Exhibit Review

George Washington Carver

The Field Museum, Chicago Illinois; Organized by The Field Museum in collaboration with Tuskegee University and the National Park Service; Michael Dillon, Curator; Hilary Hansen, Project Manager

February 1 to July 6, 2008 and traveling

"I am a dreamer who dreams, sees visions, and listens always to the still, small voice. I am the trail blazer." —George Washington Carver |

A visitor who knows only a little about George Washington Carver's life before coming to this exhibition will have the experience of looking up from a single cotton boll to the white-flecked sea of a cotton field. Carver led a rich life, and this exhibition does justice to its drama and complexity. Over the course of an hour or so, visitors who thought of Carver as "the peanut man"—as did many of his contemporaries—discover he was a teacher and researcher whose natural curiosity and humanitarianism set an example that has inspired generations.

A two-minute video introduces the exhibition by sketching the highlights of Carver's extraordinary life, whetting the appetite for the material to come. Historic photographs and original artifacts capture the story of his dramatic infancy, telling how young George was born a slave in 1864, brought to death's door by whooping cough, kidnapped, orphaned, and emancipated before he was a year old. A diorama of the Missouri farm where Carver grew up and samples of his childhood hobbies of sketching and fossil-collecting help visitors imagine him running through the fields of the rural south, awakening to a love of nature that lasted his whole life. One of the most remarkable artifacts on display is a linen tablecloth embroidered with delicate tulips, a product of Carver's hands: Weakened by disease, he learned sewing, knitting, and embroidery to help around the house.

The exhibit also tells the story of Carver's 20-year struggle for higher education. Having outgrown several local and regional high schools, Carver sought education at three different colleges. The first college that accepted him turned him away when it discovered he was black. At the second, Simpson College in Indianola, Indiana, Carver's teachers encouraged him to pursue the arts. Examples of his sketches illustrate why their recommendations were so strong. However, Carver decided that he wanted to help poor black farmers and that a degree in agriculture would serve him best. He graduated from Iowa State College in 1896.

|

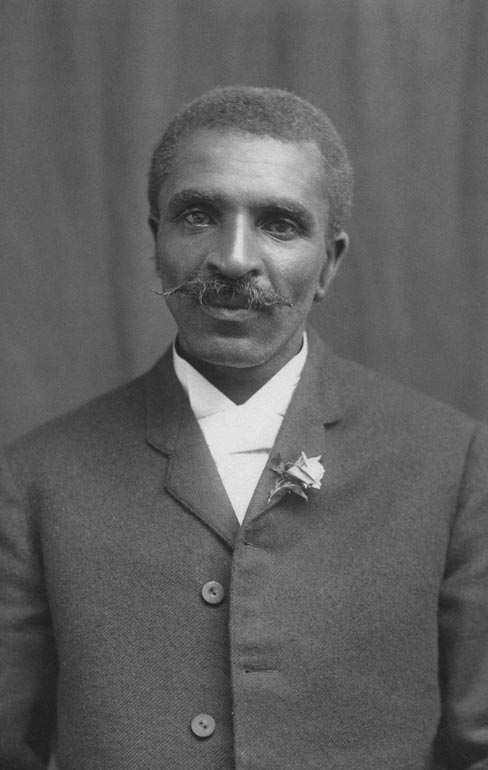

Figure 1. A visionary scientist, George Washington Carver, shown here in this undated portrait, has inspired generations. (Courtesy of the Tuskegee University Archives and Museum.) |

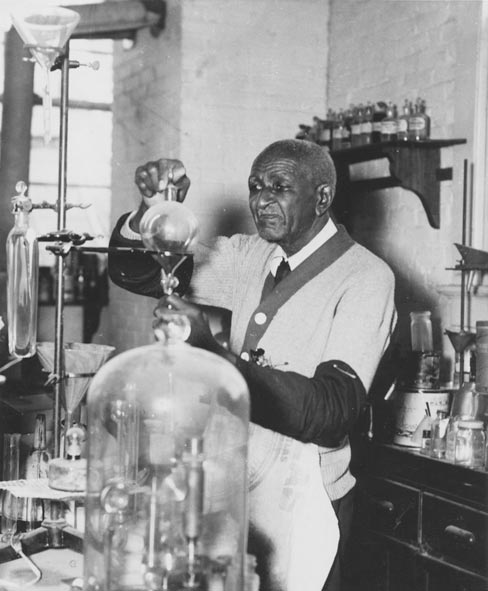

Carver's contributions to the scientific field formerly known as "chemurgy," which entailed the production of industrial products from agricultural materials, were largely made during his tenure at Tuskegee University in Alabama. The handmade lab equipment on display in the exhibition is a testament to the stark conditions at the university when Booker T. Washington invited Carver to head the school's agriculture department. Carver and his students conducted research and experimented with different types of crops and crop rotation in their quest to improve soil quality.

The exhibit does a good job of placing Carver's work within the context of Reconstruction in the South after the Civil War. Cotton was in some ways Carver's enemy: It fueled the economy that had fueled slavery; it drained the southern soil of vital nutrients; and it trapped poor black sharecroppers into grueling poverty. King Cotton, once the great cash crop, was scarcely profitable when Carver came to Alabama. Knowing that planting nitrogen-fixing plants could restore the soil, Carver encouraged farmers to rotate their cotton crops with peanuts, soybeans, and sweet potatoes, increasing their yield and contributing to better soil quality overall.

Learning about Carver's research was interesting, but learning how he spread that knowledge to help impoverished black farmers was one of the most fascinating parts of the exhibition. In 1906, Carver designed a mobile educational laboratory called the Jessup Wagon, named after its financial backer, Morris K. Jessup. The exhibit includes a full-scale reproduction of the wagon on which visitors can find examples of the demonstrations Carver did as he traveled around Alabama. Nearby are two good interactive presentations that illustrate two lessons: how to improve soil quality and how to re-use materials to beautify a homestead. The interactives are short, attractive, clear, and fun.

Though not overtly discussed in the exhibit, one theme that becomes clear is that throughout his life, Carver was in situations where he was considered something of an outsider. Orphaned before he was a year old, Carver lived with his former owners and took their last name, but it is unclear whether they considered him more of a son or an indentured servant. At Simpson College, Carver was the only black man on campus and, while encouraged, was always something of an anomaly. At Tuskegee, he encountered racial tension from his black colleagues, who disdained what they considered to be his Northern affectations and need for "special treatment." As a result, Carver spent more social time with his white colleagues there.

The penultimate section of the exhibition focuses on the products Carver developed to make his three soil-restoring crops more profitable for the farmers who grew them and the lab equipment he used to create them. Though it is the most conventional part of the exhibit, consisting of beakers and jars in glass cases, it is the section that best presents Carver's ingenuity. Visitors are asked the question, "Guess which plant is used to make all of these: molasses, ink, vinegar, flour, library paste, shoe blacking, alcohol, dyes, hog feed, after-dinner mints, candy, and yeast." The answer? The sweet potato.

Equally fascinating is an audio interactive that allows visitors to hear Carver's voice as he responds to a reporter's question, "Do you consider yourself a chemist?" In his high, thin voice shaped by childhood disease and age, Carver says that he uses the laboratory to find things he is looking for, that it "is simply a place where we tear things to pieces." Here, we understand that Carver is just a curious man, wanting to know more about the world. This curiosity, this humility, and also an abiding faith are expressed in samples of his correspondence on display.

|

Figure 3. Shown here in his laboratory, Carver wanted to do great things for people, not solely for academic science. (Courtesy of the Tuskegee University Archives and Museum.) |

The end of the exhibit follows Carver's growing fame in his lifetime and his legacy. Magazine articles illustrate how he became famous as "the peanut man" after testifying before the U.S. Congress about the potential uses of peanuts during a debate over a proposed protective tariff for the crop. The caricature of him as the father of peanut butter (which, incidentally, he did not invent; it predated him) started at that time, when the press and public lauded him as a black hero whose humility and focus on economic improvements rather than social struggle made him palatable to whites nationwide.

Finally, the exhibit puts Carver's work into the context of our current resurgence of research into natural products. Chemurgy was overpowered by petroleum in the decades after Carver's work, but it is experiencing a revival through the New Uses Council developed in 1990 to promote research and development of new products from natural sources. A display of some of these recent discoveries includes soy-based newspaper ink, soy fiber stuffed animals, and a biodegradable plastic water bottle.

Although not intended for children, the text and materials are accessible for young adults.

The exhibit has a corresponding website—http://www.fieldmuseum.org/carver/index.html—that includes highlights from the exhibit and an extensive educator's guide. The exhibit will travel through 2010. The schedule is available online at http://www.fieldmuseum.org/exhibits/traveling_carver2.htm.

Sarah Arehart

University of Chicago