Exhibit Review

Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education

Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History, Washington, DC. Curators: National Museum of American History, Behring Center, staff

May 2004-May 2005

Marching Towards Justice: The History of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution

Law Library, Howard University School of Law, Washington, DC. Exhibit director: Lawrence C. Mann

May 3-July 29, 2004

Museums commemorating the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education face three significant challenges. The first is the need to explain the larger context in which the fight to end segregated education occurred and the steps individuals and agencies took to resist desegregation. Covering Jim Crow, white supremacy, and the denial of constitutional provisions for equal protection is a lot to ask of the introduction to an exhibit. Second, the story leading up to Brown is legally complex and involves a national coalition, led by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) that brought five cases to the federal court system. Finally, the story continues through the immediate aftermath of Brown and the unforeseen consequences of ending the Jim Crow caste system. Today, any celebration of the Brown decision is bittersweet, given mounting evidence of broad patterns of ethnic and economic resegregation within the nation's public schools.

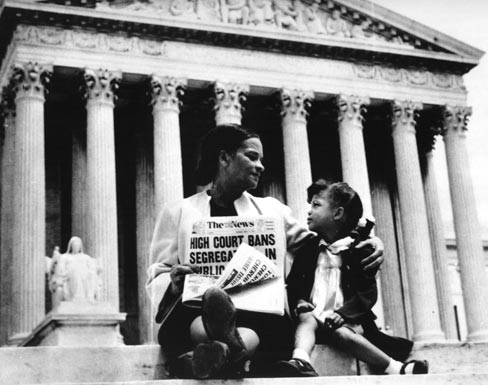

Separate is Not Equal: Brown v. Board of Education at the National Museum of American History provides an interesting mix of artifacts and furniture, original documents and reproductions of well known images, as well as archival television and film coverage. The historical context is provided in objects and documents that depict "Segregated America" ranging from a sign, "Japs Keep Moving," to a campaign poster from Senator Strom Thurmond's presidential bid in 1948. A period film depicts the unequal conditions found in segregated school systems. The legal campaign to combat segregation is portrayed in a series of alcoves that tell the story of the five cases brought together under Brown.

To underscore the landmark qualities of the Brown decision, the exhibit uses four photographically reproduced columns to form a triumphal arch through which the visitor approaches an imposing wooden form, meant to represent a judge's bench. Almost lost in the background as reports of the decision flash on a vintage television, is a portion of the lunch counter and seats from the Woolworth's in Greensboro, North Carolina, site of a major 1961 sit-in. Visitors are left to ponder the relationship between the judicial end of segregated school systems in the mid-1950s and the struggle to integrate public accommodations in the early 1960s. A brochure and the museum's website provide complementary interpretation.

Marching Towards Justice: The History of the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides an interesting contrast to Separate is Not Equal. Marching Towards Justice is the first in a series of exhibits called Brown @ 50: Fulfilling the Promise. Sponsored by the Damon J. Keith Law Collection of African-American Legal History, Wayne State University Law School, the traveling exhibit has been displayed at over a dozen institutions and conferences. Installed in a curved, well-lit space at the law library at Howard University's School of Law, the exhibit uses a variety of familiar images with some audio supplements to tell the story.

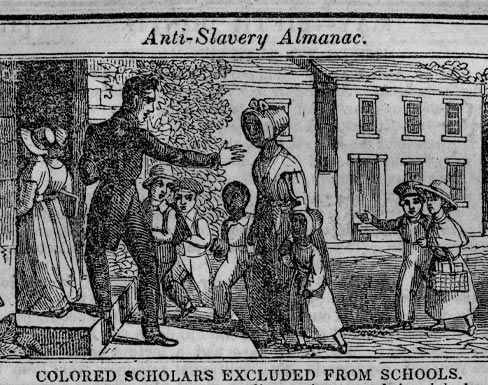

The exhibit's "central focus is the courageous struggle of persons of African descent and their allies who, for several centuries, fought to achieve justice in this land." With such an expansive mandate, it must sketch the story of the 14th Amendment with broad strokes. Marching Towards Justice outlines the events prior to and following the ratification of the 14th Amendment—from the arrival of Africans in America and the paradox of slavery, through the Dred Scott case to the establishment of equal protection during Reconstruction and Plessy v. Ferguson, the promise denied during the Jim Crow era, leading up to Brown. The chronology is supported by drawings and photographs, as well as a historical narrative steeped in the social and cultural history of African Americans.

The exhibit concludes with the half-century civil rights struggle leading up to the Brown decision in the mid-1950s. The exhibit lays out the legal strategies and highlights the participants, including attorneys Charles Hamilton Houston and Thurgood Marshall, in the NAACP's attempt to achieve the Constitution's promise of equal access and opportunity. The exhibit's thesis, that the 14th Amendment "ultimately becomes the weapon of choice" [emphasis in text] during the 20th century for legal battles with institutionalized racism, is well illustrated. A companion booklet provides additional context for the story as well as supplemental bibliographic resources for those interested in a more detailed discussion.

Both exhibits are worthy and successful, each within their own context, sponsorship, mission, and venue. Separate is Not Equal and Marching Towards Justice correctly highlight the contributions of individuals, especially Houston and Marshall, in championing school desegregation in the nation's schools. One can only imagine the bravery and anguish of countless, unrecognized parents who knowingly placed their children in harm's way and who risked their own lives and livelihoods to openly confront segregation. Looking back on Brown, as the story passes from active memory to museum installations and historic sites, we can hope that these important events receive the consideration and stewardship they deserve. For the preservation community, exhibits that commemorate the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education should serve to awaken us, as Thomas Jefferson noted, "like a fire-bell in the night," that the most important stories of the 20th century are often told not in architectural landmarks, but in common, seemingly unremarkable, places.

John H. Sprinkle Jr.

National Park Service