Research Report

Adaptive Re-Use of the Old Evangelical English Hospital in the Town of Salt

by Jawdat S. Goussous

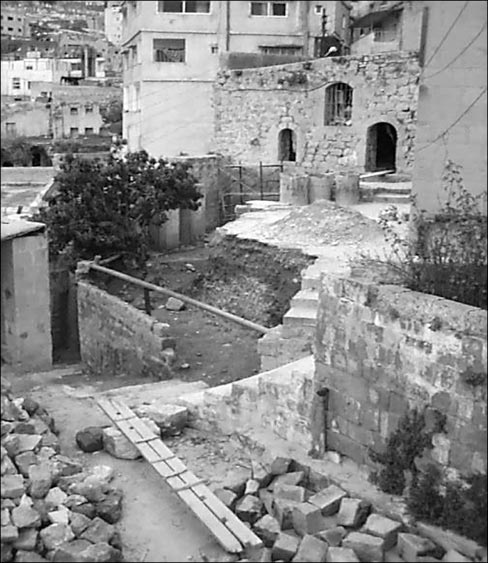

Although the conservation of urban areas, buildings, and historic monuments of architectural value has been a major preoccupation of architects for many years, the field of architectural conservation is relatively new to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. There is a growing awareness, however, of the need to protect cultural heritage and preserve the historic architectural and urban identify of this Middle Eastern nation. An example of this new focus is the ongoing stabilization and re-use of the Old Evangelical English Hospital nestled in a northern hillside of the Saaha above the Anglican Church in the town of Salt, 30 kilometers southwest of Amman, Jordan's capital and largest city.(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1. The Old English Hospital complex in the city of Salt is a prominant urban landmark. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Construction of the hospital began in the 1890s and continued up until 1926. It was damaged a year later in an earthquake, and hospital care eventually moved to the As-Salalem area of Salt in 1935. As built, the English Hospital has simple semi-circular and segmental openings in the facades. All rooms open onto a veranda overlooking the plaza.

The English Hospital was part of an extensive Anglican mission complex. Residents of Salt had asked the Anglican Church in Jerusalem for a church and school. Formal religious services took place for the first time in 1849, and the Bishops School gradually grew to include approximately 400 students. In 1866, Bishop Gobath acquired property in the center of Salt for a clinic and church in the town. Work on a mission house began around 1870 and on a church shortly thereafter. The Church Missionary Society (CMS) assumed responsibility for the project in 1873 and began providing medical services on-site in the 1880s. The term, "hospital," was attached to the site sometime afterwards.

This first hospital in Jordan began with simple facilities. In 1889, work began on the ground floor of the current structure and soon expanded to include a second floor and other buildings, notably a caretaker's house and mission dispensary. Records from the late 19th century show that patients included Bedouin from as far away as Morocco and Yemen. World War I and the Turkish occupation of the area temporarily disrupted the hospital's activities. His Majesty King Abdullah bin Hussein, King of Jordan, dedicated an enlarged and renovated hospital facility in 1922.

Certain features of the complex are of particular importance architecturally. The organization of the different spaces and functions around the open courtyards and the solid-void relationship are both significant. Attractive landscape features survive on the upper terrace. The verandas of the English Hospital and the huge retaining wall that carries them are unique in Salt. The stonework, interior details, and the bell towers of the church combine to make this a distinguished building. Moreover, the building styles of the different stages of the complex reflect the characters of their respective periods.

Over time, dampness, mold, theft, vandalism, and misuse, along with the construction of larger and taller buildings in the Saaha, such as the great Mosque and the Quteishat building in front of Abu Jabber House compromised the integrity of the mission complex. In the case of the Anglican Church and Sunday School, an insensitive renovation compromised important features, notably the buildings' stone tiles.

Just as its material character has evolved over the years, the English Hospital complex's function has shifted in response to the community's changing needs. After the completion of the new hospital in Salalem in 1935, the English Hospital focused on out-patient care and dispensary work. Between 1948 and 1982 when it closed, the hospital served as a relief and social work center. When yet another hospital opened in 1954, the complex became a rest home for the elderly. The Synod of the Arab Evangelical Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East took possession of the complex in 1956. Then, in 1964, the Holy Land Institute for the Deaf (HLID) opened on the site; it was the first school for children with disabilities. HLID became a "beacon" for Middle Eastern deaf education.

In 1996, HLID established the Salt Training and Resource Institute for Disability, Etc. (STRIDE).(1) All STRIDE activities were based at the HLID site in Salt, meaning that STRIDE lacked adequate facilities for its cross-disability training for rehabilitation workers and teachers. With permission from the Arab Evangelical Episcopal Church, HLID began the rehabilitation of the complex in 1998 for eventual re-use as STRIDE's training, resource, and respite care center. When complete, this building will provide STRIDE with a spacious location where it can carry out its goals in an environment designed expressly for people with disabilities.

The former hospital building will be the training center. One set of rooms has been designated for people with physical disabilities and another for those with visual impairment. A former doctor's residence adjacent to the hospital will become the administrative hub, and a number of flats above the old hospital will be converted into living quarters for trainees and others.(Figures 2-3) An integral part of the training center will be the service unit slated to be built on a vacant plot of land next to the hospital. This unit will include a kitchen and dining room, offices for outreach workers and administrative staff, a disabled living center, and sanitary facilities. The development will also include a number of small shops and an elevator that will render the multilevel complex accessible to all.

|

|

Figures 2 and 3. The former doctor’s residence, shown here before and after restoration, now serves as living quarters for STRIDE trainees. (Courtesy of the author.) |

Before the rehabilitation work, the buildings of the complex were in poor condition. All the stone façades were dirty, with many missing or inadequate fillings. The balconies had rotted, and the roof was leaking. Many of the stone arches over doors or windows had been damaged. All the inside walls had crumbling plaster or layers of oil-based paint. Most of the wooden doors and windows were broken, and the sanitary and electrical installations were damaged beyond repair.

The rehabilitation project began with work on the foundations and complex infrastructure in the fall of 1996. At the present time, the building houses the architect's and site office, and a small exhibition for visitors. Two flats near the site have also been renovated, and are now inhabited by short and longer-term volunteers working on the project. In 1999, work started on the three-floor, English Hospital building.

Thus far, HLID and STRIDE have received financial support for their multiphase project from the Embassies of Japan and the United Kingdom, British Overseas Aid, and other groups. The first and second phases, now complete, focused on the renovation of the offices and west terrace, the rehabilitation of the Old English Hospital for use as the training center, repairs to the retaining wall and structural reinforcement at different locations of the complex. Work is underway on tourist facilities and the renovation of various flats and shops.

STRIDE's new training center serves people with a range of disabilities, and the rehabilitated complex takes their requirements into consideration. Ramps have been installed in lieu of steps, door widths enlarged, and an elevator introduced. Door handles, switches, and taps, moreover, have been placed so that they are within reach of a person confined to a wheelchair; they are also suitable for use by people with hand impairments. Students in HLID's vocational training workshops made much of the metalwork and woodwork for the rehabilitation.

Following in the great tradition of social and medical services initiated in Salt almost 150 years ago, STRIDE has started the first cross-disability and community-based rehabilitation training programs in Jordan and the Middle East. The refurbishment of the Old English Hospital will demonstrate to the people of Salt that their distinctive town can be preserved and that the adaptive re-use of the English Hospital and other historic buildings can be compatible with the traditional building functions and the needs of modern society.

About the Author

Jawdat S. Goussous, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Architecture Department, Faculty of Engineering, Jordan University in Amman, Jordan.

Note

1. STRIDE's mandate is fourfold: 1) Train rehabilitation workers and teachers of disabled children, especially through cross-disability training courses (all disabilities in one program); 2) Develop educational and rehabilitative resources for use by and for people with disabilities, especially in the Arabic language; 3) Restore the Old Evangelical (English) Hospital in Salt and revive its community service role, by re-establishing it as a training center for STRIDE, whilst contributing to the restoration of Salt Town Center; and 4) Support and assist disabled individuals and their families through the provision of a respite care program.

Between 1995 and 2000, nearly 1,500 people attended STRIDE training and resource programs in Jordan, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, the West Bank, and other locations. STRIDE also produced many educational and rehabilitative resources in the last few years in both English and Arabic, such as the Deaf Kindergarten curriculum; a textbook for teachers of the deaf; vocational training curricula; guidelines for parents, teachers, and interpreters; and a dictionary of Yemeni sign language. The Sign Language Unit is also developing a dictionary of Jordanian Sign Language.