Last updated: December 29, 2022

Article

Stratotype Inventory—John D. Rockefeller, Jr. National Memorial Parkway, Wyoming

NPS photo.

Introduction

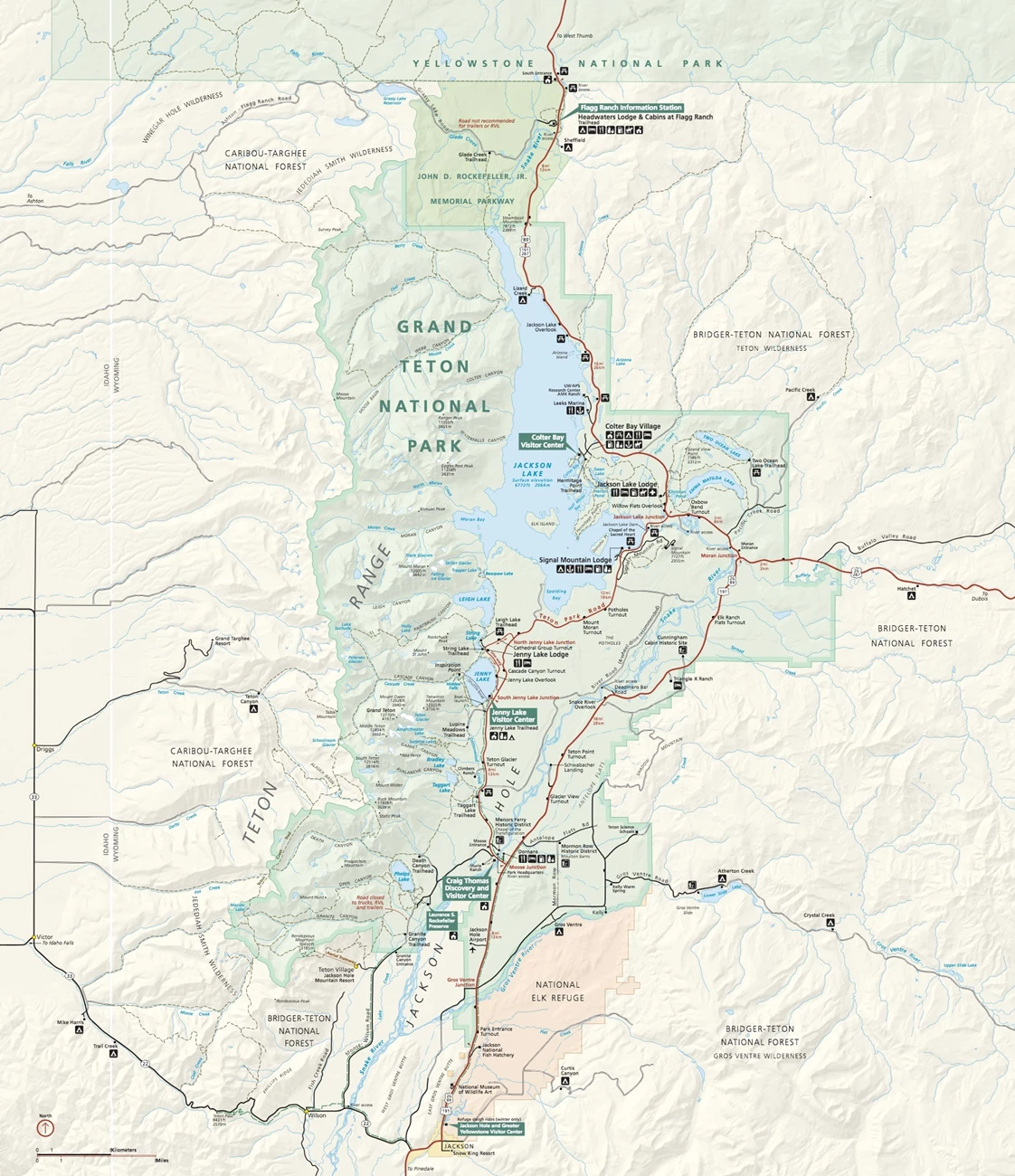

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. National Memorial Parkway (JODR), located in Teton County, Wyoming, was authorized by Congress on August 25, 1972 to commemorate Rockefeller’s philanthropy and significant contributions to the establishment of several national parks: GRTE, Acadia National Park (ACAD), Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GRSM), and Virgin Islands National Park (VIIS). Congress also named the highway from GRTE’s south boundary to West Thumb in YELL in honor of Rockefeller (Anderson 2017). The 132 km (81 mi) parkway encompasses 9,622 hectares (23,777 acres) of remote and largely uninhabited land that provides a natural link between GRTE and YELL (Figure 9).

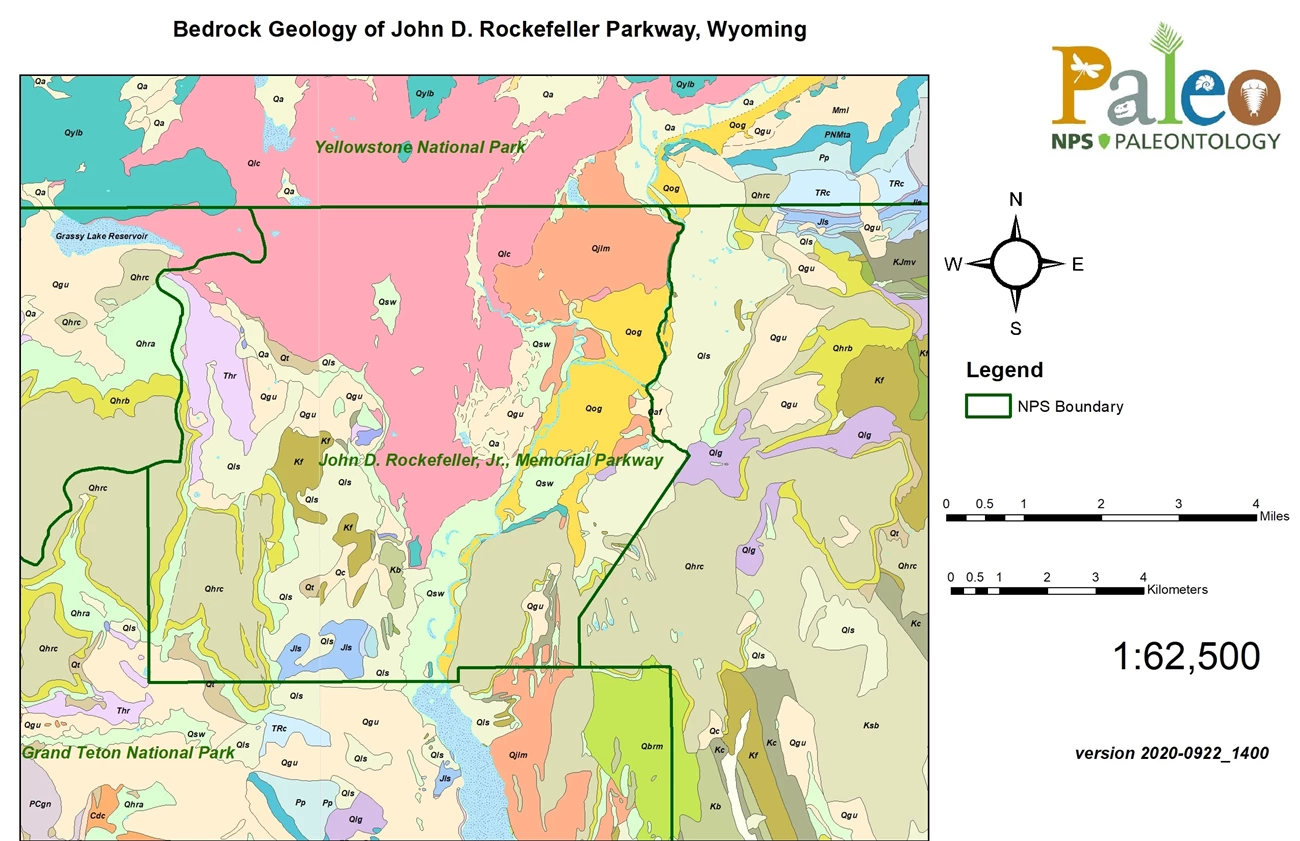

The parkway is a mountainous region with moderate to steep slopes situated between the volcanic plateaus of YELL and the jagged fault-block mountains of GRTE. The geology of the parkway largely reflects influences of extra-regional origin and contains geothermal, glacial, and volcanic features of particular interest (Figures 15 and 16; KellerLynn 2010). Jurassic and Cretaceous sandstone and shale are present, but more recent lava and ash from Yellowstone volcanism blanket much of the older Cretaceous bedrock. The most prominent volcanic event was the caldera eruption that created Yellowstone Lake 600,000 years ago, which deposited thick layers of rhyolite in the parkway (Rodman et al. 1992; KellerLynn 2010). The Teton fault, so significant for GRTE, has also uplifted the topography and influenced seismic activity within the parkway. Glaciers originating in YELL entirely covered the parkway during the Pleistocene Epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), creating its gouged valleys and rounded mountains (Rodman et al. 1992).

NPS image.

Significance and Geologic Resource Values

The Grand Teton National Park and John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway Foundation Document (2017) references the following fundamental resources and values identified for GRTE and JODR: “Geologic Features and Processes. Powerful ongoing geologic forces shape the park, parkway, and nearby Yellowstone National Park. Regional heat from the earth’s mantle combined with local heat from the plume of magma under Yellowstone have lifted and cracked the earth’s crust. Earthquakes generated along one of these cracks–the Teton fault–tilted the Teton Range skyward while dropping the valley of Jackson Hole. As the mountains were rising, massive glaciers flowed south from Yellowstone and alpine glaciers carved out U-shaped canyons and piedmont lakes ringed by glacial moraines. The glaciers melted, washing soil from the valley floor, and leaving behind an outwash plain covered with cobbles and carving terraces that step down to the modern Snake River. Today, small earthquakes occasionally shake the region, suggesting the power of future mountain-building. Remnant glaciers serve as reminders of the powerful and massive glaciers that shaped the landscape. All the while, rainfall and freeze-thaw cycles cause landslides and rockfalls.”

NPS Geologic Resources Inventory base map.

Stratotypes in John D. Rockefeller, Jr. National Memorial Parkway

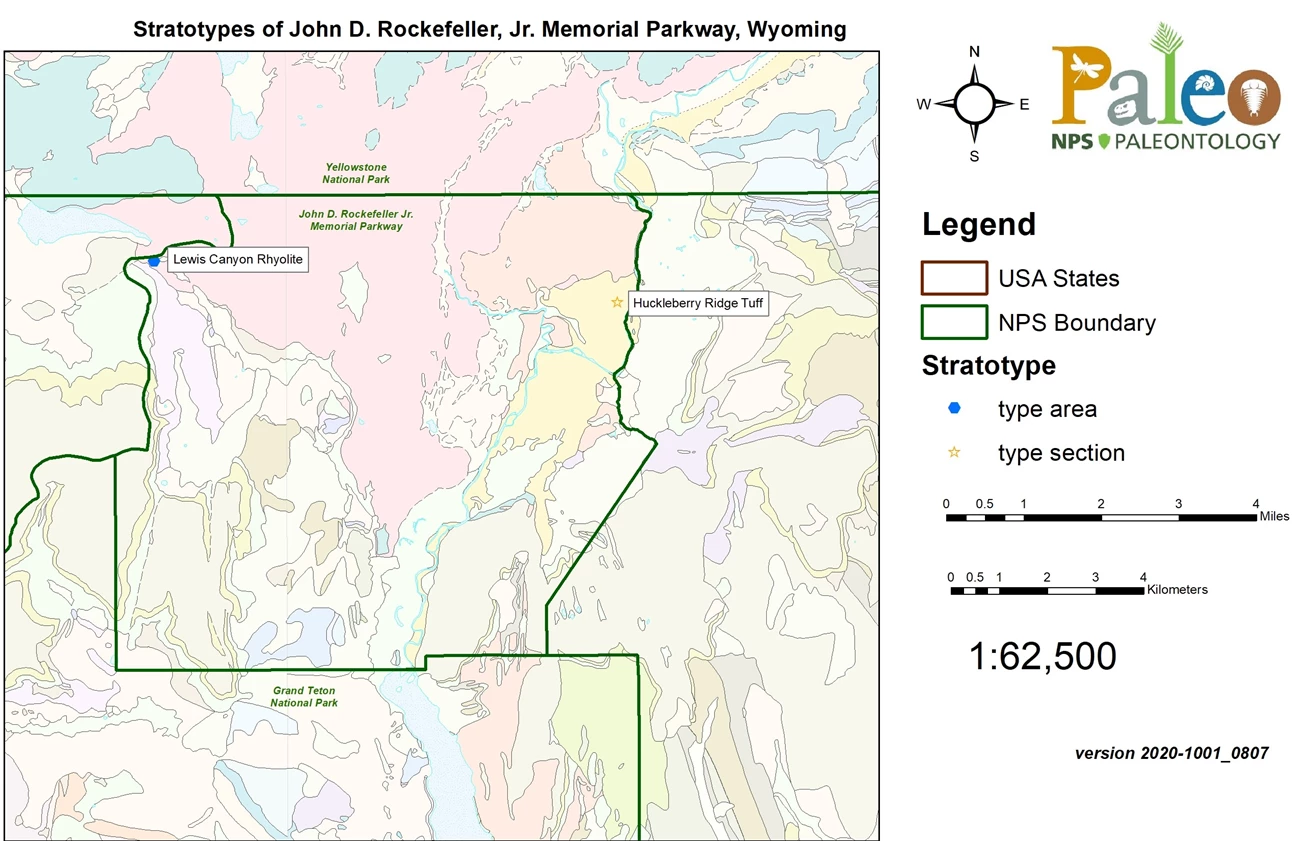

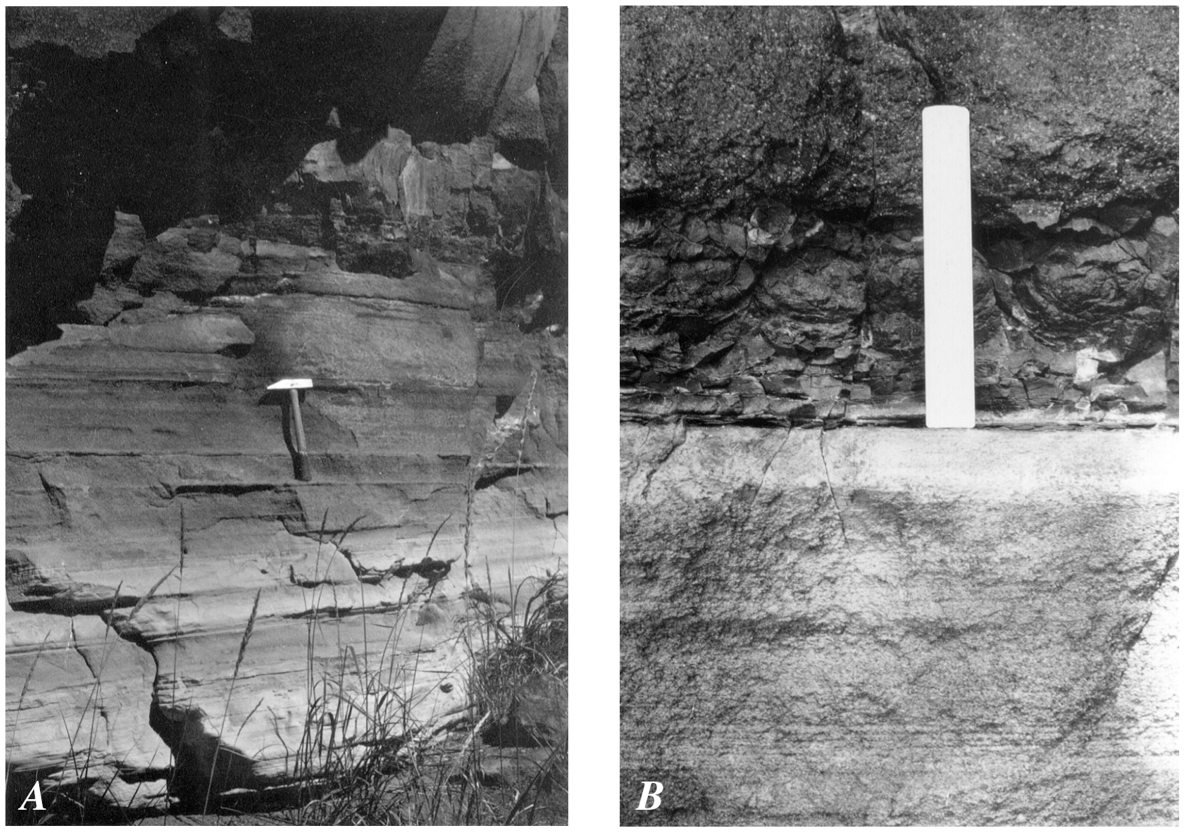

JODR contains one type section and one type area, both of which are associated with Yellowstone volcanism (see Table below; Figure 17). The one type section of JODR is the Pleistocene-age (Quaternary Period) Huckleberry Ridge Tuff, the oldest ash-flow sheet of the Yellowstone Group, dating to approximately 2.1 Ma. The Huckleberry Ridge Tuff consists mainly of welded ash-flow tuff that is predominantly devitrified, containing major phenocrysts of quartz, sanidine, and sodic plagioclase with minor phenocrysts of oxides, clinopyroxene, fayalite, zircon, hornblende, allanite, and chevkinite (Christiansen and Blank 1972). Christiansen and Blank (1972) designated the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff type section as the cliff exposure at the head of a large landslide 1.8 km (1.1 mi) N10° E of the Snake River bridge at Flagg Ranch along the John D. Rockefeller highway about 3 km (2 mi) south of the South Entrance of YELL (Figure 17). The type section is approximately 170 m (560 ft) thick and consists of welded phenocryst-rich rhyolitic ash-flow tuff overlying Cretaceous sandstones and shales (Figure 18; Christiansen and Blank 1972).

| Unit Name (map symbol) | Reference | Stratotype Location | Age |

|---|

Geologic Time Scale

Location Map

NPS Geologic Resources Inventory base map.

Figure from Christiansen (2001).

Ash flows of the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff type section are divided into three members due to significant changes in welding and minor variations in phenocryst content (Christiansen 1979; Christiansen and Blank 1972). The oldest member (A) is approximately 45 m (150 ft) thick and contains abundant (40–50%) phenocrysts at its base that become less abundant in the upper 15 m (50 ft). The middle member (B) is approximately 30 m (100 ft) thick and has a thin, phenocryst-poor base with a zone of abundant large phenocrysts above it (Christiansen and Blank 1972). The top of member B contains distinct dark crystallized pumice that is overlain sharply by member C (Christiansen and Blank 1972). Member C is approximately 95 m (310 ft) thick and is characterized by smaller, moderately abundant phenocrysts than the other underlying members (Christiansen and Blank 1972).

The one geologic type area of JODR is for the Pleistocene-age Lewis Canyon Rhyolite. Stratigraphically, the Lewis Canyon Rhyolite overlies the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff and consists of several bulbous, non-stratiform rhyolitic lava flows dated to approximately 0.85 Ma (850,000 years ago) (Christiansen and Blank 1972; Christiansen 2001). The rhyolite is characterized as containing 30–40% phenocrysts, including abundant sodic oligoclase with smaller, less abundant phenocrysts of quartz, sanidine, clinopyroxene, and opaque oxides (Christiansen and Blank 1972). Christiansen and Blank (1972) designated the type area as the north side of Glade Creek, between the Snake River and the east end of Grassy Lake Reservoir (Figure 17). In this area the Lewis Canyon Rhyolite is represented by well-exposed, 200 m (660 ft) thick flows that occur along the meadows on the north side of Glade Creek. The type area rhyolite overlies the Huckleberry Ridge Tuff and Cretaceous sedimentary rocks and is overlain by the Lava Creek Tuff (Christiansen and Blank 1972).

Type Section Inventory Report—Greater Yellowstone Inventory & Monitoring Network

The information on this page is excerpted from a report covering four parks within the Greater Yellowstone Inventory and Monitoring Network (GRYN):

The full Network report is available in digital format from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2280034

Please cite this publication as:

Henderson, T., V. L. Santucci, T. Connors, and J. S. Tweet. 2020. National Park Service geologic type section inventory: Greater Yellowstone Inventory & Monitoring Network. Natural Resource Report NPS/GRYN/NRR—2020/2198. National Park Service, Fort Collins, Colorado.

Leave No Trace—Protect Type Sections for Science

Many type sections and paleontological sites are vunerable to damage from careless visitation and over-use. Be sure to practice Leave No Trace princples whenever you are in the outdoors. Of particular importance at geoheritage sites is to:

-

Travel and camp on durable surfaces, and

-

Leave what you find.

If you see signs of vandalism or someone acting inappropriately during your visit to a park site, please contact a ranger at the park or make a report through NPS Investigative Services.