Last updated: April 25, 2022

Article

Battle of the Bark

NPS Photo

From evergreen, to deciduous, to solidified in rock, trees are a big part of the national park experience. Some parks are dedicated to giant trees like sequoias and redwoods, and others let historic monuments or canyons take the spotlight. Either way, our woody friends offer shade, food, beauty, and a look into the past, but what makes one tree better than the other—we'll let you decide who to “root” for!

Check out our iconic trees below and find your favorite!

NPS Photo

Agathoxylon

Scientific Name: Agathoxylon cordaianumDinosaur National Monument

Herbivore long necked dinosaurs were likely chomping on many of the tall trees when they lived in what is now Dinosaur National Monument 150 million years ago. Camarasaurus had a head that reached up to 25 feet off the ground and could feed on high tree branches, where other dinosaurs like Apatosaurus and Diplodocus fed on shorter trees. Some of the wood we find in the park show that these trees were also being munched on by prehistoric beetles! While no fossil beetles have been found in the park, we do find the traces they left behind when chewing on wood. These kinds of fossils are called trace fossils. Other plant fossils in the park include tree branches, "pine" cones, and seeds.

Learn more about fossil trees in Dinosaur National Monument.

NPS Photo

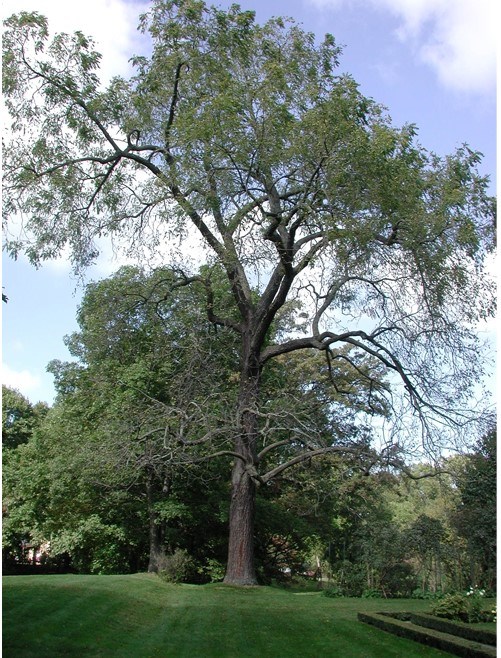

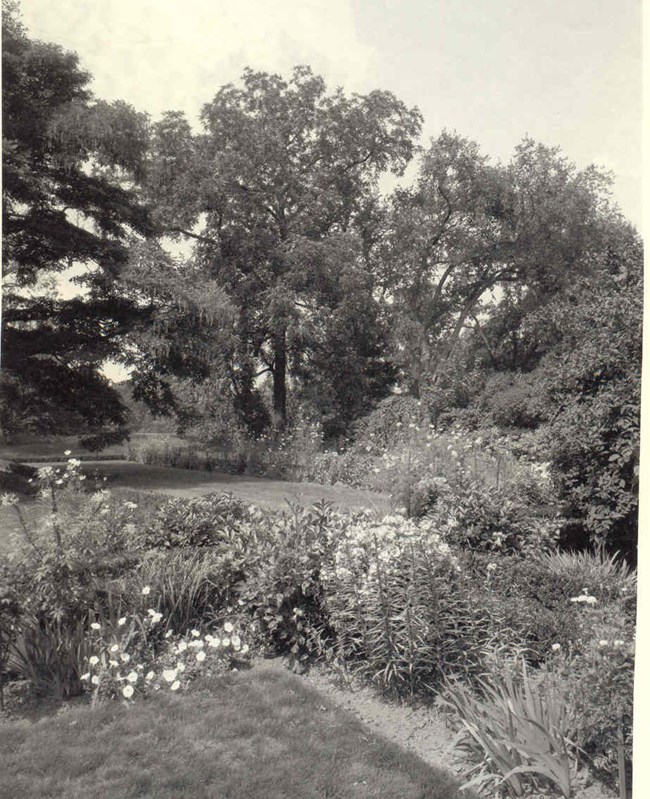

Black Walnut

Scientific Name: Juglans nigraAdams National Historical Park

Adams National Historical Park features a Witness Tree, which is a tree that bears witness to historical events. A still-living black walnut planted by John Quincy Adams witnessed his preparation for the defense of the Amistad Captives, his re-election loss to Andrew Jackson as president in 1828, and his election to the House of Representatives. In total, the sturdy black walnut watched the victories and downfalls of three generations of Adams’.

NPS Photo

Learn more about Adams National Historical Park.

NPS Photo/Shaina Niehans

Coast Redwood

Scientific Name: Sequoia sempervirensRedwood National and State Parks

Redwood National and State Parks has coast redwoods, or Sequoia sempervirens. These are the tallest trees in the entire world and are only found along the north coast of California and southern Oregon. Growing from a seed the size of a tomato seed, these trees can grow to the impressive height of 380 feet (115 meters) and have a width of 22 feet (7 meters). But these forest skyscrapers offer so much more than a height advantage. Hundreds of thousands of years of evolution have made them one of the best adapted trees in the world.

Photo Credit: Save the Redwoods League

Learn more about where coast redwoods are found, how shallow roots support giant trees, what animal’s DNA can be found inside of coast redwoods, and so much more at Redwood National and State Parks.

NPS Photo

Dawn Redwood

Scientific Name: Metasequoia

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument

John Day Fossil Beds National Monument was once home to the Metasequoia, also called Dawn Redwood, which is a living fossil! The Metasequoia is a small cousin of the coastal redwood and giant sequoia trees found in California. It is also the Oregon state fossil.

In the Bridge Creek Assemblage, 33 million years ago, the Metasequoia was a common conifer in forests along streams and lakes in this region. As the climate became cooler and drier, the Metasequoias slowly disappeared from this area, eventually vanishing five million years ago. Their fossils have been found throughout North America and in parts of Asia since 1855. Then in 1941, a small grove of living Metasequoia trees were discovered in Central China!

NPS Photo

A living fossil is a plant or animal that is first discovered and named from fossil evidence – before the discovery of the living organism. This discovery of “living fossils” is an important way for scientists to gain insight into ancient environments. Fossils of this tree are visible at the Thomas Condon Paleontology Center in the Sheep Rock Unit.

To learn more about the Metasequoia and other plant fossils by visiting Bridge Creek.

Giant Sequoia

Scientific Name: Sequoiadendron giganteum

Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks

If you want to see the world’s largest living trees, visit Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks! These two parks are located in the southern Sierra Nevada and have the greatest range in elevation of any national park in the lower 48, from a mere 1,370 feet in the foothills to a lofty 14,505 feet at the summit of Mount Whitney!

NPS Photo/Rebecca Paterson

NPS Photo/Rebecca Paterson

Giant sequoias grow in the middle elevations along the mountains’ western slope. This region is their only natural range, and the only place in the world where they have grown to such impressive sizes. Giant sequoias can be as much as 36 feet in diameter and 300 feet tall and may be as many as 3,000 years old! While there are taller, wider, and older trees to be found on the planet, giant sequoias are the largest by volume altogether. While you can see giant sequoias on other public lands nearby, including Yosemite, Sequoia National Park was founded specifically to protect these ancient giants. There are more than 30 groves within the boundaries of Sequoia and Kings Canyon National Parks!

Learn more about giant sequoias, including the threats they face, and the ongoing work to ensure their continued survival.

Photo Credit: Rebecca Miller

Great Basin Bristlecone Pine

Scientific Name: Pinus LongaevaGreat Basin National Park

The three main groves of Bristlecone Pines are located at the base of Wheeler Peak, on Eagle Peak, and just east of Mt. Washington. The conditions in which they live are harsh (with temperatures that drop well below freezing), a short growing season, and high winds that twist the trees into almost human-like forms along their limestone ridges. Because of these conditions the Pinus longaeva grow very slowly, and in some years do not even add a ring of growth.

Fun facts:

• They are the oldest non-clonal species in the world and can live for thousands of years.

• They grow so high on the mountains that they can avoid rot, insects, and wildfires (for the most part).

• They have lived through whole eras of human civilization.

Photo Credit: Charles Reed

Visit Bristlecone Pines to learn more about these awesome Great Basin National Park trees.

NPS/OCLP

Littleleaf Linden

Scientific Name: Tilia cordataLongfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site

Though there are several beautiful trees in the two-acre plot that makes up Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters, there is none quite as beloved as the two-hundred-year-old Littleleaf Linden that dominates the East Lawn. Standing at eighty-two feet tall, with a forty-foot spread and heart-shaped leaves, this Linden has grown well above the average of its species.

NPS Photo

To learn more about the Longfellow’s beloved Little Leaf Linden, including the tale of a pruning miscommunication that left Henry and his wife, Frances, “wretchedly disturbed” and “heartbroken” visit Littleleaf Linden at Longfellow House.

NPS Photo

Longleaf Pine

Scientific Name: Pinus palustris

Big Thicket National Preserve

Big Thicket National Preserve is home to the longleaf pine, a tall tree with long needles and large cones. This distinct conifer was once the dominant species in the upland pine forests and wetland pine savannahs of the thicket. Longleaf pines are very resistant to fire and depend on it for the overall health of their habitat, which is home to many endangered species including the most endangered snake in the U.S.—the Louisiana Pine snake, as well as the red-cockaded woodpecker and the gopher tortoise.

Longleaf pine forests used to stretch along the southeastern United States’ coastal plain from Texas to Virginia. Unfortunately, years of logging, fire suppression, and development have reduced those forests to about 3% of their former range. Often replaced by the loblolly pine, this critical habitat has been changed dramatically, at the detriment of many animal species.

NPS Photo/Andrew Bennett

In an effort to restore longleaf pine forests to the area, Big Thicket National Preserve plants thousands of longleaf pine seedlings each year with the help of volunteers and partners. The preserve also has an active fire program that conducts controlled burns in the longleaf pine forests to encourage new growth.

Today, visitors to Big Thicket can see majestic longleaf pines, tall and small, on several trails in the preserve.

NPS Photo

Northern White Cedar

Scientific Name: Thuja occidentalis

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore

Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore is home to a grove of ancient trees which are believed to have survived the area’s logging boom in part due to their natural “armor”.

While oral histories share a few potential reasons that these northern white cedars are still with us, one may surprise you! Located on southwest side of South Manitou Island, these trees have been pummeled by incoming Lake Michigan storms year after year—for centuries. When the wind blasted across the dunes and into the trees, it filled the crevices of their bark with sand. This made it very tiresome and tedious for lumbermen to try to work saws through the sand-filled bark, as they would have to stop often and sharpen the blades by hand. And if the sand wasn’t enough, there’s the terrain—the dunes in the area surrounding the grove are very steep.

NPS Photo

On South Manitou Island you can visit the Valley of the Giants. This is a grove of old-growth northern white cedars estimated to be over 500 years old. Their age is rare for our region because of the intensive cutting for cordwood and lumber in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

To learn more about the forests of Sleeping Bear Dunes, explore the old growth cedars and South Manitou Island.

Oregon White Oak

Scientific Name: Quercus garryana

Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

Find two large Oregon White Oak trees on the Parade Ground to the southwest of the Visitor Center.

Oregon white oaks are one of the most easily identifiable trees at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. They are an important part of many stories here, from the presence of Indigenous peoples since time immemorial to the establishment of the US Army's Vancouver Barracks. Indigenous peoples’ burning practices carved this open prairie out of the surrounding, dense, coniferous forests. The prairie where Fort Vancouver sits today, named Skichutxwa by the Peoples of the Lower Columbia, is an example of Oregon white oak woodlands that had been maintained through controlled burn practices. These iconic trees are an integral part of the ecosystem and have remained due to their thick bark making them resistant to fire.

Photo Credit: Jonathon E. Kraft Photography

Oregon white oaks provide food and shelter for over 200 species of native wildlife and can also produce more than 1000 acorns per year! Today, the National Park Service works to preserve the remaining Oregon white oaks, which may date back to the 1850s.

To learn more about Oregon white oaks at Fort Vancouver, visit our plants page.

Pinyon Tree

Scientific Name: Pinus edulisGrand Canyon National Park

From tall to small, pinyons (or piñons) are excellently adapted to their environment. When areas are rich in water, they can dwarf nearby Utah junipers, topping out at 45 feet. By contrast, if the area is more arid and unforgiving, you will find the tree almost shrub-sized, a mere 10 feet tall. But it is what is underground that impresses. Their extensive root system mirrors the size of the visible tree. Tap roots can extend 40 feet down and sprawl out equally as far, reaching hard to find sources of water. Additionally, their growth rate is slow; a 10-foot tree may be 100 years old!

NPS Photo/Michael Quinn

For visitors, one crucial function of a pinyon is providing shade during the hot summer months. Check out our website to learn more about the pinyon and other trees at Grand Canyon.

NPS Photo/Rick Ruess

Ponderosa Pine

Scientific Name: Pinus ponderosa

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument

Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument has ponderosa pines—a lot of ponderosa pines. The monument is right in the middle of the largest ponderosa pine forest in the world! Here, ponderosas grow slowly, limited by Arizona's dry climate and the rocks of the lava flow. A thousand years ago, when Sunset Crater Volcano erupted, it buried hundreds of square miles of the forest in lava and cinders. For years afterward, little to nothing grew on the rocks.

NPS Photo/Owen Ellis

The ponderosas growing here are evidence of many other plants growing among the rocks. Lichens and mosses came first—simple plants without roots, they can grow on barren rock more easily than trees. Eventually, as generations of those small plants grow and die and decay, soil begins to accumulate in the cracks and crevices of the lava flow. Ponderosas do well in thin, rocky soil, so this is a perfect environment for them!

Because of the time it took for soil to develop, and the hundreds of years that a ponderosa can live, it’s possible that some of the trees out there today were the first to grow on the lava flow. Imagine the changes those trees have seen!

To learn more about ponderosa pines and other plants, visit the plants page at Sunset Crater Volcano National Monument.

NPS Photo

Sitka Spruce

Scientific Name: Picea sitchensisSitka National Historical Park

Alaska's state tree, the Sitka Spruce, signifies energy, tranquility, protection, good luck, as well as sky emblems and northern directional guardians. It can be found growing mostly in moderate rainforests of the Pacific Northwest. Due to the climate of the region, forest fire is not a major danger to these trees. Some Sitka spruce have lived 700 years. Spruce usually has few knots making it perfect for creating musical instruments like piano, harp, lute, and guitar. The wood is generally light and soft while also being strong and flexible so it’s ideal for plywood, shipbuilding and general construction uses.

The Wright brothers' Flyer, like many aircraft before World War Two, was made of Sitka spruce, as were sailboat masts and spars, aircraft components, and the nose cones of Trident missiles.

NPS Photo

Follow this link to learn more about the uses of the trees at Sitka National Historic Park.

Southern Live Oak

Scientific Name: Quercus virginianaGulf Islands National Seashore – Naval Live Oaks, Fort Pickens, Fort Barrancas, and Davis Bayou Areas

Known as “live oaks” for their ever-green properties, Quercus virginiana is native to the southern region of the United States and is commonly found in Gulf Islands National Seashore. The live oak is known for its impressive size, heartiness, and density.

A live oak can grow up to 80 feet tall, spread its branches more than 120 feet across, and its roots can span 90 feet. The lower sections of the trunk are generally short and stout, with its upper sprouting large branches in every direction. Its leaves are small and oval-shaped with a leathery texture. The dramatic spread of its branches provides ample shade while also serving as a barrier in high winds. The live oaks’ tendency to grow along the coast means it has adapted to tolerate blustery conditions, sandy soil, and salt spray. Some live oaks, like those found on barrier islands, exhibit evidence of salt pruning. The excess salt slowly kills the leaves and branches closest to the Gulf, creating a hedge-like effect. This causes the trees to look less like their more inland counterparts, with branches curving away from the shore.

NPS Photo

To learn more about the iconic Live Oak tree, visit our pages on the history and natural significance of the tree at Gulf Islands.

NPS Photo

Southern Magnolia

Scientific Name: Magnolia grandifloraNatchez Trace Parkway

Of the many species of trees along the 444-mile stretch known as the Natchez Trace Parkway, one tree has become a symbol of Southern culture—the southern magnolia. Southern Magnolias are known for their beautiful cream-white flowers and large waxy leaves the size of dinner plates. This lovely tree can be found throughout the coastal plains of the South, from Eastern North Carolina to Eastern Texas. It is even the state tree of Mississippi—where you can find 309 miles of the Parkway! In 1829, President Andrew Jackson moved a southern magnolia from his home near Nashville, Tennessee—at the Northern Terminus of the Parkway—to the White House grounds, where it has lived for close to 200 years!

For more information about our tree visit Natchez Trace Parkway.

NPS Photo

Sweet Gum Tree

Scientific Name: Liquidambar styraciflua

Hamilton Grange National Memorial

In Hamilton Heights, New York City, on the grounds of Hamilton Grange National Memorial are several sweet gum trees. While Harlem is known as a metropolitan area today, it was the countryside in the early-19th century. In 1801, Alexander Hamilton commissioned architect John McComb Jr. to design a federal style country home in Upper Manhattan. Hamilton’s over 30-acre estate included many features such as a stream, garden, and thirteen sweet gum trees. The sweet gum trees symbolized the thirteen original colonies. New York City has a great climate for sweet gum trees, which were common features in the early-19th century Harlem area as they thrived near swamps and springs.

NPS Photo

Hamilton’s home, The Grange, was physically moved twice over the years. In 1889, it was moved to make room for the extension of the Manhattan Street Grid and in 2008, the National Park Service hired contractors to move the historic structure to St. Nicolas Park. Hamilton’s original sweet gum were not transported along with the home and no longer exist. However, park volunteers assisted in planting new trees in tribute to Hamilton and his country home.

Learn more about sweet gum trees at Hamilton Grange.

Photo Credit: Kat Kirby

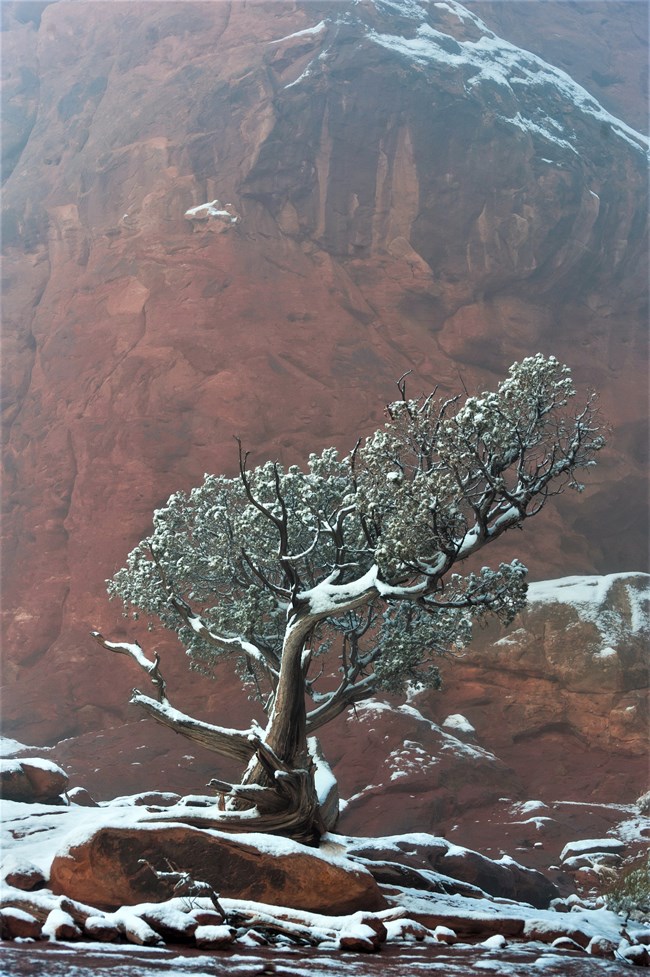

Utah Juniper

Scientific Name: Juniperus osteosperma

Arches National Park

Arches National Park is one of many homes for Utah junipers. These trees typically grow next to another tree, the Pinyon, and dominate dry, rocky landscapes with elevations between 4,500 and 6,500 feet. To increase their chances of survival during periods of drought, a Utah junipers’ twisted and gnarled branches can be cut off from the main supply of fluids, killing off the limb for the sake of the tree. Their haggard look and incredible adaptations make it the quintessential desert tree.

NPS Photo/Neal Herbert

Temperatures over the last 150 years have dramatically increased in Arches and across the southwestern United States. Precipitation patterns are also changing; some areas are wetter, others are drier, and rains are occurring at different times of the year. Native species cannot adapt quickly enough to these changes. Some plants are weakening and succumbing to drought, like pinyons and junipers—other species may die out entirely.

For more information about junipers at Arches, visit our trees and shrubs page.

Western Red Cedar

Scientific Name: Thuja plicata

North Cascades National Park

North Cascades National Park Service Complex has around 30 species of trees—one of the highest of any park!

NPS Photo

From the ponderosa pine on the dry southeast side of the Cascades, to the ancient western red cedar that reign over the wet lowland forests, and beyond to the wind-blown white bark pine hugging the tree lines of the highest elevations, North Cascades hosts an incredible diversity of trees and plants.

Cascade Mountain range creates a distinct boundary between the wet, western side of the park and the dry eastern side. Out of these and distinct ecosystems the red cedar is one of the tallest with heights reaching over 200 ft!

Visit our website to learn more about trees and shrubs at North Cascades.

Tags

- adams national historical park

- arches national park

- big thicket national preserve

- dinosaur national monument

- fort vancouver national historic site

- grand canyon national park

- great basin national park

- gulf islands national seashore

- hamilton grange national memorial

- john day fossil beds national monument

- longfellow house washington's headquarters national historic site

- natchez trace parkway

- north cascades national park

- redwood national and state parks

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- sitka national historical park

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore

- sunset crater volcano national monument

- iconic trees

- tree

- ecosystem

- nature

- flora

- witness trees

- juniperus osteosperma

- liquidambar styraciflua

- pinus ponderosa

- quercus garryana

- thuja occidentalis

- pinus palustris

- sequoiadendron giganteum

- metasequoia