Exhibit Review

Slavery in New York

New-York Historical Society, New York, NY Curator: Richard Rabinowitz

Permanent

The unearthing of the 18th-century African Burial Ground, the final resting place of enslaved and free Africans in New York City, during the course of a federal construction project in Lower Manhattan in 1991 caught New Yorkers by surprise.(1) "Wasn't slavery a Southern institution? Wasn't New York a safe haven for runaway slaves?" Fourteen years later, Slavery in New York, one of the New-York Historical Society's newest and largest permanent exhibits, focuses on that discovery and attempts to correct many of the myths about New York's role in the history of slavery.

Slavery in New York sets slavery within the context of a colonial and early federal port city that played a central role in the Atlantic triangle trade, the imperial wars over sugar and slaves, and the American Revolution. Those contributed to its meteoric growth first under Dutch, and then British, colonial rule, and ultimately within a new nation. Organized chronologically from the 1620s to 1827, the year slavery was abolished in New York State, the exhibit is the first of a two-part permanent installation. The second, Commerce and Conscience: New York, Slavery, and the Civil War, which is scheduled to open November 17, 2006, will continue the story through the second half of the 19th century. The exhibit includes a companion publication, Slavery in New York, edited by Ira Berlin and Leslie M. Harris, and a website.(2)

Artifacts on display from the African Burial Ground are especially moving. They include the bones of enslaved Africans that tell the stories of childhood malnutrition and hard labor, along with a silver sugar dish, tea caddy, and other luxury items made by enslaved Africans. The exhibit also features documentary evidence, such as newspaper ads for runaways, where "previously anonymous blacks suddenly [became] people with names, looks [and] skills." Court records bring the voices of blacks in civic life to light through the horrific testimony of four enslaved Africans that visitors can hear at a listening station.

|

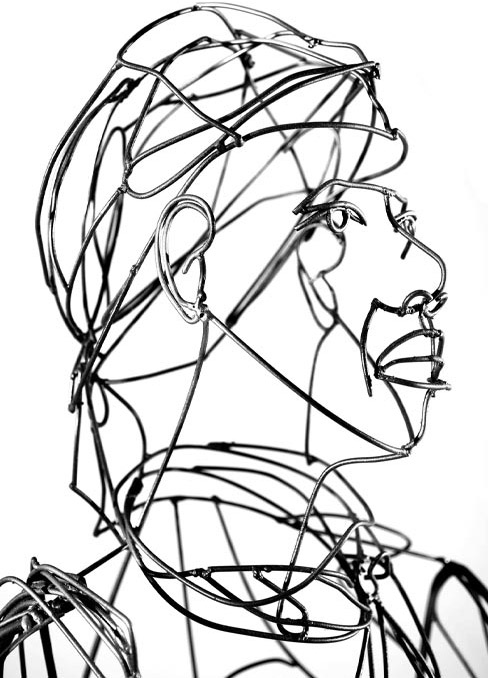

This sculpture representing one of the first Africans in New Amsterdam was commissioned from the sculptor Deryck Fraser for the exhibition. (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.) |

Slavery in New York effectively uses technology to tell its story. An interactive display invites visitors to "stand next to the captain as he does the business of slave trading." An ordinary ledger book reveals an itemized list of goods bought and sold en route between West Africa and New York, including a child that could be bought for about 80 gallons of rum made with New World sugar harvested by enslaved Africans. The prices of Africans, too, are displayed over a 100-year period (from 1675-1775), with their initial cost in West Africa (in contemporary pounds sterling), the markup in New York (as little as about 100 percent, as much as 1,000 percent), and, for the purposes of comparison, the total cost in today's dollars. A widescreen monitor displaying slave trade-related financial information in a stock ticker across the bottom of a mock cable news show helps drive home the fact that 12 million human beings were traded as commodities over the course of 400 years.

Equally forceful are the thick wire sculptures that portray enslaved Africans laboring and the story maps showing the growth of Manhattan. The juxtaposition of a familiar historical timeline of the "War for American Independence" and a timeline of the "Struggle for Black Freedom" highlights the difficult choice put before African Americans during the Revolutionary War: fight for the slave owners or fight for Britain and a chance at freedom. As a story about urban slavery in the North, Slavery in New York addresses both the human costs of slavery and the contributions the enslaved made in building New Amsterdam (New York City), including what became known as Wall Street, before Southern cotton was king.

|

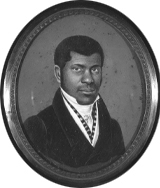

Caesar, shown here in this daguerreotype, outlived three slave masters on the Nicoll estate in Bethlehem, New York, outside Albany, until his death at the age of 115. (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.)

|

|

The painter Anthony Meucci painted this portrait of Pierre Toussaint, a prosperous Haitian immigrant who served as the hairdresser to elegant New Yorkers and an important bulwark of his fellow immigrants in the same period. (Courtesy of the New-York Historical Society.) |

At times, Slavery in New York treats historical evidence perfunctorily. The visitor reads, for instance, that slavery "always co-existed" with other forms of "unfree" labor, such as indentured servitude, and that it became tied to skin color beginning in the late 17th century; however, neither of these important and potentially confusing statements are treated in depth. Most surprising is the lack of information on other slave-holding colonies and countries. While the exhibit notes that 42 percent of New York households owned slaves in 1703—only Charleston, South Carolina, had more at the time—no explanation is given as to why that was the case. The State of New York begrudgingly abolished slavery in 1827, but its economy, like that of England and Holland, remained as closely tied to the institution of slavery as New England's textile mills were to slave-grown cotton. The exhibit missed an opportunity to highlight these contradictions.

Nevertheless, the exhibit succeeds as an introduction to the study of slavery as a global institution. Building upon the irrefutable physical evidence of slavery in New York that was unearthed in 1991, Slavery in New York advances the dialogue on a significant yet painful chapter in the city's past that will resonate with a broad audience.

Holly Werner Thomas

Washington, DC

Notes

1. In February 2006, President George W. Bush proclaimed the African Burial Ground a national monument to be administered by the National Park Service.

2. Ira Berlin and Leslie Harris, eds., Slavery in New York: The African American Experience (New York, NY: The New-York Historical Society and the New Press, 2005). The exhibit website is http://www.slaveryinnewyork.org.