Last updated: May 19, 2025

Person

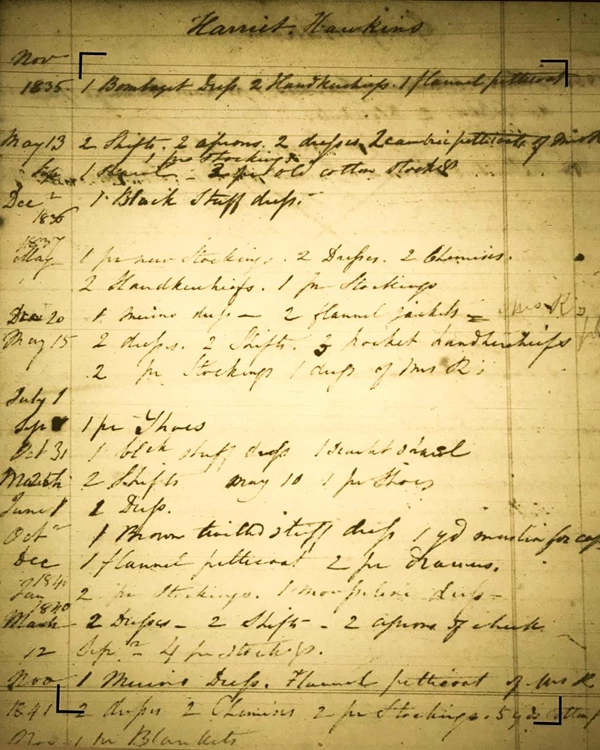

Harriet Hawkins

Courtesy, Maryland Center for History and Culture, MS. 691, Ridgely Account Books

Another key member of the household was Harriet Hawkins (1807-lv.1886), who appears to have been head dressmaker. (Her daughter Sarah assisted her as a seamstress.) Similarly to Mark Posey and Lucy Jackson, Harriet received finer articles of clothing, accessories such as bonnets, and Ridgely family hand-me-downs. Harriet's importance to the story of enslavement at Hampton, however, goes deeper than her domestic role. The story of Harriet and her children speak to the role of privilege in shaping individual lives.

Harriett Hawkins was at Hampton throughout John and Eliza Ridgely's time. However, she is also listed in certain records, such as the "Shoe List," from the time when John's father, Charles Carnan Ridgely, was still alive. However, since she is not recorded in the his estate records, she cannot have been his property. Instead, it is likely that she was enslaved by John Ridgely himself. From an account in the G. Howard White Papers in the Maryland State Archives on November 3, 1827, is found the entry "Harriet (Mr. J. Ridgely) 1 [pair of shoes]. In June of the same year, the list includes "June 19, made 1 pr fine for Harriet Hawkins."

Harriet was born about 1807. Harriet was only 17 years old when she was sexually assaulted by John Ridgely and became the mother of his son, Charles Hale Brown. The power dynamics of enslavement negate the idea of consent by the enslaved. This was in 1824, between the time of the death of John's first wife Prudence Gough Carroll Ridgely in 1822 and his second marriage to Eliza Eichelberger Ridgely in 1828.

According to her family history, Charles Hale Brown was sent to Boston between the ages of 14 and 17 for an education. Documents in the Chattle Records of Baltimore County record that Brown was manumitted from chattel slavery by his father, John Ridgely, on August 28, 1846 at the age of 22 years old. One possible reason for the timing was the imminent departure of John and Eliza Ridgely on an extended trip abroad. Whatever the case, Charles Hale Brown was the only one of the numerous enslaved people John held in bondage to have been freed before the Maryland Emancipation in November of 1864.

Charles Hale Brown was also a well-known figure in the Baltimore community. His family believed that he worked principally as a doorman for the Baltimore Club. His obituary in the Sun from June 1911 also states:

Old Colored Servant Dead. Charles H. Brown, colored 88 years old died Saturday at 222 West Chase Street. He had lived 25 years in the family of Mrs. J. Hall Pleasants, also 25 years at the Baltimore Club, and was cared for in his late years by Mr. John Pleasants and members of the Baltimore Club. He leaves a widow and three children.

Census records confirm the address and his wife (Sarah, b. 1842) and children's names: James E. (b. 1867), Cornelius Dowling (b. 1872), and Mary Virginia (b. 1868). Mary Virginia Brown, Mrs. Samuel F. Williams, was the grandmother of Genevieve Mason, who visited with Hampton staff in 1995, showing family photos and documents, including a photo of Brown himself. It is noteworthy that James E. Brown married a white woman from Washington D.C., and that he and his son Lawrence are later listed as white in census records.

As a house servant who assisted with making, mending, and altering clothing, Harriet Hawkins would have been regularly in contact with Eliza Ridgely. The records are silent on whether Eliza knew about Harriet's son. Nevertheless, they do confirm certain aspects of what appears to be special treatment.

In the 1840s and early 1850s, Harriet Hawkins had several additional children: Sarah (b. 1841), Nelson (b. 1843), Mary (b. 1845) and Louisa (b. 1854, when Harriet was in her late 40s). All the children but Mary were clearly house servants, and Nelson's clothing indicates he served as both an apprentice waiter and cook. All these children are recorded using the surname Hawkins. The identity of the father of these children is still unknown. However, a free Black laborer named Nelson worked at Hampton for two years in 1842 and 1843. It seems possible, given the common pattern of family names, that Harriet’s son Nelson (b. 1843) might have been named for his father. Unfortunately, no more is known about “Negro Nelson,” as he is recorded in John Ridgely’s Memorandum Book, which did not note a surname. There was an also an enslaved laborer at Hampton named John Hawkins in the 1830s, but he sought freedom in 1844. He probably has no familial connection to Harriet and her family.

When the youngest child Louisa was born, Harriet's marital status became as issue for Didy Ridgely. She commented in her diary:

Harriet Hawkins had a little girl born this morning at 1 o’clock A.M. I hope God’s blessing upon my scripture lessons may prevent such misconduct & sin among our younger servant girls, & save them from the effect of bad examples.

Harriet Hawkins and her younger children were not released from slavery until 1864, nearly 20 years after her eldest son’s manumission. In freedom, they all moved to Baltimore City, to Madison Avenue in the fashionable Mount Vernon area. Harriet is listed in City Directories as a dressmaker, a more highly skilled profession than seamstress. Sarah followed in her mother's footsteps, being listed as a seamstress.

Her sons were prominent in several professional endeavors including a leading funeral home that survives today. It is possible that through Charles and Julia Hawkins’ family, Harriet Hawkins of Hampton may have hundreds of descendants currently living in the Philadelphia area. Several older family members attended St. Simon Cyrenian Episcopal Church in south Philadelphia and some may still be members of that historic African American congregation.