|

Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, churches, and the many, many park designs.

Olmsted Archives Louisville Parks and Parkway System (Louisville, KY)In 1891, Frederick Law Olmsted was invited to Louisville, Kentucky by a group of prominent citizens who formed the Salmagundi Club. They asked Olmsted to survey the land the Club had already acquired, creating one of five Olmsted systems in the country where parks and boulevards connect, creating a network of green space. The final design of the type for Olmsted Sr., it was one of two park systems designed by all three Olmsteds.Louisville’s Park System is anchored by three large parks along the perimeter of the city: Iroquois, Cherokee, and Shawnee. Each park takes advantage of the unique natural features in the area, such as diverse topography, riverfront views, and native woodlands. In addition to designing the city’s park system, the Olmsted firm also helped plan the city, residential subdivisions, estates, cemeteries, institutional and religious grounds, country clubs, and gardens. In all, the Olmsted firm designed eighteen parks, squares, and playgrounds throughout the city, as well as six parkways.

Olmsted Archives Commonwealth Avenue (Boston, MA)While Commonwealth Avenue’s Mall was designed in the French Boulevard style in 1856 by Arthur Gilman, Frederick Law Olmsted was asked to extend the mall westward from Massachusetts Avenue to Charlesgate. Partnering with his Arnold Arboretum collaborator Charles Sprague Sargent, the pair began providing advice on tree planting patterns.In the Mall’s thirty-two additional acres, Olmsted and Sargent suggested that the design must “obtain . . . the uniformity which seems to us essential to the future beauty and dignity of the finest street in the city." The pair also suggested removing existing trees and replacing them with two single rows of European Elms. Fearing public outcry from removing existing trees, Boston City Council rejected that suggestion. Despite this, Commonwealth Avenue Mall is still known for its American Elms, some of which are able to survive Dutch Elm Disease, which has devastated the species. Despite much of Olmsted and Sargent’s design being redesigned, it followed the original suggestions.

Olmsted Archives Back Bay Fens (Boston, MA)By the 1850s, three factors motivated the filling of Back Bay. Dams were created around Boston in the early 1800s, which no longer caused the tides to change twice a day, instead having sewage and waste sit stagnant, causing horrible pollution. Boston was also becoming way too overcrowded, with 100,000 people living on 1,000 acres of land. An increase in poor immigrants led Boston leaders to think of ways to keep wealthy families in the area, and their solution was to create a new neighborhood.In the mid-1870s, the Boston Park Commission opened up a design competition for the first segment of the Boston Park System, which had to be Back Bay because it needed to be cleaned up. Frederick Law Olmsted chooses not to enter the competition and when he is asked to judge, he refuses, saying how he mistrusted competitions like this. One of the biggest projects undertaken by any city at the time, with around 2,000 acres being worked on, Back Bay would set the stage for Olmsted’s later projects of even more ambitious dimensions and be a defining factor in moving his family from New York City to Brookline. Olmsted came into the project believing that parks are not an ornamental part of the city, but integral in its fabric and a force of growth. However, at Back Bay the design was less a park and more a sanity improvement. Olmsted began work by conducting a four-hour conference with Boston’s city engineer and superintendent of sewers. Olmsted would stay in contact with the city engineer throughout his entire work for the Boston Parks system. Those conversations proved useful, as sewers were constructed, allowing for a basin to store water.

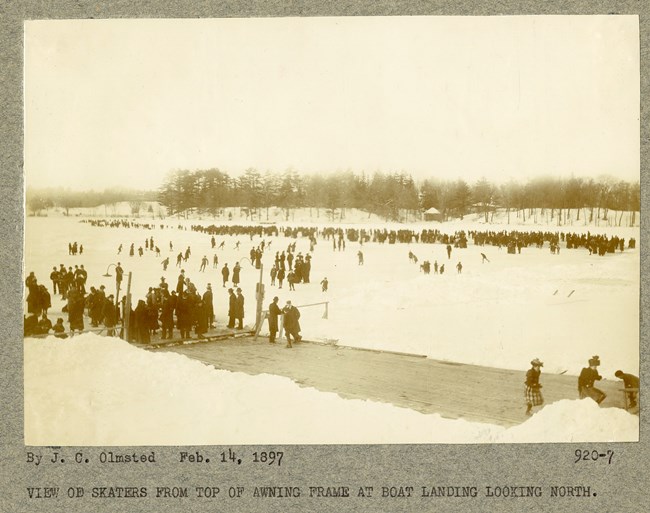

Olmsted Archives Jamaica Park (Boston, MA)Prior to Frederick Law Olmsted’s move to Brookline, and his involvement with the entire Boston Park System, Jamaica Pond served as a popular summer resort for wealthy locals. In 1882, Olmsted described the area as “a natural sheet of water, with quiet graceful shores, rear banks of varied elevation and contour, for the most part shaded by a fine natural forest-growth.”At Jamaica Pond, Olmsted’s work can be described as a minimalist design, adding vegetation to compliment the natural scenery he admired. There was no need to regrade or reshape any of the land, and simple walkways were added to encircle the pond.

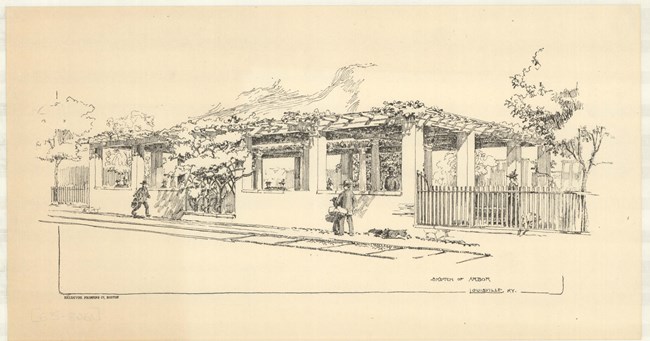

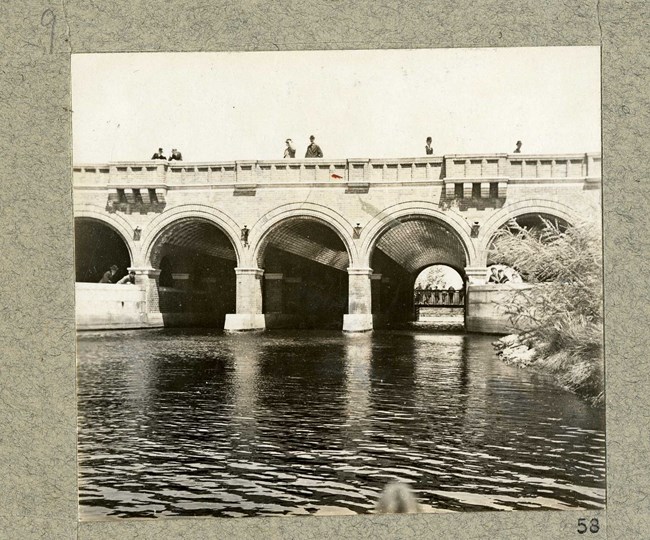

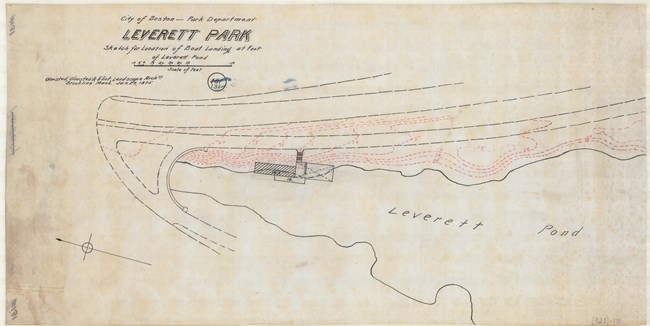

Olmsted Archives Leverett Park (Boston, MA)Just like his design at Jamaica Pond, the inherent beauty of the land allowed Frederick Law Olmsted to make minor changes to Leverett Park, which would be renamed years later in Olmsted’s honor. Also like another Boston design, the Riverway, Olmsted Park incorporates a diverse collection of stairs and bridges.Viewing just the area, Olmsted stated that “the locality is at present very attractive, including as it does, Ward's Pond with its verdure-clad, precipitous banks, a steep wooded hill, several groves and two meadows . . .". Olmsted wanted to reveal the natural features in the area, so he designed pathways and planting patterns creating a series of vistas. A majority of Olmsted Park is heavily wooded, except for Leverett Pond, the western border, which provides park patrons with a beautiful vista. This was intentional as Olmsted favored open and closed arrangements together, creating a varied experience for those exploring the park.

Olmsted Archives Fresh Pond Parkway (Cambridge, MA)While work on Fresh Pond Parkway is credited to Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot, Charles Eliot is deserving of most of the credit for Fresh Pond and Fresh Pond Parkway, and many of the Olmsted designs in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Eliot would be a crucial character in providing a guiding hand for the early activities of the Cambridge Park Commission.In 1893, after Cambridge acquired Fresh Pond to preserve its water supply, Eliot was invited to inspect the site for a possible park. Eliot observed that “On the west is Fresh Pond, with an area of one hundred and fifty-five acres. Along the whole length of the southern boundary of the city stretches the Charles River … Here is a total of eight hundred acres of permanently open space provided by nature without cost to Cambridge. . . If Cambridge is to invest money in public recreation grounds, a just economy demands that such money shall first be placed where it will bring into use for public enjoyment these now unused and inaccessible spaces with their ample air, light, and outlook.” Though it happened after Eliot succumbed to spinal meningitis in 1897, Fresh Pond and Fresh Pond Parkway were brought into the public domain. Today, Fresh Pond Parkway is still lined with oaks, as Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot recommended.

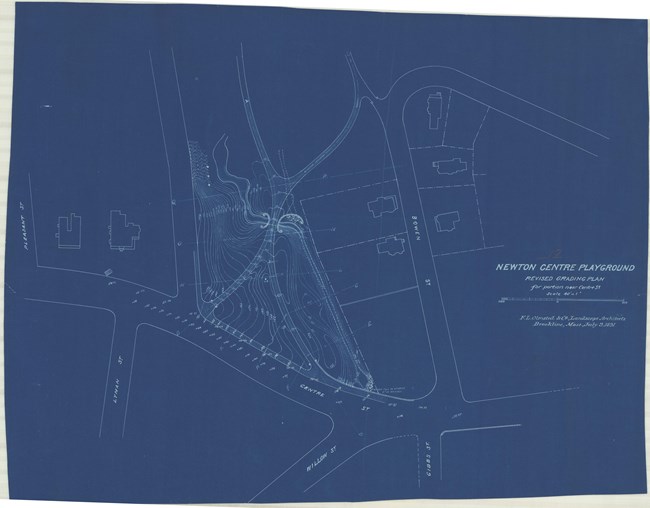

Olmsted Archives Newton Centre Playground (Newton, MA)Newton Centre Playground was created out of civic interest and involvement, most of it coming from local neighbors. The Newton Centre Improvement Association provided funds for the city’s first public playground, with its initial design prepared by the F.L. and J.C Olmsted firm. Originally designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, firm member Herbert J. Kellaway took over the design, and after starting his own landscape architecture firm, submitted a revised plan in 1908.Originally named William C. Brewer Playground after the organizer and first chair of the Newton Playground Commission, the construction of this playground would prompt Newton’s mayor to encourage the development of more playgrounds. Intended to serve a broad audience by balancing the activities of a playground with the calming qualities of a park, Newton Centre Playground was the first in the city.

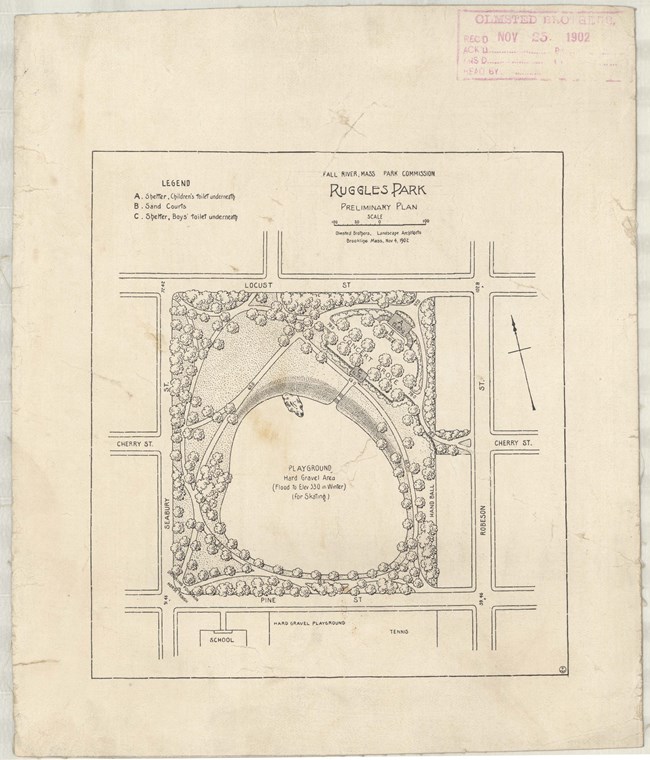

Olmsted Archives Ruggles Park (Fall River, MA)In 1868, the city of Fall River, Massachusetts purchased a section of farmland, known then as Ruggles Grove. Originally lush with trees, by the turn of the century many of those trees were gone and the land was looking worse for wear. By 1901, Fall River had established it’s Parks Commission, and with $182,000 (over $6 million today) they hired Olmsted Brothers to design their parks.John Charles and Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. were hired to redesign Ruggles Park, right in the middle of a working-class neighborhood by tenements and mills. Olmsted Brothers’ design included a ball field, “little folks’ playground”, and gently curving paths. They refashioned exposed ledges into a retaining wall. Construction wasn’t always easy, with Olmsted Jr. writing to contractor Thomas J. Kelley in September 1903, sharing some choice words about Fall River Parks Superintendent Howard Lothrop, and the local workers. Regardless, Ruggles Park was built and today is a small marvel with mature and majestic oak trees planted throughout.

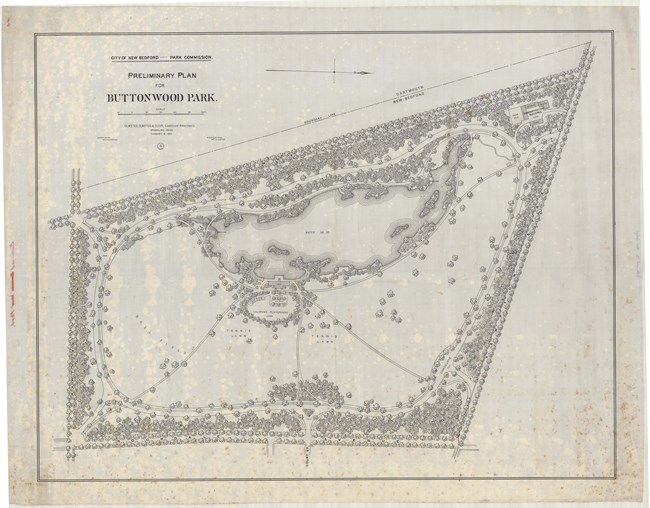

Olmsted Archives Buttonwood Park (New Bedford, MA)In 1895, Olmsted, Olmsted and Eliot were hired to develop a master plan for Buttonwood Park in New Bedford, Massachusetts. Firm partner Charles Eliot prepared the preliminary plan for the park on land at the center of the city. Eliot’s plan included enlarging the 6-acre pond and creating an expansive meadow leading up to the edge of the water. Eliot also suggested space for tennis and ball games, a children’s playground, and a carriage road around the site that would limit vehicular traffic within the park.Both lawn and pond expansion were partially implemented on Buttonwood Park’s 97-acres of land. With its deciduous tree, the open lawn serves as a gathering space while the pond allows for boating, swimming, fishing, and ice skating. While the baseball diamond was added in 1896 and tennis courts in 1909, various other facilities were placed in the park, like a zoo, which submerged the natural setting with buildings.

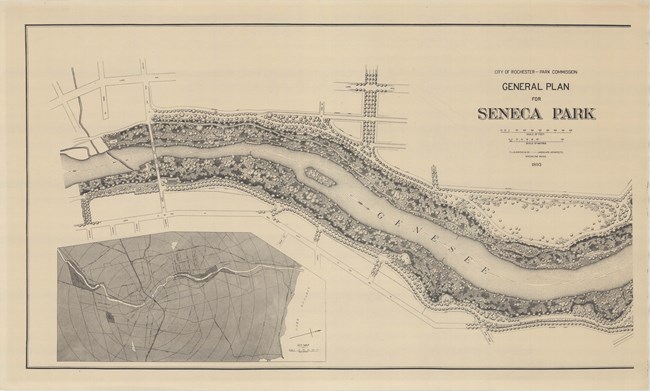

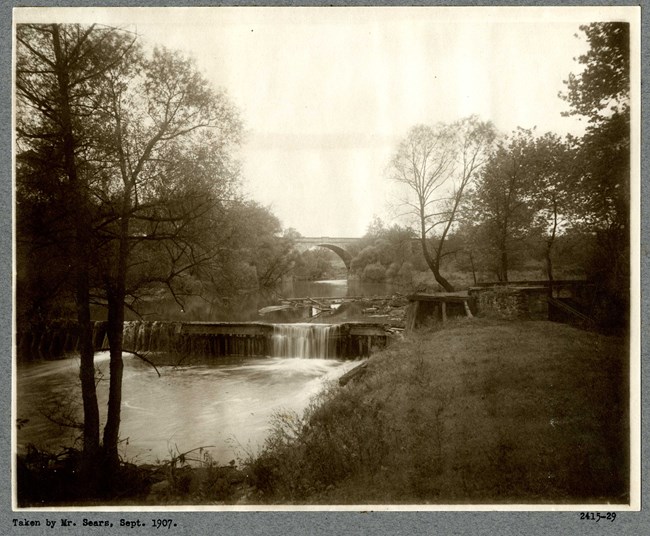

Olmsted Archives Seneca Park (Rochester, NY)At the northernmost section of Rochester New York’s Park System, the 297-acre Seneca Park sits, designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1893. The three-mile park is on both sides of the Genesee River, with the intention to provide public access to the river while also preserving the area from development. The original plan for Seneca Park called for tree-lined carriage drives and a network of paths that would minimize disturbances caused from grading.To prevent erosion and reduce the risk of falling debris, Olmsted included dense plantings along the edge of the gorge. Taking nearly ten years to complete, Seneca Park was designed with picturesque elements. In addition to Olmsted Sr. working on the park, John Charles Olmsted oversaw development from 1901 to 1915.

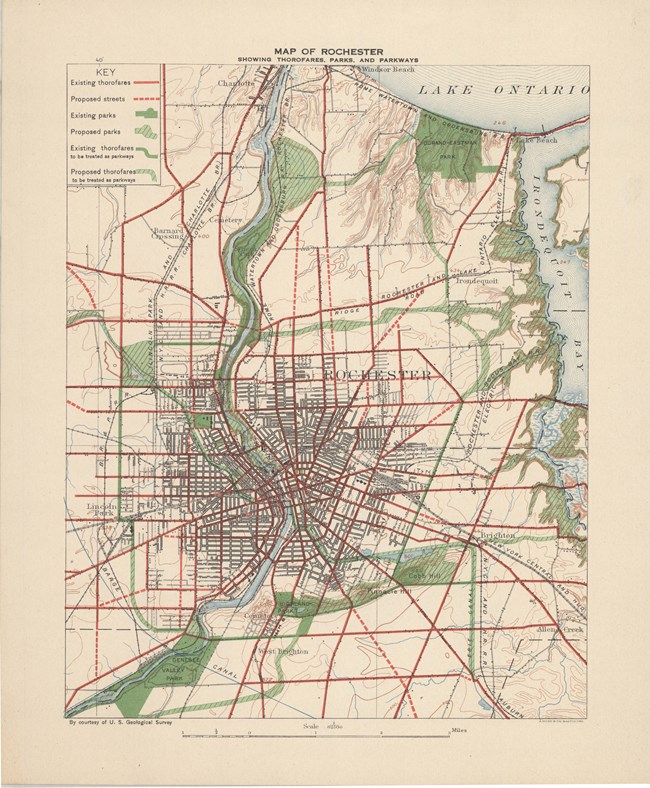

Olmsted Archives Rochester Parks (Rochester, NY)By the 1880s, many local landowners with the desire for a public park would donate their own property for this purpose. In 1888, Rochester, New York’s Board of Park Commissioners had acquired land from locals and hired Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux to develop a comprehensive park system. Olmsted and Vaux proposed three large parks, ranging from 20 to 800-acres, with the hope of capturing the area’s landscape characteristics and scenery.After their father’s death, Olmsted Brothers would continue work on the Rochester Park System. In 1911, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr recommended additional neighborhood parks, reservations, and parkways. Olmsted Brothers continued to consult on Rochester’s Park development until 1915, when the city parks department was replaced by an independent board of park commissioners. In addition to the Louisville Park System, Rochester is the only park system where all three Olmsted’s were involved in planning and design.

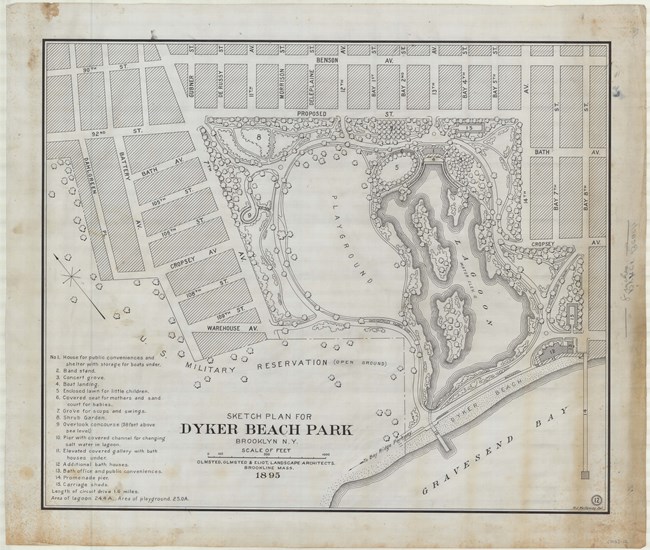

Olmsted Archives Dyker Beach (New York City, NY)In 1895, Brooklyn, New York, still three years away from becoming part of New York City, acquired 144-acres of marshland with the intention of transforming it into a park to serve the waterside neighborhood of immigrants. Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot were hired to transform the marsh into 50-acres of tidal saltwater lagoon surrounded by plantings, a concert grove, playgrounds, and other community amenities.At the same time the firm was working on what would be known as Dyker Beach, they were also planning a parkway that follows the shoreline, connecting to Dyker Beach. Unfortunately, lack of funds and public health concerns ended this addition. Today, little of the original Olmsted design remains, though Dyker Beach remains a popular destination.

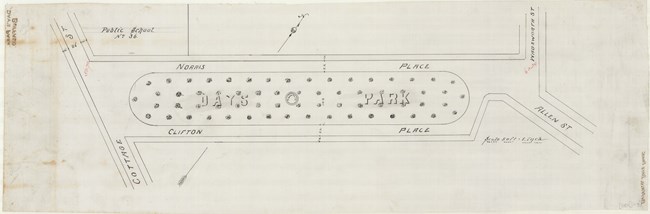

Olmsted Archives Day's Park (Buffalo, NY)In 1886, Buffalo’s Board of Park Commissioners wanted to expand their park system to include not just the large parks and parkways but smaller grounds as well. As the city did with their large parks, they turned to Frederick Law Olmsted for their small ones. In April 1887, Olmsted submitted his plan for Day’s Park. The park was named for Thomas Day, a wealthy early settler of Buffalo who gifted the land for the park in 1859, under the condition the land be made into a park bearing his name.At Day’s Park, Olmsted’s plan provided “a long plat of turf studded with trees, with a fountain in the center…” the fountain was an uncommon feature for one of Buffalo’s Olmsted-designed parks, with Day’s Park being the only one Olmsted designed in Buffalo to include one. Despite the removal of the original fountain in 1923, Day’s Park remains the way Olmsted envisioned it.

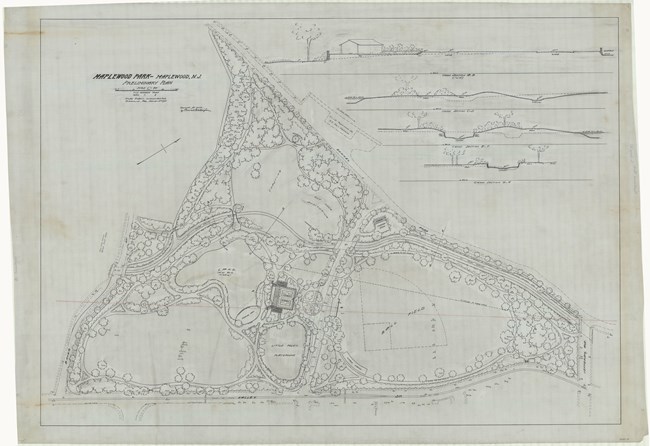

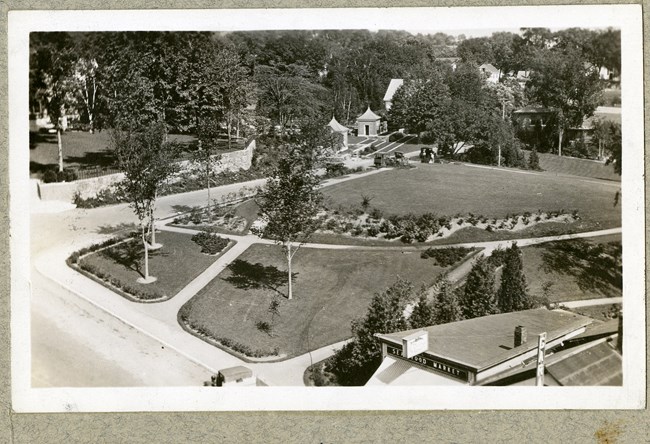

Olmsted Archives Maplewood Park (Maplewood, NJ)Community leaders of Maplewood, New Jersey (originally part of South Orange) were eager to create a recreational area for their residents. In 1922, community members reached out to Olmsted Brothers, requesting a general plan for their new park. The plan for the new park included a pond, playfields, tennis courts, and a memorial to those lost in WWI.Planting at Maplewood Park began in 1923 and was completed two years later, the only aspect of the Olmsted design that was implemented. The relationship between Olmsted Brothers and Maplewood was strained by differing opinions on design choices. One example of this is that Olmsted Brothers preferred a simple piece of granite for the base of the War Memorial, while the Memorial Committee preferred a large boulder, which was eventually chosen.

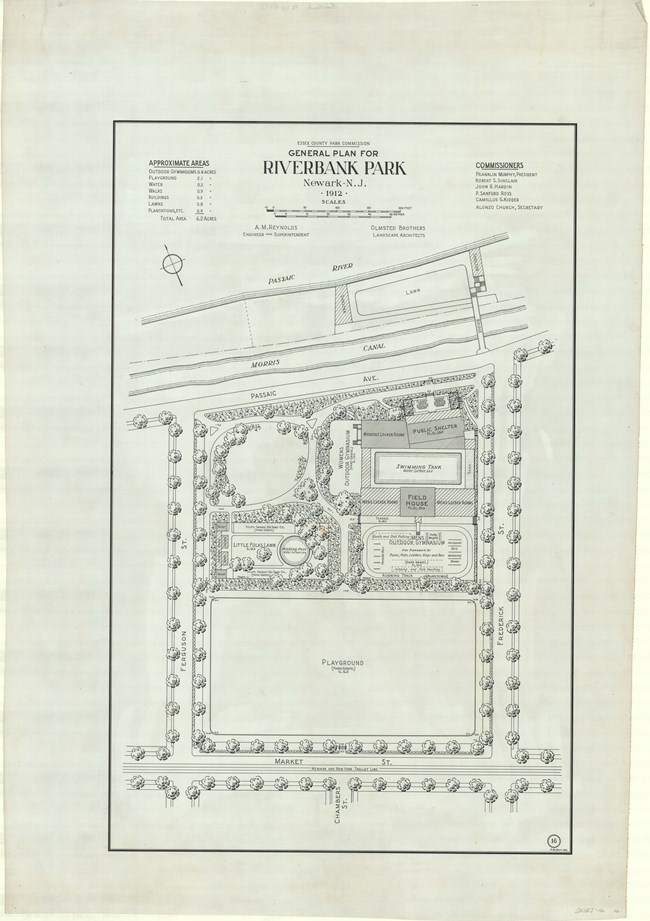

Olmsted Archives Riverbank Park (Essex County, NJ)Influenced by the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Newark, New Jersey wanted their citizens to benefit from open green spaces within congested districts where industry and residences dominate the land. Riverbank Park, designed by Olmsted Brothers, was intended as an urban park to serve the growing city. Originally six-acres, Riverbank Park is the smallest in the Essex County Park System.The main block around Riverbank Park is lined with sycamore trees along the perimeter, while Chinese elms are placed inside the park along the curved paths. Only three structures sit within Riverbank Park: the Fieldhouse, which is used as a comfort station and changing rooms, the Playground Shelter, an open-air enclosure, and the Grandstand, which provides seating for the nearby baseball field.

Olmsted Archives Harbor Park (Camden, ME)In 1928, Olmsted Brothers were hired by Mary Louise Curtis Bok to create a plan for the neglected hillside parcel of land between Camden Harbor and Camden Library. Bok likely hired Olmsted Brothers as they were currently working on subdivision and bird sanctuary in Florida for her husband. With Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. taking the lead, he was tasked with reworking the two-acres of land.To emphasize framed views, Olmsted Jr.’s design needed to employ a strategic grading plan. Curved walking paths take visitors from the street to the shore, with lush planting beds blocking views of nearby homes and stores. Olmsted Jr wanted native plants like American juniper, blueberry and lilac shrubs to flourish, many of which still do as Olmsted Jr.’s plan was carried out.

Olmsted Archives Mount Vernon Square (Baltimore, MD)In 1876, Frederick Law Olmsted was hired to redesign Mount Vernon Square in Baltimore, Maryland. Olmsted would redesign the north and south squares, while implementing similar designs for the east and west squares. Choosing to remove the cast-iron fences that encircled Mount Vernon Square, Olmsted included various pathways and grassy lawns in his design.To frame the edges of the square, low decorative stone walls were added at the entrances of Mount Vernon Square, with uniformly planted trees. Several statues of local prominent men, from Supreme Court Justices to political reformers and park proponents. To accompany the statues, fountains were added at all but the northern square.

Olmsted Archives Clifton Park (Baltimore, MD)By 1895, the Baltimore Park Commission had already begun making improvements for a public park, and already invested in the rehabilitation of green spaces throughout the city. In 1904, Olmsted Brothers submitted their first comprehensive report for Baltimore, which included reworking Clifton Park, which they saw as one of the city’s major parks that would anchor the whole system.At Clifton Park, Olmsted Brothers added recreational facilities and reorganized roadways. Their first addition was an athletic ground on the southern section of the park, with a stone wall that remains today. Also in the Olmsted Brothers’ design was a swimming pool, which, when placed, was the largest concrete swimming pool in the country. Unfortunately, a section of Clifton Park would be destroyed in 1916 to make way for a golf course, Baltimore’s first public course.

Olmsted Archives Carroll Park (Baltimore, MD)Between 1890 and 1907, Baltimore, Maryland began acquiring portions of land around the Mount Clare Estate to provide a large park for the city’s southwestern neighborhoods. In 1904, Olmsted Brothers were hired to develop a master plan for what would become Carroll Park. The plan for Carroll Park was developed to protect the historic house as well as providing grounds for passive and active recreation.Olmsted Brothers worked on Carroll Park from 1904 to 1915, and their design includes a curvilinear path system throughout the park, with the eastern section of the grounds used for active recreation while the sloping terrain near the center of the park is designed for leisurely use, with trees complimenting the existing hilltop mansion and terraces.

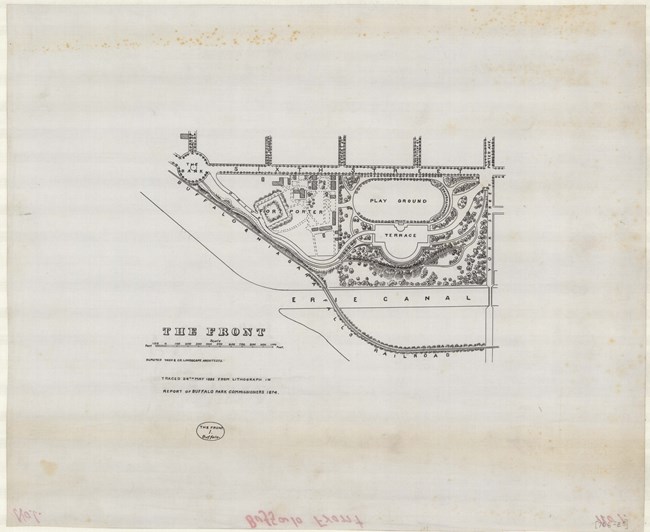

Olmsted Archives The Front (Buffalo, NY)Overlooking Lake Erie, The Front was a key part of the nation’s first park and parkway system designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux for Buffalo, New York in 1868. The most formal of the three parks linked by parkways, Olmsted saw The Front as a spot with “a character of magnificence admirably adapted to be associated with stately ceremonies, the entertainment of public guests, and other occasions of civic display.”Olmsted’s design for The Front included a playground, grassy fields for baseball and cricket, and an amphitheater, the last of which was proposed by Vaux. Next to the playground is a formal gravel space referred to as “The Terrace”, and a steep slope leads down to the Erie Canal and railroad lines. To avoid park users from seeing these, Olmsted screened them with thick plantations, and benefited from the natural difference in elevation. As with many Olmsted designed landscapes, The Front was artfully constructed to enhance nature. Extensive pathways and carriage drives provide accommodation to those walking and driving. When viewing The Front, an early Buffalo Parks Commissioner noted that “In the summer and autumn months it is fanned by a cool westerly breeze, almost constantly blowing from the lake….”

Olmsted Archives South Mountain Reservation (Essex County, NJ)In 1898, Olmsted Brothers were hired by the Essex County Park Commission to advise the group on tracts of land to purchase. One tract of land totaling more than 2,000-acres and spanning several townships and multiple jurisdictions, South Mountain Reservation, was designed by John Charles Olmsted and Percival Gallagher.Over the next few decades, more land was added, forcing Olmsted and Gallagher to erase any scars of farming, overgrazing, and timbering. At South Mountain Reservation, John Charles implemented what he called “aesthetic forestry”: assisting nature by carefully replanting healthy forested areas and underplanting the upper canopy with appropriate native trees and shrubs. Construction, forestry work, and even land acquisition continued into the 1920s, managed by Gallagher.

Olmsted Archives Grover Cleveland Park (Caldwell, NJ)In 1912, Olmsted Brothers were commissioned to develop a park for Caldwell, New Jersey, with a large portion of the park being used for both passive and active recreational purposes. John Charles Olmsted and Percival Gallagher were tasked with designing Grover Cleveland Park, with Gallagher taking a leadership role in the design process.After a visit in December of that year, Gallagher wrote to Caldwell officials and the Olmsted office in Brookline that “…general conditions for drainage are good, the soil for the most part is gravelly, and the lay of the land with reference to the sun is particularly advantageous. It is a rare piece of ground for park purposes and possesses sufficient area that can be reasonably converted into playgrounds to meet the demands for a great many years.”

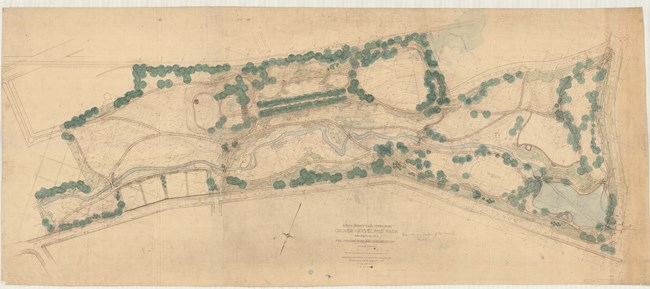

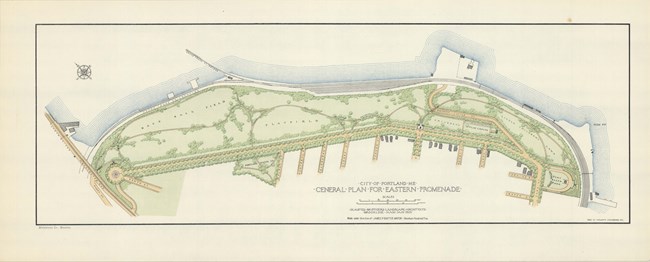

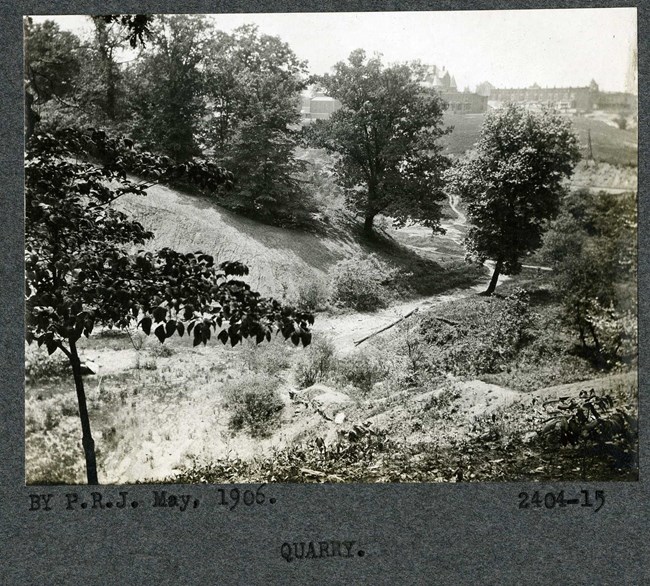

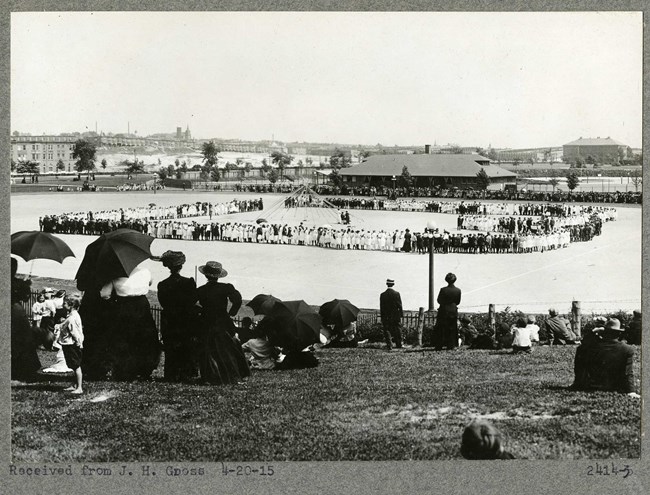

Olmsted Archives Eastern Promenade (Portland, ME)In 1905, Portland, Maine’s mayor James Baxter hired Olmsted Brothers to further develop the Eastern Promenade and create a master plan for a cohesive park system. John Charles Olmsted and Henry Hubbard took lead on design of the Eastern Promenade, proposing they follow the natural topography of the site. Their plan introduced pedestrian paths along the hillside as well as an overpass for pedestrians.Olmsted Brothers divided the Eastern Promenade into four areas: a baseball field, a play field, a children’s playground and a “Little Children’s Lawn”. Eastern Promenade focuses on active and passive recreation, as well as separate areas for different types of play and age level. Deciduous trees were planted along the Eastern Promenade to frame, not block, scenic views.

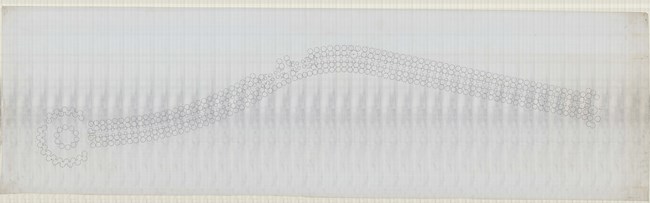

Olmsted Archives Back Cove (Portland, ME)In 1895, Olmsted, Olmsted & Eliot were hired by Portland, Maine’s mayor James Baxter to improve the site known as Back Cove. The firm proposed a dam that would form a saltwater pond, dredging the mudflats then building a tree-lined drive and promenade around the perimeter of Back Cove. While the dam was never built, ten years later the Olmsted’s would return to Back Cove, this time as Olmsted Brothers.Based on a concept in their 1905 Plan for the Portland Park System, Olmsted Brothers proposed a new design for Back Cove, but work was halted when James Baxter lost his bid for re-election. Work started up again in 1911, with Portland’s engineers tasked with stabilizing the cove’s edges, grading the roads, and constructing sidewalks and bridges.

Olmsted Archives Wyman Park (Baltimore, MD)In 1904, Olmsted Brothers prepared a report for the development of Baltimore’s Parks, including the 88-acre Wyman Park. With its old beech trees and topography, Olmsted Brothers identified Wyman Park as one of the finest single passages of scenery to be so close to a large city. Because they were so taken aback by the landscape of Wyman Park, Olmsted Brothers advocated the site becoming a stream valley reserve that would fit into the city’s grid. Within Wyman Park is the Wyman Park Dell, a 16-acre section of the park known for its steep enclosing slopes and sweeping lawn, which was fully realized and conceived by Olmsted Brothers.

Olmsted Archives Patterson Park (Baltimore, MD)Between 1905 and 1918, Olmsted Brothers developed plans for new sections of Baltimore’s Patterson Park that would lead to a 20-acre extension of relatively level land. Olmsted Brothers’ principal designs for the new section of park included active recreation facilities like a field house, swimming beach and bath house, playground, field house, and ball fields. All the facilities at Patterson Park are surrounded by curved walking paths lined with trees.

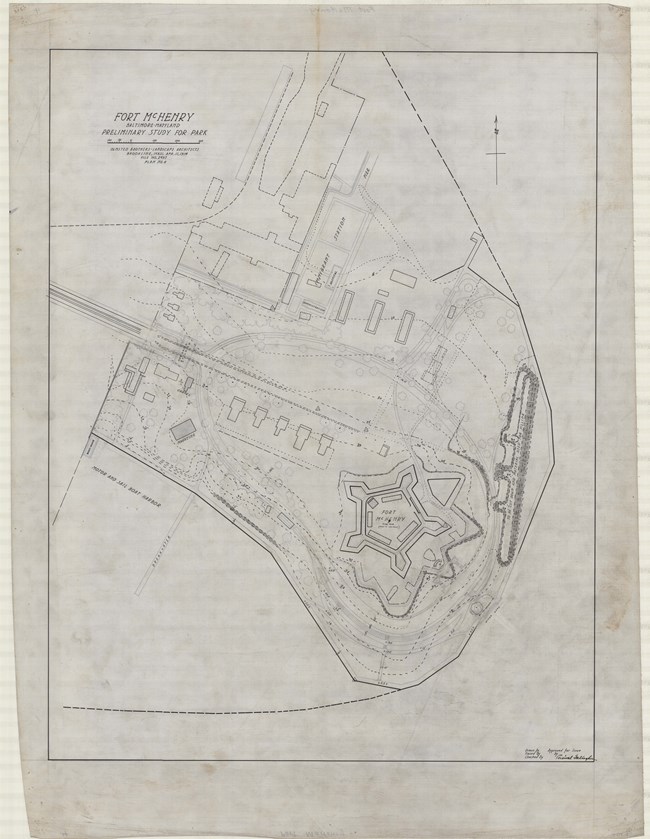

Olmsted Archives Fort McHenry (Baltimore, MD)With Frederick Law Olmsted Jr already serving on the Fine Arts Commission, it makes sense that nearby Baltimore would request an Olmsted to do work on any of their parks. In 1914, Baltimore’s then Mayor wired Olmsted Brothers for advice on preserving Fort McHenry, as the firm had already been consulting the city on municipal park matters. On April 22nd, 1914, Olmsted Jr. visited Fort McHenry and began preparing a report on the issues of the site, as well as the proposed memorial building.The focus of Olmsted Jr.’s report dealt with many of the architectural features of the park like statues and monuments. The proposed design placed memorial elements like monuments, statues, flagpoles, and the historic fort into a rigid order. A meandering circuit drive and perimeter plantings help screen off the outside world while creating open space to focus attention on the fort. Olmsted Jr. recommended removing any non-historic structures from the site to keep attention on the Fort. As a member of the Fine Arts Commission, Olmsted Jr. was placed in an uncomfortable position with the Francis Scott Key memorial. Not only did Olmsted Jr propose a design for the monument, he also passed judgement on it.

Olmsted Archives Druid Hill Park (Baltimore, MD)Druid Hill Park was originally designed by Howard Daniels, who had placed fourth in the Central Park design competition, however, as the city grew, Daniels’s design started to degrade. The Olmsted name had long been present in Baltimore, and in 1904, city officials hired Olmsted Brothers to link Druid Hill Park to newer parks in the city like Wyman and Clifton.Working on Druid Hill Park from 1904 to 1916, Olmsted Brothers’ work included entrances to the park and siting of athletic fields and playgrounds. A prominent Olmsted feature that has stood the test of time is the stone wall and fences that protects Druid Lake from automobiles. Olmsted Jr. himself would describe this solution in detail after he was asked to revisit the park after some time away.

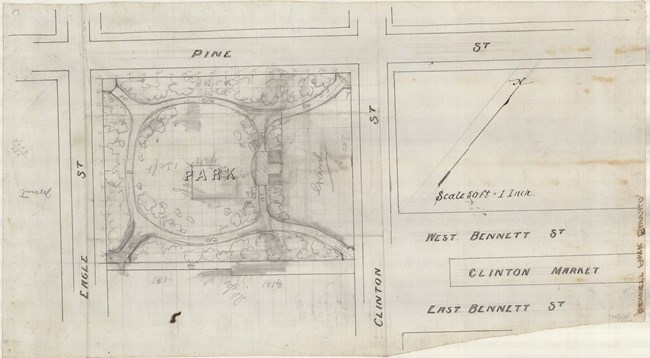

Olmsted Archives Bennett Park (Buffalo, NY)In Buffalo, which Frederick Law Olmsted described as his best planned city, the larger parks and parkways get most of the attention, while Olmsted’s designs for smaller parks, like Bennett Park, are often overlooked. In 1887, Olmsted would begin work on Bennett Park, originally called Bennett Place.Named for the property owner of the land the city had acquired, Olmsted’s design for Bennett Park called for entrances at each corner of the rectangular property, with walks encircling a horseshoe shaped open lawn at the center. In addition to a shelter and gravel playground, thick plantings screen Bennett Park from the streets, concealing from the visitor that the park is extremely small.

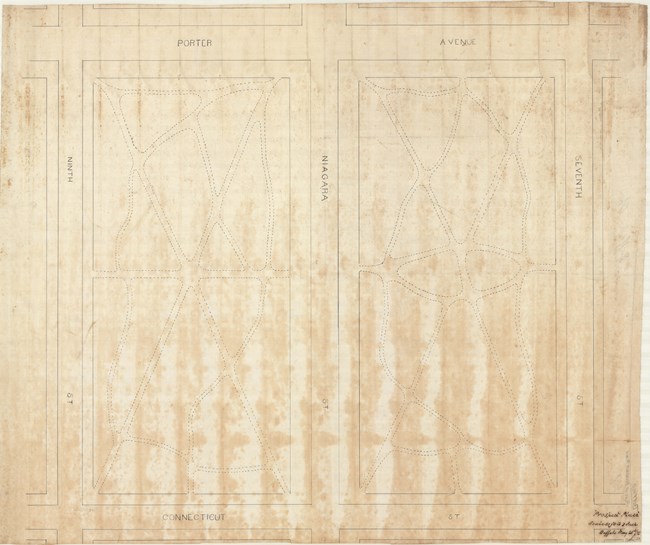

Olmsted Archives Prospect Park (Buffalo, NY)As the young city of Buffalo grew in the 1860s, Niagara Street was extended, and the new open space was known as the Prospect Hill parks, plural because Niagara Street allowed for two neighboring rectangles of greenery. By the time Olmsted arrived in Buffalo, Prospect Hill parks was surrounded by a residential community as well as a nearby reservoir. Buffalo transferred the parks to the Board of Park Commissioners, tasked with implementing Olmsted’s plan.By then, the grounds of Prospect Hill parks were populated with many mature trees and the grounds were surrounded by a fence, but no paths or other improvements had begun. Olmsted laid out walks allowing visitors to diagonally traverse the grounds without damaging them. The fences were also removed so that visitors were free to enter at any time.

Olmsted Archives Blackstone Boulevard Parkway (Providence, RI)Rhode Island’s first designed parkway, Blackstone Boulevard Parkway, was originally designed in 1886 by H.W.S. Cleveland. Before any work could be done, Cleveland would pass away, with Olmsted Brothers being commissioned to complete the design. John Charles Olmsted, with Carl Rust Parker, took lead on the design, proposing that the Boulevard’s median and shoulders should be densely planted. Although the Olmsted Brother’s design intention with their planting has diminished over time, the Boulevard has not been significantly altered.

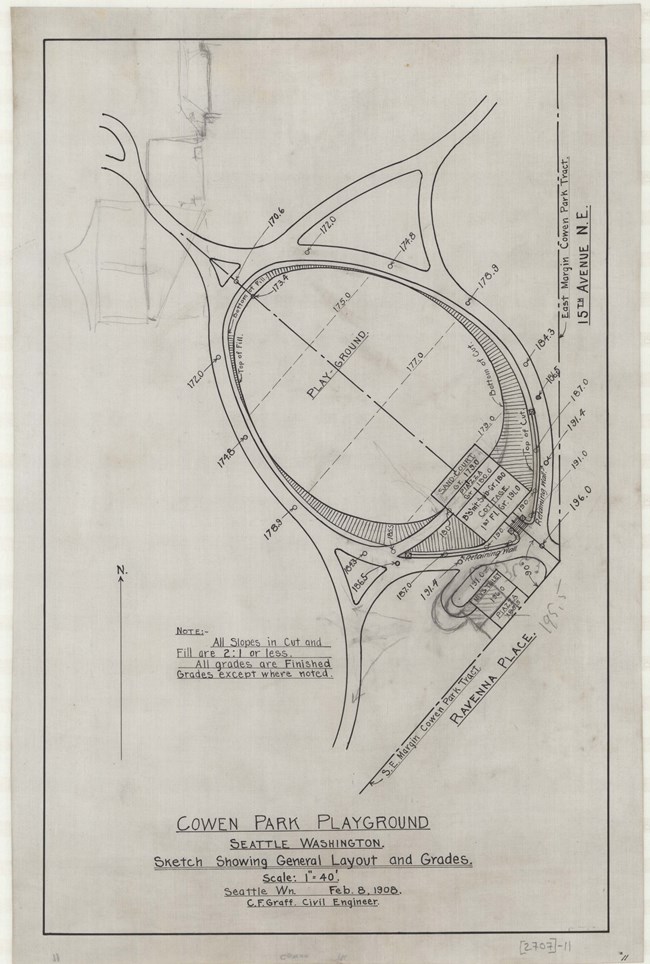

Olmsted Archives Cowen Park (Seattle, WA)In 1903, the land that would become Cowen Park was privately owned, part of the “University Park” subdivision platted by Charles Cowen. That same year, John Charles Olmsted of Olmsted Brothers recommended acquiring the land for a park. Four years later, while construction was underway on the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, Cowen donated the land to Seattle, and John Charles was asked to create a preliminary plan for a park.John Charles’ design included a “Little Children’s Lawn”, covered shelter, a plaza, four footbridges crossing the stream channel, and other small structures. At the request of the city, John Charles also designed an entrance gate for the park. Despite significant alterations due to the dumping of excess material at the park for the construction of Interstate 5, the overall shape and placement of feature’s reflects John Charles’ original design.

Olmsted Archives Lake Washington Boulevard (Seattle, WA)The longest and most significant boulevard in John Charles Olmsted’s Seattle Park System, Lake Washington Boulevard extends six miles, linking nine Olmsted Parks together. First proposed in Olmsted Brothers’ 1903 report, they recommended the Boulevard stretch beyond Seattle’s limits towards water.John Charles observed that a nearby street “is laid out on a succession of straight lines, . . . resulting in an extremely ugly route for a pleasure drive, and this street is apparently pushed out so close to the water line, and in some cases even beyond it, that scarcely a single one of all the beautiful trees which now fringe the lake, not to mention the important undergrowth, could be preserved. It would scarcely be possible to solve the problem in a more hideous manner than has been done in this case.” During the planning stages of the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, Lake Washington Boulevard was intended to serve as the vehicular entry to the Exposition grounds, showcasing the beauty of Seattle’s scenery along Lake Washington.

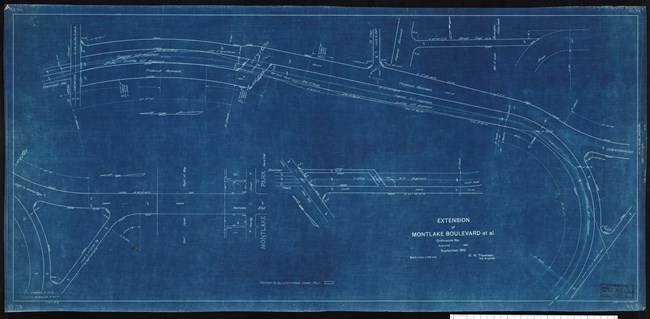

Olmsted Archives Montlake Boulevard (Seattle, WA)Originally called University Boulevard, Montlake Boulevard was designed by John Charles Olmsted after writing up a series of recommendations in 1909 for the University of Washington. The Boulevard first served as the grand automobile entrance for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition, with John Charles hoping that the Boulevard would continue by the water’s shore, instead of cutting through a residential neighborhood.At Montlake boulevard, John Charles’ design called for cement sidewalks and trees separating those sidewalks from the street. For trees he suggested four rows of tall Tulip trees in line with the trolley polls. He envisioned the streetcar tracks would be set into the turf of the central "parking strip."

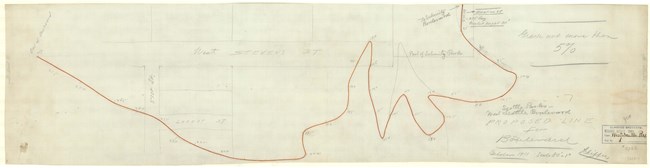

Olmsted Archives West Seattle Parkway (Seattle, WA)Recommended in Olmsted Brothers 1908 report on Seattle’s parks, West Seattle Parkway was one of several thought-up by John Charles Olmsted never to be built. By 1911, it seemed work at West Seattle Parkway would pick up, with John Charles recommending a refined alignment to address topographical challenges by utilizing sharp turns that would lead to an elevated bridge. The topographical challenges at West Seattle Parkway rivaled those along Lake Washington Boulevard.

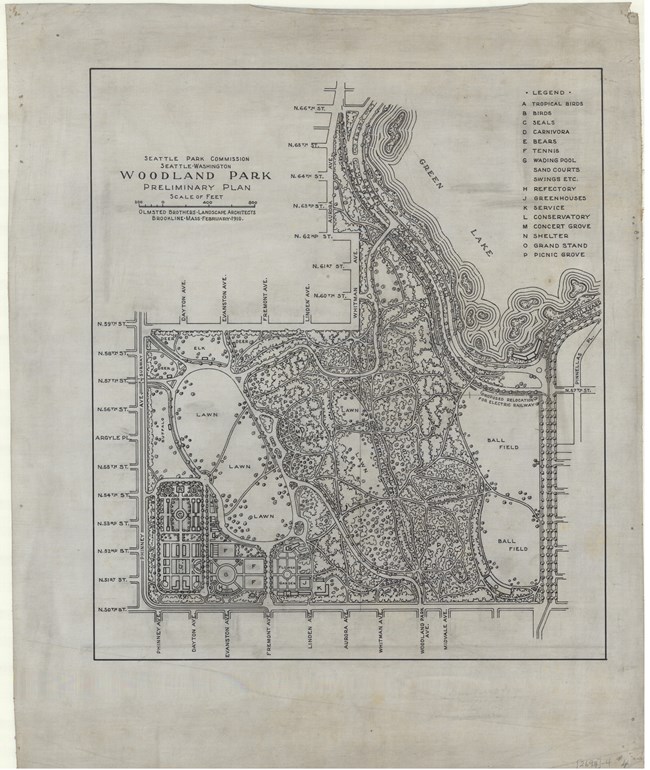

Olmsted Archives Woodland Park (Seattle, WA)In 1889, Seattle entrepreneur Guy Phinney purchased 179-acres for the development of a commercial park. It would take another fourteen years for Olmsted Brothers to be hired and begin designing Woodland Park, which would be the city’s largest. With John Charles Olmsted taking the lead, he prepared his first report for Woodland Park, suggesting one section be reserved for a zoo, and the other retained for passive and active recreation.In 1908, John Charles created a new plan for Woodland Park and the zoo, with the Great Lawn serving as its focal point. With zoo buildings arranged next to formal gardens, a playground, wading pool, and tennis courts were placed along the Great Lawn’s boundary. Believing native forests are vital to urban areas, John Charles preserved the area’s natural woods, and enhanced them through a network of trails.

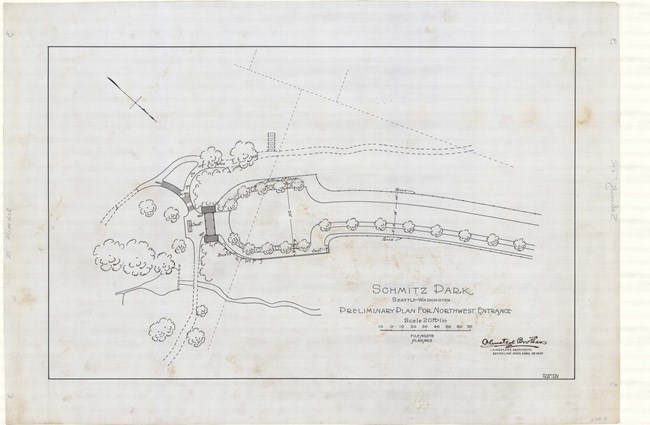

Olmsted Archives Schmitz Park (Seattle, WA)Originally known as Forest Park, Olmsted Brothers described the area in their 1908 Plan for Seattle Parks as “a densely wooded ravine…valuable for its scenic effects, and for recreation purposes.” Between 1908 and 1912, what would become Schmitz Park was donated to the city in pieces, with the largest chunk coming from Ferdinand Schmitz, a German banker who served on the Park Commission. Schmitz donated his land “to be used perpetually…for park purposes…in order that certain natural features be preserved. |

Last updated: June 26, 2024