Research Report

Honoring James Hoban, Architect of the White House

by William B. Bushong

This year marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of James Hoban, the Irish-born architect best known on these shores for his design of the White House in Washington, DC. The commemoration—a collaborative effort among the White House Historical Association and the James Hoban Societies of Ireland and the United States—includes an exhibition, James Hoban: Architect of the White House, that opened at the White House Visitor Center on March 13, 2008, and a venue in Ireland; a special James Hoban issue of the journal, White House History; and a symposium cosponsored with the United States Capitol Historical Society, also in March, that examined Hoban as a federal architect, and local civic and church leader, plus Irish artisans in 19th-century Washington and residential architecture in the city from 1790 to 1830. The exhibition, publication, and symposium have brought new insights to a memorable Irish American success story.

Born in 1758 in a peasant cottage on the Desart Court estate of Lord Cuffe in County Kilkenny, Ireland, Hoban came to America with high ambitions. He designed and erected many buildings, but what keeps his name alive today is one special commission the executive mansion for the president of the United States, which most people know as the White House. Of the three architects who shaped the White House over the course of more than 200 years, Hoban was the most influential because he created the image of the house that has endured in the public consciousness to this day.(1)

The details of Hoban's life and personality remain a mystery. Most of his personal and business papers were lost in a fire in the 1880s. What is known of the man has come mostly from scattered drawings, public documents, and newspaper notices.(2) A prominent Washingtonian and well-known builder, Hoban served as the U.S. Government's principal architect until President Thomas Jefferson replaced him with Benjamin Henry Latrobe in 1803.(3)

Hoban arrived in Philadelphia from Ireland around 1785. His time there was brief: Around 1787, he relocated to Charleston, South Carolina, where he set up a partnership with fellow Irishman Pierce Purcell, a master carpenter, and opened a drawing school.(4) His influential references for work in Charleston attracted the attention of President George Washington, who invited Hoban to Washington, DC, to design a new executive mansion for the President of the United States.

Hoban arrived in Washington in 1792. He was instrumental in organizing Federal Lodge No. One of Freemasons in September 1793. One week later, President Washington laid the cornerstone for the Capitol, a ceremony in which the Masons participated.(5) His marriage to Susana Sewell, a member of a prominent Maryland family, meant that the architect was in Washington to stay. The Hobans moved into a two-story brick house on the north side of F Street, between 14th and 16th, not far from the White House site.(6)

Besides the Masonic lodge, Hoban helped establish Saint Patrick's Catholic Church in 1794, convincing Father Anthony Caffrey to come to the United States from Ireland to head it up. He also formed the District's first militia company in 1796, which had a profound influence on the maintenance of law and order in the young capital. Sensitive to the needs of Washington residents, he served on the city council for 20 years.(7)

Proud of his Irish heritage, Hoban gave a voice in local politics to the great number of Irish immigrants in Washington who worked as skilled and unskilled laborers, draymen, tavern keepers, blacksmiths, grocers, and boarding house proprietors. He founded the Sons of Erin in 1802 to promote naturalization and help Irish-born workers with housing, food, and medical services.(8)

James and Susana Sewell Hoban had 10 children. The best known of them was James Hoban Jr., a powerful orator and respected Washington lawyer who completed his career as the District Attorney for the District of Columbia. Family tradition held that an 1844 daguerreotype showed that James Jr., was the "spitting image" of his father. Like his father, James Jr., was very proud of his Irish heritage, wrote and lectured on Irish eloquence and wit, and promoted Ireland's independence from Great Britain.(9)

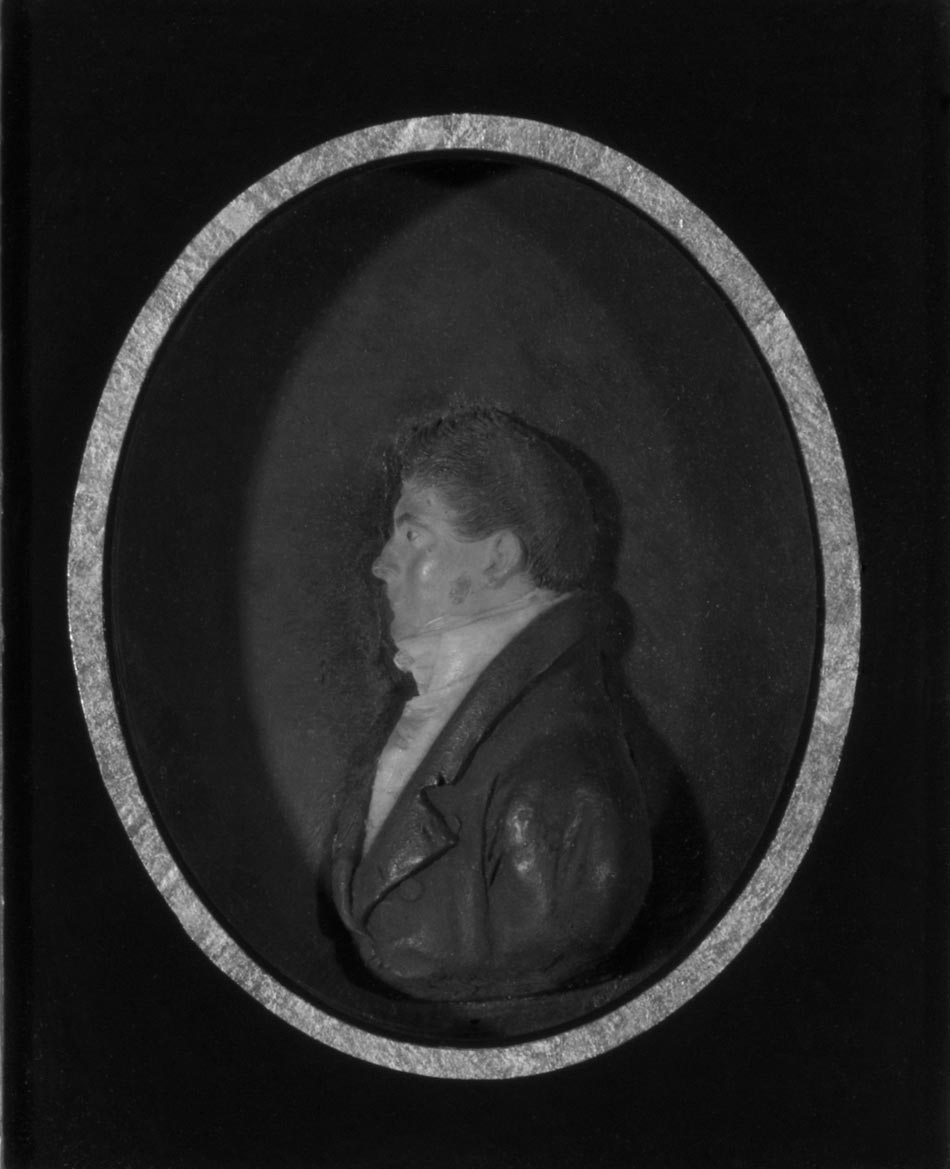

What the elder James Hoban looked like is entirely transmitted in a wax image passed down through his family. He probably sat for the bas-relief portrait as a wedding gift to Susana in 1799. Curators attribute the color miniature to German-born John Christian Rauschner.(Figure 1) It shows a youthful profile, thick brown hair, rosy complexion, and broad shoulders and chest that suggest a hardy physique, just as one might expect of a builder accustomed to working with his hands.(10)

In 1932, the American illustrator N.C. Wyeth created a poster for the Pennsylvania Railroad promoting travel to the District of Columbia for the bicentennial of the birth of George Washington. Wyeth based the poster on Washington's personal interest in the design and construction of the White House, depicting a presidential visit to the site in the company of architect Hoban.(Figure 2) To the left are visitors or perhaps friends of the president and to the right are Hoban's assistants.(11)

The most prolific year of Hoban portraiture came with a 1981 commemorative Hoban stamp jointly designed and issued by the United States and Ireland. Irish artist Ron Mercer created the portrait of Hoban from his portrait and Walter D. Richards, an American stamp designer renowned for his work on the American Architecture Series.(12) With the stamp's issuance numerous commemorative covers produced new portraits of Hoban.

Hoban died in 1831, having completed the north portico—the enduring image of the White House. He left a large estate of more than $60,000 (approximately $1.4 million in 2006 dollars), with property in the city and farms in Maryland. His children shared most of the estate. The slaves were to be sold.(13) He was buried beside Susana in the old graveyard at St. Patrick's Church. The graves were moved in 1863 to the new Mount Olivet Cemetery on Bladensburg Road near Washington, where they remain.(14)

Despite the efforts of the last several decades to create a profile of James Hoban, he remains a mystery. His thoughts and ideas, beyond what can be inferred from letters to government officials and activities reported in contemporary newspapers, remain missing pieces of a puzzle. Portraits and fragmentary records are informative but require the imagination to understand the man's character.

About the Author

William B. Bushong is a historian at the White House Historical Association.

Notes

1. William Seale, The White House: The History of an American Idea (Washington, DC: White House Historical Association, 2001), 2-35, 159-201, 237-77. Hoban was the first of three architects to leave his mark on the White House. The second was Charles F. McKim of the firm, McKim, Mead & White, who directed the 1902 Beaux Arts White House restoration for Theodore Roosevelt. The third was Lorenzo S. Winslow, who gutted and rebuilt the house's neoclassical interior for President Harry S. Truman between 1948 and 1952.

2. Martin I.J. Griffin, "James Hoban, the Architect and Builder of the White House," American Catholic Historical Researches 3 no. 1 (1907): 35-52; and Pamela Scott and Antoinette J. Lee, Buildings of the District of Columbia (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1993), 20.

3. President Thomas Jefferson replaced Hoban with the architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe.

4. One of Hoban's students in Charleston was Robert Mills, who would have an illustrious career as an American architect.

5. Gary Scott, "James Hoban, First Worshipful Master of Federal Lodge No. 1," speech presented September 13, 1998, Mount Olivet Cemetery, Washington, DC.

6. Griffin, 2.

7. William W. Warner, At Peace With All Their Neighbors: Catholics and Catholicism in the National Capital, 1787-1860 (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 1994), 153, 161-62.

8. Morris J. McGregor, A Parish for the Federal City: St. Patrick's in Washington, 1794-1994 (Washington, DC: Catholic University Press, 1994), 42-44.

9. John E. Norris, Eulogy on the Life and Character of James Hoban, Esq. (Washington, DC: W. Blanchard Printer, 1846).

10. William Kloss and Doreen Bolger, Art in the White House: A Nation's Pride (Washington, DC: White House Historical Association in cooperation with the National Geographic Society; New York: Distributed by H.N. Abrams, 1992), 339.

11. Christine B. Podmaniczky and Charles H. Wolfinger, "N.C. Wyeth's Pennsylvania Railroad Paintings, The Keystone (Spring 2001), 55-58.

12. James H. Bruns, "Stamps and Coins," Washington Post, October 25, 1981, G6.

13. Wesley E. Pippenger, comp., District of Columbia Probate Records, Will Books 1 through 6, 1801-1852 and Estate Files, 1801-1852, Arlington, VA, 2003: 169. Using the Consumer Price Index, Hoban's worth calculated by the Consumer Price Index, see Samuel H. Williamson, "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1790 - 2006," MeasuringWorth.Com, 2007.

14. Griffin, "James Hoban, The Architect and Builder of the White House," 47.