developments like the cableway would be "insistent visible reminders that in reaching the vicinity of timber line one had not escaped for a time beyond the sophisticated and man-dominated region of everyday life.” The proposal for putting the cable railway in Mount Hood was rejected, and Jr. hoped this victory would serve as a precedent: sacrificing immediate popular ideas for what’s best for the entire area. Jr. and his team also advised against private summer homes around the lake, instead recommending camp houses available to the public. Sr. led the way in advocating an appreciation of parks, going beyond the spectacular scenery they offer. Jr. continued that advocacy work, realizing Mount Hood would achieve far greater fame and value if it was able to keep development off its land.

Olmsted Archives King's Beach (Swampscott, MA)In 1888, the Swampscott Land Trust purchased 130 acres of the Mudge Estate, the summer home of a wealthy Boston family. The Trust commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted to plan the North Shore’s first residential subdivisions. Olmsted’s vision, like in many of his designs, was to encourage the full utilization of the area’s natural topography, which he did by creating curvilinear roads to go around the landscape. As always, he didn’t want decorative elements to take precedence, and made sure to harmonize the man-made structures with the picturesque landscape. For New Englanders in the late 19th century, Swampscott, an esteemed seaside resort community, was the perfect place to spend summers. From all over New England peopled flocked to Swampscott for the town’s fresh ocean air, picturesque scenery, and warm hospitality. In 1895, the Olmsted firm was contracted to begin improvements on King’s Beach. Despite the hundred plus years since work on the beach and residential neighborhood commenced, the area is exceptionally well preserved. So, the beach you see behind Jennifer Lawrence is exactly the way the Olmsted firm left it, with the addition of a few buildings.

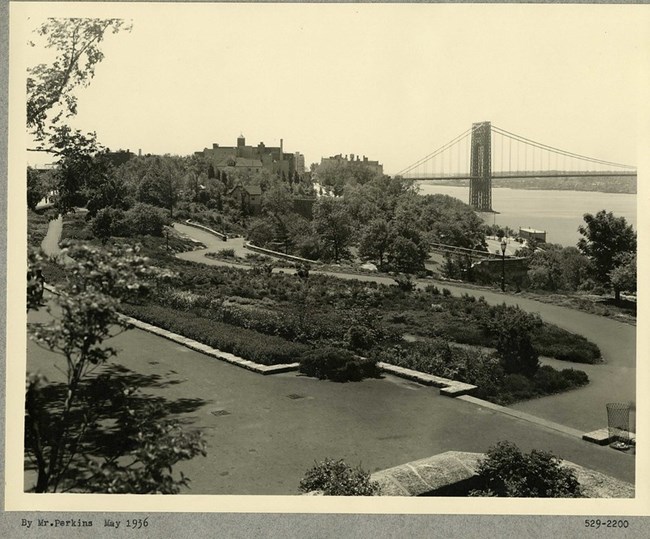

Olmsted Archives Fort Tryon Park (New York City, NY)Before being known as Fort Tryon, the area known as Mount Washington served as a battle site along the Hudson River during the Revolutionary War. British troops stationed there had named the site after William Tryon, the last British governor of colonial New York City. After the Americans won the war, they re-appropriated the name and referred to the area as Fort Tryon. In 1917 John D. Rockefeller had purchased much of the land Fort Tryon sat on, with the vision to develop it into a park. Ten years later Rockefeller Jr. contacted Olmsted Brothers to develop that park, with Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. taking a particular interest in the project. Jr. spent four years transforming Fort Tryon’s rocky soil and topography into a manicured landscape. He designed Fort Tryon Park with promenades, terraced, wooded slopes and eight miles of paths for pedestrians. Rockefeller Jr. had his own visions for the park, believing it should provide striking views of the rock ridges in the distance. Olmsted Jr. agreed, for his design was careful to preserve open areas and included an abundance of colorful plants to compliment the expansive views of the Hudson River. Over the years, restoration on Fort Tryon Park has constantly referred to the original Olmsted Brother’s design. Today, photos from the Olmsted Archives are used for restoration of the Alpine Garden at Fort Tryon Park. Hubbard Park (Meriden,CT)When Walter Hubbard was preparing to donate 1,800 acres of land to Meriden, he knew he wanted to have a heavy say in the layout of the future park. Hubbard also knew the importance of bringing in a professional, so he enlisted Olmsted Brothers to help plan the park that would be his namesake. Hubbard worked specifically with John Charles Olmsted, inviting him to visit the land and make recommendations on its design and layout. After visiting, Hubbard and Olmsted would exchange several letters between 1898 and 1899, and it’s clear that Hubbard seriously considered Olmsted’s recommendations, evidenced by the fact that letters describe in detail the present situation of the park. In their correspondences, the two discussed numerous details like water flow, tree placement, ravines, and ridges, as well as the best areas to take in the views, and settle in for a picnic. Hubbard relied heavily on Olmsted to give the park its rustic style, the trademark of the park. At times, Olmsted and Hubbard butt heads on the design of the park. While both propose a shelter at the east end of the park, Hubbard believes it should be made like a Greek temple, while Olmsted protested that it should be built roughly, with local stones. In the end, Olmsted prevailed in convincing Hubbard of the design. Though Hubbard never worked with Olmsted Sr., he was certainly inspired by the creation of Central Park. When Hubbard gifted the land to Meriden, he specified that everything connected with the park was to remain free of charge. Unlike Olmsted, Hubbard had difficulty planning a park that would have permanent effects. While Olmsted Brothers may have never prepared any plans for Hubbard Park, their suggestions for road and walkway designs live on. Fort Greene Park (New York City, NY)Originally the site for several forts used for the Revolutionary War, after conflict had ended the citizens of the surrounding land began instinctually using the area that would become Fort Greene Park for open space, free to the public. Twenty years after being designated as a parkland, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were engaged in 1867 to prepare a new design for the park, as well as a crypt for the remains of the 11,500 prison ship martyrs; brave men and women who died while imprisoned during the Battle of Long Island. Olmsted and Vaux were likely hired to design the new park because of their growing involvement in creating the parks and open spaces of Brooklyn. Their design approach at Fort Greene called for a park of rural character, consisting of “a series of shady walks that will have an outlook of open grassy spaces at intervals”. In addition to winding pathways and open lawns, there was a designated area for social gatherings, two playgrounds, an observatory, and room for a monument to the prison ship martyrs. While some of these design elements weren’t included at Central or Prospect Park, Olmsted and Vaux included them here, seeing them as appropriate to the site and neighborhood. Though Olmsted and Vaux always intended for a formal monument to the prison ship martyrs, a lack of funding would interrupt its realization. After Olmsted and Vaux had both passed, the architectural firm of McKim, Mead, and White were brought in to complete it. Today, the park retains much of Olmsted and Vaux’s original characteristics, with winding pathways, sloping lawns, and mature trees, including on 135-year old English elm.

Olmsted Archives Branch Brook Park (Newark, NJ)During the Civil War, the area that would become Branch Brook Park was serving as an encampment for several regiments as they prepared to fight in some of the most important battles of the war, from Antietam to Appomattox. In 1867 the war was over and New Jersey State legislature established the Newark Park Commission to locate grounds for a city park. The Commission would ask Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. to visit Newark and recommend the best possible site for park; he choose the Branch Brook area. While Olmsted Sr, along with Calvert Vaux, would envision Branch Brook Park as the Central Park of Newark, it was Olmsted Brothers who would take over the project in 1898, and create a plan for the park. Olmsted Brothers faced challenges immediately, for in the years since Olmsted Sr.’s original recommendation, another landscaping firm had taken over the design, opting for a more gardenesque style with numerous architectural elements, something Olmsted hated and taught his sons to as well. Adapting to these changes, Olmsted Brothers cleverly designed a plan splitting Branch Brook Park into three divisions. The Southern division would incorporate the elaborate gardenesque elements brought in by the previous firm. The Middle division would serve as a transitional zone, mixing exotic plantings with those more natural to the area. The Northern division was the largest, and most naturalistic of the divisions. Olmsted Brothers took some time off from Branch Brook Park but were called in again in 1927 to lay out the two thousand Japanese flowering cherry trees donated to site to rival the trees in Washington, D.C. Laying the trees out on tiered slopes along the river ensured that none would dominate the other, but flow together in harmony.

Olmsted Archives Belle Isle Park (Detroit, MI)In 1881, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. was commissioned by the city of Detroit to transform a small island in the Detroit River into a park. Initially, Olmsted wasn’t too happy with the site selected, stating “conditions could not be more favorable to the breeding and nursing of mosquitoes…[In] the pools…I found discolored, and covered by bubbles and a green scum; and there was a putrescent organic matter on their borders…”Olmsted was contracted by the Detroit for three years, being paid $7,000 for his design. The challenge at Belle Isle was creating a design that would allow for public gathering and recreation while maintaining the natural state of the island. The solution was to place a ferry dock at one end, concentrating all the public facilities at the end. This allowed Olmsted to leave the rest of the island in as natural a state as possible. To remedy the marshy land forming on the low-lying island, Olmsted proposed a system of underground pipes that would lead into canals, which had a dual purpose of being used for pleasure boating. From the start, Olmsted put more investment into Belle Isle than many Detroiters, even waving his normal visitation fees. He hoped to capitalize on the island’s existing wooded area to serve as the park’s central attraction. Unfortunately, Olmsted’s design was deemed too elaborate and, due to disagreements on funds with Detroit’s Park Board, Olmsted resigned from the project and Belle Isle was never carried out to its full extent. Elements of Olmsted’s plan were carried out, like wooded areas and the ferry landing. All of Olmsted’s park designs include three zones- a formal zone, and active zone, and a natural zone, present in Belle Isle Park. The formal zone includes Scott Fountain and Sunset Point, the active zone encompasses cultural attractions and athletic fields, while the natural zone is dominated by the wetland forest.

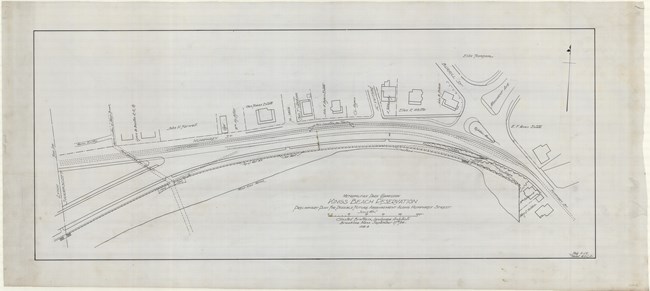

Olmsted Archives Revere Beach (Revere, MA)By 1893, Charles Eliot had been trained by Frederick Law Olmsted, left the firm that trained him, and had returned. It was two years later that Eliot was commissioned, as a member of the Olmsted firm, to create a formal design for a new beach in Revere, MA.Just five miles north of Boston, Eliot would state that at Revere, “we must not conceal from visitors the long sweep of the open beach which is the finest thing about the reservation". Olmsted taught all who entered his office to preserve and enhance the existing natural features of the site they’re working at, and at Revere, Eliot’s design called for restoration of the natural contours of the beach. Rail accesses introduced in 1875 allowed for easy access to an already popular coastline, though Eliot removed all railroads and buildings that impeded the view of the sea. To remedy the removal, Eliot’s design included a boulevard along the length of the shore for several new structures. An already popular coastline began developing as quickly as Eliot could design, with new dance and music halls, hotels, cinemas, and amusement parks popping up. America’s oldest beach, and the first in the United States acquired for the purposes of public recreation officially opened its 4.5-mile crescent-shaped stretch in 1896, with 45,000 people gathering to celebrate.

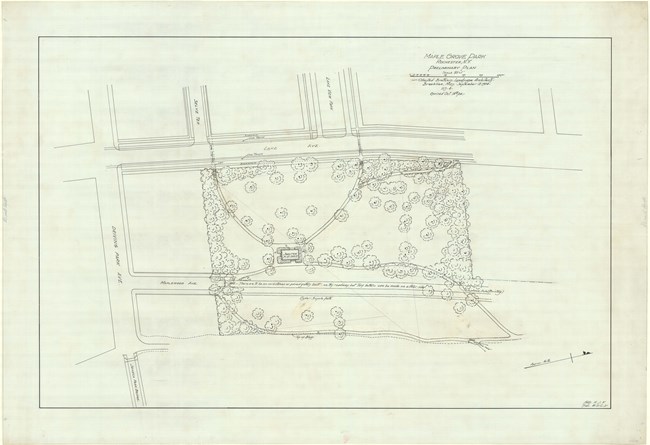

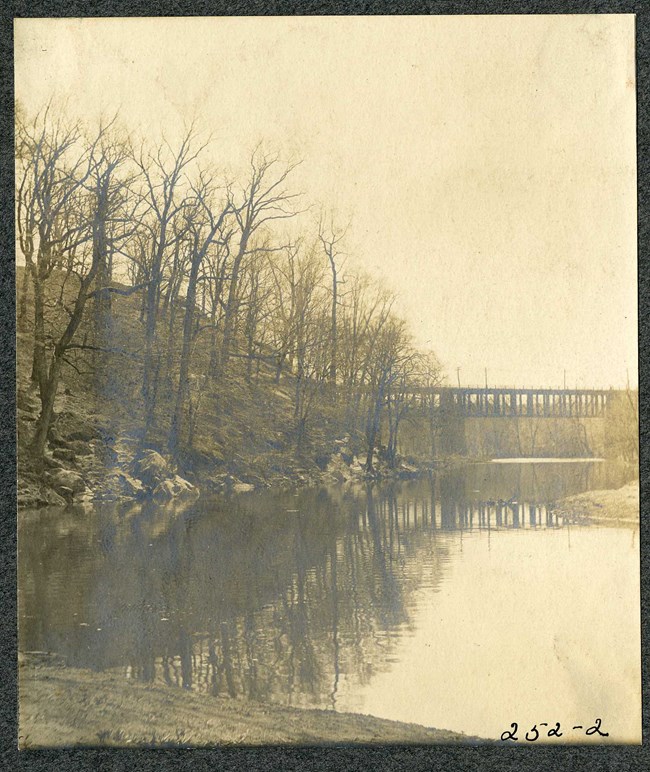

Olmsted Archives Maplewood Park (Rochester, NY)Frederick Law Olmsted was hired by the Rochester Parks Commission in 1888 to turn several acres of generously donated land into an urban park system. Olmsted immediately focused his designs around Rochester’s gorgeous waterways, specifically in his design from Maplewood Park.One of two Olmsted Sr. parks laid out along the Genesee River, Olmsted was continually urging Rochester City leaders to acquire more land along the Genesee River, with the goal of preserving the varied scenery from the threats of industrial development. Olmsted’s design took advantage of the diverse landscape created by centuries of the Genesee River course, running through Rochester. Olmsted described the rolling topography of downtown Rochester as a nearly ideal site to lay out a pastoral landscape. In addition to a pastoral landscape, Olmsted was also able to incorporate a picturesque one at Maplewood Park, in the steep rugged gorged banks of the Genesee River.

Olmsted Archives Mount Royal Park (Montreal, QC, CAN)In November of 1874, Frederick Law Olmsted would make his first official visit to Montreal and view the difficult conditions of Mount Royal. He warned Montreal Park Commissioners almost immediately that the land made it very unlikely a park could be built. Olmsted believed “rugged and broken ground is the last that should be chosen for a public recreation ground in the immediate vicinity of a large city”.The future park was located at a unique site. At the time, Montreal was 200 years old, with a population of 120,000, situated at the foot of a looming pile of rocks a mile long and a half mile wide. Calling it a mountain was generous, as it was only 735 feet high, but some of its sides could get incredibly steep, and surrounded by a countryside with a flat valley, it loomed over Montreal. In his first report to the Montreal Park Commission, Olmsted stressed “the power of scenery to eliminate conditions which tend to cause nervous depression or irritability”. He claimed that a charming natural scenery “acts in a more directly remedial way to enable men to better resist the harmful influences of ordinary town life”. Olmsted truly believed his parks would have a therapeutic effect on all who entered them, where people could enter a cheerfully musing state where the mind is left unoccupied. At Mount Royal Park, Olmsted thought that the mystical effect of this natural landscape would provide city dwellers with a therapeutic release.

Olmsted Archives Washington Park (Chicago, IL)Frederick Law Olmsted would begin advocating for a park and boulevard system in Chicago, Illinois when he visited Chicago during the Civil War. A few years after the end of the war, the Illinois State Legislature would pass three bills in February of 1869 that would create a system of parks and boulevards for Chicago.The approved legislation ultimately led to the formation of the South Park Commission, and the entrance of Olmsted and Vaux. Olmsted and Vaux created their plan for South Park in 1871, however the Great Chicago Fire delayed construction. When construction resumed, South Park was broken into an eastern and western division, 372-acre Washington Park in the west, and 593-acre Jackson Park in the east. While Jackson Park would serve as a lakefront trace, Washington Park, which got its name in 1881 to honor the first president of the United States, would serve as an inland rectangle of prairie lands. Washington Park would be realized according to Olmsted’s design, though he would not be supervising the design. By the late 1880s, about two-thirds of the park had been built under the supervision of landscape architect H.W.S. Cleveland. In the end, Washington Park had a hundred-acre open meadow for sports and gatherings, surrounded by ninety acres of open woods, complete with walking paths.

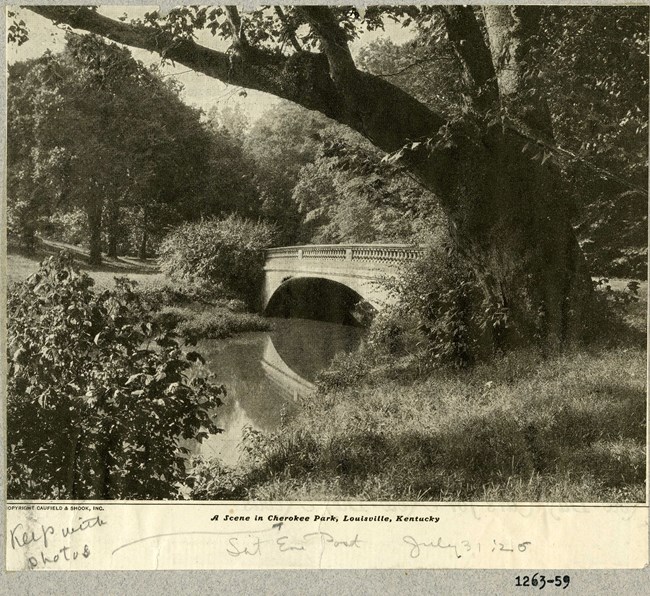

Olmsted Archives Cherokee Park (Louisville, KY)In 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. addressed a group of Louisville civic leaders about establishing a park system in their city. Olmsted’s proposed three park designs around the city’s perimeter: Iroquois, Shawnee, and Cherokee.Each park would reflect one of the region’s distinct native landscapes and at Cherokee Park, that landscape was devoted to more relaxing activities like walking, hiking, and horseback riding. With Olmsted, the Louisville Parks Commission created a network of parks and boulevards and is one of two park systems worked on by all three Olmsted’s. Anchoring this network of parks and boulevards were the three large parks around Louisville’s perimeter, with Cherokee taking up the eastern section. After Olmsted Sr.’s tenure at the firm was over, Olmsted Brothers worked on Cherokee Gardens, Seneca Gardens, and the Alta Vista subdivision, which benefited from borrowing the scenery Cherokee Park offered. In 1974, a tornado struck Louisville and resulted in the loss of thousands of mature trees at Cherokee Park. A massive replanting effort was undertaken, however, to qualify for federal funding, the park had to be restored to its pre-tornado design. To do this, the original Olmsted plants were consulted for the park’s “rebirth”, with 2,500 trees and 4,600 shrubs planted in the restoration effort.

Olmsted Archives Audubon Park (New Orleans, LA)In 1898, John Charles Olmsted undertook his first solo project for his family’s firm, the design of Audubon Park. Olmsted was tasked to transform the swampy, divided flatland into greenspace. Olmsted’s preliminary plan conformed to the topography, grading and drainage of the site.Like his father, Olmsted ensured any architecture in the park wouldn’t dominate, and expressed the idea that any structures in the park be built to conform to the history and traditions of the city. Work on Audubon park echoed the earlier work done at the Back Bay Fens: unifying a site and solving drainage problems by developing a varied watercourse. In the northern section of Audubon Park, Olmsted used fill from the stream bed to grade the flat site into a rolling meadow, which became part of a golf course. Olmsted also included numerous picnic shelters and diverse plantings along the stream banks and curving paths. Today, the 340-acres of Audubon Park follows much of Olmsted’s plan, though his planting recommendations were not implemented. A zoo was developed in the 1930s, with design advice from Olmsted Brothers.

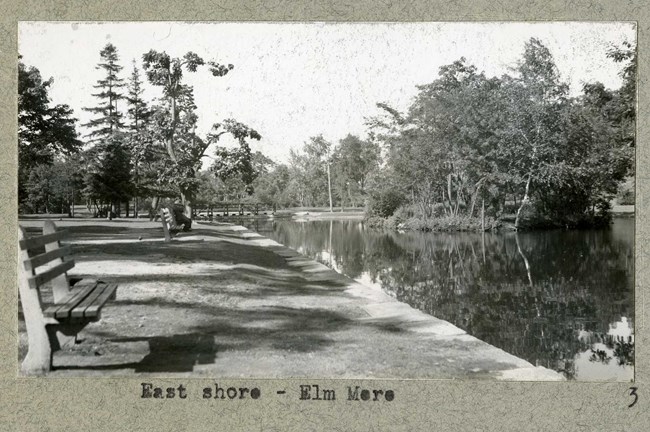

Olmsted Archives Elm Park (Worcester, MA)In 1909, Olmsted Brothers were hired by Worcester to evaluate the city’s parks. From 1910 to 1918, the firm consulted extensively on Elm Park, directing improvements like the addition of bridges and walking paths, new curbing for the ponds, more plantings, and new locations for recreational activities.Olmsted Brothers also helped Worcester acquire nearby Newton Hill, which became an addition to Elm Park, requiring new paths. Despite Olmsted Brothers not beginning work till the early 1900s, the land was purchased in 1854 using public funds, and is often recognized as one of the first purchases of land for a public park in the U.S. After the Great Depression, Olmsted Firm came back to Worcester to work on Elm Park. Between 1938 and 1941, Olmsted Brothers landscapes the triangular plot at the base of Newton Hill that became the site of the Rogers- Kennedy Memorial.

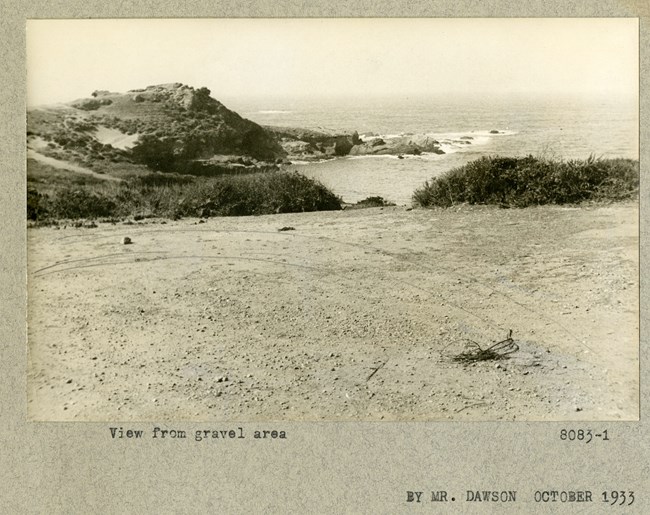

Olmsted Archives Point Lobos (Point Lobos, CA)In 1920, real estate developer Duncan McDuffie, who had already hired Olmsted Brothers to design his estate in Berkeley, again reached out to the landscape architecture firm. McDuffie was a member of the Save the Redwoods League and hired Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to research Point Lobos and report on the most noteworthy areas that needed to be preserved.On his first visit, Olmsted Jr. was struck by how unique the landscape was. Olmsted Jr. noted the outstanding nature at Point Lobos and agreed to assist in the creation of a state park by providing analytical surveys and site plans. Directing the study and visiting Point Lobos frequently during the two years he spent on the effort, Olmsted Jr. described the area as “the most outstanding example on the coast of California of picturesque rock and surf scenery in combination with unique vegetation”. In 1933, the State of California, with assistance from the Save the Redwoods League, purchased 348 acres at Point Lobos.

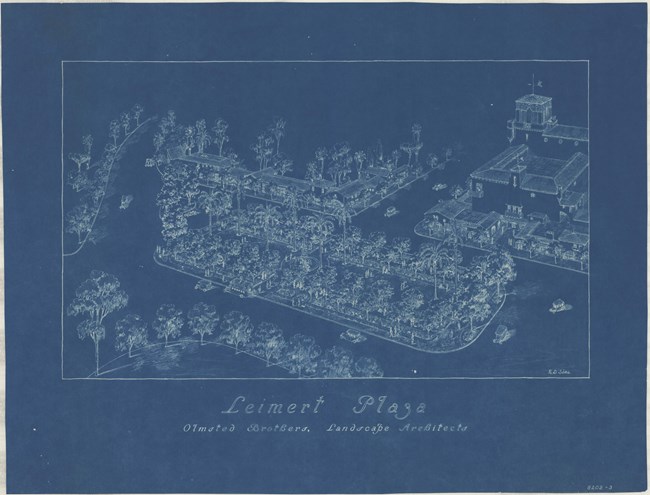

Olmsted Archives Leimert Park (Los Angeles)Named after its developer, Walter H. Leimert, Leimert Park was developed in 1928 and designed by Olmsted Brothers. Leimert Park would serve low- and middle-income family homes in one of Los Angeles’ first planned communities. For its time, it was considered a model of urban planning.Planning features at Leimert Park, both the planned community and the plaza within it included minimized automobile traffic near community hotspots like the church, hidden utility wires, and densely planted trees. These features are often ignored by developers in Southern California. Olmsted Brothers designs included a planting plan, perspective sketches of the whole park, sidewalk and hardscape plans, plans for the plaza fountain and a planting detail to create a garden around the fountain. Olmsted Brothers designed Leimert Park’s Plaza to serve as the public hub for the planned community, which it still does to this day.

Olmsted Archives Leakin Park (Baltimore, MD)Twice in his career, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. issued reports on Baltimore’s park resources, both times recommending expanding existing parks and creating new ones. Olmsted’s goal for Baltimore was to achieve a “roughly equitable distribution” or park amenities for everyone.The star of Olmsted Jr.’s report, Development of Public Grounds for Baltimore, was the concept of the stream valley park, which according to Olmsted Jr., had several advantages. Those advantages included the fact that the scenery along the streams was one of the city’s greatest assets, lowlands could be purchased for a modest price, and in Olmsted Jr.’s own words, a stream valley “cannot be built on, it cannot be left in irresponsive private hands, but it can be used to great advantage for park purposes.” In 1939, Olmsted Jr. reported to Baltimore that he had examined the roughly hundred sites the city had put as the next park and had chosen Leakin Park. He reminded Baltimore officials that Leakin Park must be in a neighborhood where recreational space was lacking, and that the park should provide diverse activities for people of differing ages and social classes. In addition to supporting Leakin Park, Olmsted Jr. explained why certain parts of the city shouldn’t be considered for a new park. Acquiring land in the inner city would be too costly, and while the eastern portion of the city needed a park, declining population was the reason Olmsted didn’t believe a park could work there. In the end, Olmsted Jr. was correct in picking Leakin Park, which became Baltimore’s largest park, and one of the largest wilderness woodland parks on the East Coast.

Olmsted Archives Mill Creek Park (Youngstown, OH)In 1891, a Youngstown Ohio native wrote to his state’s legislature, enabling the establishment of a park in his hometown. The state approved his request and began reaching out to the most reputable landscape architecture firm in the country.It was Charles Eliot who received the first call from Youngstown about designing a park. In 1892, Eliot wrote to Youngstown Park Commissioners stating that “your gorge is one of the finest park scenes in America and deserved more careful handling”. Until his untimely death in 1897, Charles Eliot assisted in laying out drives and trails highlighting the most dramatic natural elements of the 440-acre gorge. A close friend of Eliot’s, Warren H. Manning would be the next consulting landscape architect at Mill Creek Park. After being a member of the Olmsted Firm for nearly eight years, Manning left to start his own landscape architecture practice, and would be called on by Youngstown from 1920 to 1932. Manning’s design would extend the park significantly to include Bear Dens and abandoned sandstone quarry sites. Manning also included two more sandstone bridges and a shelter for the park. In 1948, Olmsted Brothers was again called on by Mill Creek Park, this time to add a second active sports area, which would be over 65-acres. In their design, Olmsted Brothers included open play areas surrounded by wooded margins.

Olmsted Archives Edward Bok Sanctuary for Birds (Mountain Lake, FL)When Dutch immigrant Edward W. Bok spent the winter of 1921 in Mountain Lake, Florida, he climbed one of the highest hills he could find, and once at the summit, the idea came to him to preserve this hilltop and create a bird sanctuary on it- a place of beauty, serenity, and peace.Having made the arrangements to purchase the hilltop, Bok commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to transform this arid sandhill into “a spot of beauty second to none in the country.” In 1923 Olmsted Jr. began working to turn the area into the most beautiful garden sanctuaries. The first year of work was spent digging trenches and laying water pipes for irrigation. Only after this step could rich black soil be brought into the area through thousands of loads. Olmsted Jr. spent the next five years working diligently with his team to plant a mix of native and exotic plants that would thrive in a humid climate, lending a tropical feel to the native oak hill. Olmsted Jr. carefully selected plants that would provide a hearty supply of food and shelter for migrating birds and other wildlife in the area. In total, Olmsted planted 1,000 large live oaks, 10,000 azaleas, 100 sabal palms, 300 magnolias, and hundreds of fruit shrubs like blueberry and holly. |

Last updated: June 26, 2024