Viewpoint

Preserving Ranches: Not Only Possible, but Imperative

by Ekaterini Vlahos

It is not necessarily those lands that are the most fertile or most favored in climate that seem to me the happiest, but those in which a long struggle of adaptation between man and his environment has brought out the best qualities of both. —T.S. Eliot in After Strange Gods |

Silhouettes of cowboys and ranches nestled into vast panoramic landscapes are powerful icons of America's Western heritage. Traditional ranches are places where struggle and adaptation have etched themselves into the ground, weaving together culture, land, buildings, homes, and lives. Ranches exemplify where the natural and manmade have collided and grown together, forming a vernacular cultural landscape over generations.1

A ranch is much more than the buildings that dot its landscape. It is the ranching culture, the people, the land, and the built environment coming together. The cultural landscape of the American West is embodied in the ranch and its traditions. However, Western ranches are threatened by escalating property taxes, a lack of economic viability, estate taxes, urban sprawl, and deteriorating structures. Preserving the ranching culture and ranches of the American West is imperative if we are to reverse these threats.

What Defines Ranches of the American West?

Traditional ranches are a settlement form that is unique to the American West and reflect cultural traditions that influence the building forms and land use. They are generally characterized by large acreages and disproportionately small numbers of structures. Typically, the landscape is altered and the structures comprise reused, recycled, and relocated materials and buildings that support the necessities of the ranching way of life.

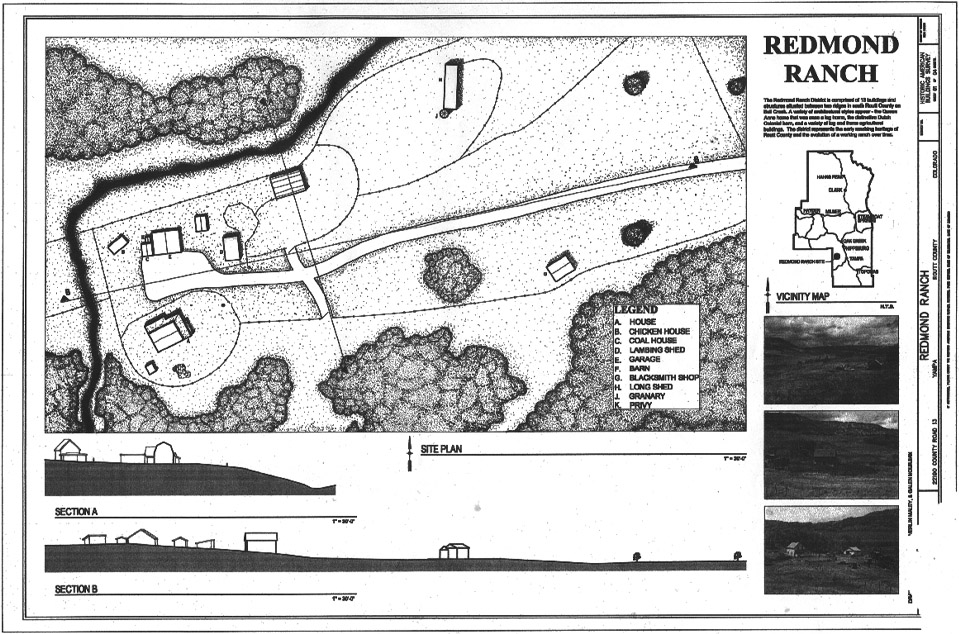

The ranch complex generally includes a main house, often the original homestead expanded over time; a bunkhouse for ranch hands; a barn; a blacksmith shop; garages and storage sheds; and small outbuildings such as a privy, meat house, icehouse, and a cabin in which a teacher might reside. Landscape features include corrals, fences, hay stackers, wells, hay meadows, and grazing land.(Figure 1)

Ranches in Colorado are excellent examples of vernacular settlements that reflect changing regional patterns in growth, economics, development, and agriculture. Many remain from the original homesteading claims, passed down through generations in families who continue to work the land.

Why Preserve Ranches?

As a cultural resource, ranches represent an important aspect of the West's history and early settlement patterns. They have evolved and developed as unique land-use systems. Ranching activities, the spatial organization of the ranch complex and its relationship to the land, cultural traditions, vernacular architecture, and circulation patterns for livestock and people, all exhibit the history of living off the land. Traditional ranches convey early settlers' efforts to build and shape the environment for a specific use in areas that were often considered remote and uninhabitable.

Ranches also have real value as healthy environments of biodiversity, open space, wildlife hubs, and aesthetics that are unique components of this region's identity. The ranch illustrates one of the more successful ways in which people in the West coexist with natural landscapes. With the passing of each ranch, we lose a piece of history, a link to our Western heritage, and a connection to the land that we often take for granted. We can preserve these cultural landscapes, either by protecting their economic viability or by setting them aside. Preservation of the ranching culture and ranches is not only possible; it is imperative.

Pressures on Ranchlands

The American Farmland Trust has identified approximately five million acres of threatened prime ranchland in Colorado. The properties include the largest tracts of private land surrounding Denver and Colorado Springs, which are considered ideal places for accommodating urban growth. The potential loss of land to development is the greatest threat to the long-term feasibility of ranching in Colorado.

Until the last decade, Colorado's Front Range was a landscape dominated by traditional ranches. Today, the transfer of ownership from traditional ranchers has put pressure on the viability of ranches in the area.

Three main types of ownership changes are taking land out of the hands of the region's traditional ranchers. Different preservation models are emerging from each approach. The first type transfers ownership to an advocacy group that acquires ranchland to preserve the biodiversity and open space. The second type purchases ranchlands for natural resources and recreation by government agencies, such as the Colorado Department of Wildlife, the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, and individual counties. In the third type, private buyers purchase ranches for recreation and development purposes with little interest in the activity of ranching. The move away from ownership by traditional ranch families is forcing a notable alteration in the cultural landscape of the West. This shift affects not just the ranches themselves but also the people, culture, and the entire landscape of which ranches are an intrinsic part.

Ranching to Environmental Conservation

Ownership of several ranches has moved from traditional cattle ranchers to advocacy groups and nonprofit environmental organizations in recent years. These groups and organizations recognize that ranches are critically important for their landmass, biodiversity, and complex ecosystems. The Nature Conservancy alone has conserved in perpetuity over 100,000 acres of Colorado ranchland.

Transitioning ranchlands into the stewardship of advocacy groups generally affects one or more of the essential elements that define a ranch: the culture, the land, or the structures. More often than not, the transfer in ownership brings an alteration in the cultural landscape. A change in the type of livestock or its complete elimination transforms the vegetation, land use, and small-scale elements such as fencing and corrals that contribute to the ranches' identifiable landscape. In most cases, ranching is no longer the heart of the operation. The buildings are often vacated or adapted to uses that support the organization's mission. Even though ranch complexes are often historically significant and in many cases are listed in the state historic register or the National Register of Historic Places, they are generally viewed as separate from the land, often with easements around a ranch complex to separate the complex from the land-conservation component regardless of the entire context.

Efforts to conserve land for its biodiversity are commendable and essential for ecologically healthy landscapes. One way to achieve this goal is to preserve the way of life that has successfully protected natural communities, working with local ranchers to keep agricultural land economically productive and healthy. Oftentimes, however, the ranching culture that once dominated and influenced the region is no longer an integral part of the land use.

Ranching to Open Space and Recreation

In addition to advocacy groups, government agencies have an interest in ranchlands for their natural resources and recreation opportunities. In 1997, for example, approximately 7,000 acres of historic ranchland—11 percent of all privately held land in Lake County, Colorado—went on the market. The ranches and open space that surrounded this land were critical hubs for wildlife, with migration corridors, spawning beds, nesting sites, and foraging grounds for over 250 species. The land also encompassed scenic viewsheds, significant cultural resources, and recreation areas.

Lake County enlisted federal, state, and local agencies, and organizations that shared the common goals of public education, wildlife habitat protection, the stewardship of land and water resources for open space, historic preservation, smart growth, and outdoor recreation. Initial collaboration led to the formation of the Lake County Open Space Initiative. Through shared preservation efforts, natural resources in the county have been conserved and open space made available for public recreation for the first time.

Again, while commendable, this has led to the loss of the traditional ranch. The shift in the land use, including the removal of livestock and haying activities, will change the cultural landscape as the vegetation returns to its "natural" state. The historically significant ranch complex has been parceled off from the surrounding land and the buildings are vacant. New owners will eventually manage the ranch complex independent of the land use.

Efforts to conserve the ranch for its resources and recreational value, as well as to maintain critical open space, are significant and add to a county's or region's economic health. In addition, the creation of public recreational opportunities contributes to quality of life that drives job creation and population growth, all of which contributes to the county's economic health. However, the ranching culture that once dominated and influenced the region is no longer an integral part of the entire landscape. The ranches represent the county's bygone history. The cultural landscape will continue to evolve, unfortunately devoid of the central way of life that once defined the county or region.

Ranching and Preserving a Way of Life

In response to private buyers' purchasing ranches for recreation and development, grassroots preservation programs are forming throughout Colorado to save the traditional ranch from extinction. Participants come from a community of interested ranchers and local citizens whose goal is to protect rural areas and their way of life. The grassroots method has proven to be the most successful at truly preserving ranches. Participants are keenly aware of the importance of those who work the land, the evolving ranch culture, and the structures and buildings at the heart of the operation as integral to parts of the whole cultural landscape. In addition to preserving individual properties, there is an understanding of how each property fits into the entire agricultural context of the region. Although each individual ranch may not be considered significant for historical designation, as a collective whole, they represent the evolution and heritage of working ranches. The ranches tie together the buildings, the land, and the culture that identify a region.

The success of ranch preservation programs depends on partnerships among the ranchers, communities, local preservation groups, land trust organizations, and institutions of higher education. Communities that are threatened with the loss of their agricultural lands are prompted to evaluate current zoning, development and planning easements, estate taxes, and tax incentives. Partnerships, zoning, and tax strategies can help families keep agricultural lands in production.

Through the University of Colorado at Denver, graduates students in architecture, landscape architecture, and planning are engaged in hands-on preservation processes, helping ranchers and property owners with surveys and inventories. The surveys are used for nominating properties for historical recognition, completing historic structure assessments, documenting ranch complexes, writing grant proposals, securing preservation easements, and researching tax and other incentives.(Figure 2)

The grassroots programs are incentive-based and allow owners to select options that best suit their needs. The programs ultimately allow for local historical designation of as many ranch properties as possible. For many rural areas, obtaining the information needed to determine the viability of preserving ranchlands is difficult and costly. Grassroots programs ease those burdens of such costs and provide property owners with options and information that can help preserve their ranches for future generations.

The Necessity of Western Ranches, Preservation, and Understanding

The preservation, reuse, and interpretation of ranches by advocacy groups and government agencies help in building public awareness of the history of these rural sites. However, the methods used by these groups—the purchase of the ranchlands for biodiversity, open space, and recreation—preserve the lands, but fall short of preserving a seamless cultural landscape and a living ranching culture.

Carrying on the traditional ranching way of life will have the greatest impact on preserving this vernacular cultural landscape. Those who created and still occupy traditional ranches take pride in their way of life, recognize the threats, and are beginning to demand active roles in the preservation and management of their lands, many of which are ultimately historic properties.(Figure 3)

Figure 3. "The Redmond Ranch is a significant property for the ranching community in Northwestern Colorado. This family-owned ranch is a reflection of the early agricultural development of South Routt County. The ranch serves as a representation of the significant role that high country farming and ranching played in the development of the region. The Redmond Ranch individually serves as a metaphor for and exemplifies agriculture in Routt County through the homesteading and settlement period, during the agricultural activity in the 1920s, and the continuation of the ranching life-style in the area. The Redmond Ranch, more than any other community ranch, tells the story of agriculture in South Routt County and the varied range of activities that occurred on the site. The Redmond family is planning conservation easements, and have completed architectural inventory surveys, HABS drawings, and historic structural assessment and historic designation at the local and state register of historic places."—Laureen Schaffer, Redmond Ranch Nomination, Colorado Historical Society, Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Preserving ranch complexes or single buildings as artifacts, devoid of landscape context and culture, is not a suitable preservation approach for Western ranches. Preservation must be broadened to understand the dynamic nature of ranches and to embrace change of culture, structures, and land as essential components to preserving the ranch. The rancher and ranch play a major role in this landscape evolution, making it essential to plan for the protection and management of the ranches, and to understand the significance of this culture—how it impacts our landscapes and informs our future in the West. As ranching landscapes are altered, as ranches change ownership, and as ranching culture evolves and in many cases disappears, such changes begin to redefine the landscape of the American West.

About the Author

Ekaterini Vlahos is a professor of architecture at the College of Architecture and Planning, University of Colorado, Denver. She can be reached at k.vlahos@comcast.net or ekaterine@stripe.colorado.edu.

Note

1. I would like to acknowledge the organizations throughout Colorado with which I have had the privilege to work in addressing issues of ranch preservation. In a collaborative effort with South Routt County, my students, the community, ranchers, ranchers on the Barn's Etc. board, and historic preservation professionals between 2000 and 2004, 12 ranches have received local historical designation, 2 have received state designation, 8 have been documented to Historic American Buildings Survey standards, and approximately 80 ranches have been surveyed. This is testament to the success of the grassroots method of preservation. (See also Ekaterini Vlahos, "Documenting and Saving the Historic Ranches of Colorado" Vineyard: An Occasional Record of the National Park Service Historic Landscapes Initiative III, issue 1, [2001]: 9-12.) I would also like to acknowledge the Nature Conservancy and partners for their work on the Medano-Zapata Ranch, which has been invaluable to the conservation of over 100,000 acres of ranchlands in Colorado, and for their ongoing efforts to support the ranching culture and preservation of the vernacular architecture of the area. Lastly, I have had the opportunity to work with several government agencies to develop collaborative efforts for the transfer of ownership and preservation of key ranchlands. All of these groups have been invaluable to the development of my research on preservation issues in the West and the study of vernacular ranch settlements in Colorado.