Last updated: January 12, 2026

Place

Spectacle Island

Boston Harbor Now

Beach/Water Access, Benches/Seating, Cellular Signal, Dock/Pier, Ferry - Passenger, First Aid Kit Available, Food/Drink - Snacks, Historical/Interpretive Information/Exhibits, Information, Information - Maps Available, Information - Ranger/Staff Member Present, Junior Ranger Booklet Available, Picnic Shelter/Pavilion, Picnic Table, Restroom, Scenic View/Photo Spot, Toilet - Flush, Water - Bottle-Filling Station, Water - Drinking/Potable

Located four miles from downtown Boston, Spectacle Island is a true example of trash turned into treasure. Spectacle Island features five miles worth of trails, panoramic views of the harbor, and a rich history.

Throughout its lifetime, Spectacle Island has served many purposes for many different people. Local Indigenous communities have honored and stewarded the island for thousands of years. Prior to European colonization of the area, Indigenous Peoples primarily used the island seasonally from spring to fall. One piece of evidence of this early presence includes shell middens, which are large mounds of discarded shell pieces along with other scraps.

With the arrival of European settlers in the 1600s, so too came smallpox. The town of Boston opened a smallpox quarantine hospital on Spectacle Island in 1717. Ships coming into Boston known to have smallpox were required to stop at Spectacle to quarantine. The hospital operated for 20 years before it was moved to Rainsford Island.1

Spectacle Island also housed two hotels for about ten years, between around 1846 and 1857. These hotels were later shut down after a police raid due to illegal gambling.2

During the years of the Underground Railroad, Spectacle Island served an integral role in the story of freedom seeker George's escape from slavery.

In September 1846, the crew of the Ottoman, a ship from New Orleans, discovered a stowaway named George within Boston Harbor. Following this discovery, the captain of the Ottoman, James Hannum, took George under guard to Spectacle Island. Captain Hannum stopped in one of the island's hotels for a "drop of consolation." While the captain grabbed his drink, George escaped from the guard, stole Hannum's small boat, and took off for South Boston. Captain Hannum immediately realized what happened and grabbed another boat to give chase. Describing the pursuit first by boat, then on foot, Hannum wrote: "we took off after him, through corn-fields and over fences till finally after a chase of two miles I secured him just as he reached the bridge."3

Word of George's story spread quickly among Boston's abolitionist community and they obtained a warrant for Hannum's arrest under the charges of kidnapping. Knowing he had to act quickly, Hannum located the Niagara, a ship bound for New Orleans that would take George back to enslavement. As he transferred George to the Niagara, Hannum realized that abolitionists had acquired a boat and were quickly gaining on his ship. Describing the scene Hannum wrote, "No sooner had I left the bark than I discovered a steamer making directly for us. Knowing she could chase but one, I steered a course opposite to the Niagra…Bayonets glistened in all parts of the boat..."4 Unfortunately, the abolitionists followed Hannum's ship instead of the Niagra and were not able to secure George's freedom.

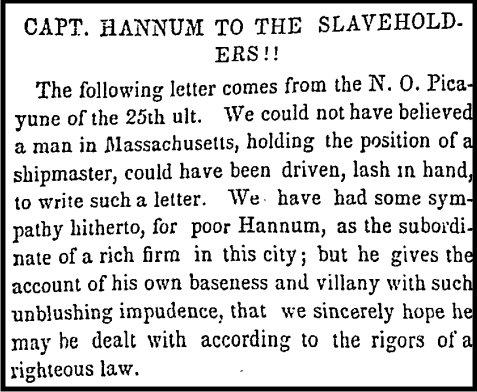

A newspaper clipping describing a letter written by Capt. Hannum. (Credit: The Emancipator, New York, New York, Oct. 7, 1846.)

In 1857, a man named Nahum Ward purchased the island in order to build a horse-rendering plant. This plant opened shortly after the Civil War; it processed thousands of deceased horses from the city and converted hair, hides, hooves, and bones into other products.5

In the 1880s and 1890s, a fertilizer company and glue factory joined Ward's plant on Spectacle Island, with the addition of a grease-reclamation facility in 1911.6 At this time, many workers lived on the island. In 1889, 30 men worked on the island and 13 families lived on the island.7 By the 1920s, the community grew to more than 100 people and even included a school.8

In the 1920s, most of the existing plants and factories closed. By this time, only the grease-reclamation factory remained. This factory processed garbage, removing grease for soap before using the remaining waste as fill on the island. By the 1930s, the need for grease dwindled and so the final factory on Spectacle Island shut down.

Bostonians still needed a place for their waste. From 1935 to 1959, Spectacle Island became the city’s dump, bringing 350 tons of waste to the island daily.9 In this time, the island grew by almost 36-acres.10 The dump on Spectacle Island sat exposed, with trash seeping into the harbor, until 1992 when the "Big Dig" began in Boston. The Central Artery/Tunnel Project brought sediment to Spectacle Island to cap off the landfill and turn the island from an abandoned garbage dump to a park.

In 2006, after years of work and the planting of thousands of trees and shrubs, Spectacle Island opened to the public. The island now serves as a great escape from the bustling city life of Boston, with hiking trails, a view from the highest point in Boston Harbor, a swimming beach, and more to explore.

Learn More...

Footnotes

- Emily and David Kales, All About the Boston Harbor Islands (Cataumet, MA: Hewitts Cove Publishing Co., Inc., 1983), 22.

- David Kales, The Boston Harbor Islands: A Story of Urban Wilderness (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2007), 73.

- "Capt. Hannum to the Slaveholders!!" The Emancipator, New York, New York, Oct. 7, 1846.

- "Capt. Hannum to the Slaveholders!!" 1846.

- Pavla Šimková, Urban Archipelago: An Environmental History of the Boston Harbor Islands (University of Massachusetts Press, 2021), 70-72.

- Šimková, Urban Archipelago, 70-72.

- M.F. Sweetser, King's Handbook of Boston Harbor (Boston: Moses King Corporation, 1889), 177.

- Šimková, Urban Archipelago, 91.

- Šimková, Urban Archipelago, 86.

- Kales, The Boston Harbor Islands, 129.