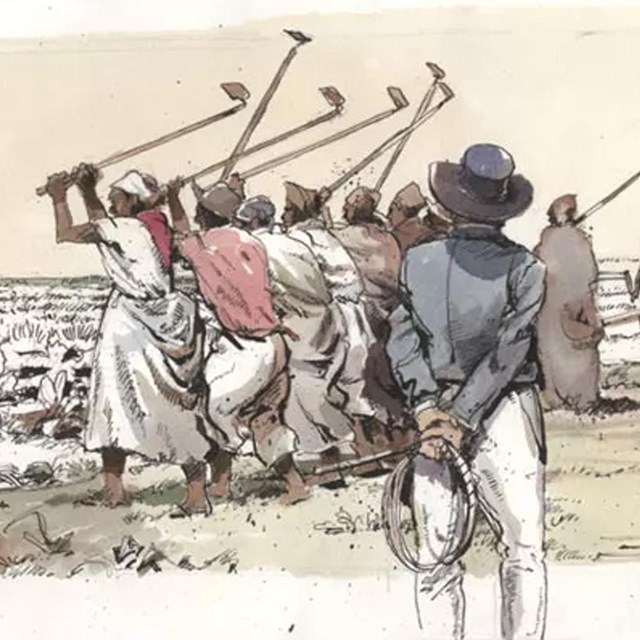

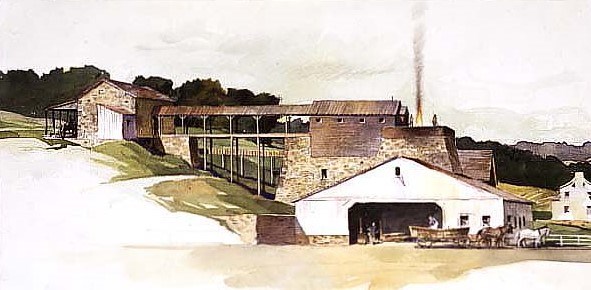

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center Hundreds of individuals were enslaved on this land, making Hampton one of the largest plantations in Maryland. Comparatively, three quarters of enslavers nationwide enslaved fewer than 10 individuals. In 1745, Charles Ridgely purchased 1,500 acres of land in northern Baltimore County. and opened the Northampton Ironworks in 1761. This purchase evolved to become the Hampton Plantation, which at its height was 25,000 acres. It would be passed down to seven generations of Ridgely descendants. Chattel slavery was present from the start of Hampton planation and persisted until Maryland in 1864. During this time, the Ridgely family enslaved over 500 people. After the Revolutionary War, British loyalists lost their lands and laborers. Charles Ridgely used the opportunity to purchase confiscated property. He increased his landholding to 24,000 acres and the number of people enslaved at Hampton to over 300 by the time of his death in 1790. Enslaved people labored at Hampton and Northampton as industrial, agricultural, and domestic laborers. Every aspect of life at Hampton included slavery. Enslaved people were not willing laborers, and the working conditions at Northampton Furnace was grueling and dangerous. The enslaved people were critical to the ironmaking process. Tasks included extracting iron ore and coal, mining and burning limestone, felling and cutting acres of timber, making charcoal and hauling fuel, iron ore, and finished products to and from the site.

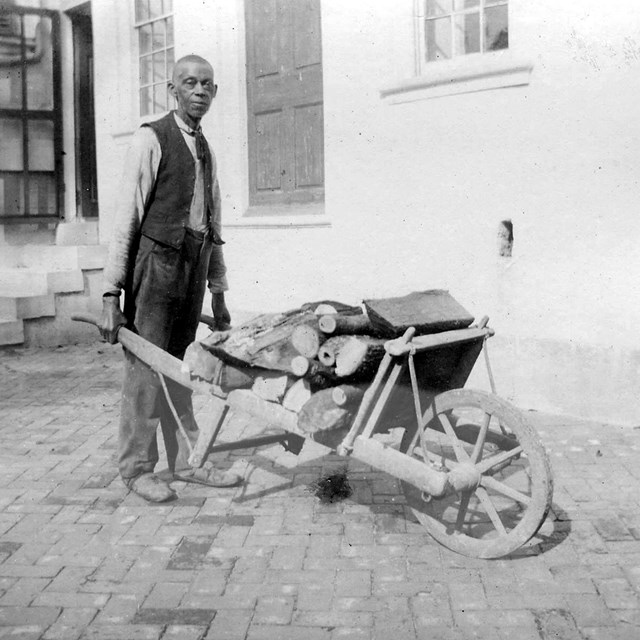

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center From the colonial period through 1864, the Ridgelys enslaved over 500 people. Enslaved people, from young children to the elderly, labored at Hampton and Northampton, as ironworkers, founders, limestone and marble quarriers, millers, blacksmiths, gardeners, dairymaids, jockeys, cobblers, seamstresses, woodcutters, field hands, carriage drivers, cooks, childcare providers, cleaners, builders and even overseers in the early days of the ironworks. All these positions combined to create a community within the plantation in which enslaved people held meetings, lived together, and practiced their religion while simultaneously being subject to cruel forms of control from enslavers and overseers. Refuge for freedom seekers was much closer for enslaved people at Hampton than for the enslaved in the Deep South. More than 80 people sought freedom from Hampton. Hampton’s close proximity to the “free state” of Pennsylvania led many enslaved people to seek refuge there. Others went to Baltimore Town, which had the largest number of Free Black residents in the US. The free community, the railroad, the Underground Railroad, and the shipping industry created opportunities for people fleeing bondage. Though not without exception, men traveling alone were most likely to be successful in their attempts to find freedom. People seeking freedom took in many considerations before taking the risk. Recapture might result in various forms of torture from overseers and enslavers to deter future attempts. Some decided to resist slavery in other ways, including working slow, breaking tools, and feigning sickness or injury.

NPS/Harpers Ferry Center A codicil (edit/addition to a will) to Charles Carnan Ridgely’s will in 1829 resulted in one of the largest manumissions of enslaved individuals in Maryland’s history. The codicil stipulated that woman under the age of 25 and men under the age of 28 remained enslaved until they reached those ages. Children under 3 years old were freed if a parent was also freed, otherwise, they remained enslaved. Maryland also banned the manumission of enslaved people over the age of 45. Those children, young adults, and older adults were bequeathed to the Charles Carnan Ridgely’s eight heirs. His oldest surviving son, John Ridgely, inherited the mansion and a portion of the plantation but without any enslaved people. Many freed people faced difficult choices as a result of the age restrictions. Many families were split as a result of the gradual manumission because one of their family members would remain enslaved. Some newly freed people left, but others sought to remain near their family. The new head of the Hampton plantation, John Ridgely, chose to continue the family’s cruel tradition of enslavement by purchasing and enslaving an additional sixty human beings. One of the many people John enslaved was a 17-year-old girl named Harriet Hawkins, who John sexually assaulted in the mid-1820s, when he was about 34 years old. This assault resulted in the birth of John’s enslaved son, Charles Hale Brown. The only person John Ridgely freed was his son, Charles Hale Brown, in 1846. Charles’ father continued to enslave his mother, Harriet Hawkins, half-brother, Nelson Hawkins, and three sisters. Nelson Hawkins successfully sought freedom in 1863, and Harriet Hawkins was emancipated in 1864 along with all those enslaved in Maryland. Researchers have a difficult task when it comes to the lives of enslaved people due to the lack of first-person accounts, although documentation recorded by the Ridgelys is extensive. The 2014 Hampton NHS Historic Resource Study, based on both important documentary research in the 1990s and new investigations, expanded the National Park Service’s understanding of the lived experiences of indentured servants and enslaved people. More recently, a three-year Ethnographic Overview and Assessment for Hampton NHS from 2017-2020 focused on establishing the connections of enslaved families in Hampton’s enslaved community: finding more about their lives and families in slavery and beyond and discovering living descendants. Primary sources including archives, probate and public records, research documents, oral histories and site visits have provided important discoveries in this ongoing work.

NPS This scrap of paper shows the division among Charles Carnan Ridgely’s heirs of the enslaved people who were not manumitted in 1829. Many of the very young children were separated from their families. Records show there were 130 enslaved people on the farms and at the ironworks in 1783; by 1829 there were nearly 350. Although this number dropped to 61 by the eve of the Civil War in 1860, the Ridgelys were still the second largest enslavers in Baltimore County. By the time of Emancipation in 1864, this number had dwindled to about 47, as a result of several individuals seeking their freedom during the American Civil War. Learn more

|

Last updated: June 18, 2025