|

Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, churches, city planning, campuses, fairs, and the many, many park designs.

Olmsted Archives Summit County Metropolitan Park Board (Summit County, OH)In 1921, renowned landscape architect and former Olmsted firm employee Warren H. Manning was employed by F.A. Seiberling, cofounder of Goodyear Tire, to design the gardens for his estate. Manning, who by now had formed his own practice but kept a close relationship with Olmsted Brothers, brought the young architect Harold S. Wagner to assist.Four years later, F.A. Seiberling was named a Summit County Parks Commissioner, with Wagner becoming the park district’s first director and secretary. Olmsted Brothers were hired to create a plan for the proposed park system for Summit County, and the areas recommended for preservation, which they submitted in September 1925. The main challenge Olmsted Brothers faced was choosing which places among the many beautiful areas they saw in Summit County to include in their recommendations for a park system. While Seiberling wanted Frederick Law Olmsted Jr to come out to Ohio, there were other projects that took precedence. Nonetheless, Olmsted assigned two of his finest landscape architects to the project — W.B. Marquis and E.C. Whiting.

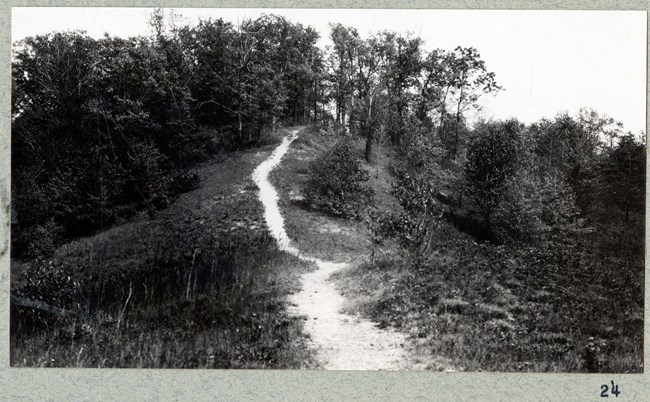

Olmsted Archives Wright Brothers Hill (Dayton, OH)Olmsted Brothers were hired in 1938 to assist in the design of Wright Brothers Hill. The hillside in the middle of the site, along with vegetation along the edges, separated the formal, symmetrical design at the top of the hill from the casual character of the lower area’s meadow. This subtle design technique keeps with the Olmstedian belief that potentially conflicting uses should be separated.According to Olmsted Brothers’ original plans, an eight-foot path was to encircle the entire site. A grass pathway once encircled the site, but no longer exists due to the loss of shrubs that defined the path’s edge. Wright Brothers Hill exhibits several characteristics of Olmsted’s design philosophies and practices. The diverse planting design combined with 100 different plant species at Wright Brothers Hill reflects the emphasis Olmsted placed on the liberal use of planting as a fundamental component of landscape design. A 1939 stock list specifies 8,181 plants for the site. Expansive lawns throughout the site, a large open meadow in the eastern portion of the site, and the dense tree and shrub plantings along the periphery and in specific other locations both define the spatial organization of the site and frame vistas into the larger landscape beyond. The site’s balance of formal and informal areas follows Olmsted’s idea that “formal design was generally limited to…special gathering areas.” Today, the site retains its original Olmsted Brothers plan.

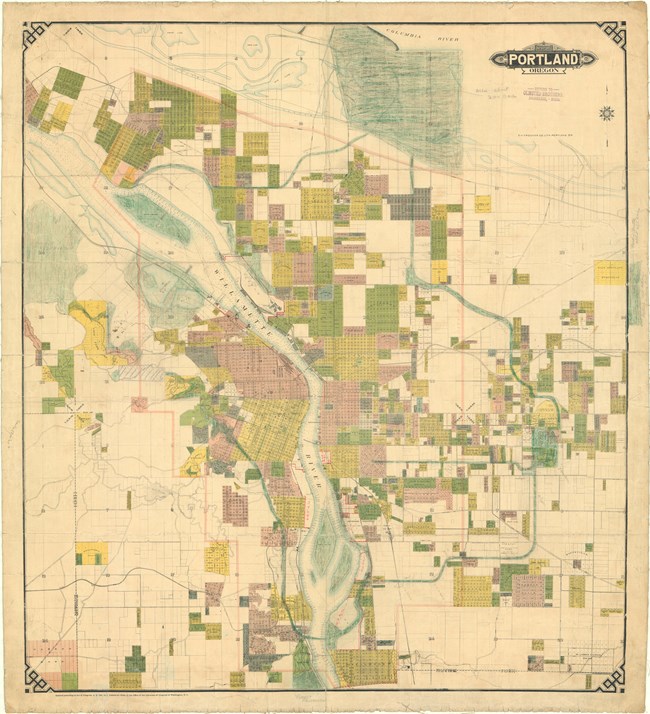

Olmsted Archives Terwilliger Boulevard (Portland, OR)When John Charles Olmsted laid out his plan to the Portland Park Commissioners in 1903, he planned for three parkways to connect the city, though only one was constructed: Terwilliger Boulevard. After James Terwilliger, one of Portland’s first permanent residents, passed away, his family deeded land that they specified to be used as a boulevard or parkway for the public. This allowed John Charles not only to provide for the community, but to preserve and protect the wooded character of the site, and its unobstructed views.Although John Charles sketched for Terwilliger Boulevard, it was completed under the Portland Park Superintendent Emanuel Tillman Mische, who, as a member of Olmsted Brothers, worked with John Charles on several Northwest designs. It was John Charles who recommended Mische for the position. Today, Terwilliger Boulevard retains much of its original design. Those traveling through are offered varied natural experiences that include panoramic views to both the city and mountains, immersion into a forest, passive park areas, turf areas, a playground, and forest trails.

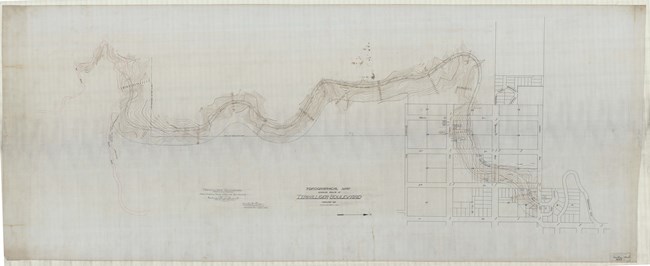

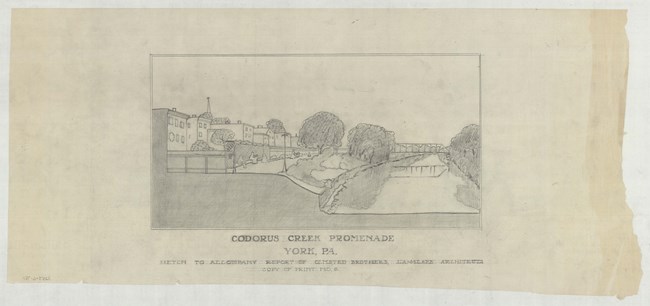

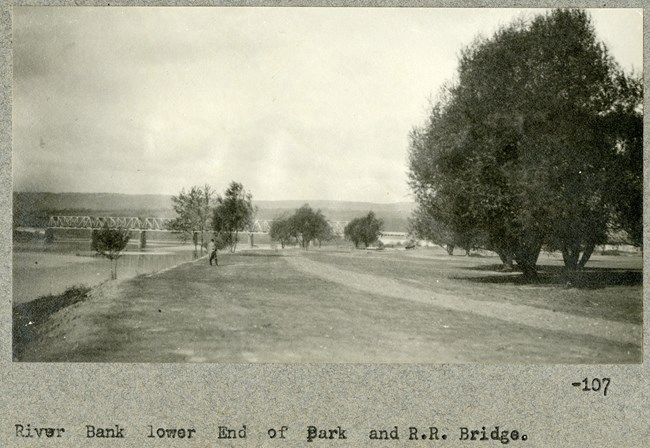

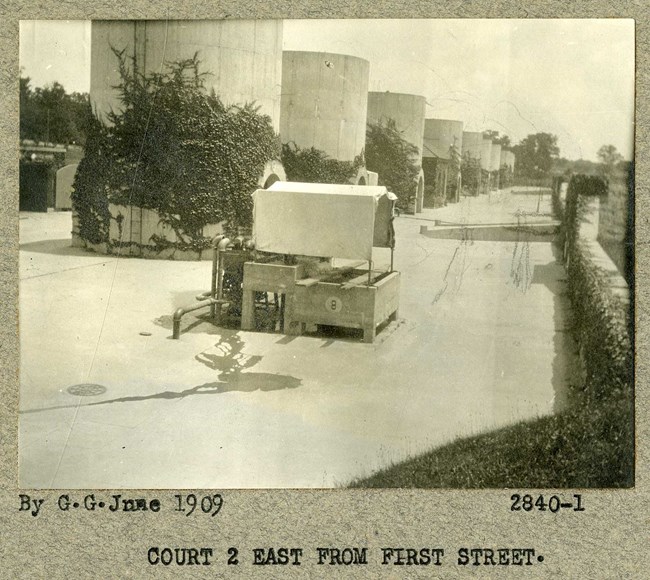

Olmsted Archives Codorus Creek (York, PA)In 1907, community leaders in York, Pennsylvania wanted to create a linear park, and knew they wanted to hire the best landscape architecture firm to do the work. The York Municipal League raised the required funds, and League secretary R.Z. Hartzler visited Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. at his Brookline office to ask him to look at park possibilities, as well as other needed improvements, such as a sewer system and paved streets.Olmsted’s fee for York was $600, almost $20,000 today. Olmsted arrived in York on April 10th, 1907, meeting with League members and taking a tour of the city. Olmsted believed sewage treatment should be top priority, though he was also pleased with the potential park sites. Looking at Codorus Creek, Olmsted wanted his design to be able to handle the area's frequent floods. Olmsted had been told by a local that ““not too many years ago, the Codorus was a pretty natural park with boating,” and if the sewage was handled, flooding addressed, and boundaries of the Codorus were wide enough on the banks to keep people from dumping, and erecting buildings, boating could once again return. Even though the rail trail has made the Codorus embankment walkable, it still is far from the “water park” that Olmsted envisioned.

Olmsted Archives Kirby Park (Wilkes-Barre, PA)The combination of a considerable donation of acreage on the west side of the Susquehanna River, combined with a monetary gift from local businessman Frank Kirby, prompted Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania to contact Olmsted Brothers to design a 106-acre park. After the 1921 death of John Charles Olmsted, the year the park was commissioned, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. would take over and finish the park, which took over three years to complete.From the outset, frequent flooding was a major concern for the site. Olmsted recognized the effect a flood might have on the land and designed two plans for Kirby Park, one to be implemented if a levee were built before the park, and one if the park was built first. Olmsted Jr. was determined to develop an uninterrupted, pleasant rural and sylvan scenery for his successful country park. As development occurred, an additional donation from Kirby allowed Wilkes-Barre to acquire an additional one hundred acres, expanding the park’s land. Miantonomi Memorial Park (Newport, RI)The grounds that would become Miantonomi Memorial Park were used as picnic grounds throughout the nineteenth century, until 1881 when Anson Stokes purchased it for farmland. After Stokes’s passing in 1913, his wife Helen inherited the property. Around that time, the Newport Improvement Association commissioned Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. to prepare a plan for overall improvements for the city. Within Olmsted’s Newport Plan, he urged the city to acquire Stokes’s property for a park.Olmsted submitted his plan to Newark in January of 1921. It included a main gated park entrance and a drive leading from the main entrance to a second, gated entrance. Also included in Olmsted’s plan was parking spaces, playing fields, and a small children’s playground in a regraded lawn area.

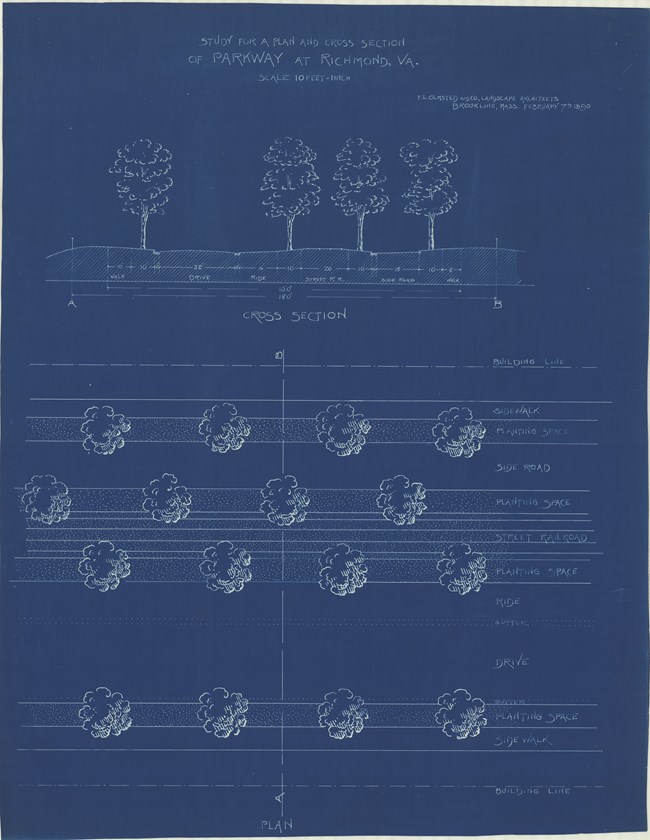

Olmsted Archives Brookland Parkway (Richmond, VA)In 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted was commissioned to create a plan for Sherwood Park, a new streetcar subdivision for Richmond, Virginia. Of his plans for the community, only Brookland Parkway was realized. Originally named Brookland Park Boulevard, Olmsted planned it as the spine for the Richmond suburb, flowing diagonally through the city grid, creating a scenic centerpiece for the neighborhood.Olmsted’s earliest plans for Brookland Parkway included a broad, tree-lined parkway with irregular curves that would be large enough to accommodate a central median for streetcars that wouldn’t disrupt horse-drawn carriage traffic. In the end, the streetcars were never implemented, and the horse-drawn carriage roads would be transformed for vehicular traffic.

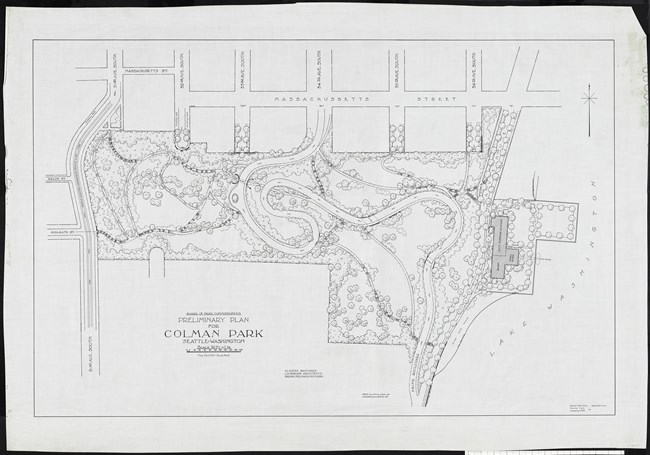

Olmsted Archives Colman Park (Seattle, WA)Colman Park is located within a steeply sloped area that John Charles Olmsted referred to as the Rainier Heights Landslide Section in his 1903 Seattle Parks Report. In that report, John Charles proposed acquiring the entire length of steep slope for park purposes, warning against using the land for subdivision development because “Houses will probably continue to be moved gradually on to adjoining land owned by someone else, and there will be no end to the trouble, expense and inconvenience due to the continuation of the slide if it is allowed to become occupied by houses… On the other hand, the movement of the land would be of small consequence if the ground is turned into a public park.”Additionally, Olmsted proposed a parkway that would run along the top of Colman Park’s slope, providing views to Lake Washington and the mountains further in the distance. Due to the ambitiousness of the plan, the parkway was never realized. However, some parcels within the area that would have been the parkway were either donated or purchased for parkland for Seattle. Within Colman Park, four bridges allow pedestrians to move, removed from vehicular traffic. Located at the North edge of the Mount Baker neighborhood, the forested hillside park features paths, community gardens, forests and lawns. Colman Park epitomizes John Charles’ goal: “to secure and preserve for the use of the people as much as possible of these advantages of water and mountain views and of woodlands.”

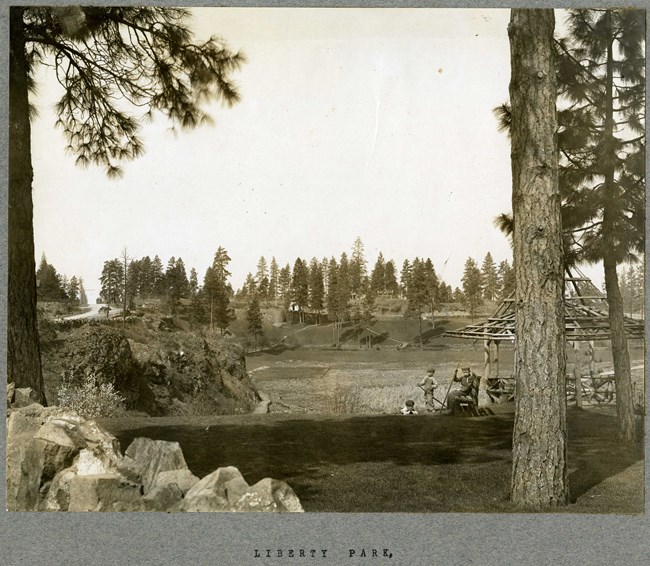

Olmsted Archives Liberty Park (Spokane, WA)Olmsted Brothers were hired to design three parks in Spokane, Washington, with John Charles Olmsted taking the lead. When John Charles and firm member James Frederick Dawson first visited the site that would become Liberty Park, they were thoroughly impressed with the area’s hills, valleys, and basalt outcroppings.After viewing the land, John Charles thought it was unsuited for development, but would be the ideal location for a park. Liberty Park was developed under John Charles’ recommendations, with structures like an arbored terrace and a promenade. Liberty Park was meant to fit into its surroundings, and in 1908, the plan for Liberty Park was approved and construction began. Unfortunately, Liberty Park would be changed forever in 1968 when Washington State placed I-90 directly through the heart of Liberty Park. The Interstate took nearly 19-acres of Liberty Park’s land, pond, and lakes. Construction on the interstate took at least two years, and once completed, one of Spokane’s prettiest parks envisioned by Olmsted Brothers was lost forever.

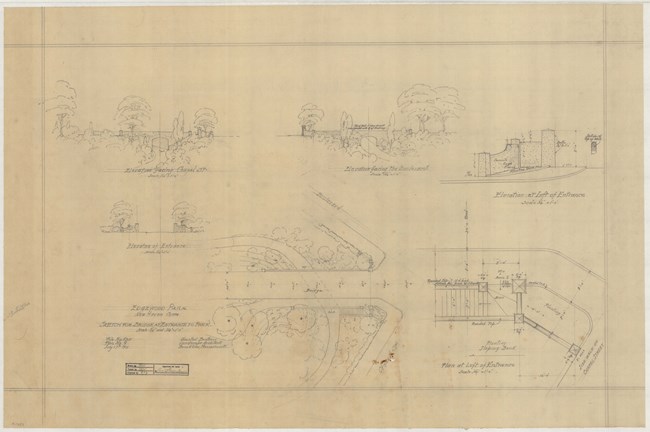

Olmsted Archives Jefferson Park (Seattle, WA)When John Charles Olmsted visited Seattle in 1903, he toured a 115-acre tract of land at the top of Beacon Hill, owned by the city. On a stump-studded open space, John Charles recommended clearing the level land and developing it into ball fields bordered by already existing trees and shrubs. Additionally, John Charles suggested adding two pleasure drives and a boulevard for vehicles and several walks, all branching off from a main circuit walk around the perimeter of the park for pedestrians.John Charles proposed that “at suitable places vistas between the plantations should be arranged to command the distant views of Lake Washington.” First known as Beacon Hill Park but later renamed Jefferson Park, was meant to be linked to other Seattle parks through boulevards. John Charles suggested Board of Park Commissioners build a drive from the far corner of Jefferson Park to Lake Washington Parkway. At Jefferson Park, John Charles’ preliminary 1912 plan included a golf course, ballfields, playgrounds, a running track, and shelter serving as an overlook. A walkway encircled the reservoirs and allowed pedestrian access to the views out over the city and the bay on the western and northern sides of the reservoirs.

Olmsted Archives Green Lake Boulevard (Seattle, WA)Seattle, Washington experienced both a population and economic boom in 1903, and to oversee park planning for the area, the City of Seattle hired Olmsted Brothers. As with many of the Olmsted Brothers projects in the Northwest, John Charles Olmsted took the lead on designing many of Seattle’s parks, like Green Lake Boulevard.Work on Green Lake began in 1908 by merging aesthetics with function. John Charles’ vision was to provide a sanctuary where residents could enjoy nature and partake in a peaceful moment away from the hustle and bustle of life. John Charles placed trees and shrubbery along the boulevard’s outer edge, many of which survive today. Additionally, John Charles included a graceful parkland meandering along the shores of Green Lake. By covering this area with grass, John Charles predicted that it would “be one of the most attractive places for crowds to ramble and sit under the trees.” John Charles also recommended “sufficient space be provided for field sports, and also for a formal garden.” An earlier movement stressing the importance of outdoor recreation for children prompted John Charles to include a playground in his plan.

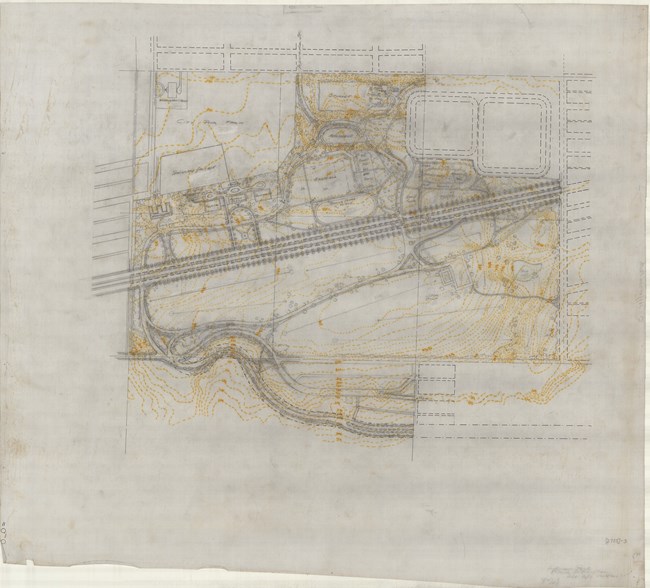

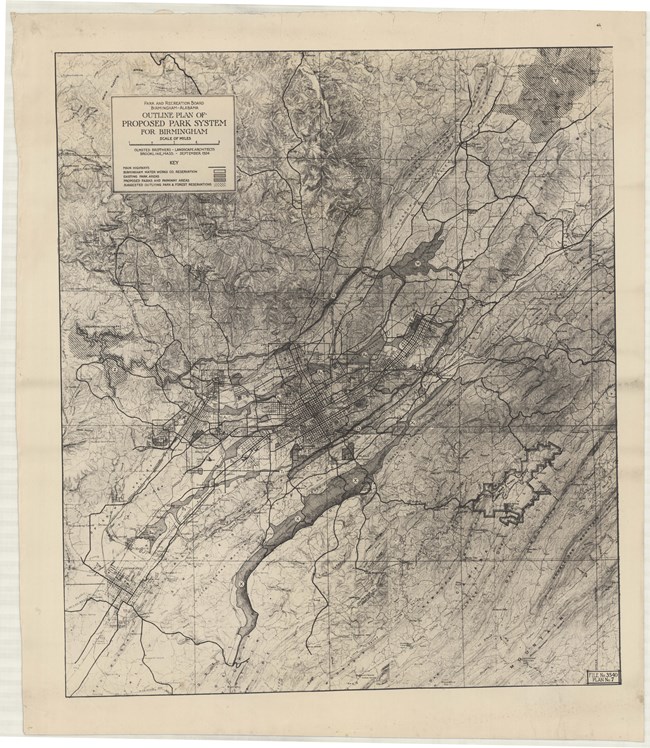

Olmsted Archives Birmingham Parks (Birmingham, AL)Birmingham, Alabama was quickly becoming one of the South’s largest industrial centers by the 1920s. Aware of the benefits a city gets from a park system, leaders of Birmingham sought to increase its 600 acres of parkland, and in 1923, the Birmingham Park and Recreation Board was formed. One year later, the Board contracted Olmsted Brothers to create a design.In 1925, Olmsted Brothers published their report proposing both active and passive neighborhood parks within walking distance of all residents, regardless of race or economic status. Leading work on the Birmingham Park System was Frederick Law Olmsted Jr, with Edward Whiting serving as project manager.

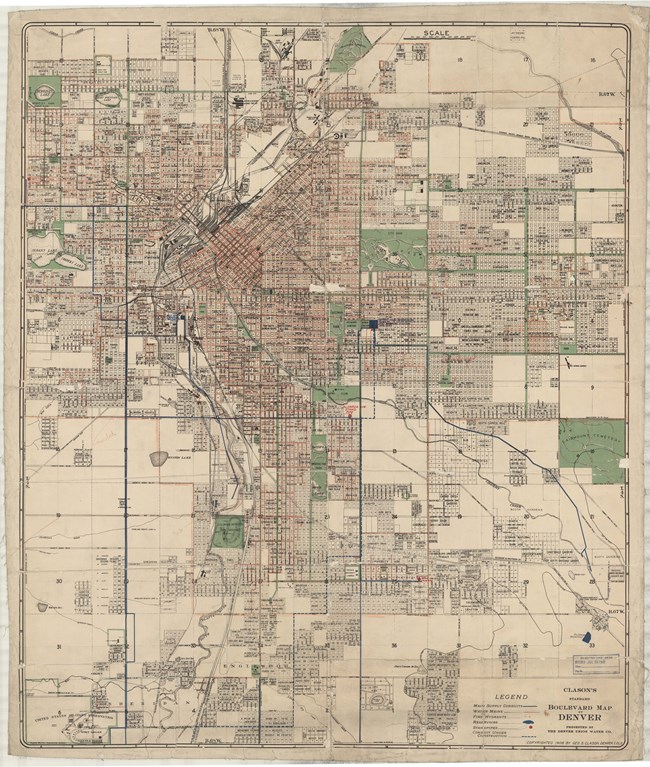

Olmsted Archives Denver Parks (Denver, CO)In December of 1911, representatives from three Denver civic groups came together, and invited Olmsted Brothers to help make their Rocky Mountain town more accessible to tourists and locals by creating a chain of parks, as well as well-built roads. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. accepted the commission and traveled to Denver to inspect the 250-square-miles of remote and mountainous landscape.In Olmsted Jr’s first report of 1912, he recommended acquiring large parcels of land to protect scenery, the construction of an interconnecting system of roadways, and the development of facilities for active and passive use. One year later, in his second report, he recommended the acquisition of 41,320 acres of land. Olmsted Jr. 's work on the Denver Parks was an early example of sensitive and scenic road building techniques that would soon be used all over the National Parks. In October of 1913, Olmsted Jr directed that “the smaller the extent of obviously artificial and manhandled surface, whether in the roadway or adjacent to it, the better it is for the mountain scenery.”

Olmsted Archives Beardsley Park (Bridgeport, RI)In 1881, wealthy cattle trader James Beardsley gifted 100 acres along the Pequonnock River in northeast Bridgeport, Connecticut to be designated as a public park. Frederick Law Olmsted and John Charles Olmsted assessed the scenic advantages of the large trees, hilltop views, boulder outcroppings, and sloping meadows of the site, and suggested that even more land should be donated.In their 1884 report, the two Olmsted’s suggested thinning woodlands into open glades for a parklike character, while also encouraging native shrub growth. Also suggested in the report was enhancing hillside areas for distant views while utilizing natural boulders to create a vine-covered courtyard for carriages. Aware that not everyone had a carriage, the plan for Beardsley Park included a railroad station for public access. Olmsted’s vision for Beardsley Park is remarkably similar to what you would see today, despite the transformation of many meadows into ball fields and other athletic facilities, as well as the addition of a zoo in 1922. Looking at Beardsley Park, the Olmsted’s believed that "It is just the place for a day's outing. It is a better picnic ground than any possessed by the city of New York after spending twenty million dollars for parks."

Olmsted Archives Portland Park System (Portland, OR)In 1903, the Portland Board of Park Commissioners decided to expand and link parks throughout the city, connecting them and providing Portland with their own lungs of the city. John Charles was already in Portland when the Board made their decision working on the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition when asked to develop a park system for Portland.John Charles developed an 18-pint plan for Parkland with various parks and boulevards, many taking advantage of the natural mountain scenery and nearby rivers. John Charles also proposed a scenic drive he called south Hillside Parkway, since renamed to Terwilliger Parkway, the only parkway from the plan fully realized. Five years after the decision to expand Portland’s parks were made, the city needed a park superintendent, so John Charles recommended his Olmsted Brothers colleague- Emanuel Mische. With John Charles serving as a visiting consultant, Mische continued the implementation of his plan. Today, Portland’s parks and parkways span 12,500 acres, with much of its land acquisitions following John Charles’ plan.

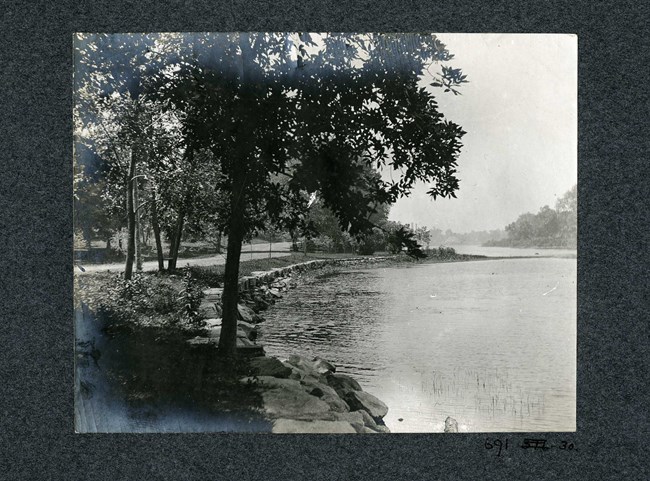

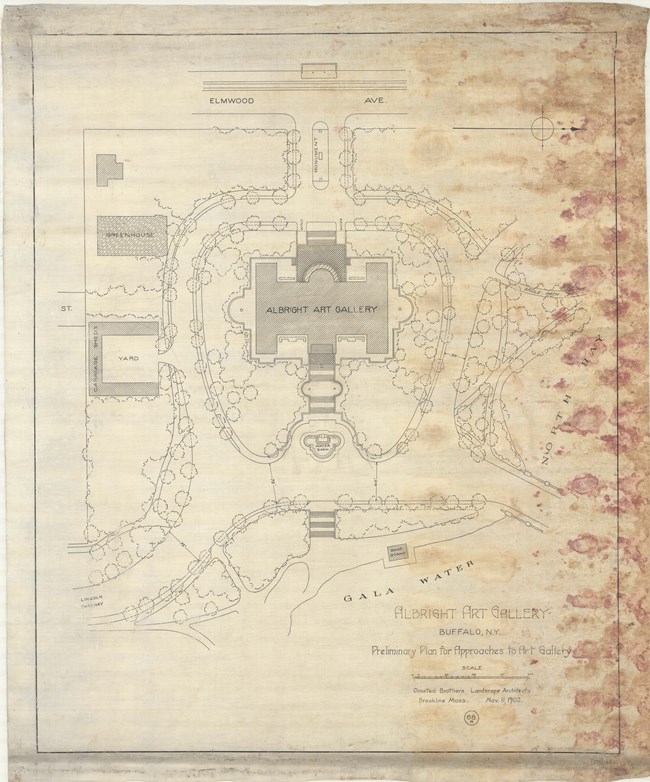

Olmsted Archives Delaware Park (Buffalo, NY)The centerpiece of Buffalo’s Park System, which Frederick Law Olmsted described as “the best planned city … in the United States, if not in the world”, Delaware Park is often just referred to as “The Park”. Designed by Olmsted, Vaux & Co. in 1868, it was the first opportunity Olmsted had to personally select the site to be used.Like many of Olmsted’s great parks, Delaware Park is split into three sections: a prominent water feature, a large meadow, and significant wooded areas. Construction would last from 1870 to 1874, and the 350-acre park was bordered by seven miles of footpaths, bridle paths and carriage drives. In 1886, Delaware Park was expanded by twelve acres, with Olmsted drawing up plans for the addition. Olmsted correctly predicted that Delaware Park was destined to have a “distinguished position among the parks of the world.”

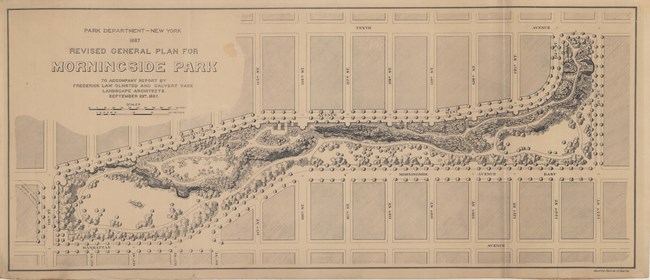

Olmsted Archives Morningside Park (New York City, NY)After having such a tumultuous relationship with Central Park’s Comptroller Andrew Haswell Green, it’s interesting that Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux would be so willing to work with Green again. However, differences were put aside to give New York City another park, though it wasn’t easy going.Andrew Haswell Green conceived the idea for Morningside Park in 1867, and four years later a plan proposal was submitted by New York Parks Engineer-in-Chief M.A. Kellogg, though it was rejected. In 1973, Olmsted and Vaux submitted their plan, but that was also rejected. Seven years later, architect Jacob Wrey Mould, who had also worked on Central Park, was hired to rework Olmsted and Vaux’s original plan. Fourteen years after their original proposal was rejected, and one year after Mould’s 1886 death, Olmsted and Vaux were once again hired to develop Morningside Park. Their second plan included expansive lawns, dense plantings of trees, and meandering paths- all meant to enhance the area’s natural beauty. Despite his death, even some of Mould’s designs were included, like the monumental entrance to Morningside Park. Old plans were also recycled in 1998 for the construction of the Kiel Arboretum, which was modeled on an 1858 Olmsted and Vaux design for Central Park that was never implemented.

Olmsted Archives Keney Park (Hartford, CT)In 1893, patriarch of one of Hartford’s most prominent families, Henry Keney, gifted 533 acres of land to the city, with the only requirement being the land be used as a park. Three years later, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot were hired to design Keney Park as part of their Hartford Park System. Opening in 1896, the Olmsted design didn’t truly take place until the 1920s.Keney Park would get an additional 160-acres in 1924 after the Keney Trustees transferred ownership to Hartford. Now Olmsted Brothers, John Charles Olmsted based his plan for Keney Park off Charles Eliot’s originals. They intended for the park to have a series of regional landscapes like meadows and forests. Firm associate Percival Gallagher was tasked with overseeing the construction of the park’s pastoral scenery, supervising the transportation of over half a million yards of earth, and planting native foliage. The varied spaces are linked by a meandering carriage drive and with three gates, the surrounding residential neighborhood benefits from Keney Park.

Olmsted Archives Hartford Parks (Hartford, CT)Seventeen years after the country’s first municipal park, Bushnell Park, was created, Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted began drafting plans for a system of parks connected through parkways. Olmsted’s 1870 planned would be designed in the picturesque style by himself, his sons John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., his firm partner Charles Eliot, and others.To accommodate the growing metropolitan area, parks dense with trees would provide a lush oasis and recreational facilities. Due to their father’s failing health, Olmsted Brothers acted as Hartford’s parks consultants from 1895 through to the 1940s. While Olmsted Sr. 's plan focused on passive parks, Olmsted Brothers focused on active neighborhood parks and playgrounds, most used by the nearby public schools. The Hartford Park System allows the Olmsted legacy to span several decades and generations. All three Olmsted’s worked on parks in Hartford, from the smaller squares and greens to large scale municipal parks, nothing was off limits in Hartford, a city who trusted their native son to do the best for them.

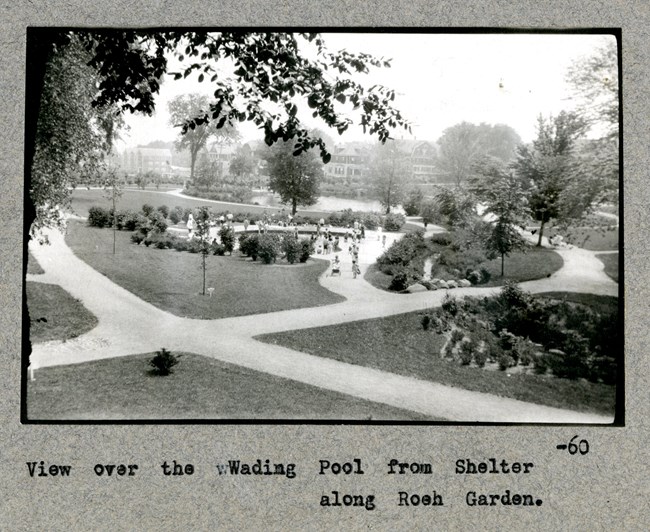

Olmsted Archives Goodwin Park (Hartford, CT)In 1870, Hartford native Frederick Law Olmsted began drafting a plan for a network connected parks for the city. While Olmsted worked on several Hartford parks, by 1895 his health had begun failing him, forcing him to cut back on work, pushing his sons and partners into more projects. As partners in Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot, John Charles Olmsted and Charles Eliot created their design for Goodwin Park, part of the Hartford Park System.Initially named South Park, it was renamed in 1900 to honor Hartford Park Commissioner Revered Francis Goodwin, a critical player in getting Hartford its parks. The 200-acre park consists of woodlands and meadows, with Great Meadow being its most prominent feature, a 90-acre, gently sloping lawn surrounded by native tree groves. Recreational elements like children’s play area, outdoor gymnasium, and a wading pool were placed along wooded edges, providing privacy. Despite the addition of a golf course and the park being used as an airfield throughout the 1920s and during WWII, Goodwin Park retains much of its original design. Now surrounded by residential neighborhoods, the park serves the community, providing mental and physical health benefits.

Olmsted Archives Edgewood Park (New Haven, CT)In 1910, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was tasked with designing Edgewood Park in New Haven, Connecticut. In his lengthy report that year to the Civic Planning Committee of New Haven, he wrote that “If the people of the city… are to have the benefit of a place where they may habitually get a little healthful recreation out of doors under agreeable and refreshing surroundings… if the children are to be able to make such use of a playground; if their elders are to get with tolerable frequency even a little walk in the park or square for air and for refreshment from the dulling routine of life in factory, store, office, and cramped dwelling house or flat; if the mothers are to get out occasionally to a pleasant park bench with their sewing or what not, while the children play about them: then facilities for this sort of recreation must be provided within easy walking distance of every home in the city. Any plan that deliberately stops short of such provision…. Is in so far illogical, unjust, undemocratic and unwise.”Olmsted Jr., as his father taught him, was committed to provide refuge and recreation away from city life. When Edgewood Avenue, with its busy traffic, began creeping too close to the park, Olmsted Jr. believed “its inharmonious character should be modified by properly planned grading and planting of its slopes.”

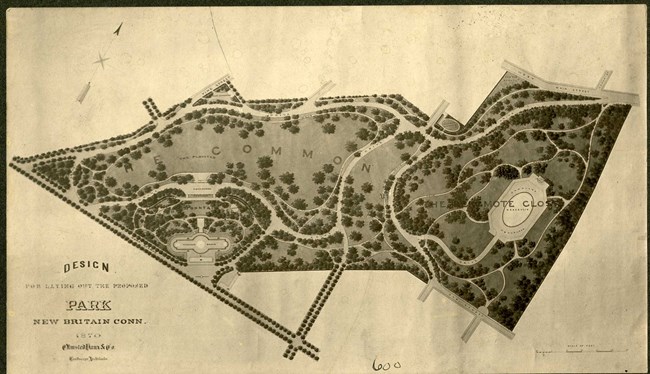

Olmsted Archives Walnut Hill Park (New Britain, CT)Olmsted, Vaux & Co. were hired by the New Britain Park Commission in 1870 to design a park on land the city had recently purchased from the Walnut Hill Company. Olmsted’s plan for Walnut Hill Park was broken up into Walnut Hill, where he intended for an overlook, and a meadow, referred to as the Common.Olmsted’s scenic overlook at the uppermost point of the park with a meandering path leading to it was never realized, and it is now the home of a 90-foot-tall obelisk built in 1930. The lower part of the park was designed as Olmsted intended, with the lower area being developed as a meadow with paths encircling the lawn.

Olmsted Archives Riverside Park (Hartford, CT)Building on their father’s plan for Hartford, Connecticut’s system of parks, Olmsted Brothers began work on Riverside Park in 1895. 75-acres along the Connecticut River were meant to provide recreational space for nearby residents. With the assistance of Percival Gallagher, John Charles Olmsted supervised the park’s design.Like many of their parks in Hartford and across the country, John Charles designed a picturesque landscape of open lawns surrounded by walking paths, overlooking the nearby river. At the center of the park sat Riverside Pond, with tree groves and native shrubs lining the riverbanks, helping to mitigate erosion. When the park opened in 1899 it followed Olmsted Brothers plan, however, over time the original plan degraded, and is no longer evident. A 24-acre subtraction of land has left Riverside Park nestled between a railroad and an interstate.

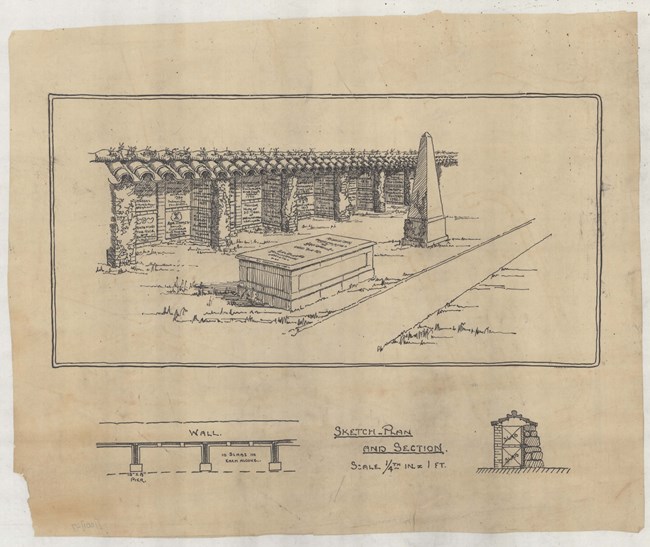

Olmsted Archives Memorial Park (New London, CT)In June of 1884, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired by a local from New London, Connecticut to design a park for the community. Olmsted’s concept for what would become Memorial Park emerges from his sketch studies. With the library sitting high on the site providing a commanding view of the city below, walking paths connect it to the area below. Olmsted wanted existing knolls and depressions excavated to accentuate grading changes and emphasize the upper lawn and terrace area.To connect paths, Olmsted planned for sequences of stairs, with low plants and vines covering the slope. On May 9th, 1885, Olmsted wrote to the New London Park Commission that “The outlook towards the Sound is not to be improved by producing superficially any suggestion of the 'natural' or existing conditions. (It would be very greatly improved by the purely artificial arrangements that have been suggested.) I can think of nothing better and nothing less costly to be done with the quarry district than to handle it as I have proposed, making a defile by excavating a considerable amount of rock; building the terraces so as to increase the effect of depth and abruptness or declivity in this defile; establishing pockets and making deposits of soil from which to grow vines and rock plants by which to tie the rock in place artificially to the rock set up, and soften the asperity, hardness, and coldness of the material, and by opening a convenient circuit of communication through the defile by which this otherwise intractable part of the property would be utilized and seem by contrast to give value to the other part in which there is a possibility of obtaining gracefulness of surface and more tranquility of character.”

Olmsted Archives McMillan Park (Washington, D.C.)Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was only 30 years old when Michigan Senator James McMillan asked him to join his Senate Park Commission, assisting in the development of the monumental core of Washington, D.C. Not only did Olmsted assist on the siting of buildings and roads, he also made recommendations for parks. To honor his commitment to D.C., McMillan Park was created and named in 1906 to honor the man so instrumental in shaping D.C.A result of the McMillan Plan and City Beautification Movement, McMillan Park was a collaboration between Olmsted Jr and architect Charles Platt. The 92-acre park was built as a water treatment plant, with only 25-acres being used for a leisure park. Winding through the park is a curved driveway and several walking paths, designed by Olmsted Jr.

Olmsted Archives National Zoo (Washington, D.C.)On the slopes of Rock Creek Park sits the 163-acre National Zoo, with Frederick Law Olmsted serving as the site’s landscape architect. Olmsted envisioned the zoo having a picturesque, park-like setting with a wide, gently curving path with rustic buildings nestled into the landscape. Using the flattest area to center the development, Olmsted believed the design should fit, as best it can, into a “consistent scheme for the future”.In 1892, Olmsted urged that "the hardy grazing animals particularly should have the most ample possible paddocks," with his early design calling for extensive pastures. Olmsted Sr.’s work was advanced by John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr in 1905. Today, Olmsted Walk in the National Zoo takes visitors through a historic pedestrian promenade, just as planned by Olmsted Brothers.

Olmsted Archives Lewis Fulton Memorial Park (Waterbury, CT)Located at the center of Waterbury, the 70-acre Fulton Park, designed by Olmsted Brothers, is a prime example of Olmsted design legacy. A picturesque park with rolling terrain and broad vistas, all framed by trees, Fulton Park is home to meadows punctuated by ponds and streams, woodlands filled with stone walls and hiking paths, lush gardens, and recreational facilities.It was William E. Fulton, President of the Waterbury Farrel Foundry and Machine Company, who in 1919, after acquiring land no longer being used by the city, contacted Olmsted Brothers to begin designing his park. Fulton Park embodies the democratic Olmsted approach to designing parks- provide an escape for city residents where they could nourish their physical, social, and emotional needs.

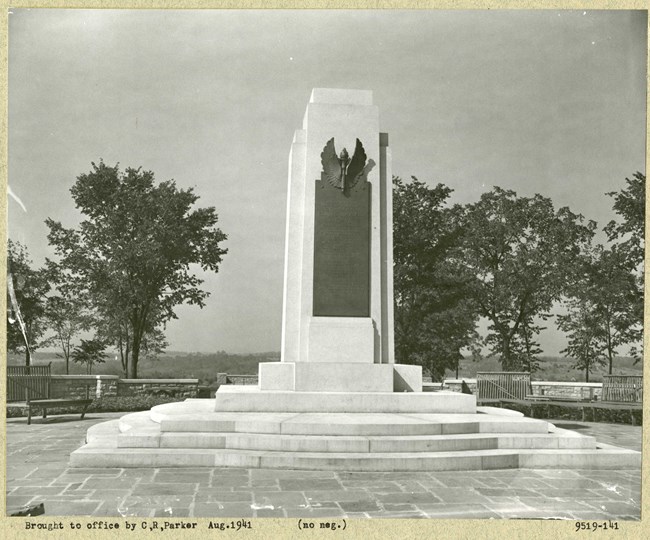

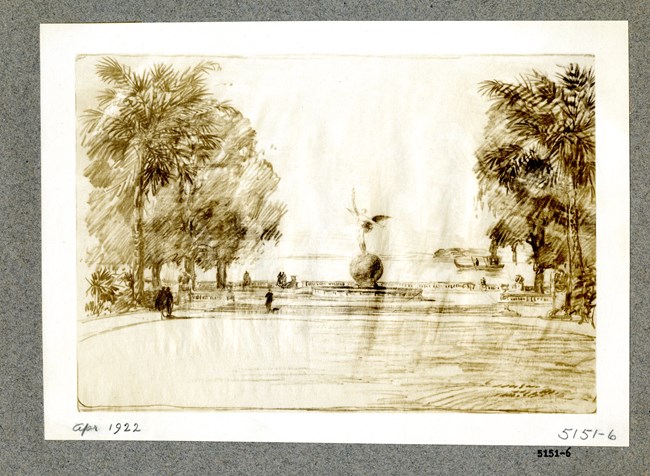

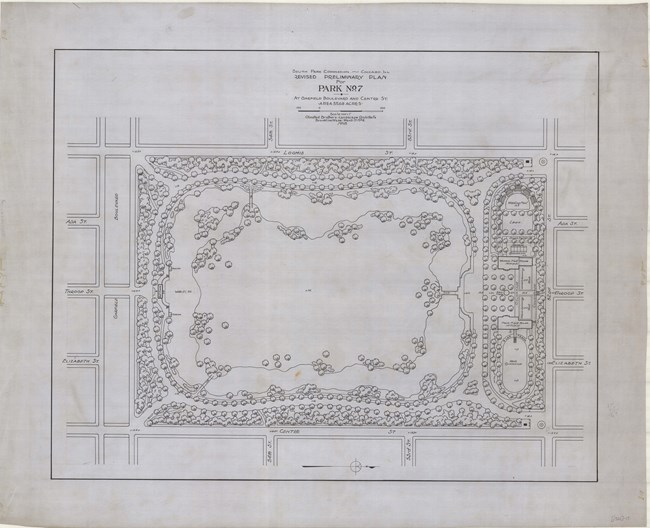

Olmsted Archives Memorial Park (Jacksonville, FL)Ninah M.H. Cummer, founder of the Jacksonville Garden Club, aspired to create a worthy civic gesture to commemorate Floridians who perished while fighting for America in WWI. With her own waterfront property as the site for the park, Cummer commissioned Olmsted Brothers to complete a landscape design.Olmsted Brothers’ design of 1922 included a large, central oval lawn with walkways around the park and along the ocean's edge. The focal point of the park, and the memorial to the fallen soldiers, is a bronze statue by C. Adrian Pillars, who depicted “the winged figure of youth.” Olmsted Brothers’ plan keeps Pillar’s memorial in mind, complimenting but not distracting from it.

Olmsted Archives L.P. Grant Park (Atlanta, GA)In 1883, Grant Park was established, and became Atlanta’s oldest park, when Colonel Lemuel P. Grant, a local successful engineer and businessman gifted the city 100 acres of parkland. Of Olmsted Brothers, John Charles Olmsted led this project, and in 1903 visited and drew up plants for Grant Park. During his visit to Grant Park, John Charles sketched and photographed the land, noting the high quality of homes in the area.Reacting to such densely planted oaks blocking views, John Charles proposed a natural planting scheme, carving out openings by thinning existing stands of trees and replacing them with diverse understory planting. In 1916, Atlanta City Council adopted John Charles’ master plan for Grant Park. After years of growing use and declining maintenance, a new Master Plan for Grant Park was created, all based on the original Olmsted Brothers plan.

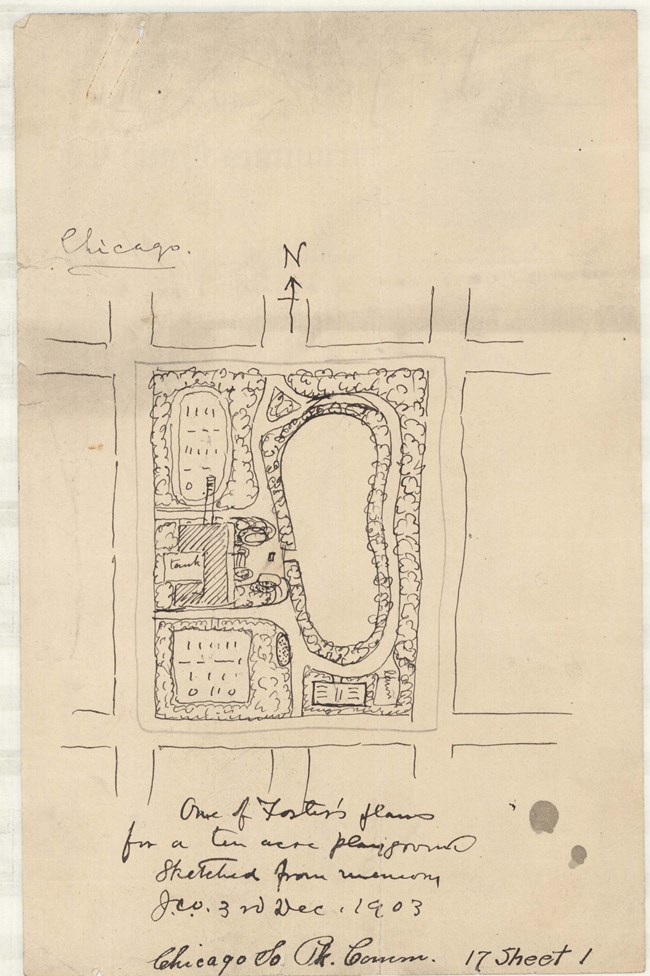

Olmsted Archives Sherman Park (Chicago, IL)Of the ten neighborhood parks designed by Olmsted Brothers in 1904 Chicago, Sherman Park is the largest clocking in at 60-acres. John Charles Olmsted led the design for Sherman Park, with the design’s most significant element being a closed-loop lagoon that parallels the park’s boundaries, covering about two-thirds of the parkland.From the picturesque lagoon, an island meadow was created with thinly planted trees enclosing the perimeter. Sherman Park was designed in a rectangular shape, with each of the four corners of the park containing a simple, neoclassical stone bridge for pedestrians, providing access to the island and connecting the drives that circle the park.

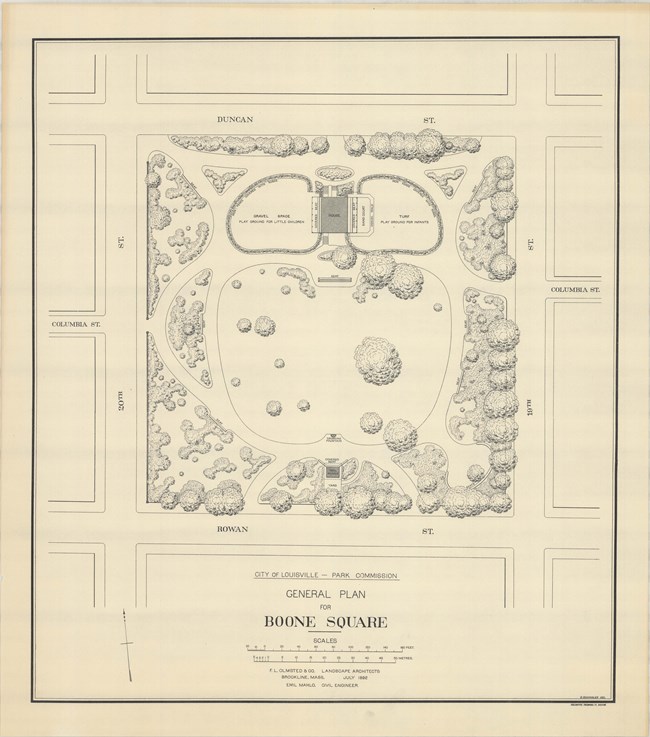

Olmsted Archives Boone Square (Louisville, KY)Frederick Law Olmsted’s design for the Louisville Park System, a network of parks and boulevards, was the last park system design Olmsted would create. One of the first of Louisville’s parks, Boone Square, is also one of the smallest in the city. Nestled in the Portland neighborhood, Boone Square only takes up one city block, about four acres.Due to its small size, Boone Square is truly a neighborhood park, with space for recreation, picnic areas, and shaded walks, all still largely in place today. By the 1930s, Boone Square had grown in popularity, with a wading pool and volleyball courts being added. After WWII, Boone Square was left alone until the 1970s, when the park was updated to include basketball courts, playgrounds, fountains, and a picnic shelter. Surrounding Boone Square is a low stone wall with entrances at each of the park’s four corners.

Olmsted Archives South Park Commission (Chicago, IL)One year after the 1869 creation of Chicago’s South Park Commission, tasked with overseeing the development of parks and boulevards along the southside of the Chicago River, Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux were hired to design a park system that would exceed one thousand acres. Always focusing on natural features, Chicago’s Park System was built around a series of water features and included promenades, gathering places, and gardens.Unfortunately, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871 would destroy Olmsted and Vaux’s drawings, along $5.4 billion dollars’ worth of damage. A new landscape architect, H.W.S. Cleveland, was hired after the fire to develop the Park system, with instructions to minimize any land alterations. Olmsted would have the opportunity to work on Chicago parks again during the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

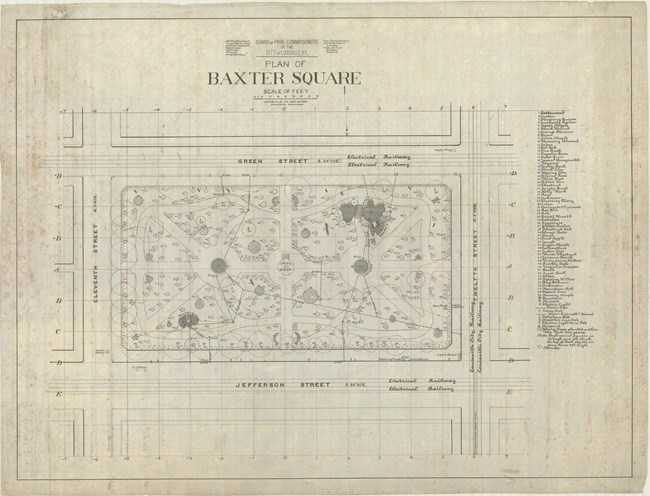

Olmsted Archives Baxter Square (Louisville, KY)Louisville, Kentucky’s first public park, Baxter Square, was created in 1880, one year before Frederick Law Olmsted would submit his plans for Louisville Parks and Parkways. The land was acquired by and named for John G. Baxter, Louisville’s mayor at the time. In 1887, a movement was started by prominent men of the area to develop three large suburban parks for Louisville.Olmsted was commissioned to design Baxter Square in 1891 though plans weren’t completed until 1901, well after Olmsted’s retirement. Olmsted Brothers took over at Baxter Square and proposed a planting plan to the city. Today, Baxter Square is still surrounded by its original stone wall and contains the original park shelter and mature vegetation. Looking at other Louisville parks, Baxter Square is a bit more formal, with simple, curved, shaded walkways with benches going around the perimeter.

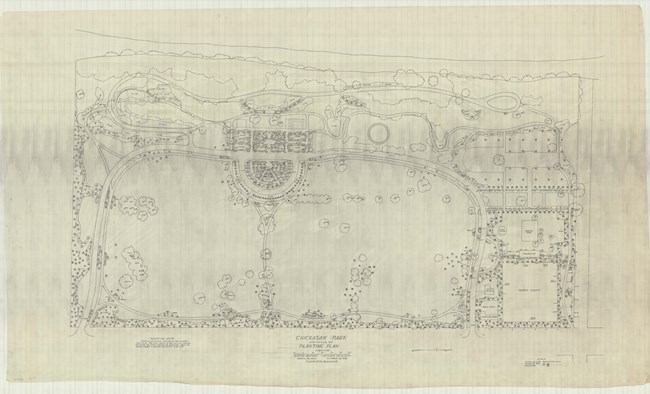

Olmsted Archives Chickasaw Park (Louisville, KY)Building off their father’s Louisville Parks and Parkways System, the Olmsted name would return to the area in 1923, when Olmsted Brothers were hired to design Chickasaw Park for the nearby neighborhoods. It is believed that Chickasaw Park was the only municipal park designed by the entire Olmsted firm, from 1883 to 1979, to serve African Americans during the time of segregation.Until Louisville Parks were desegregated in 1955, Chickasaw Park was the only park to offer recreational space and park amenities to the Black community in the area. At 61-acres, Chickasaw Park features a fishing pond, picnic areas, playgrounds, splash pad, pedestrian paths, and ballfields, offering both passive and active recreation. Throughout Chickasaw Park and the entirety of the Louisville Park system, red oak cypress and white pines dominate.

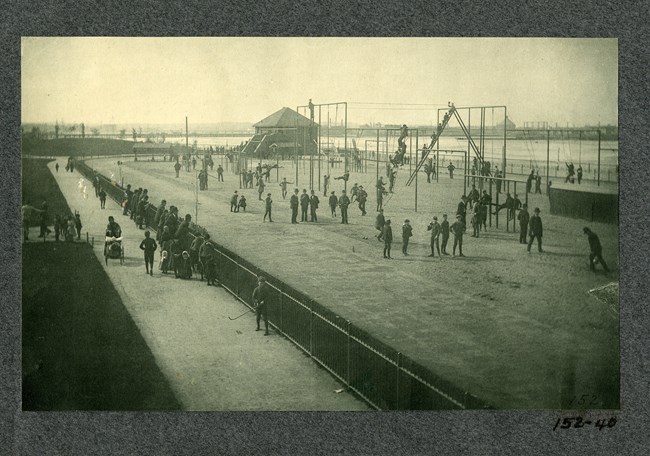

Olmsted Archives Charlesbank (Boston, MA)Located along Boston’s Esplanade, Charlesbank Park allowed Frederick Law Olmsted to design the first open air gymnasium and exercise facility of its kind in a public park. Olmsted’s move to Brookline in 1883 allowed him to design the park four years later. A waterside park, Charlesbank acted as the Beacon Street entrance to Olmsted’s Back Bay Fens.Working with fitness pioneer Dudley A. Sargent, Olmsted created a linear park with features like a promenade, boat landings, running track, trapezes, swinging rings, jumping and pole vaulting, shot putting, and more, separated by gender and age. Olmsted requested that Boston Park Commissioners provide equipment, maintenance, and instruction to the community, free of charge. While Olmsted supported facilities for exercise, he favored parks that encouraged individual sports, not team ones. That is why Charlesbank didn’t include a baseball diamond or football field. Opening in 1889, Olmsted’s original plan would get a redesign in 1910 after the construction of the dam, by Olmsted firm member Arthur Shurcliff. Due to increased vehicular traffic, most of Olmsted's design was removed in the 1930s.

Olmsted Archives Beaver Brook Reservation (Belmont, MA)After the 1893 establishment of the Metropolitan Parks System, pushed forward by Olmsted firm partner Charles Eliot, Beaver Brook Reservation was to become the first reservation in the system. Eliot, Frederick Law Olmsted, and Sylvester Baxter, who helped created the Metropolitan Parks System, all emphasized the importance of preserving the distinct natural scenery of the area.The Olmsted firm would design formal paths and trails through Beaver Brook Reservation well into the 1890s, as well as two footbridges across the Brook. Despite careful attention of both Olmsted firm members and park superintendents, many of the area’s distinctive trees succumbed to disease, weather, and old age within thirty years of the reservation being created.

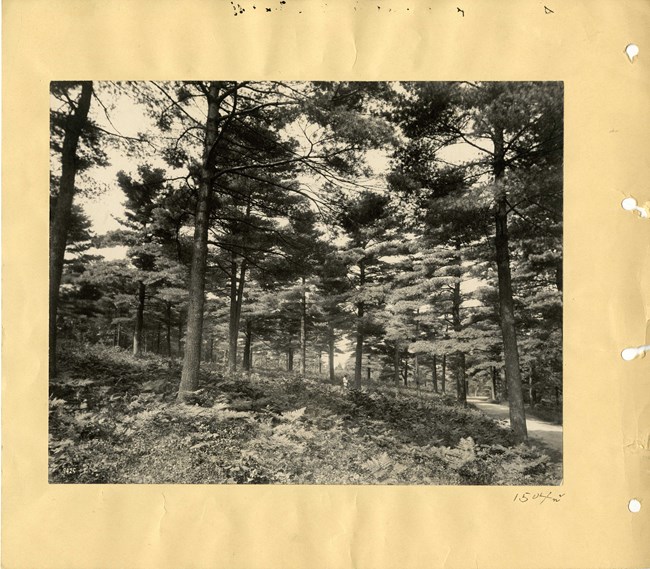

Olmsted Archives Blue Hills Reservation (Milton, MA)In 1893, Olmsted firm partner Charles Eliot and member Warren H. Manning created an interconnected series of parks in the Greater Boston Area that was known as the Metropolitan Parks System. That same year Eliot would acquire Blue Hills Reservation, believing the landscape's wildness would counter Boston’s intentionally manicured parks of the time, like the Public Garden.After the new Metropolitan Park Commission purchased the land, one Commissioner declared that “there will be no attempt made to beautify them. We shall not even own a lawn mower.” Eliot envisioned carriage riders enjoying the paths of Blue Hills, coming around corners to reveal scenic vistas. At 125 miles of trails, traversing forests, meadows, swamps, pond edges, and marshes, Eliot achieved his goal of “affording widespread panoramic prospects in all directions.” |

Last updated: June 15, 2024