Last updated: January 6, 2026

Article

Safe Harbor: The Maritime Underground Railroad in Boston

-

Safe Harbor: Introduction

Introduction with Ranger Shawn Quigley about Boston's Maritime Underground Railroad

- Duration:

- 1 minute, 50 seconds

The Liberator, December 31, 1858.

In December 1858 the headline "Escape of a Fugitive Slave from a Vessel in Boston Harbor"[1] appeared in multiple Boston newspapers, electrifying the city. The captain of a ship from Wilmington, North Carolina discovered a stowaway onboard named Phillip Smith. Determined to bring Smith back to North Carolina, the captain threatened to shoot anyone that attempted a rescue. He never got the chance though, because Philip Smith jumped overboard and swam to nearby Lovells Island. Frostbitten, he managed to hail a passing ship and make his way to abolitionists in Boston.

Like many other freedom seekers, Smith escaped slavery in a northbound ship. In fact, as a correspondent for a Wilmington, North Carolina newspaper wrote several years earlier, "it is almost an everyday occurrence for our negro slaves to take passage [aboard a ship] and go North."[2] Many enslaved individuals, especially those coming from states along the coast, utilized ships bound for northern ports to gain their freedom on the Maritime Underground Railroad.

The sailors…proposed to me to leave, in the centre of the cotton bales on deck, a hole or place sufficiently large for me to stow away in, with my necessary provisions.[3]

As William Grimes makes clear in his 1855 memoir, escaping via ship often meant hiding out in tight, uncomfortable places, hoping to avoid notice. For freedom seekers, the Maritime Underground Railroad provided its own unique risks and challenges. Because of these risks, freedom seekers had to be creative. They could secure passage by locating sympathetic ship captains or crews, bribing those working on the ship, or simply sneaking onboard and hiding. Enslavers went to extreme measures to prevent a loss of their "property" and would often search ships or smoke them out if they believed an enslaved person stowed away. After leaving the harbor, the journey could easily be derailed by bad winds, poor weather, or discovery.[4]

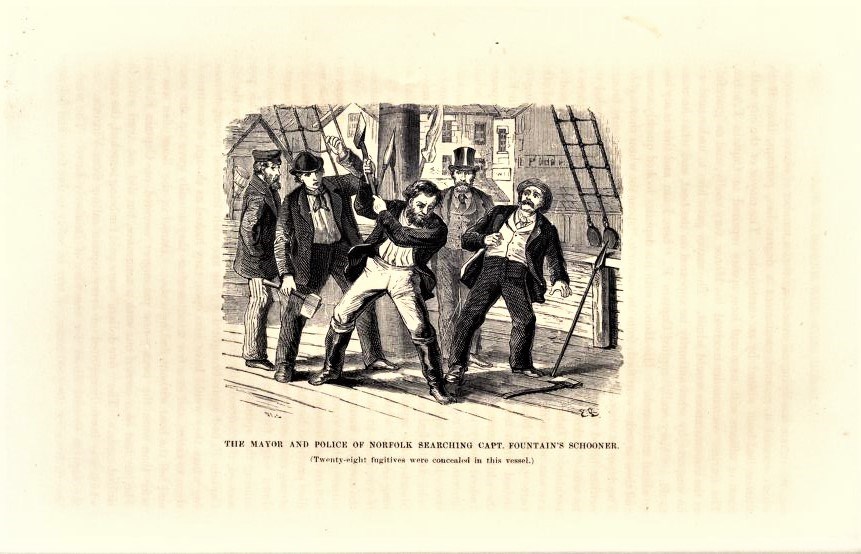

Still, William. The Underground Railroad. Courtesy of Dickinson College

Risks existed for the ship captains as well, regardless of whether they intentionally carried fugitives north. Ship captains caught with a fugitive on board faced tarnished reputations in the south, heavy fines, and, on some occasions, inhumane punishments. For example, Jonathan Walker, a native of Harwich, Massachusetts, had "S.S" for "Slave Stealer" branded on his hand following a failed attempt to assist fugitives escaping on the Maritime Underground Railroad.[5]

-

Safe Harbor: George

The story of George, a freedom seeker discovered in Boston Harbor.

- Duration:

- 2 minutes, 15 seconds

The Emancipator, October 7th 1846.

The Case of George

Unlike Walker, many ship captains that traded with the South endeavored to return stowaways at all costs. For example, in September 1846, the crew of the Ottoman, a ship from New Orleans, discovered a stowaway named George within Boston Harbor. Following this discovery, the captain of the Ottoman, James Hannum, took George under guard to Spectacle Island.

Captain Hannum stopped in one of the island's hotels for a "drop of consolation." While the captain grabbed his drink, George escaped from the guard, stole Hannum’s small boat, and took off for South Boston. Captain Hannum immediately realized what happened and grabbed another boat to give chase. Describing the pursuit first by boat, then on foot, Hannum wrote "we took off after him, through corn-fields and over fences till finally after a chase of two miles I secured him just as he reached the bridge."[6]

Word of George's arrest spread quickly among Boston's abolitionist community and they obtained a warrant for Hannum's arrest under the charges of kidnapping. Knowing he had to act quickly, Hannum located the Niagara, a ship bound for New Orleans to take George back to slavery. As he transferred George to the Niagara, Hannum realized that abolitionists had acquired a boat and were quickly gaining on his ship. Describing the scene Hannum wrote

No sooner had I left the bark than I discovered a steamer making directly for us. Knowing she could chase but one, I steered a course opposite to the Niagara…Bayonets glistened in all parts of the boat; darkies were there of every hue, crying out ‘run him down,’ ‘fire into him.’[7]

Unfortunately, the abolitionists followed Hannum's ship instead of the Niagara and were not able to secure George’s freedom.

Following the failed attempt to rescue George, Boston's abolitionists called for a mass meeting at Faneuil Hall to protest the "shameful outrage upon the sacred rights of humanity." Signifying the importance of the moment, John Quincy Adams, the seventy-nine-year-old former United States president, served as president of the meeting. Giving brief remarks because of his age, Adams told those in attendance

It is a question whether this Commonwealth is to maintain its independence as a state or not. It is a question whether your and my native commonwealth is capable of protecting the men who are under its laws or not.[8]

Following speeches from Charles Sumner, Wendell Phillips, and Samuel Gridley Howe, those in attendance resolved to create a committee of vigilance. This 1846 organization preceded the much larger Boston Vigilance Committee created in the aftermath of the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law.

-

Safe Harbor: Austin Bearse

The story of Austin Bearse, maritime slaver turned active abolitionist.

- Duration:

- 2 minutes, 15 seconds

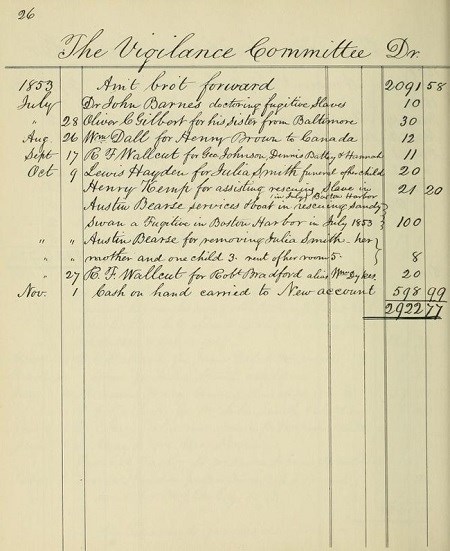

Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston. Courtesy of Cape Cod Community College

Austin Bearse

By the passing of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Boston's reputation as a crucial stop on the Underground Railroad had been firmly established. One of the best sources available to help explore this narrative is the account book of the Boston Vigilance Committee, an organization that acted as the financial backbone of the Underground Railroad in Boston. The entries in the Vigilance Committee records not only identify the names of individuals and their level of involvement, but also provide insight into the Maritime Underground Railroad in Boston. For example, in October 1853, Austin Bearse received one hundred dollars for "services in rescuing Sandy Swan, a fugitive in Boston Harbor in July 1853."[9] Born in Barnstable Massachusetts Austin Bearse proved to be an essential leader in Boston's Maritime Underground Railroad.

Prior to his work with the Vigilance Committee, Bearse earned a living as a mate on ships that traded throughout the east coast. Part of this trade included transporting enslaved individuals, giving Austin Bearse firsthand experience with the evils of slavery. As he wrote in his memoir Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days:

It used to be my business to pull off the hatches and warn [the slaves] that it was time to separate, and the shrieks and cries at these times were enough to make anybody’s heart ache…Because I no longer think it right to see these things in silence, I trade no more south of Mason and Dixon's line.[10]

By the 1830s Austin Bearse identified as an ardent abolitionist and used his maritime skills to assist freedom seekers.

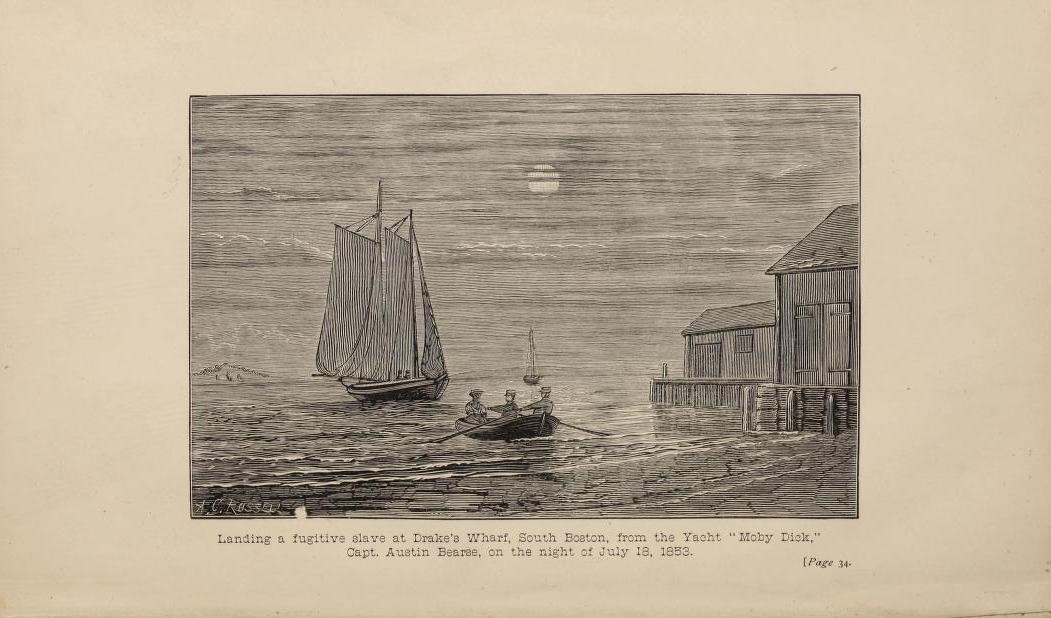

The Liberator, June 18th 1852.

No longer involved in trade with the south, Austin Bearse still found employment in the maritime industry. He owned a boat called the Moby Dick, a vessel that could be hired by Bostonians for daylong fishing excursions and harbor cruises. At night though, Bearse used the Moby Dick to help stowaways gain their freedom from southern ships. For example, in September 1854 abolitionists learned of a stowaway on the Sally Anne, a ship docked near Castle Island. Bearse sprang to action and took the Moby Dick to rescue the fugitive. Pulling alongside the Sally Anne, the captain immediately threatened violence, telling Bearse that if he attempted to get the fugitive he would "send you into eternity damned quick."[11] Regrouping at Long Wharf and unable to find anyone to immediately assist him, Bearse took bold action. As he wrote in his memoir,

Knowing it was daylight soon I had to lay a plot. I took a dozen old hats and coats and fastened them up to the rail in my yacht, which gave me the appearance of having so many men; I then went down back alongside the schooner again and told the captain I had now come prepared, and he had better give up the fugitive and save bloodshed. After parleying a little while he agreed to put the slave in my boat.[12]

Thanks to the cunning efforts of and quick thinking of Bearse, the fugitive successfully made his way to Canada.

Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days courtesy of Harvard University

Committees of Reception

Though in this previously mentioned case, Bearse acted alone out of necessity, he regularly operated among a network of activists in Boston assisting those on the Maritime Underground Railroad. When word of a stowaway reached Boston’s antislavery community, a "Committee of Reception" often formed to meet them. According to abolitionist George Putman, these "Committees of Reception" would have "the food and clothing necessary-even at midnight-and have on the wharf- a carriage ready to take the slaves well toward the Canadian border long hours before the enraged captain of the ship could swear out the necessary warrants and have the officers on the trail."[13]

Women served as critical members of these "Committees of Reception." As Vigilance Committee member Thomas Wentworth Higginson recalled, "The practice was to take along a colored woman with fresh fruit, pies, &c – she easily got on board & when there, usually found out if there was any fugitive on board; then he was sometimes taken away by night."[14] Captains rarely perceived Black women as threats, allowing these women to play crucial roles as operatives on the Maritime Underground Railroad.

-

Safe Harbor: Elisabeth Blakeley

The story of Elisabeth Blakeley, who sought freedom through Boston Harbor and on to Canada.

- Duration:

- 2 minutes, 7 seconds

The Brownies Book, November 1920.

Elisabeth Blakeley

Enslaved women also utilized the Maritime Underground Railroad to gain their freedom. A powerful example is the story of Elisabeth Blakeley, a freedom seeker from North Carolina. Fleeing a life of unimaginable horror, she snuck aboard a boat and hid herself in a narrow hole. According to Wendell Philips, when recalling the Blakeley story, "she lay while her inhuman master, almost certain she was on board the vessel, called out to her, 'you had better come out! I am going to smoke the vessel!' She tells: I heard him call, but my mind was liberty or death."[15]

Unable to find her, the ship left Wilmington and took four weeks to arrive in Boston. Escaping in the winter when she landed in the city, her feet badly frostbitten, she could barely stand. Despite all the hardship, Elisabeth Blakeley survived and began a new life as a free woman.

Her story and others exemplify the grave risks and potential reward of the Maritime Underground Railroad. As described by Frederick Douglass,

No man can tell the intense agony which is felt by the slave when wavering on the point of making his escape…All that he has is at stake, and even that which he has not…The life which he has, may be lost, and the liberty which he seeks, may not be gained.[16]

Despite the dangers and low odds of success, Elisabeth Blakeley, Philip Smith, and many other freedom seekers made their escape from slavery on the Maritime Underground Railroad and took their first steps on free soil in Boston.

Footnotes

[1] “Escape of a Fugitive Slave from a Vessel in Boston Harbor,” The Liberator, Dec. 31, 1858, p.2.

[2] Wilmington Journal, October 19, 1849, p.3, Cited in: David Cecelski, "The Shores of Freedom: The Maritime Underground Railroad in North Carolina 1800-1861," The North Carolina Historical Review, vol. 71, no. 2 (APRIL 1994), p.1.

[3] Grimes, William. Life of William Grimes, the Runaway Slave. Written by himself. New York, 2001. P.51, docsouth.unc.edu/neh/grimes25/grimes25.html#grime51.

[4] *For more information regarding the risks freedom seekers faced when attempting to stowaway on a ship, see David Cecelski's article, "The Shores of Freedom: The Maritime Underground Railroad in North Carolina 1800-1861."

[5] For more on Jonathan Walker see: A Short Sketch of the Life and Services of Johnathan Walker, The man with a Branded Hand.

[6] “Capt. Hannum to the Slaveholders!!” The Emancipator, Oct. 7, 1846.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Address of the Committee Appointed by a Public Meeting, Held at Faneuil Hall, September 24, 1846, For the Purpose of Considering the Recent Case of Kidnapping from Our Soil, and of taking Measures to Prevent the Recurrence of Similar Outrages. White and Potter Printers, 2008, P.2. Archive.org archive.org/details/addressofcommitt00bost/page/2/mode/2up.

[9] Jackson, Francis. Treasurers Accounts: The Boston Vigilance Committee. Bostonian Society, 2011, P. 26. Archive.org archive.org/details/drirvinghbartlet19bart/page/26/mode/2up.

[10] Bearse, Austin. Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days. Warren Richardson, 2008, P.20. Archive.org archive.org/details/reminiscencesfu00beargoog/page/n20/mode/2up/search/trade.

[11] Ibid, P.36.

[12] Ibid, P. 36.

[13] Putnam, George. “Letter to William Siebert” November 5, 1893. Ohiomemory.org https://www.ohiomemory.org/digital/collection/siebert/id/16770/rec/15.

[14] Sandra Harbert Petrulionis, "Fugitive Slave-Running on the Moby Dick: Captain Austin Bearse and the Abolitionist Crusade," Resources for American Literary Study 28 (2003): 69.

[15] Bearse, Austin. Reminisces of the Fugitive Slave Law Days. Warren Richardson, 2008, P.31. Archive.org archive.org/details/reminiscencesfu00beargoog/page/n20/mode/2up/search/trade.

[16] Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom. Auburn: Miller, Orton and Mulligan, 2017. P. 284. Archive.org archive.org/details/DKC0119/page/n283/mode/2up/search/intense+agony.