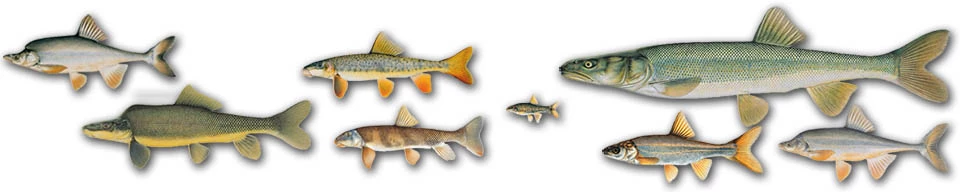

The Colorado River through the Grand Canyon is a dynamic ecosystem. Before the construction of dams upstream, the river had highly variable flows and seasonal fluctuations with which the native fishes evolved and thrived. The harsh environment and isolation from other rivers due to the unique geologic history of the Colorado River Basin resulted in fish species specialized for this ecosystem. The majority of these fish are found nowhere else. Grand Canyon continues to support abundant and self-sustaining populations of native fishes including the humpback chub, speckled dace, and bluehead and flannelmouth suckers. As are many arid-land fishes, the humpback chub is listed under the Endangered Species Act as threatened, and bluehead and flannelmouth suckers are imperiled and the subject of a conservation agreement and strategy. Endangered razorback sucker are currently rare in Grand Canyon, while bonytail, roundtail chub, and Colorado pikeminnow are extirpated.

Dams upstream and downstream of the Grand Canyon have led to a fragmented river system with profound changes in sediment, water volume, and water temperatures. Despite these changes and through active conservation efforts in coordination with other agencies and stakeholders, the park continues to support the largest remaining humpback chub population, and contributes to the only razorback sucker population that has not been maintained by hatchery production and stocking, located in Lake Mead. Beginning in 2009, the Native Fish Ecology and Conservation program (NFEC) at Grand Canyon National Park developed and implemented a Comprehensive Fisheries Management Plan that includes actions to address remaining threats to maintain and restore native fish communities. Despite immense changes to the natural regime, the Grand Canyon is currently a stronghold for native fishes in the Colorado River basin.

Threats to Native Fishes in a Changing Ecosystem

Flow, temperature, and sediment changes – The construction and operation of Glen Canyon Dam profoundly changed the aquatic and riparian ecosystem downstream. The life histories of Grand Canyon’s native fishes evolved in an ever-changing and flood-prone environment. The colder, more stable temperatures and flows from the dam have favored introduced invasive sport fishes and have limited the ability of native fishes to reproduce in some areas. The NFEC program was initiated in 2009 to implement conservation measures designed to offset the impacts of Glen Canyon Dam, including through translocations of humpback chub, non-native fish control, and adaptive management of razorback sucker. NFEC staff actively participate in the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program to represent Grand Canyon’s interest in protecting fish and other resources along the Colorado River.

Non-native/Invasive species – Grand Canyon’s native fishes co-evolved with only a single, large-bodied, toothless predator, the Colorado pikeminnow. The “humpbacked” body shape of species such as the humpback chub and razorback sucker are thought to be a defense mechanism against the large mouth of the pikeminnow. Native fishes lack evolved defenses to avoid predation by invasive predators like trout, bass, or catfish, which have teeth and even larger mouths than native pikeminnow. Minimizing the impact of competition with, and predation by, invasive fishes on the native fish communities in Grand Canyon is a top priority for the NFEC program. The primary focus of invasive fish removal and research targets brown and rainbow trout, which are currently considered the most abundant invasive predators in the Grand Canyon. Trout were first introduced into Grand Canyon’s tributaries in the 1920s and 1930s. Closure of the newly constructed Glen Canyon Dam in 1963 created favorable conditions in the Colorado River and allowed trout stocked in tributaries to expand into the mainstem. Due to these favorable conditions, the Arizona Game and Fish Department established a rainbow trout fishery between Lees Ferry and the dam in the early 1960s after closure of the gates at Glen Canyon Dam.

Non-native fish control activities include trout population suppression using electrofishing throughout Bright Angel Creek and its tributaries, and the installation and operation of a weir to capture and remove trout on spawning runs from the Colorado River. The goals of this operation are to restore the native fish community and reduce risks to endangered humpback chub system-wide, as Bright Angel Creek was historically the primary source of brown trout in Grand Canyon. Additionally, Grand Canyon National Park is combating the threat of non-native smallmouth bass to its delicate aquatic ecosystem through techniques like electrofishing, while also implementing long-term strategies to manage water flows in the Colorado River. With support from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act funding, the National Park Service is using a coordinated three-park approach to manage invasive species and restore the vital Colorado River.

Fragmentation – Hoover and Glen Canyon dams are among the 18 major dams constructed throughout the Colorado River basin that have cut off migration routes for endemic native fishes. Among other factors, the loss of these migration routes between spawning and rearing habitats is a primary cause of extirpation of Colorado pikeminnow and the decline of razorback sucker.

Less discussed is the impact of the isolation of tributaries from the Colorado River mainstem due to suppression of historic seasonal high flows. Cascades or waterfalls within 200 meters of the mouths of Shinumo and Havasu Creeks are no longer inundated by Colorado River floodwaters that originate as snowmelt in the Rocky Mountains. Without high Colorado River flows, fish communities and spawning habitat are isolated in these tributaries. Native fishes are unable to re-colonize habitats following naturally occurring disturbances such as fires or floods. However, the isolation of these tributaries from the mainstem may also provide protection from invasive predators found only in the mainstem. This scenario provides opportunities to restore or maintain native fish communities and naturally functioning tributary ecosystems. Habitat in Grand Canyon tributaries is minimally-impaired relative to the mainstem Colorado River. These tributaries also provide opportunities to study native fish ecology to inform future management actions. The NFEC program currently manages, monitors, and researches the population dynamics of fish communities primarily in Shinumo, Havasu, and Bright Angel Creeks.

|

Last updated: October 2, 2024