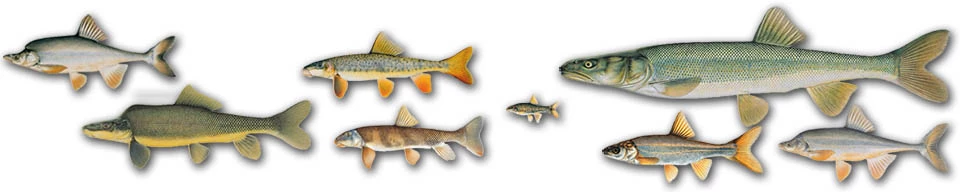

Illustrations by Joe Tomelleri Grand Canyon has a distinctive collection of native fishes, hailing from only two families: minnows (Cyprinidae) and suckers (Catostomidae). Many of the native species are found only in the Colorado River basin. This very high percentage of endemic fish species (species native and restricted to Grand Canyon geographically) likely results from the geographic isolation of the Colorado River system, and to the highly variable natural environments, flow and temperature regimes of the river and its tributaries. The river's unusual native fish assemblage is as iconic a characteristic of the Grand Canyon as its towering cliffs, other endemic species such as the Grand Canyon rattlesnake, and spectacular scenery. Humpack Chub (Gila cypha)

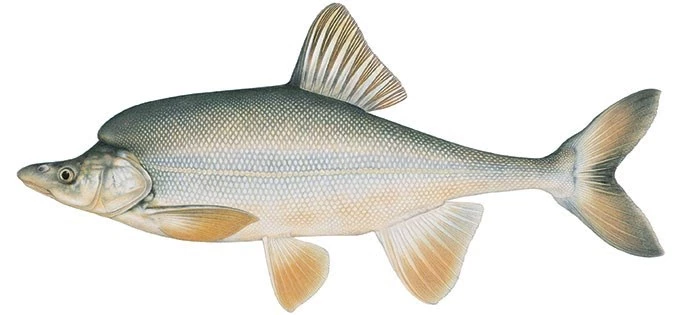

Illustration by Joe Tomelleri

Status: ThreatenedHumpback chub are one of three species of chub that once inhabited the canyon, and are the only chub species still found in the Grand Canyon. The species is currently listed as threatened, with remaining populations found in six Colorado River basin locations in western Colorado, Utah, and Grand Canyon. The largest of these populations is in Grand Canyon National Park. In fact, the confluence of the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers in the Grand Canyon currently supports the largest of the six remaining populations of humpback chub in the world.

Visit our keyboard shortcuts docs for details

The humpback chub (Gila cypha) is an unusual-looking member of the minnow family that is endemic, or native, to the Colorado River basin. These fish, which can live as long as 30 years and reach lengths of almost 20 inches, are characterized by large fins and pronounced humps behind the heads of adults. The species is currently listed as threatened, with remaining populations found in six Colorado River basin locations in western Colorado, Utah, and Grand Canyon.

The most striking characteristic of these large silver minnows is the pronounced fleshy hump located behind their heads. However, juvenile humpback chub do not yet have these distinctive humps; the fish start developing them at three to four years of age.

Water temperature in the Grand Canyon can be a limiting factor for humpback chub, which require water temperatures of at least 61º F to spawn. Since Glen Canyon Dam draws water from deep beneath the surface of Lake Powell, some parts of the Colorado River are now too cold for humpback chub to spawn, except in warmer water areas such as springs, tributary inflows, and in western Grand Canyon. Prolonged drought and climate change have led to low Lake Powell levels, and consequently, warmer surface water is being drawn through the dam. This warming has benefited humpback chub and other native fishes downstream. Other tributaries, such as Bright Angel Creek, Havasu Creek, and Shinumo Creek have water temperatures during spring and summer months that are warm enough for humpback chub spawning and for young fish to grow and survive.

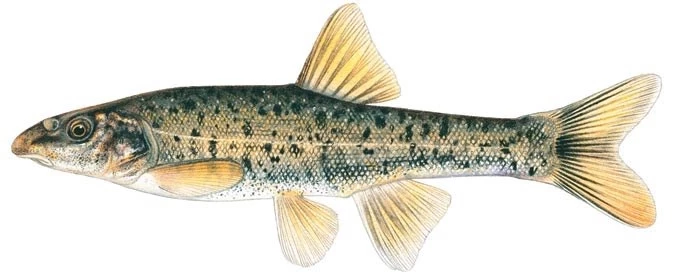

Current conservation measures for the recovery of humpback chub in Grand Canyon include translocations of humpback chub into tributaries, invasive fish control, monitoring of populations throughout the mainstem and tributaries, and the establishment of a refuge population of humpback chub at the Southwestern Native Aquatic Resource and Recovery Center US Fish and Wildlife Service fish hatchery in New Mexico. Grand Canyon's Other Native FishesSpeckled Dace (Rhinichthys osculus)

Flannelmouth Sucker (Catostomus latipinnis)

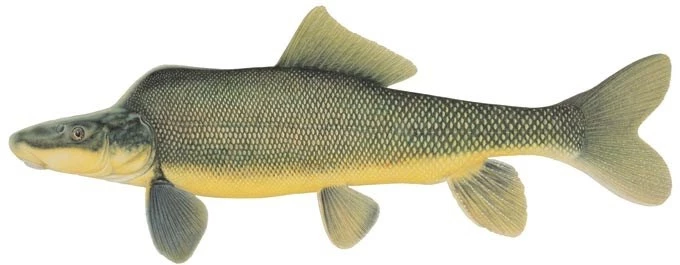

Flannelmouth suckers are the largest species of native fish still relatively abundant in the Grand Canyon. Following increases in the last decade, the flannelmouth sucker population appears to be widely distributed and stable. However, threats to the species remain because of predation by invasive rainbow and brown trout, and because the cold water temperatures released through Glen Canyon Dam may impact their ability to successfully reproduce and grow to adulthood near the dam. The species’ range has been reduced following water development, habitat loss, and invasive species’ introductions throughout the Colorado River basin, and remains a range-wide species of conservation concern. Flannelmouth suckers mostly live in the mainstem Colorado River in Grand Canyon, preferring pools and deep runs. These large fish reach a maximum length of 24 inches (600 mm) and may live longer than 30 years. They spawn in or near many of the larger Colorado River tributaries in Grand Canyon, including the Paria River, Little Colorado River, Bright Angel Creek, and Havasu Creek. Juvenile fish may drift downstream for long distances, and adults make long-distance movements to and from spawning areas.

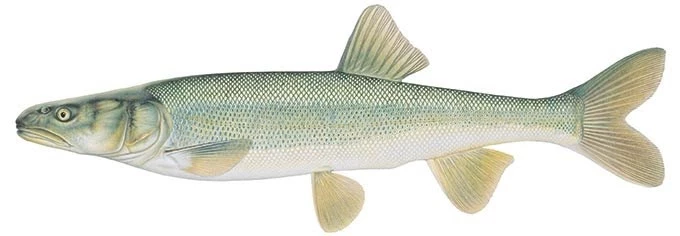

Bluehead Sucker (Catostomus discobolus)

In Grand Canyon, populations of bluehead suckers are found in major tributaries such as the Little Colorado River, Havasu Creek, and Bright Angel Creek. The population of bluehead sucker in Shinumo Creek was lost following a fire and ash-laden flood in 2014, and others are threatened by invasive predators, and drought, which limits spawning success. The species prefers rocky substrates that are cleaned of fine sediment by spring flooding, and moderate to fast stream velocity. Bluehead suckers reach a maximum length of about 20 inches (500 mm), and feed on aquatic invertebrates and organic debris. The species has a specially-adapted cartilaginous plate on its lower lip to scrape algae from rocks on the stream bottom. Razorback sucker (Xyrauchen texanus)

Status: EndangeredRazorback suckers have a bony keel on their backs. They are the largest species of suckers that live in the Colorado River and reach a maximum length of 36 inches (900 mm). They may live 40 years or more. They feed on a variety of insects, crustaceans, and detrital matter.The species was listed as endangered in 1991; critical habitat for the species includes all of the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park. The razorback sucker was thought to be extirpated, or locally extinct, from Grand Canyon until 2012 when several adult razorback suckers were captured in the western Grand Canyon during routine sampling. An expanded monitoring effort beginning in 2014 found that razorback sucker were spawning in Grand Canyon and were moving between the canyon and Lake Mead. In recent years, these movements have slowed and larval catches have also decreased. The National Park Service is currently working with cooperating agencies, universities, consultants, and Tribes to evaluate the status of the species in Grand Canyon and consider potential management actions to conserve the species. Prior to the constructions of dams on the Colorado River and other human-caused alterations to their habitat, razorback suckers were widely distributed in the Colorado River and its major tributaries, and were typically found in calm flat-water reaches. There are at least ten historical records of razorback suckers caught in Grand Canyon, including a specimen caught in Bright Angel Creek in 1944. To understand more about the razorback suckers, the NFEC program has assisted in the release of sonic- and radio- tagged razorback suckers for tracking since 2014. The most recent release of 20 adults with sonic-tags during February 2021 near Phantom Ranch and downstream of Separation Canyon was a highlight of the program. Tracking the fish released will help us understand movements and habitat use of razorback sucker. Grand Canyon's Extirpated Fish SpeciesThree of the eight species of native species of fishes are no longer found in Grand Canyon National Park.

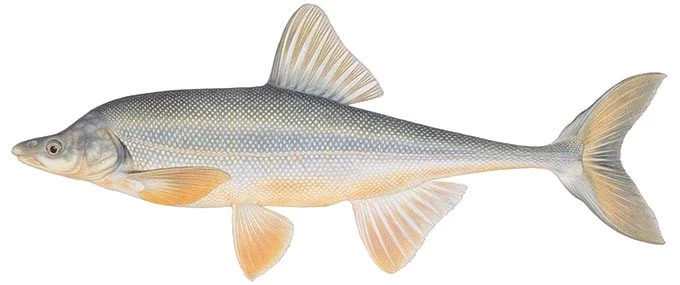

Colorado pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus lucius)

Status: EndangeredThe Colorado pikeminnow is endemic to the Colorado River and is the largest member of the minnow family on the continent, with a maximum length of six feet (72 inches or 1800 mm). The Colorado pikeminnow is extirpated from Grand Canyon, with the last verified record in 1972. Pikeminnow are still found in the upper end of Lake Powell, in the San Juan River, and in the Yampa and Green rivers in Dinosaur National Park. The Colorado pikeminnow was the top predator in the Colorado River, feeding on all species of fishes. These torpedo-shaped fish have large toothless mouths and are effective predators.

Bonytail (Gila elegans)

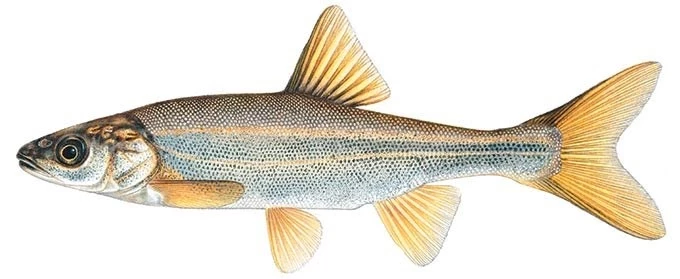

Status: EndangeredBonytail is the most critically endangered of the Colorado River's native fishes. An intensive stocking program releases large numbers of hatchery-raised bonytail into the wild every year in the Upper Basin of the Colorado River, but their survival is low and re-establishment of a wild population has so far been unsuccessful. A number of hatcheries have refuge populations of the species.Bonytails are closely related to humpback and roundtail chubs and are streamlined, powerful swimmers with large fins. They reach a maximum length of 22 inches (550 mm). They are gregarious schooling fish that were historically very abundant in portions of the basin, probably particularly in the rich Colorado River delta region. Relatively little is known about the species habitat in the wild, or its previous distribution in Grand Canyon. Records are known from Bright Angel and Phantom creeks in the early 1940s, and bonytail skeletal remains were recovered from Stanton's Cave. Roundtail chub (Gila robusta)

Roundtail chub are one of three species of chub historically found in Grand Canyon. The species was likely extirpated from the canyon by the late 1960s. Although their populations have decreased because of human-caused changes to the Colorado River system, including introduction of invasive warm-water fish species, and the construction and operation of dams and water diversions, roundtail chub are the most abundant of the river's three species of chub outside of Grand Canyon. They are similar in size to humpback chub (20 inches or 500 mm), and are closely related. Remaining roundtail chub populations in the Colorado River Basin are largely restricted to tributary streams and canyon reaches, and populations are often found near humpback chub populations. The species was first described from specimens collected near Grand Falls on the Little Colorado River in the 1850s. Roundtail chub have been absent from Grand Canyon since the 1960s. |

Last updated: January 8, 2023