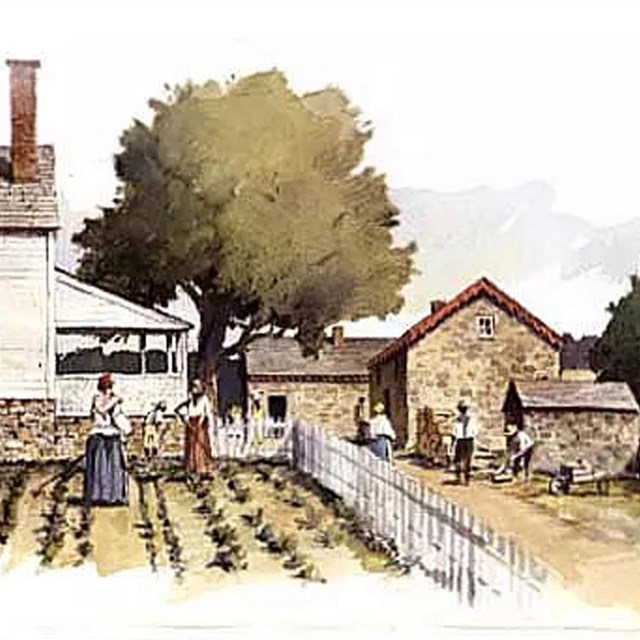

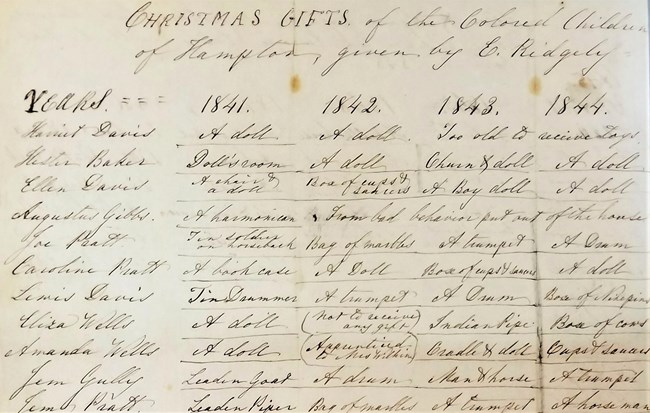

NPS Legislative bodies in colonial America, Maryland, and the United States passed laws to delineate terms of enslavement and to make self-emancipation significantly more difficult. During the holidays, the drawing room in the Hampton mansion is set up as it might have been for the presentation of Christmas presents for enslaved children. Hampton NHS archival records preserve a Christmas gift list for the enslaved children from 1841-1854, recorded by John and Eliza Ridgely’s daughter Eliza (“Didy”). The gift list records over 50 names of enslaved children over a decade and the corresponding gifts that were given including items like dolls, doll furniture, musical instruments, and toy soldiers. Although appearing at first to be a beneficial and kind gesture, this practice of gift giving also created a sense of obligation on the part of children. It was also used as a punishment; the list records that certain children did not receive a gift because of their behavior or even if the child attempted to seek their freedom. The list gives hints of other parts of the story as well, such as where young children from Hampton were rented out to other plantations (and thus not available to receive their gifts) or in some cases, who had successfully sought their freedom, never to appear on the gift list again. For example, after Rebecca Posey sought her freedom in the summer of 1852, she is noted as “gone” on the gift list that December.

Look at this example of a letter from Walter Bowie to Charles Carnan Ridgely dated February 20, 1796:

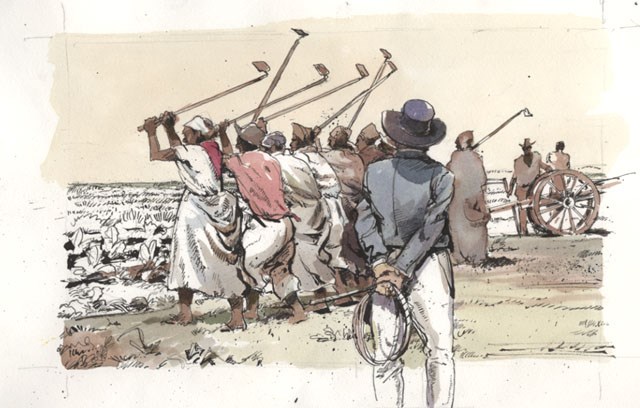

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center OverseersOver the decades, the Ridgelys relied on a mixed labor force of enslaved workers, convict laborers,indentured servants, hirelings, paid artisans, free Black laborers, and tenant farmers to maintain their estate. Indentured servants would have been used for labor in the early history of the plantation, as the system was phased out by 1800. As crews of workers at the Iron Furnace grew larger, white men were the managers and overseers who imposed strict work expectations in exchange for housing, supplies, a portion of the agricultural harvest and sometimes cash. White supervisors were hired consistently at the ironworks by the 1760s. In the early 1800s, several white managers were hand selected and trained by Charles Carnan Ridgely. These young men were chosen through the Baltimore Orphans’ Court as apprentices whom Carnan Ridgely molded as future managers. Samuel Reynolds was one of these young men; he contracted in 1804 to serve Ridgely for four years “to learn the Arts, Trades, and Mysteries of Managing an Iron Works or Furnace.” Within a decade, Carnan Ridgely had recruited a second young apprentice named Richard Green to manage the “mysteries” of Northampton. Carnan Ridgely also hired white overseers to manage large agricultural farms at the Hampton Home Farm, Epsom, Mine Bank, Reister’s Place and White Marsh. There was one Black overseer on the plantation, Savee in 1745, oversaw small, interdependent groups of enslaved people and indentured servants. In the early 20th century, the Black manager at the Home Farm, John Humphries, oversaw farm laborers, assigned chores, supervised the valuable dairy herd and other livestock among numerous responsibilities. Over the years, overseers used physical torture such as whipping and a variety of forms of cruelty to extract labor of hundreds of enslaved people. As with enslaved people, indentured servants were also subject to beatings and whippings. Additionally, those who attempted to seek their freedom could be put in iron collars. Inflicting physical torture could be a collaborative effort between overseers and enslavers.

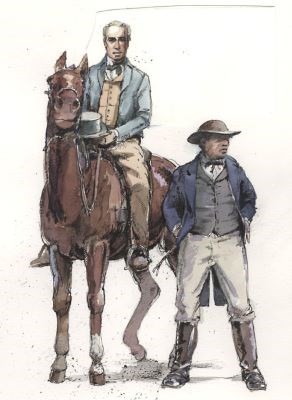

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center EnslaversJames McHenry Howard, Margaretta Howard Ridgely’s half-brother, recorded in his memoir family stories and oral histories told to him of treatment of the enslaved people at Hampton. In one incident, he records a day when “General Ridgely” (Charles Carnan Ridgely) had an overseer deliver ten lashes to an enslaved man. Despite the pain of these lashes, the man showed pride and refused to apologize, causing a dismayed and angered Ridgely ordered the overseer to dispense yet another ten lashes. In a battle of wills, the enslaved man remained “sullen and defiant” and refused to apologize. Charles Carnan Ridgely ordered ten more lashes with the angry admonition, “confound you why can’t you look pleased?” According to historian Kent Lancaster, “Once a slave owner wrote to ask if he might send his slaves to Hampton to be trained, which suggests, at least, that Ridgely discipline was exemplary to one white owner.”

Henry White (1840-1927), John Ridgely’s grandson, recalled that slavery at Hampton “was also bad for the tempers of the owners.” On several occasions, White recalled that “I well remember having seen my grandfather Ridgely lose his temper on one or two occasions, and box the ears of one of the grooms for reasons which seemed to me entirely inadequate.” White recoiled from these acts because they “left a most disagreeable impression on my mind, which is as vivid at the age of 75 as it was on the day of its occurrence (sic).” On the other hand, White’s memoir tells us that white children at Hampton considered enslaved individuals as “personal friends of the children of the house, the older ones being called ‘uncle’ and ‘aunt.’” Such a divided narrative conveyed both the horrors of slavery and, at the same time, a close-knit familial intimacy with the enslaved that characterized the paternalism of the Ridgely family as an enslaving class. Learn More

|

Last updated: June 18, 2025