Interview

An Interview with Elizabeth Barlow Rogers

by Antoinette J. Lee

|

Courtesy of Elizabeth Barlow Rogers |

Elizabeth Barlow Rogers is a pioneer in the preservation and restoration of urban parks. Born in San Antonio, Rogers was educated at Wellesley College and obtained a master's degree in city planning from Yale University. In 1971, she published her first book, The Forests and Wetlands of New York, followed a year later by Frederick Law Olmsted's New York. In 1975, she became director of the Central Park Task Force, which led to her appointment as Central Park Administrator in 1979. She held this position as well as that of President of the Central Park Conservancy starting in 1980, until 1996. During this period, she directed the landscape preservation planning process and authored Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan, which details the analyses, surveys, and recommendations that continue to serve as a systematic program for managing Central Park today. She is author of the 2001 book, Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History. Antoinette J. Lee (AJL), former CRM Journal editor, interviewed Rogers in her New York City home on November 16, 2005.

AJL: Please tell us about where you were born, where you grew up, and how you came to develop an interest in historic preservation and landscapes.

EBR: I grew up on the edge of San Antonio, where I played in a vacant lot that seemed to a small child to be deep and mysterious woods. A nearby park provided me with the ability to explore further afield. Back then children were safe and could wander about the neighborhood at will. This was the beginning of my interest in nature. Historic preservation came later.

I graduated from Wellesley College, which has a beautiful campus. I found the New England landscape to be very different from the Texas landscape, and it had an unconscious influence on me. At Wellesley, I majored in art history. In my mind, landscape architecture is an extension of architecture, painting, and sculpture, the topics traditionally covered in art history courses.

AJL: Were there major planning or design figures at Wellesley who influenced your education and career?

EBR: In the 1950s, the professors at Wellesley were outstanding. I would be hard pressed to single out anyone in particular. Some were highly trained German-educated émigrés.

AJL: What is the Wellesley campus like?

EBR: When Caroline Hazard was president of Wellesley College (1899-1910), she invited Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., to advise on the campus plan. He was impressed by the site's glacier-created topography, which includes beautiful Lake Waban. In the 1920s, buildings designed by Ralph Adams Cram and others were constructed on hilltops, leaving open meadows in the valleys between them as Olmsted had advised.

Ten years ago, I was asked to lead a visiting committee that Wellesley's current president, Diana Walsh, assembled to study the campus's deteriorated landscape. The committee's report recommended a comprehensive management and restoration plan that would treat the campus in its entirety and systemically. The landscape architect Michael Van Valkenburgh directed the planning process. His firm then prepared a design for Alumnae Valley that replaced an ugly parking lot with wetland meadows containing small ponds. This landscape design was incorporated into the college's recent capital campaign and has recently been completed.

AJL: What did you do after graduating from Wellesley?

EBR: After Wellesley, I moved to Washington, DC, where my first husband was an officer in the Navy. At that time—the end of the Eisenhower era—the nation's capital was a sleepy Southern city. There I discovered Rock Creek Park, Georgetown, and the beauty of L'Enfant's monumental plan, which had been extended, clarified, and embellished with the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials at the turn of the 20th century.

AJL: What did you do next?

EBR: I enrolled in the city planning program at Yale University, where I learned how to look at cities as design problems. Jane Jacobs's famous book, The Life and Death of Great American Cities, published in 1961, was for me very influential. But my professors did not uniformly endorse my advocacy of a denser kind of planning, cluster development, and open space preservation because this was the era of urban renewal. I was very interested in regional planning as typified by Reston, Virginia, and Columbia, Maryland, both of which were then just getting started. I followed what was going on in one of the older neighborhoods in New Haven, Wooster Square, where houses were being restored with appropriate materials. At Yale I was fortunate to study city planning with Christopher Tunnard, who is remembered today as an early champion of the modernist style in garden design.

AJL: What were some of your early planning projects?

EBR: After I received my master's degree in city planning in 1964, I moved to New York City. Because of my interest in open space planning, which included protecting parks and nature, I became a volunteer with the Parks Council. I studied the city's waterfronts. Those that ringed the edge of Manhattan were still mostly industrial port facilities. In the other boroughs, I discovered some of the outlying parks of the city, such as the wildlife refuge in Jamaica Bay and forested Inwood Hill Park in northern Manhattan. I made excursions to these places, which I followed up with historical research at the New-York Historical Society and other libraries. The result of this was my first book, The Forests and Wetlands of New York City.(1)

New York parks, of course, are not primarily nature preserves. Most are designed landscapes. I wondered about how Central Park, Prospect Park, and other great 19th-century New York City parks had come into being. This was during a time when Frederick Law Olmsted was virtually forgotten. I did research on Olmsted, which led to my second book, Frederick Law Olmsted's New York,(2) published in conjunction with the Olmsted Sesquicentennial exhibition at the Whitney Museum. My research on Olmsted led me to the late Charles McLaughlin of Washington, DC, who sent me the original typescript of his Harvard thesis, "The Selected Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted," the precursor of the publication of the multi-volume Frederick Law Olmsted papers, an editorial project that has done a remarkable job of re-establishing Olmsted's reputation.

AJL: Describe the evolution of Central Park from its status in the 1970s through its revival and preservation during the past quarter century.

EBR: The New York City Landmarks Commission was established in 1965, and in 1974, Central Park was designated as the city's first landscape landmark.

The mid-1970s, however, represented a low point in the city's fiscal fortunes and, in spite of its historic landmark status, Central Park was poorly maintained and considered unsafe. Garbage lay on the ground; benches were broken; light fixtures did not work. Graffiti was found on just about every stone, brick, and wood surface. The lawns were bare and without grass. The New York City Parks Department was in a state of paralysis, and the workforce was demoralized.

During the 1970s, the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA), within the U.S. Department of Labor, provided grants for job training. The Parks Department used the CETA program to keep some of its existing workforce employed. This was, of course, contrary to the intent of the law, which was designed to teach new skills to unemployed youths. A friend who was then serving as a deputy parks commissioner asked me to run a summer program for teenagers when additional federal funding produced money for this purpose. I accepted the job and became an employee of the Central Park Task Force, a small privately-funded not-for-profit organization operating within the Parks Department. After the summer, I became the director of the Task Force. It encouraged volunteers to perform badly needed horticultural maintenance and school teachers to use the park as a learning laboratory. A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities enabled us to produce a film for public television. Exxon funded The Central Park Book, a series of essays on the park's history and natural history. The Astor Foundation enabled us to undertake an educational program, and a wonderful donor, Iphigene Sulzberger, allowed us to continue the summer youth program the following year.

The Central Park Community Fund, which had been founded in 1974 to provide funds for needed maintenance equipment, sponsored a management study that analyzed the management structure of the park and suggested ways to improve it. I initiated an internship program that hired young graduates in horticultural degree-granting programs. This allowed us to begin assembling an auxiliary workforce made up of privately-supported employees.

With the election of Mayor Edward I. Koch in 1978, his first parks commissioner, Gordon J. Davis, began to restructure the agency. In 1979, he asked the mayor to appoint me as the privately-funded Central Park administrator. In addition, funds to continue the work begun by the Central Park Task Force had to come from private sources because the city was still digging its way out of its fiscal crisis. This led to the creation of the Central Park Conservancy in 1980. With the establishment of the Central Park Conservancy, the Task Force and the Community Fund went out of business. Some board members from each organization became the nucleus from which the Conservancy's board grew.

As Central Park administrator and head of the Conservancy, I was able to convince additional prospective board members and donors that Central Park was like any other major cultural institution. It was as rich as a library or museum in its collections—specimen trees, statuary, wildlife—and a great cultural and educational resource. It was deserving of a board and private support. Happily, we were successful in building a multi-ethnic citizen-led board with broad contacts in the corporate and philanthropic sectors of the city.

AJL: Tell us more about the restoration plan for Central Park.

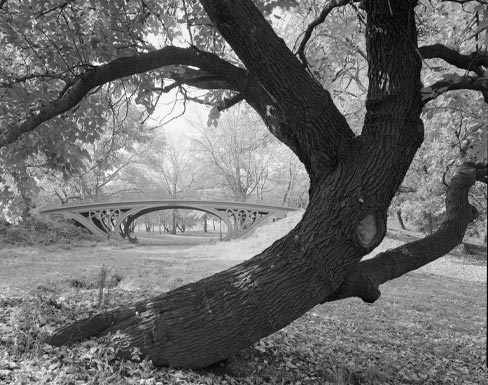

EBR: At the outset, the mission of the Conservancy was to make Central Park clean, safe, and beautiful. People were especially concerned about park safety in those days. Along with rebuilding the workforce, we needed to revisit the park's original design and to study the existing park, not piecemeal but in its entirety. I assembled a team of professionals led by four landscape architects who directed the work of architects, urban sociologists, soil scientists, hydrologists, and wildlife experts as we studied the park's 843 acres between 1982 and 1985. The plan, published as Rebuilding Central Park: A Management and Restoration Plan,(3) has served as the basis for the park's restoration up to the present. It has also been the basis for fundraising. We guided gifts for individual projects in such a way that they became part of a greater whole. Today, this kind of plan would be done with GIS technology, which would give it a more dynamic representation; however, the basic methodologies we used to inventory the park and plan its restoration are still valid.(Figure 1)

Central Park's restoration is based on understanding that Central Park is a single, unified composition, an organic whole. It contains interconnected systems of drainage, traffic circulation, architecture, and vegetation. In order for a restoration to be effective, it has to be regarded as a series of integrated components rather than as a number of stand-alone projects.(Figure 2)

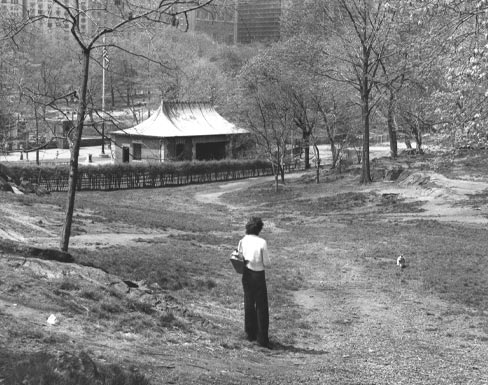

Our management and restoration plan offered a clearly defined shopping list of gift opportunities, including requests for funds for an endowment. It would have been pointless to restore the physical park without creating the tree crew, turf crew, planting crew, historic restoration construction crew, and zone gardeners to maintain it.(Figures 3 and 4)

|

Figure 3. This image of Bethesda Fountain in Central Park was made in 1975. (Courtesy of Patricia Heintzelman.) |

|

Figure 4. This 1975 image illustrates the area behind Wollman Rink in Central Park. (Courtesy of Patricia Heintzelman.) |

Today, the Conservancy provides more than 85 percent of Central Park's $23 million annual operating budget and is responsible for all the basic care of the park. It does so under contract with the City of New York Department of Parks and Recreation. Ownership and park policy remains with the city, while the Conservancy has responsibility for day-to-day management. Today, the Conservancy's staff cares for Central Park and handles much of the work, from conserving monuments, bridges, and buildings to pruning trees, raking leaves, planting shrubs and flowers, and removing graffiti. Volunteers add a critical component to the workforce, giving the park the most precious gift anyone can give: his or her time.(Figure 5)

|

Figure 5. The 2005 outdoors installation, "The Gates," included the Gapstow Bridge in Central Park. The exhibit drew thousands of visitors to the park. (Courtesy of Victorio Loubriel.) |

AJL: What was the effect of Central Park's turn-around on parks in other urban areas?

EBR: Other cities are interested in the Central Park public/private partnership model and want to learn more about how it operates. However, many public officials are reluctant to turn over major responsibility for managing parks to private organizations. Launching a park conservancy requires an act of political will, and this depends on both citizen initiative and a positive attitude on the part of the city government.

AJL: What have you done since leaving the Conservancy and your position of Central Park administrator in 1995?

EBR: I left when the partnership to maintain Central Park became institutionalized and had a life of its own. I was there a total of 20 years.

After leaving, I had the time to complete my most recent book, Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History.(4) This book required a good deal of travel and research time. It looks at the landscapes of cities, parks, and gardens as products of human culture from prehistoric time to the present.

In 2002, I started a program in Garden History and Landscape Studies at the Bard Graduate Center, and this gave me an opportunity to teach a survey course based on the contents of my book. I am now working on a broader basis to build my field through the Foundation for Landscape Studies. One of our initiatives is publication of the journal Site/Lines.

AJL: When people ask you how they can have a career like yours, what do you advise them?

EBR: There is no recipe for this career. Mine grew out of a moment in New York City's history and a certain passion on my part.

The Central Park Conservancy was born in a time of adversity. Private citizens were willing to roll up their sleeves and get the park back on its feet. Many of the people who began their careers in Central Park have gone on to remarkable jobs in historic landscape preservation elsewhere. And many of the people I hired have remained employees of the Conservancy and had equally remarkable careers. Douglas Blonsky, my current successor as Central Park administrator and president of the Central Park Conservancy, whom I hired 21 years ago, is in my opinion the best leader of park stewardship in America.

Today, partnerships between the public and private sectors and government agencies have become common. These kinds of partnerships present new challenges and rewards as well as the makings of new kinds of careers. It is a matter of taking the initiative when these opportunities occur.

Notes

1. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, The Forests and Wetlands of New York (Boston, MA: Little Brown, 1971).

2. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Frederick Law Olmsted's New York (New York, NY: Whitney Museum Praeger, 1972).

3. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Rebuilding Central Park A Management and Restoration Plan (New York, NY: Central Park Conservancy, 1985).

4. Elizabeth Barlow Rogers, Landscape Design: A Cultural and Architectural History (New York, NY: Abrams, 2001).