Viewpoint

Changeable Degrees of Authenticity(1)

by David G. DeLong

Authenticity can be a troubling term, and the quest to identify the real thing is always difficult. Some even question whether the cause itself is valid. For example, the scholarly author of a recent article in the New York Times Magazine claimed that aspects of "modernity" and "contamination" could better support social values than "preservation" and "authenticity." He argued that an ideal of a single, definable "authenticity" limits the cosmopolitanism of choice, that any absolute decree of authenticity is a kind of cultural totalitarianism limiting choice and suppressing pluralism.(2)

At best, determining what is authentic can be troubling, even when dealing with the deceptively simple issue of original fabric in historic buildings. Folklorist Regina Bendix may have come closest to exposing this problem when she wrote that "the search for authenticity is fundamentally an emotional and moral quest."(3) Lionel Trilling, in considering aspects of literary and artistic authenticity more than 30 years ago, similarly called authenticity a "strenuous moral experience." Trilling added that authenticity is one of those words, like irony or love, "which are best not talked about if they are to retain any force of meaning."(4)

This, of course, has had no effect. People seem to be talking about authenticity more than ever. Has the term "authenticity," like the terms "style" and "heritage," become so widespread and so loosely applied that it is debased and no longer of use? Probably not, but it desperately needs scrutiny because, with the proper focus, the determination of authenticity can provide a needed lens for the evaluation of preservation efforts.

Literal versus Conceptual Authenticity

This essay identifies several degrees of authenticity in the preservation of buildings that this author has found personally helpful in sorting out the problem.(5) Literal authenticity—what many would consider the most traditional and authoritative form of building authenticity—can be illustrated by an International Center for Conservation in Rome (ICCROM) project consolidating a 16th-century scrafito façade in Rome. This technique of a dark undercoat with overlapping whitewash, which is scratched back to create patterns, is a lost tradition. It was thus critical to retain the original material wherever possible, although missing areas of scrafito disrupted the perception of the wall as a totality. A grouting of lime and brick dust was injected behind to consolidate the surface, which was then cleaned to remove the dirt. Small lacunae were recreated through retouching. In areas with large lacunae, a neutral render was applied (even though the repeating pattern was known). In this way, as in paintings, the disturbance is left, but made less obvious. The residue of old window frames was also left, treated with a neutral render. Thus, in a time-honored approach, changes over time are allowed to read but are not intrusive. In accord with theories developed by Cesare Brandi, the aesthetic unity has been regained without falsification. As Brandi has written, "restoration must aim to reestablish the potential unity of the work of art, as long as this is possible without producing an artistic or historical forgery and without erasing every trace of the passage of time left on the work of art."(6)

Conceptual authenticity can be illustrated by another ICCROM example dealing with a 1732 theater façade on the island of Malta. In 1928, it had been converted to a movie theater, then after World War II converted back to a theater. During these changes the façade had weathered badly and disruptive elements, including light sconces and pipes, had been added. Unlike the Roman scrafito example the limestone façade represented a local building tradition that had continued unbroken into the present. It was decided to use local materials and masons to replace or patch damaged stones. To unify the façade, a colored lime wash, also part of the Maltese building tradition, was applied. Thus this theater is an example of conceptual authenticity in that the material is not all original, but the original concept has been regained and aesthetic unity has been reestablished.

Degrees of Authenticity at Fallingwater

How might these approaches be reflected in more current American examples, and what other variations complicate the picture? Considering several buildings by Frank Lloyd Wright serves to further explain the degrees of authenticity within a limited set of variables. Fallingwater, Wright's masterpiece near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (built 1935-1937), provides a complex example of literal authenticity. As a work of modern architecture its elements parallel attributes used to authenticate paintings: Wright was fully in charge of its design and gave it his full attention; it was realized without compromise, honoring Wright's concept; through visits, Wright's hand documented the object itself; its provenance is clear; and it was continuously maintained by its original owners with no significant changes.(7)

The Kaufmanns regarded themselves as stewards of a major work of art. Edgar Kaufmann Jr., gave Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy with the clear understanding that it was to be preserved as a great work of modern architecture. The Kaufmann family was not to be a feature of the interpretative program, and traces of family occupation were not to be sentimentally retained. Kaufmann also hoped that it could be perceived as a house rather than as a museum, with people able to walk on the rugs and sit on the sofas.

The structural daring of Fallingwater has complicated its preservation. From the beginning, workers were afraid to remove the scaffolding until Wright himself offered to join them beneath the cantilevered slab. Indeed, it deflected almost instantly, and a little more than Wright had predicted. The suspended stair was less problematic, but during annual spring floods floating branches tended to catch behind it and twist it out of shape. In the end, ties were added at the base to hold the stair in place. There have been structural collapses, most notably when a tree fell against the cantilevered trellis. During repairs, it was noted that some of the concrete had been so poorly mixed that it had reverted to sand and gravel.

A far more serious and overly sensationalized problem became apparent a few years ago. The major slabs had deflected further; inspection revealed that steel reinforcement had been wrongly placed by local workers unfamiliar with such daring construction. Also, more steel probably should have been used from the beginning. After studying the problem, structural engineer Robert Sillman reported the grim news that, according to the most advanced structural calculations, Fallingwater could not stand. Wright's intuitional sense of structure defied logic. Sillman said it might survive forever, or it might collapse at any moment. The cantilevered terraces were immediately closed until a solution could be found.

One member of the Fallingwater advisory committee suggested tearing it down and rebuilding it, thus sacrificing all literal authenticity. Another committee member suggested that temporary supports propping up the slab be left forever as a record of the problem. This second suggestion, of course, would have seriously compromised the aesthetic unity of the building.(8)

In the end, the committee supported Sillman's recommendation to thread steel cables through hollow tubes connected to the sides of the beams; these were then post-tensioned to stabilize the slab, much in the manner of a splint along a broken bone. No attempt was made to lift the sagging terraces as their deflection was a visible manifestation of the building's age and an indication of technological limits encountered in its building. More pragmatically, if the slabs had been lifted most of the windows probably would have cracked.

Literal authenticity was compromised, but without sacrifice of original material and with full retention of aesthetic unity. Exterior and interior finishes remained as originally applied; nothing of the original structure was removed or replaced. The new cables can be clearly identified as added reinforcement by anyone who inspects the interior workings of the building. Modestly contrasting plaster plugs along the front of the building identify their location and also provide, at close range, a visible record of modification without compromising artistic integrity.

Conceptual Authenticity at Auldbrass Plantation

Conceptual authenticity presents problems of a different sort: It is a more perilous route of preservation, yet one gaining acceptance particularly when dealing with buildings of the recent past. Some have suggested that given the largely conceptual nature of much modern architecture, authenticity of design might well receive priority over authenticity of material.(9) One might argue that modern architecture is no more conceptual than Italian Renaissance or Neo-Palladianism, to name only two highly conceptual periods in architecture. But such conceptual authenticity can work best for those modern buildings where the original designer's intentions are clearly and fully documented, and original materials and building technologies are available to realize those intentions fully.

Wright's Auldbrass Plantation near Charleston, South Carolina, provides a compelling case study in conceptual authenticity. It was commissioned in 1938 by Leigh Stevens, an industrial consultant who wanted Wright to envision a southern plantation appropriate for the 20th century. Wright's design eliminated all references to formal symmetry that had been traditional in plantations, instead conceiving a continuous, screen-like enclosure about multiple axes. He envisioned two interconnected lines of low, angled buildings with the main house and guest house along the edge of a lake, and farm buildings and related structures arranged opposite. The main house was relatively small in scale and low in profile, subservient to its supporting buildings. Workers' cottages were located a distance away. Wright invented a unique, angled wall system that he used throughout. The result was a light, permeable enclosure without exact parallel. Construction began in 1940, but work was far from smooth or continuous, complicating evaluations of authenticity. By December 1941, construction was sufficiently advanced to excite local interest. An article in the Charleston News and Courier ridiculed the place as an "angled crazy house." Stevens forbade any further visitation, and for many years the plantation was never published.

There were many problems with construction such as angles and roof heights that did not quite meet and insufficiently cured cypress that twisted out of shape. Wright did not visit the site until several years after construction had begun, thus construction was not documented by the architect. On-site supervision by one of his inexperienced apprentices was weak. Insensitive changes by the client—such as reconfiguring the toilets and reassigning rooms—further compromised Wright's vision. Soon after the outbreak of World War II, construction halted, leaving the plantation unfinished.

When construction resumed after the war, Stevens's new wife made disfiguring changes like painting the exposed brick surfaces, adding drapes and heavily upholstered furniture, and enclosing a covered portico to create a kitchen more to her liking. Her desire for a house of pastel, genteel charm was totally at odds with the rustic lodge Stevens and Wright envisioned. Stevens hated what she did and eventually divorced her, but the changes remained. In March 1952, the barn, chicken coops, and cattle barns burned, and Stevens could not afford to replace them.

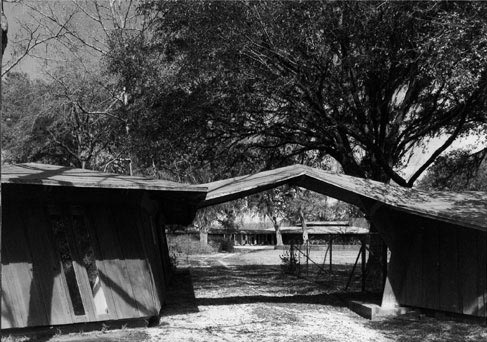

By 1987, Auldbrass Plantation had fallen into a ruinous, abandoned state.(Figure 1) It would not have survived more than a couple of years without drastic intervention, and it had little, if any, meaning as an abandoned shell. Around this time the property was bought by the Hollywood producer Joel Silver, who embarked upon an ambitious and thorough research campaign with the goal of realizing Wright's original concept. Buildings destroyed by the 1952 fire were rebuilt by following the original working drawings. To record their more recent date, a slightly different species of cypress was used, with a different grain, achieving something in the manner of a stippled infill.

|

Figure 1. This view, taken about 1979, shows Auldbrass Plantation in South Carolina in a deteriorated state. (Courtesy of Joe Silver.) |

Other buildings were restored, retaining original materials where possible, so parts of the complex reflect a literal authenticity. But the dominating impression is one of conceptual authenticity, for certain significant elements that Wright had envisioned but that had never been built were now realized. Thus, the driveways were at last lined with the defining edges that Wright wanted; they were essential to his vision of unified components. The pool, never realized, was built as originally designed.

Copper roofs that Wright had originally planned were installed, replacing a shapeless mass of substitute roofing material. With the correct roofs in place, the crisp linearity of Wright's design emerged. The original copper designs for leaders at the tips of the broad overhangs were fabricated for the first time and replaced the wood substitutes and conventional downspouts that had marred the structural clarity of the house. Furniture and air conditioning units added by Stevens's wife were removed and original furniture refurbished, or new furniture rebuilt, according to Wright's original drawings and specifications. A dining room designed by Wright in 1953 was at last added within the breeze way linking the main house and original kitchen.

The plantation was thus restored to a state of completion that had never existed before—somewhat in the manner famously advocated by the 19th-century French architect and restorer Viollet-le-Duc.(Figure 2) The design as a work of art was captured, taking us to the very edge of, and perhaps just over, the ethical limits of conceptual authenticity. By no means is this preservation in the conventional sense. But in this particular instance, with Wright's design fully documented, with original materials and building technologies still part of an ongoing tradition, and with eye-witnesses to the original buildings, it seems justifiable.

|

Figure 2. This view, taken around 2001, shows Auldbrass Plantation as restored. (Anthony Peres, photographer.) |

Authenticity at Other Frank Lloyd Wright Sites

One very real risk is that in the name of such conceptual authenticity, serious mistakes will be rationalized. Work on the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City provides one possible example. There is no question that Wright's original concept called for a seamless continuity of exterior surfaces. Given the technological limitations of the 1950s, this was not possible. Under Wright's direction, a vinyl plastic paint was applied to the exterior surface. This exterior coating helped conceal underlying cracks and flaws but did not totally hide them. The building as completed thus reflects a noble struggle and brings into sharper focus Wright's structural daring.

Some people at the museum would like to get rid of these surface imperfections and achieve the complete continuity Wright first imagined. Synthetic, shell-like encasements that would achieve this are now available and would produce the desired result. At first, this possibility seems very attractive but on further thought reveals a major flaw. Conceptual authenticity—when it is risked—should be framed within the technological limits of the building's original era. Unlike Fallingwater, where a clearly differentiated structural bracing was placed within the building and had no visible effect, here the retrofit would significantly change the appearance of the building itself. Had such a coating been available when Wright designed the building, his concept might well have been different. Arguably the most appropriate option would be re-treating the original surface with a similar paint, leaving the original's patina of flaws as a record of the fallibility of its concrete and a demonstration of Wright's refusal to be bound by conventional limits of technology.

Resolving issues of literal versus conceptual authenticity can often lead to conflicts, as in the restoration of the Darwin D. Martin House in Buffalo, New York, one of Wright's early masterpieces. Disfiguring changes made to accommodate Mrs. Martin's special needs in her later years had compromised the building's integrity. One group of advisors argued that the literal authenticity of these changes should be retained as the record of a design error. But surely the artistic integrity of the design is of greater significance than the physical challenges Martin encountered in her later years. Indeed, the alterations have been removed, and conceptual authenticity recaptured.

Another degree of authenticity is surface authenticity, a drastic approach that sometimes can be justified to save great structures. For example, the temples at Abu Simbel were relocated to escape the waters of the Aswan Dam, and Borobudur, the great Buddhist temple in Indonesia, was restabilized with an inner concrete frame of considerable girth to keep it from sliding down the hill.

Wright's Freeman House in Los Angeles shows the often problematic nature of a restoration conducted according to principles of surface authenticity. Wright's California block houses of the early 1920s were ravishing as designs, but failures in terms of their experimental technology. The blocks have leaked and disintegrated, and the structural underpinnings have in some cases worn away. At the Freeman House a complicated, massive concrete frame will replace the original wall-bearing structure. This is deemed necessary to preserve the exterior appearance of the original design. The blocks themselves will need to be removed and reattached or replaced if damaged beyond repair. What will be lost is the fragility of Wright's original structure. In the case of so simple and small a house, the new and mighty structural retrofit might be an instance of overkill. The house will be saved, but what was once structural will have been transformed into decorative sheathing.

Another degree of authenticity—fragmented authenticity—can be illustrated by Wright's Little House in Minnesota, which was dismantled and its parts shipped off to various museums. The Metropolitan Museum of Art received the main living room and reinstalled it, but with necessarily compromised results. Experiencing the totality of his designs is essential to understanding Wright. That is not possible with such a fragment, however expert its re-installation, and however original its component parts.

Such fragmentary authenticity could be said to work in certain very restricted situations, such as with the office Wright designed for Edgar Kaufmann, Sr. Here the concept itself was of a fragment, a series of screen-like elements installed within the Kaufmann department store. As with Fallingwater, Wright gave the design full attention: It was realized as he envisioned, and the provenance remained clear. When the store was sold, the office was carefully recorded, dismantled, and put in storage until an appropriate setting could be found. In this case, it has made a more believable transition to a museum setting at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Conceptual Authenticity?

Different degrees of authenticity at one site can be illustrated at Sardis, an archeological site in Turkey on which I worked in the late 1960s. The Hellenistic temple of Artemis reflects literal authenticity, as one would expect at an archeological site. It was excavated, with most stones left where they had fallen. Nearby, at an early-3rd-century marble court, a grand forecourt to a vast Roman bath, fragments were fitted together in the field like a giant puzzle. When new column capitals were needed to complete the aedicula, they were hand carved in a traditional manner but with the acanthus leaves left unveined as an architectural stipple. Column bases had been found in situ, and the location of each piece of the fallen frieze could be determined by the dedicatory inscription. The reconstruction of the lower story was a matter of surface authenticity, as a new reinforced concrete frame had been built behind the pavilions to provide needed support.

One of my roles at the site was to create a conjectural restoration of the second story. Plenty of parts existed, but many of them failed to match. There was a mixture of square and round column shafts, for example, that had been excavated from the site. I was asked to use them all, although it seemed that some might have been dragged there from other locations in preparation for feeding them to an adjacent lime kiln that was set up after the city had been abandoned. The resulting solution was highly speculative but managed to use all the pieces. I expected the actual restoration to stop with the first floor.

Upon returning to the site several years later, I was astounded to see the second story built. The result could be termed conjecturally authentic, as it was based on carefully studied archeological evidence but without firm knowledge of the actual details. It serves a valid didactic purpose but should not be considered authentic in any conventional sense. Some would simply call it inauthentic, but even that term raises troubling issues, such as the claim that everything is authentic in some way.

Is it necessary to be so accommodating in historic preservation? Hopefully not, otherwise we are left with what Alexander Pope (1688-1744) wrote in 1733: "one truth is clear, whatever is, is right."(10)

About the Author

David G. DeLong is emeritus professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania where he was chair of the graduate program in historic preservation from 1984 to 1997.

Notes

1. This essay is based on an address presented at the Fifth National Forum on Historic Preservation Practice, "A Critical Look at Authenticity and Historic Preservation," March 23-25, 2006, at Goucher College, Baltimore, Maryland.

2. Kwame Anthony Appiah, "Toward a New Cosmopolitanism," New York Times Magazine (January 1, 2006): 30-37, 52. Appiah is a native of Ghana who teaches at Princeton University.

3. Regina Bendix, In Search of Authenticity: The Formation of Folklore Studies (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1997), 7.

4. Lionel Trilling, Sincerity and Authenticity (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), 11, 120.

5. I will not attempt to deal with cultural landscapes or historic districts. I am grateful to Jeanne Marie Teutonico—now the associate director of the Getty Conservation Institute—for sharing her earlier work at ICCROM with me.

6. Cesare Brandi, "Theory of Restoration I," in Historical and Philosophical Issues in the Conservation of Cultural Heritage, ed. Nicholas Stanley Price, M. Kirby Talley Jr., and Alessandra Melucco Vaccaro (Los Angeles, CA: The Getty Conservation Institute, 1996), 230-235, 231.

7. These attributes of authenticity, which I have adapted from those applied to painting, have been outlined by Charles Rhyne, a professor at Reed College who has authenticated paintings for major museums. See Charles S. Rhyne, "Deaccessioning John Constable: The Complexity of Authenticity," paper presented in the session Authenticity in Art History at the Annual Meeting of the College Art Association, New York City, February 17, 1994; available online at http://www.reed.edu/~crhyne/papers/deaccessioning.html, accessed on May 2, 2008. I am grateful to Professor Rhyne for bringing this paper to my attention.

8. Edgar Kaufmann Jr., asked that after his death the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy establish an advisory committee to help oversee the preservation and interpretation of Fallingwater. He named those he wished to serve as charter members, including the author.

9. For example see Alan Powers, "Style or Substance: What are We Trying to Conserve?" in Architecture, ed. Susan Macdonald (Shaftesbury, Dorset, England: Donhead, 2001), 3-11.

10. Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man (1733), Epistle I, Stanza X.