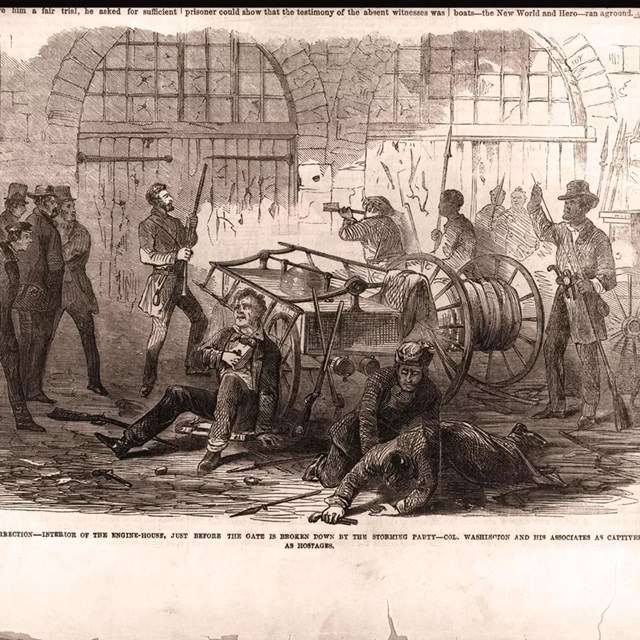

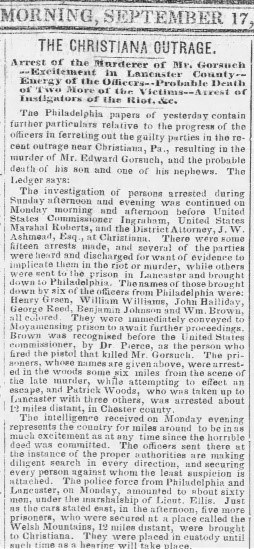

NPS The Road to WarIn the early 1850s, discussions among the Ridgely family, neighbors and guests in the mansion’s drawing room likely revolved around subjects such as the Compromise of 1850, “property” rights of enslavers, the role of abolitionists and free Black people, fears of uprisings by enslaved individuals, and the growth of sectionalism (exaggerated devotion to the interests of a specific region over those of the entire country).

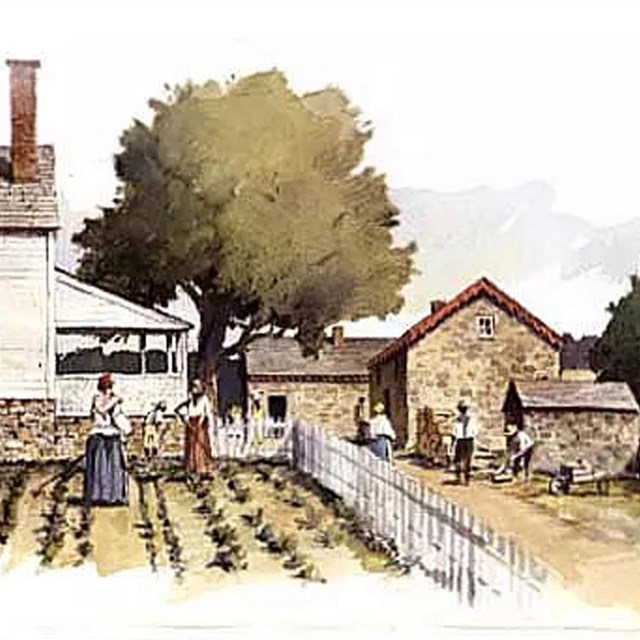

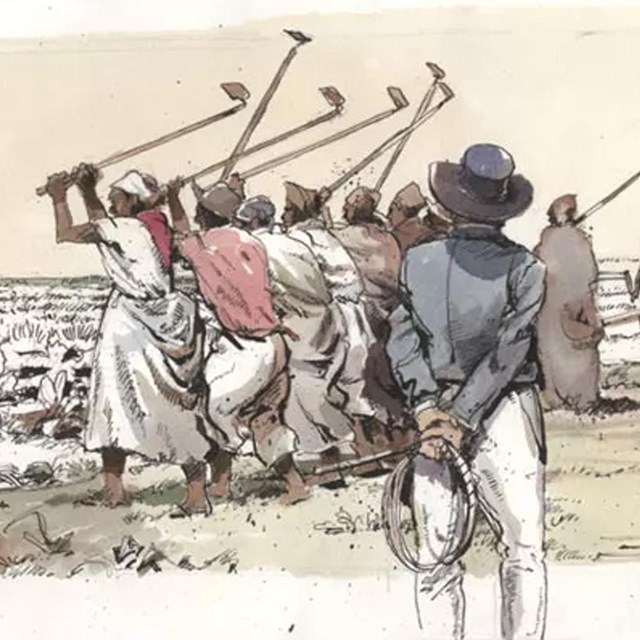

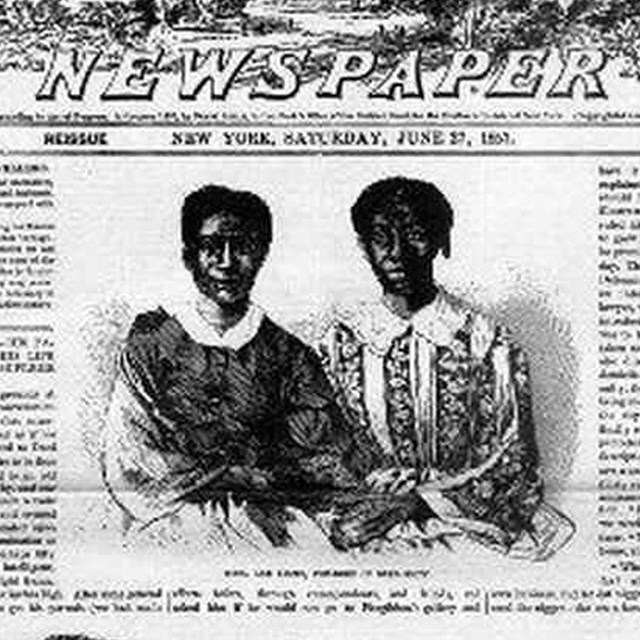

NPS Wartime HamptonOn the eve of the Civil War, the Hampton plantation covered over 4,000 acres and included over 60 enslaved people and a few free Black laborers. “I have many memories of the Civil War,” John and Eliza Ridgely’s grandson Henry White recalled, “the greater part of them not very pleasant to one, who, even as a child, greatly disliked heated discussions between members of the family and friends.” During the course of the war, family members reported that they were torn between sympathy for the Confederacy, hinging on their continued embrace of chattel slavery, and the fact that, in the words of White, the family maintained a “material interest dependent of Northern victory.” “Hardly a day passed,” he bitterly remembered, “that I did not hear one or more such discussions, during which the parties thereto frequently lost their tempers and ended…by not speaking to each other.” The Ridgelys feared that “Maryland would be a buffer state between the contending sections,” to say nothing of “the dread of confiscation and possible slave insurrection and rapine and murder.” War’s EndThe Civil War proved to be a defining moment in Hampton’s history. Although the three major military campaigns that came through the state of Maryland never reached Hampton, the battle fought on the plantation was one of culture, morality, and human rights. On multiple occasions large groups of enslaved people left Hampton during the war, attempting to seek their freedom. On January 1, 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation. Not only did the proclamation establish freedom for the enslaved African Americans living in Confederate states, but it also cemented this freedom by verifying their ability to serve in the United States military. On May 22, 1863, the War Department issued General Order No. 143 to establish a procedure for receiving African Americans into the armed forces. The order created the Bureau of Colored Troops. Some of those enslaved at Hampton who successfully were able to seek their freedom went on to serve in the United States military helping ensure not only their own freedom but also fighting for the freedom of others. One example is that of Franklin Johnson, a free Black servant at Hampton. In the spring of 1864, he enlisted as a soldier in the U.S. Colored Troops (39th US Colored Infantry). Tragically, Franklin Johnson died in September that year, after serving during this regiment’s very active role during the Overland Campaign and leaving his wife and children still enslaved at Hampton. In contrast, Charles Ridgely felt restrictions of freedoms with the suspension of Habeas Corpus in the state, being forced to be on house arrest, or face time in prison for his support of the Confederacy. In November of 1864 (just about five months before the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox) Maryland issued its emancipation of all enslaved people in the state with its new constitution. For Hampton their labor force was freed, but many had to make the difficult choice to remain as free paid laborers. By the end of the Civil War, there were 175 USCT regiments, containing 178,000 soldiers, approximately 10% of the Union Army. The mortality rate for these units was exceedingly high. One of every five Black soldiers in the conflict died, a 35% higher rate than other troops. On the day that Lee surrendered at Appomattox Court House, Virginia, on April 9, 1865, there were more African American soldiers fighting for the United States than the total of all Confederate forces. After the Civil WarFreedom brought its own challenges, since the formerly enslaved had few assets and little or no education. To survive, some drew upon the skills learned during their years of enslavement. By the last quarter of the 19th century, the neighborhoods of East Towson and Sandy Bottom on York Road grew as segregated communities for Black residents. Several freed people from Hampton settled in these two communities, where they helped establish institutions that served the needs of the people and provided social stability during a period of restrictive and discriminatory state and local laws.

Technological advances in the years after the Civil War, along with the loss of forced enslaved labor, led to fundamental changes for plantation economies such as Hampton. The invention of steam powered equipment meant that fewer people were needed to farm the same amount of land, but farm jobs also paid far less than factory work in Baltimore City. By 1888, a shortage of agricultural labor across Maryland led the state to recommend that farmers break up large tracts of land and sell them to white migrants from other states, who they believed would “work them properly.” These kinds of discriminatory practices contributed to the economic difficulties faced by African Americans who remained in rural areas. The shift from forced labor to paid labor and the technological advances caused a major change in the operations of Hampton, which would lead to the eventual economic decline of the estate. Individuals

Slavery at Hampton

More about Civil War

|

Last updated: June 23, 2025