Rhythms of the SeasonsThe lives of people in Yosemite were closely tied to the cyclic rhythms of nature. Spring brought relief from the long, cold winter. Verdant growth of food plants and basket materials signaled the end of the winter. Deer began to move to higher elevations, bears and squirrels came out of hibernation, and high water made it more difficult to cross streams. Summer sent deer into the high country. Women harvested seeds, berries, and basket-making materials. They wove baskets for cooking, carrying water, and many other practical ceremonial purposes. Toward the end of summer, people set fires to encourage growth of plants useful to them and to clear the ground beneath oaks for easier acorn gathering. The incense cedar bark structure is a summer shelter. Local people call this an umacha, not a teepee. When it rained, people would go inside and build a fire on the dirt floor. Autumn was a time of acorn gathering. Stored in “chuckahs,” or granaries, women removed the acorns as needed. Women pounded the acorns and then leached the flour to remove the bitter tannins. They stored long strips of dried meat for use in the lean months of winter. Winter could be a time of harsh weather, eating stored foods, and perhaps gathering mushrooms to be shredded and dried. Some people moved to lower elevations to escape the cold.

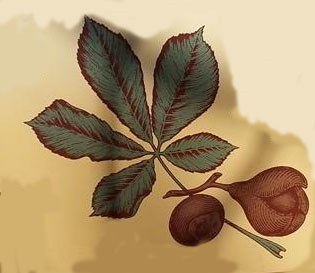

California BuckeyeMiwok people made tea from buckeye leaves and drank it to treat lung congestion. Buckeye nuts were crushed and applied as a poultice for hemorrhoids. While the nuts are poisonous, in times of scarcity they were put through a protracted process of roasting or boiling, mashing and leaching. The resulting mush was eaten for sustenance. A few Miwok people occasionally peeled and dried buckeye nuts and added several of them to black oak acorns. They were then pounded into flour, leached, cooked, and eaten. Since buckeye was a less-desirable food for most Miwok people, few have prepared it as food since the 1920s.

Canyon Live OakThe acorns of the canyon live oak were prepared just as black oak acorns were. Considered to the the “second-best” acorn (most people preferred black oak acorns) available to the Miwok, some people liked to mix live oak acorns in with those of the black oak. Today people occasionally gather live oak acorns, generally mixing them with black oak acorns in acorn mush. A number of local Indian people still make acorn mush for special occasions. Few still pound acorns with stone mortars and pestles; most use electric grinders. Some cook acorn mush in a pot on a conventional stove, but most contend that the mush tastes better when boiled with hot stones.

Creek DogwoodCreek dogwood was used in twined basketry by the Miwok. Some baskets were made with young, red, unpeeled, winter-gathered creek dogwood shoots (the bark of the creek dogwood turns bright red during winter months). Other twined baskets have yellow-green colored warp rods- these are creek dogwood shoots gathered in the spring or summer, or gathered in the winter and then soaked in water for more than a week, which causes the shoots to lose color. One utilitarian basket commonly made of creek dogwood was a seed beater, used to beat grass seeds into burden baskets. Prepared in various ways, the grass seeds were made into mush or eaten as a snack similar to “trail mix.” Many native grasses have now been replaced by exotic grasses, and fields of native grasses are difficult to find. Large-scale processing of native grasses for food by local Indian people ceased around 1900.

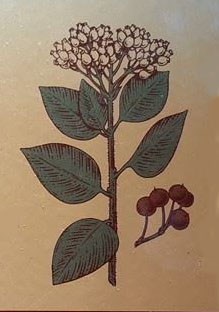

ManzanitaManzanita is the hardest wood in the Sierra Nevada, and was preferred for fires used to heat stones for cooking acorn mush, and to heat underground ovens. Manzanita leaves were sometimes sucked by Miwok people to quench thirst, and as saliva production was stimulated. Dried manzanita berries were picked in late summer. They were cleaned and pounded into a course meal and placed on a closely woven winnowing basket. Cold water was poured over the meal and the resulting cider was caught in a watertight basket or carved oak bowl. The cider was prepared as a special treat for large gatherings, where it was sucked from a small brush made of grass or Cooper’s hawk tail feathers. Today a few people prepare manzanita cider for ceremonial gatherings, and other, using modern techniques, make manzanita-cider jelly and syrup.

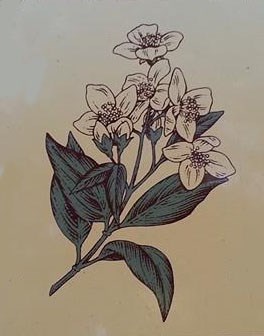

Mock OrangeThe straight, second-year shoots of mock orange bushes were used by the Miwok to make arrows. The dense wood is tough and resilient, but surrounds a white, pithy center, making a lightweight finished arrow. Miwoks arrows from the mid-19th century were highly valued and renowned for their excellent workmanship. Indian Canyon (to the right of Yosemite Falls and Lost Arrow Spire), known for its supply of this arrow wood, was also called leehameti by the Miwok, meaning “mock orange place.” By the end of the 19th century few Miwok people made or used bows and arrows, as rifles were preferred for hunting.

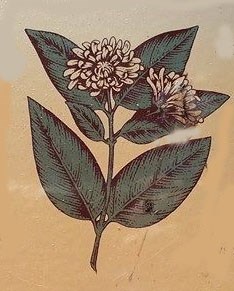

SpicebushSpicebush leaves and bark release an aromatic, citrus-like smell when they are bruised. Straight, second-year shoots which grow out of dense spicebush thickets were used by the Miwok for arrow shafts. The shafts produced were somewhat softer and less durable than those made from mock orange, but spicebush shafts were highly regarded for their light weight. By 1900, Yosemite Indian people were no longer using or making bows and arrows, though Chris Brown (“Chief Lemee”) demonstrated arrow making in Yosemite between 1930 and 1950. In the 1950s, Llyod Parker, a Miwok-Paiute resident of Yosemite, cut spicebush shafts for his grandsons to shoot with their toy bows, in lieu of finished arrows. Today, only a few Indian and non-Indian people make arrows from this plant. |

Last updated: November 17, 2018