Last updated: January 16, 2026

Article

Scientist Spotlight: Pollinator Researchers Helping Parks

Meet the buzz-worthy scientists helping national parks collect crucial pollinator data!

October 2025

Pollinators in National Parks

What comes to mind when you think of national parks? The humbling grandeur of the Grand Canyon, the majestic geology of Yellowstone, or perhaps the vast beauty of the Grand Tetons? While these iconic features of the National Park system draw millions of visitors per year, some of the biggest treasures in the parks are tiny. Sometimes the smallest creatures can have huge impacts. Pollinators are animals that move pollen from flower to flower, facilitating plant reproduction. This critical ecosystem service supports plant genetic diversity, flourishing ecosystems, soil stability, and healthy food webs. Wind and water can pollinate plants too!

Left image

Credit: NPS

Right image

Credit: NPS / Christina Martin

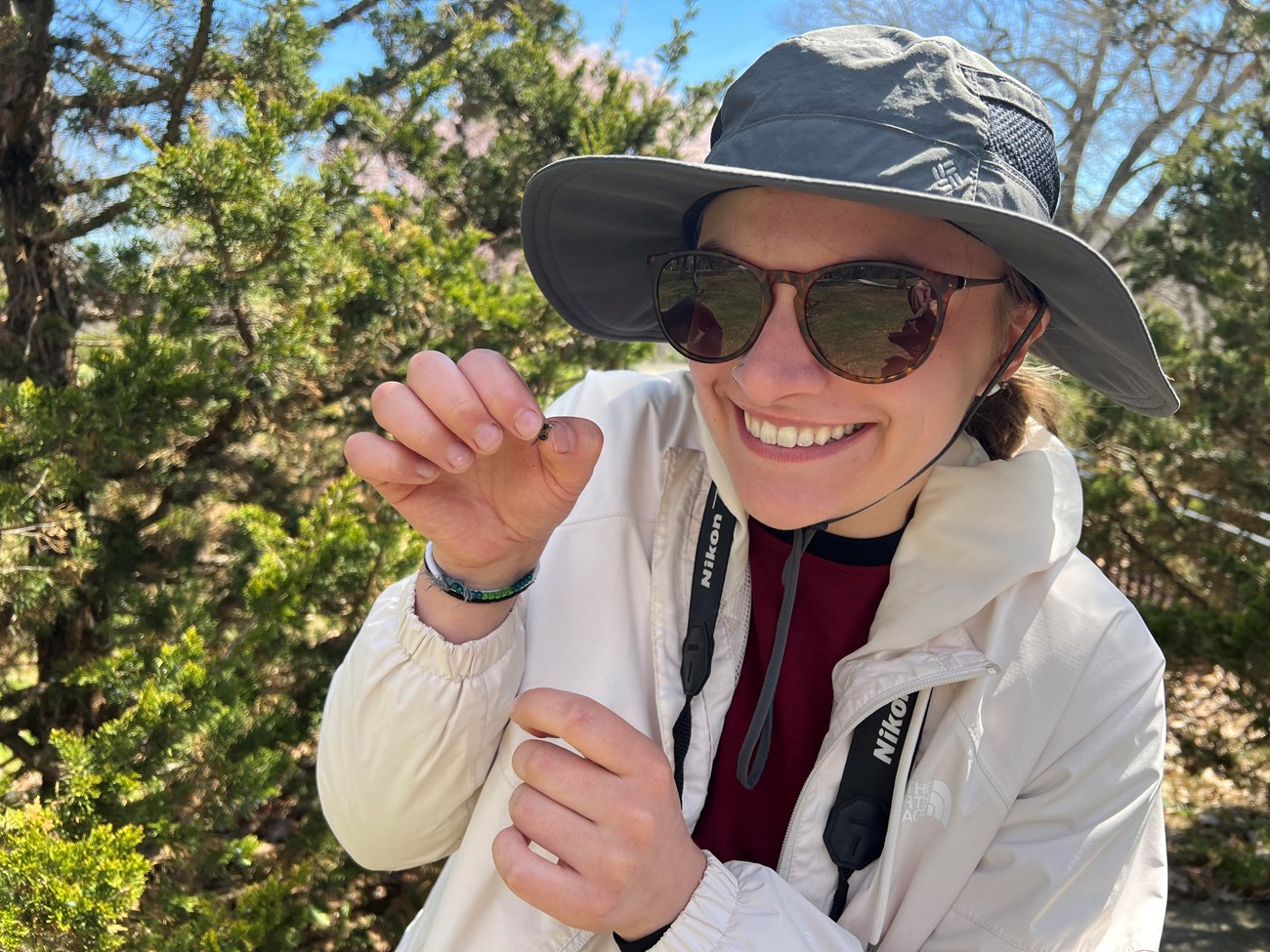

The enormity of the Grand Canyon evokes a sense of wonder to visitors. While they may be miniscule in comparison, pollinators are both beautiful and critical to maintaining ecosystems. They come in a variety of shapes, sizes, and colors, such as this lovely green sweat bee (Agapostemon sp.).

Who does it best?

There are many animals that act as pollinators, including birds, bats, flies, bees, butterflies, moths, beetles, reptiles, and even rodents. However, bees are arguably the most efficient pollinators due to their unique diet, which ties them intricately to flowers. Flowers produce nectar—a sweet sugary liquid that provides animals with the energy they need. They also produce pollen, a powdery substance produced by male flowers, which is essential for reproduction and also makes you sneeze! Most pollinators are attracted to the energy-rich nectar, unintentionally transferring pollen that gets stuck to their fur, feathers, or skin to female flowers.

- Duration:

- 11.128 seconds

A bumble bee buzz pollinating yellow foxglove at Minute Man National Historical Park.

NPS / Christina Martin

Bees are attracted to the pollen as well as nectar, which serves as an important source of protein, carbohydrates, fats, and micronutrients. Bees collect pollen and nectar to bring back to their nests to feed their offspring. Because bees intentionally collect, manipulate, and pack pollen onto their bodies to bring back to their nests, they tend to spend more time at flowers and move more pollen between blooms. Bees can become coated in pollen, which inadvertently gets moved to other flowers as they forage, making them among the most efficient pollinators! However, bees cannot pollinate every flowering plant species, and diverse pollinator populations are critical to maintaining stable ecosystems.

NPS / Christina Martin

A red-bellied miner bee (Andrena erythrogaster), carrying pollen on its fuzzy hindlegs, a bumble bee (Bombus sp.) with a pollen ball stuck to the flattened part of the hindleg (called the corbicula or pollen basket) for transport, and a Georgia mason bee (Osmia georgica) carrying pollen on the underside of its abdomen. These bees illustrate how species vary in their pollen transportation methods.

NPS / Christina Martin

Native versus non-native bees

There are over 3,700 species of native bees in North America. Native pollinator species tend to support ecosystems more effectively than non-native ones because they have evolved alongside local vegetation, forming complex relationships that non-native species often lack or disrupt. The European honey bee (Apis mellifera) plays an important role in agriculture but is not native to North America. Honey bees can spread diseases to native bees and compete with them for resources, putting native bee species at risk.

The value of species inventory data in national parks

The National Park Service (NPS) Inventory and Monitoring (I&M) Program helps park managers get information about the species that live in their park. The I&M Program collaborates with universities, non-profit organizations, tribes, consulting companies, and government agencies to collect these crucial data. The inventories are tied to specific land management plans and practices, such as prescribed burning or mowing, and are designed to determine the impact of management practices on the species being surveyed. Inventory data helps the parks make sound management decisions based on the best science available, such as the best time of year to mow or apply herbicide on invasive plants that minimizes harm to pollinators.

NPS / A. Hernandez

Research partners collect a variety of data in the parks, including:

- Species occurrence (presence/absence)

- Species counts (abundance)

- Species diversity (number of species)

- Species phenology (seasonal timing of activity)

- Which floral species pollinators are feeding from

- Locations of floral resources

NPS / Sarah Whipple

By combining the data collected during the inventory surveys with the history of land management activities at the park, researchers can assess the impact of management activities on pollinator populations. This information ensures that park managers can support pollinators and their habitat for years to come, preserving these gems for future generations.

NPS / Christina Martin (left), NPS / Michelle Boone (right)

Meet the Scientists!

Seven scientists who are helping collect pollinator data on national park lands in collaboration with the NPS I&M Program were interviewed to learn more about their work. These researchers span a range of geographic locations, areas of expertise, and career stages. Each interviewee responded to the eight questions below:

- What is your job title and where do you work?

- How did you get started in pollinator research?

- What taxa do you study and what is your favorite fact about them?

- Why did you choose to study pollinators?

- What is your favorite thing about your job?

- What is something about your work that people might find surprising?

- What keeps you motivated to continue your research, even when it's difficult?

- What is one thing you want the public to know about pollinators?

Keep reading to learn more about their exciting work!

© Jennifer Thieme

Logan Rowe

Conservation Associate, Michigan Natural Features Inventory

NPS projects: Bee and butterfly inventories at Isle Royale National Park, Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, and Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore

© Logan Rowe

Logan Rowe, M.S., works for the Michigan Natural Features Inventory, a natural heritage program through Michigan State University that conducts species inventories and research to inform conservation in the state. For Logan, a fascination with pollinators began over a decade ago with a seasonal job surveying endangered Karner blue and at-risk frosted elfin butterflies. That experience ignited a curiosity that carried through his undergraduate research on monarch butterfly migration and ultimately led to studying bees during his master’s program at MSU. Now, his work extends beyond bees to another often-overlooked group of pollinators: moths.

Logan’s favorite? The borer moths of the genus Papaipema. These moths have incredibly specialized relationships with native plants, such as blazing star and Culver’s root, making them excellent indicators of habitat health. Their reliance on rare plant species means that protecting the moths also protects the ecosystems they call home. “I love moths,” Logan says. “There’s so much to discover, and their interactions with plants are fascinating.”

© Logan Rowe

The draw of pollinators, for Logan, is twofold. They are crucial for healthy ecosystems and endlessly diverse. “There are so many different rabbit holes to go down,” he says. “Pollinators are vital for stabilizing native plant communities—most flowering plants out in the wild depend on them. And each species has a unique role.” This diversity keeps his work fresh, offering countless new questions to explore.

© Logan Rowe

One of the greatest challenges of his job is the physical toll of conducting field work. Logan’s field season stretches from April to October, often requiring travel across Michigan and long days navigating dense vegetation. “People see the amazing photos from the field, but there’s a lot of bushwhacking involved to get there,” he says with a laugh. “It’s a grueling season.”

But even when the work is difficult, Logan remains motivated. He studies species that, in some cases, would be extinct without conservation efforts. The Poweshiek skipperling, for example, once thrived across the Midwest but now survives in only three sites in Michigan within the U.S portion of its historic range. Knowing that a species relies on scientists for survival keeps him going. There’s always more to learn, and he feels a responsibility to advocate for these species.

Pollinators are like an engine. Every part matters, even if you don’t always see its role. If you remove one piece, you don’t know what the consequences will be. That’s why we need to protect them all.

Photos courtesy of Logan Rowe

Christina Martin

Research Scientist and Communication Specialist, NPS I&M Program

NPS projects: Bee and butterfly inventories at Minute Man National Historical Park, bee inventory at Boston Harbor Islands, and monarch butterfly inventory at Dinosaur National Monument

NPS / Christina Martin

Christina Martin, M.S., works with the NPS I&M Program, where she collects data to support pollinator inventories and produces science communication pieces to inform the public about inventory projects in parks. For Christina, a passion for pollinators began in college with her school’s beekeeping club. Learning to care for honey bees introduced her to the challenges they face, from disease to pesticide exposure. This curiosity eventually shaped her graduate research on honey bees. Along the way, she realized that while honey bees are vital for agriculture, native pollinators are the true backbone of ecosystems. This realization steered her toward a career dedicated to studying and conserving native pollinators.

NPS / Christina Martin

Since then, her work has taken her to national parks across the country. From the high deserts of Utah to the forests of New England, she has helped inventory bees and butterflies to provide information to park managers to make science-based management decisions that support pollinators. Through her research experiences, she has come to understand that supporting pollinators requires a holistic approach—considering the plants they rely on and the broader ecological factors that shape their survival.

NPS / Christina Martin

One of the most rewarding aspects of her job is the thrill of discovery, whether it’s observing a behavior she’s never seen before or finding an unexpected species. Just as fulfilling is sharing those discoveries with others. Christina enjoys using photography to reveal the hidden beauty of pollinators. “It’s incredible how much life is happening at this small scale which we often overlook,” she says. “I love helping others experience a sense of wonder for the tiny creatures around us.”

Even in the face of challenges, Christina remains hopeful. New technologies, like tiny Bluetooth trackers for monarch butterflies and bumble bees, are expanding what scientists can learn. And as more people—scientists, land managers, and the public—join conservation efforts, she believes real progress is possible.

NPS / Christina Martin

Check out Christina's article about her research on native bees at Minute Man National Historical Park and her web articles highlighting I&M inventory projects (scroll to bottom of webpage for articles)!

Native plants are essential for pollinators and healthy ecosystems! They provide the food and shelter that native bees, butterflies, and other wildlife depend on. Planting a diverse mix of locally native plants helps support a thriving pollinator community. With so many non-native and invasive species available, choosing the right plants can feel overwhelming, but a quick online search or local plant guide can help you get started.

NPS

Megan Blanchard

Research Associate, University of Colorado Museum of Natural History

NPS projects: Bee and butterfly inventories at Colorado National Monument and Dinosaur National Monument

Photo courtesy of Adrian Carper

Megan Blanchard, Ph.D., is a research associate at the University of Colorado Boulder Museum of Natural History who studies plant-pollinator networks and ecology. For Megan, the path to pollinator research was unexpected. Her background in plant-insect interactions initially focused on caterpillars and plant chemical defenses, but she hadn’t considered pollination—until a project changed her perspective. Hired to contribute to the Colorado Native Pollinating Insect Health Study, Megan took a deep dive into pollinator research across the state and beyond. The more she learned, the more she wanted to know.

Photo courtesy of Adrian Carper

Now, Megan’s work focuses on bees, though she still carries an ecologist’s broad view of insect-plant systems. Her favorite part of the job? The fieldwork. "I've done a lot of cool fieldwork in my career, but collecting bees might be the most fun," she says. Surveying bees in national monuments, surrounded by dramatic landscapes, is one of the best parts of the job. Identifying the plants those bees depend on makes the experience even richer.

When asked to share a fact about pollinators that often surprises people, Megan noted how people typically do not realize just how diverse bees truly are. "We're up to 1,009 species in Colorado as of 2025, and we’ll likely add more as we continue identifying specimens from this project," she says, referencing her work at Dinosaur and Colorado National Monuments. Their variety in size, shape, and color still amazes her, even as an insect expert. Another lesser-known fact? Some herbivorous caterpillars, such as corn earworms, can be cannibalistic in certain circumstances. "It's rare, but it happens," she adds. Pollinators are endlessly fascinating creatures.

© Megan Blanchard

Corn earworm caterpillars have been part of Megan’s research on plant-caterpillar interactions. It is very rare for caterpillars to be truly carnivorous, but not uncommon for herbivorous caterpillars to be cannibalistic under certain circumstances, such as overcrowding or high levels of plant chemical defense. While the adult moth’s role in pollination is still unclear, they do feed on plant nectar.

Photo courtesy of Adrian Carper

Despite being Megan’s favorite part of the job, fieldwork isn’t always easy. This past season, temperatures soared to 106°F while surveying in Colorado National Monument. However, Megan stays motivated by the impact of her research. She knows the data she collects will directly help park staff protect public lands. "I love public lands," she says. "Knowing this research will support their conservation makes it incredibly rewarding."

Photo courtesy of Adrian Carper

When people see her in the field, net in hand, they often ask, "How are the bees doing?" Her answer is both sobering and hopeful.

Bee numbers are declining, but pollination systems are resilient. We still have a huge opportunity to make a difference. The time to act is now.

Dan Cariveau

Associate Professor, Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota Twin Cities

NPS projects: Bee and butterfly inventories at Voyageurs National Park, Mississippi National River and Recreation Area, St. Croix National Scenic Riverway, and Apostle Islands National Lakeshore

© Alison Cariveau

Dan Cariveau, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor at the University of Minnesota, where he leads the Cariveau Native Bee Lab. Dan’s path to researching insect pollinators began with a different taxon that sometimes act as pollinators—birds. After earning a degree in Wildlife Biology, he spent time in the Amazon studying songbirds and tracking down their nests. As he navigated the forest, he found himself captivated by the incredible diversity of tropical plants and their flowers. He began asking why flowers varied so much in color, shape, scent, and size, and realized that the answer lay in their 120-million-year evolutionary dance with pollinators. That question marked the beginning of a career now dedicated to understanding native bees and the habitats they depend on.

© Marissa Chase

Dan’s lab focuses on native bee ecology and prairie restoration. Bees exhibit an extraordinary range of life strategies—solitary, social, parasitic, ground-nesting, and stem-nesting—but all rely on nectar and pollen. "There is no other group of animals so tied to flowers," Dan explains. His lab uses pollinators to understand how diverse ecosystems develop and persist. They also research how restoration can support those systems by reinforcing the intricate relationships between plants and bees.

© Kylee Nissen

While Dan enjoys the occasional chance to roam a prairie in search of bees and blooms, his favorite part of the job is mentoring. "I love working with graduate students and postdocs. They bring a lot of passion and intelligence to the field," he says. He finds it deeply rewarding to help students develop as scientists and watch their careers unfold. He also values collaborations with conservation practitioners who help translate research into on-the-ground action. Seeing landscapes through their eyes adds a new dimension to his work, blending scientific insight with land-based knowledge.

© Kylee Nissen

Much of Dan’s time is now spent managing grants and supporting students, rather than directly collecting data. While he sometimes misses the opportunity to dive deep into a single research question, he values the variety and reach of his current role. What keeps him going is the sense of discovery that comes with every project. New findings continue to emerge, including his lab’s recent documentation of nearly 520 bee species in Minnesota. His team is using that knowledge to inform efforts to build and maintain pollinator habitats in the face of widespread insect declines.

There are so many species of bees, and for most, we know surprisingly little. We haven’t even found the nests of many of them. We’re still discovering new species. What’s especially exciting is how much interest and support we’re seeing from the public. I really enjoy sharing our findings about these little, mysterious creatures.

Transcript

Bumble bees enter and exit a small hole in an urban building.

- Duration:

- 30.631 seconds

Rusty-patched bumble bees (Bombus affinis) are a federally endangered species that sometimes inhabit urban areas. A collaborative study between the Cariveau Lab and multiple government agencies in 2020 documented a nest of this rare species in the insulation of a home! The researchers placed a piece of tape at the nest entrance so they could easily find it. Bumble bees use visual cues to find their nest entrances, so as the workers returned, they curiously investigated this new addition.

Nina Crawford

Ph.D. Student, University of Wyoming

NPS projects: Bee and butterfly inventories at Devils Tower National Monument, Mount Rushmore National Memorial, Wind Cave National Park, and Jewel Cave National Monument

Photo courtesy of Nina Crawford

Nina Crawford, a Ph.D. student at the University of Wyoming, is studying pollinators in national parks for her doctoral dissertation. Nina’s journey into pollinator research began during her undergraduate years when her professor, Dan Cariveau, encouraged her to join his lab. At the time, she knew she loved research but hadn’t found a focus that truly resonated with her yet. That changed when she joined the Cariveau Native Bee Lab at the University of Minnesota, where she was tasked with cleaning and pinning bee specimens. As she worked with the specimens, her curiosity grew and ultimately led her to explore bumble bee distribution as an independent research project.

NPS / Michelle Boone

After completing her undergraduate degree, Nina spent a year with the NPS I&M Program as a Scientists in Parks intern collecting pollinator data from parks across the country. Now in the second year of her graduate program, Nina studies the effects of land management activities, such as herbicide application and prescribed fire, on pollinator populations in national parks across the northern Great Plains. Her research spans multiple groups of pollinators, from bees to butterflies, offering her a front-row seat to the intricate dynamics of pollinator communities.

Photo courtesy of Nina Crawford

Beyond the excitement of fieldwork, Nina’s favorite part of her job is the people she meets. From museum curators to taxonomists, she finds herself surrounded by intelligent, passionate individuals that are dedicated to understanding the smallest creatures who keep ecosystems thriving.

Photo courtesy of Nina Crawford

During long days in the field or the uphill battle of securing research funds, when things get tough Nina finds motivation in the trailblazing scientists who came before her and the desire to give back. “I’m doing research for the women that will come after me because I have been so well served by the women that have come before me,” she says.

For those looking to help pollinators, Nina emphasizes that small, simple actions can have a significant impact.

You don’t need fancy bee hotels or elaborate setups—just planting a variety of flowers that bloom from spring to fall can make a big difference. And if you feel inspired to become more involved in conservation efforts, there are some really amazing citizen science platforms you can look into like Monarch Joint Venture and Bumble Bee Atlas.

NPS / Michelle Boone

Jennifer Thieme

Science Manager, Monarch Joint Venture

NPS projects: Monarch inventories at San Antonio Missions National Historical Park and Padre Island National Seashore.

© Kristen Nelson

Jennifer Thieme, M.S., coordinates Monarch Joint Venture’s research and monitoring projects throughout the United States. Monarch Joint Venture is a non-profit organization whose mission is to deliver habitat conservation, education, and science to protect monarchs and their migration. Jennifer's journey into pollinator conservation began in grasslands. After earning her undergraduate degree, she dove into a series of bird-focused research projects, working alongside graduate students and doctoral researchers. These experiences deepened her connection to grassland ecosystems and laid the groundwork for a career centered around conservation and scientific monitoring. In 2018, she brought this expertise to Monarch Joint Venture, where she now serves as the organization’s Science Manager.

At Monarch Joint Venture, Jennifer focuses primarily on monarch butterflies, a species she finds both fascinating and emblematic of hope. "A female monarch can lay up to 400 eggs in her lifetime," she explains. "Given the right conditions, their populations can rebound impressively." For Jennifer, this fact is a reminder that conservation efforts matter. When people create healthy habitats, monarchs are ready to respond.

Photo courtesy of Haylie Wilcox (left), NPS / Michelle Boone (right)

A female monarch can lay up to 400 eggs in her lifetime, such as this egg found on showy milkweed. A monarch caterpillar feeds on milkweed, its sole food source. Milkweed contains toxins that don’t harm the caterpillar but make it toxic to predators. Dozens of milkweed species are native to the U.S., including common, butterfly, swamp, and showy milkweed. To support monarchs, it’s best to plant native milkweed, avoiding non-native species like tropical milkweed.

© 2016 Jee & Rani Nature Photography (left), NPS (right)

Non-native species such as tropical milkweed (left) can alter migration and breeding patterns of monarchs in temperate regions and may host higher amounts of the pathogen OE when they do not die back in the winter. To help support monarchs, plant any of the dozens of species of native milkweeds, such as showy milkweed (right).

© Jennifer Thieme

What drew Jennifer to pollinators is their remarkable ability to uplift entire ecosystems. By supporting pollinators, she notes, we also support native plants, birds, and even improve water quality and carbon storage. The ripple effect is powerful. Now, her favorite part of the job is the collaborative energy of pollinator conservation work. Whether she's working with fellow scientists, partner organizations, or land stewards, she thrives in the shared momentum of collective action. "People are eager to share successes and learn from each other's experiences, all in the name of conservation," she says.

The public might be surprised to learn that monarch conservation goes far beyond planting milkweed. Jennifer’s work involves analyzing large-scale datasets that help shape regional and national conservation strategies. She finds motivation in transforming data into meaningful action, knowing that each project supports partners in addressing critical conservation challenges.

Whether you enjoy beautiful landscapes, discovering a caterpillar under a leaf, birding, or simply 'bee-ing' outdoors, you’re already connected to pollinators. They are deeply woven into the ecosystems we value, and they’re surprisingly easy to support through everyday conservation actions.

© Jennifer Thieme

Michelle Boone

Pollinator Project Manager, NPS I&M Program

NPS projects: All I&M pollinator inventories! Eleven projects that span 26 park units (as of 2025).

© Michelle Boone

Michelle Boone, Ph.D., oversees pollinator inventory projects and serves as a bee and butterfly subject matter expert in the NPS I&M Program. Michelle’s path to pollinator research was shaped by unexpected opportunities that led her to a field she loves. As an undergraduate, she imagined working with large mammals, particularly wolves or other predators. But when graduate programs in wildlife biology didn’t pan out, a connection led her to a newly formed native bee lab in the University of Minnesota Entomology Department. Before she knew it, she was studying bumble bee detection and occupancy patterns to inform monitoring efforts for the federally endangered rusty-patched bumble bee. "Sometimes you just have to take opportunities that lead to the unknown. You might end up somewhere amazing you never could have imagined!" she says. After graduating, Michelle moved across the country to study western monarch habitat needs and breeding phenology in the Pacific Northwest.

© Michelle Boone

Examples of Michelle's post-doctoral research studying monarchs (top row) and graduate work studying rusty-patched bumble bees (bottom row) prior to joining the NPS. Top row: Weighing and measuring an adult monarch (left), field enclosures in eastern Oregon containing monarch caterpillars being studied (center), and a monarch pupa nearly ready to emerge as an adult (right). Bottom row: A rusty-patched bumble bee collected from a Minnesota home after the colony had died (left), a rusty-patched bumble bee rests on Michelle's finger (center), and a partially dissected bumble bee pupal case (right). A special federal permit is required to handle endangered species, such as the rusty-patched bumble bee.

Now, Michelle oversees eleven pollinator inventory projects across 26 national park units in 14 states. While she no longer conducts research herself, she plays a crucial role in supporting those who do. Her favorite part of the job is collaborating with researchers and park staff from across the country. She manages agreements, ensures that pollinator inventory projects are properly planned and implemented, and makes sure that the science is rigorous and will answer park management questions. Though much of her work takes place behind a desk, she cherishes opportunities to visit parks, meet staff in person, and see firsthand the landscapes she helps support.

NPS / Michelle Boone

Michelle’s journey from field researcher to project manager has given her a unique perspective on the importance of administrative support in science. "When it’s a beautiful day outside and I’m stuck at my computer, my back hurts, and I’m drafting my billionth task agreement, I stay motivated by thinking about who I am supporting—the researchers, the parks, and the pollinators," she explains. She understands how crucial it is to secure funding and keep projects running smoothly, knowing that even minor delays can have real consequences for researchers and conservation efforts.

Photo courtesy of Lusha Tronstad

For those looking to support pollinators, Michelle emphasizes that conservation goes far beyond honey bees. North America is home to over 3,700 native bee species, along with pollinating flies, beetles, birds, mammals, butterflies, and moths. These species rely on native, pesticide-free plants that bloom in succession throughout the year, as well as access to undisturbed soil and hollow stems for nesting and overwintering.

One of the most challenging aspects of pollinator conservation is changing our personal perceptions of landscape aesthetics. A perfectly manicured lawn does not support pollinators, while a landscape with native plants and undisturbed areas does!

Protecting the Future of Wild Spaces

Pollinators may be small, but their impact on national park ecosystems and surrounding landscapes is immense! Thanks to the dedication of researchers, we are learning more about how to protect them every day. The work of these scientists helps safeguard not only individual species but the intricate networks that sustain life across our parks. National park lands have some of the highest-quality, intact habitats left in the country, offering crucial refuge for pollinators amid widespread habitat loss across much of the landscape. By supporting pollinators in protected areas, we give treasured landscapes and their species a chance to thrive.

Small changes, like reducing pesticide use and letting wildflowers grow, can help create healthier environments for pollinators so they can continue to support the ecosystems we all depend on.

© Logan Rowe (left), Photo courtesy of Megan Blanchard (right)

Thank you to our partners for participating in interviews and providing photos!

Resources

Are you interested in getting involved in pollinator conservation? Check out these resources!

NPS / Sarah Whipple

Additional Partners

The NPS I&M Program collaborates with a variety of partner organizations, and we couldn't highlight them all in this article! Additional partners helping collect pollinator data in national parks include:

- Williams Lab, University of California Davis

- Crone Lab, University of California, Davis

- Winfree Lab, Rutgers University

- Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation

- Bush Lab, University of Texas San Antonio

- Mola Lab, Colorado State University

- U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Lab

By Michelle Boone and Christina Martin, I&M Program

Tags

- researchers

- pollinator research

- pollinator

- conservation

- resource management

- native bees

- bees

- butterflies

- monarch butterfly

- moths

- species inventory

- inventory and assessment

- inventory

- inventory and monitoring

- inventory and monitoring division

- apostle islands national lakeshore

- boston harbor islands national and state park

- colorado national monument

- devils tower national monument

- dinosaur national monument

- isle royale national park

- jewel cave national monument

- mississippi national river and recreation area

- minute man national historical park

- wind cave national park

- voyageurs national park

- mount rushmore national memorial

- pictured rocks national lakeshore

- saint croix national scenic riverway

- padre island national seashore

- san antonio missions national historical park

- sleeping bear dunes national lakeshore