Last updated: March 16, 2023

Article

Hamilton's Sweet Gum Trees

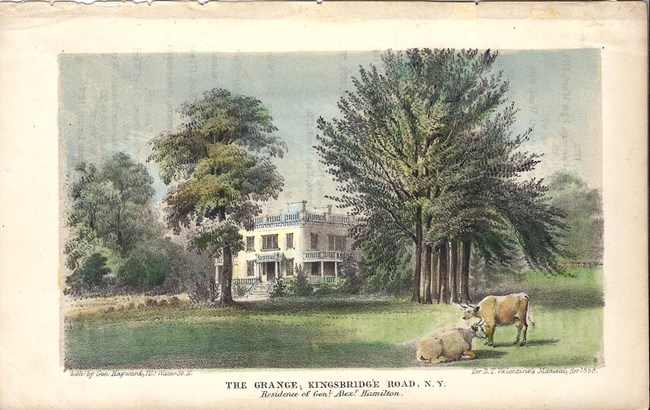

Since the earliest recorded memories of The Grange, a cluster of thirteen sweet gum trees has been associated with the house. Until 1889, the window of the study looked out upon these trees. In early illustrations of The Grange, and later, photographs, the sweet gum grove is an easily identifiable landmark, just steps from the front door of The Grange.

1858 George Hayward

To Be Cut Down or To Be Saved?

The origin of the thirteen trees has long been the subject of debate in local newspapers. While no letters or references by Hamilton survive about the trees, it has been a long-held tradition that they were planted by Hamilton. The earliest written reference to the trees appears in an 1872 edition of Appleton’s Journal, in which the trees are described as having been planted by Hamilton himself, and are said to represent each of the original thirteen colonies. The star-shaped leaves, it was noted, were particularly favorable to represent the colonies.In the late 1880’s, the general vicinity of The Grange was being developed within the Manhattan street grid; nearby lots were subdivided, row houses constructed, and roads were paved. Destruction seemed imminent for The Grange, until the house was moved several hundred feet away on Convent Avenue. Although the house was moved, the thirteen trees remained in their original location.

For the next 19 years, various individuals and organizations within the city either promoted the preservation of the trees, or called into question their authenticity.

Dubious Identity

In March of 1982, among a fierce debate for the use of land at The Grange’s old location, New York City citizen William Wood called the origin of the trees into question. In response to a recent philanthropic land purchase by O.B. Potter, Wood describes how he had entered into conversation with Alexander Hamilton’s son, John C. Hamilton, who informed him, “I am sorry to tell you that those trees were not planted by my father; they were there when he bought the place.” William Wood continued, “We sincerely hope that Mr. Potter’s usually keen judgement of the value of New York real estate was not disturbed in the bidding by the rush of patriotic associations connected with the trees that ‘were there when he bought the place’”.Nonetheless, public declarations and calls to action for the preservation of the trees continued. An April of 1892 article in the Illustrated American notes, “In order to protect the trees from the attacks of relic hunters, they are being guarded, day and night, by police and private watchmen.”

Although the claim of lime tree identity was corrected by a Columbia University professor within a year of the letter’s publication, the origin of the trees was thrown into deeper questioning. Amidst vocal public support for the trees, those in opposition continued to doubt their validity as patriotic icons. “But why,” wrote one anonymous critic, “he should have selected a species [from Mount Vernon] which already flourished in the vicinity of the Grange is, to say the least, surprising.”

For every critic of the trees, there was also a defender. However, by 1902, the trees were described in a New York Times article as “sad remnants”—only three trees in the cluster remained alive. “It is not likely that they will remain standing for any great length of time.”

Today’s Trees

On May 2nd, 1908, the article “Hamilton’s Last Gum Tree” appeared in the New York Times. “The last of the famous thirteen trees stationed by Alexander Hamilton to guard his home … departed this life May 1, 1908,” it was written. “The deceased has been a resident of the Heights for over a century, being the oldest inhabitant of his neighborhood.”At last, the thirteen gum trees which stirred so much emotion in the people of the neighborhood were gone.

NPS Photo

Sources:

“Hamilton’s Trees.” New York Times. July 2, 1889.

“The ‘Hamilton’ Trees.” New York Times. March 24, 1892.

Earle, Ferdinand P. “Hamilton’s Thirteen Trees.” New York Times. January 14, 1897.

E.R.D. “Alexander Hamilton’s Trees.” New York Times. December 3, 1899.

Crane. F.W., “New York Historic Trees.” New York Times. May 4, 1902.

Place, Frank. “Hamilton’s Last Gum Tree.” New York Times. May 4, 1908.

“Hamilton’s Thirteen Trees.” The illustrated American. April 23, 1892.

“Hamilton Grange.” Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science and Art. October 19, 1872.

“Hamilton’s Trees.” New York Times. July 2, 1889.

“The ‘Hamilton’ Trees.” New York Times. March 24, 1892.

Earle, Ferdinand P. “Hamilton’s Thirteen Trees.” New York Times. January 14, 1897.

E.R.D. “Alexander Hamilton’s Trees.” New York Times. December 3, 1899.

Crane. F.W., “New York Historic Trees.” New York Times. May 4, 1902.

Place, Frank. “Hamilton’s Last Gum Tree.” New York Times. May 4, 1908.

“Hamilton’s Thirteen Trees.” The illustrated American. April 23, 1892.

“Hamilton Grange.” Appletons’ Journal of Literature, Science and Art. October 19, 1872.