NPS photo.

Introduction

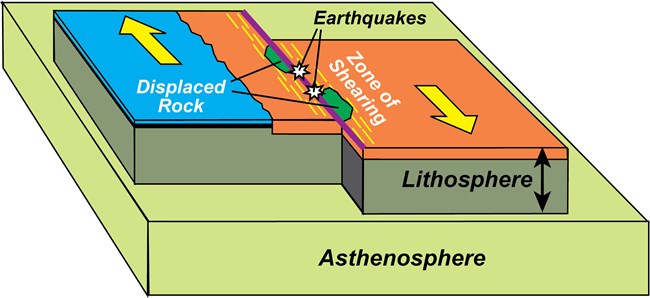

Where tectonic plates slip horizontally past one another, lithosphere is neither created nor destroyed. Instead, blocks of crust are torn apart in a broad zone of shearing between the two plates. Such boundaries are called transform plate boundaries because they connect other plate boundaries in various combinations, transforming the site of plate motion. The grinding action between the plates at a transform plate boundary results in shallow earthquakes, large lateral displacement of rock, and a broad zone of crustal deformation.

Perhaps nowhere on Earth is such a landscape more dramatically displayed than along the San Andreas Fault in western California. The landscapes of Channel Islands National Park, Pinnacles National Park, Point Reyes National Seashore and many other NPS sites in California are products of such a broad zone of deformation, where the Pacific Plate moves north-northwestward past the rest of North America. Virgin Islands National Park in the U. S. Virgin Islands is located on another transform plate boundary, where the Caribbean Plate is sliding past the oceanic part of the North American Plate.

Lateral Movement along a Transform Plate Boundary

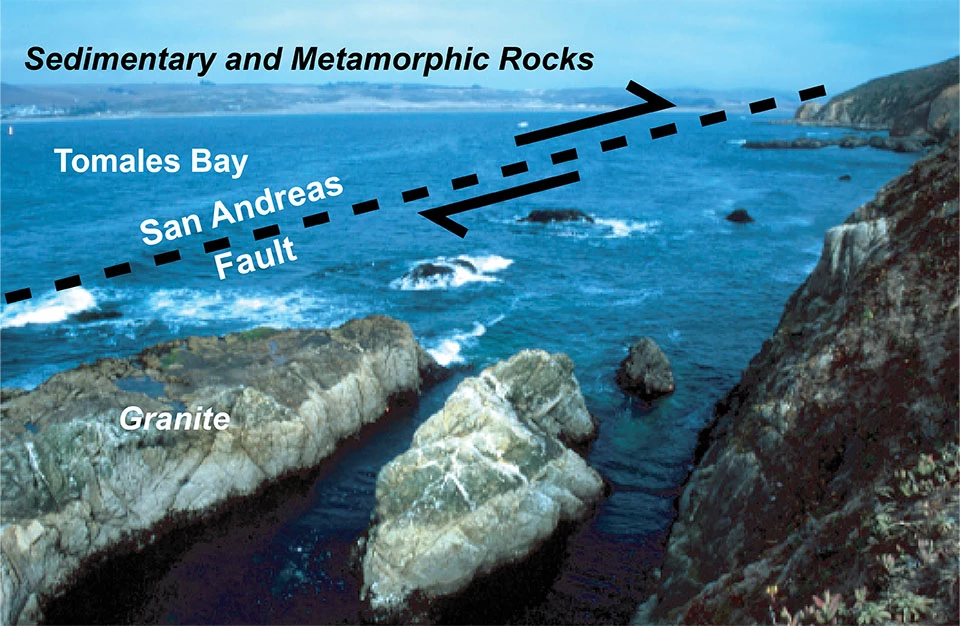

Point Reyes National Seashore, California. Tomales Bay is the surface expression of the San Andreas Fault, seen in the photo below. The granite rocks in the foreground are similar to those found in Yosemite National Park in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. They have been transported about 300 miles (500 kilometers) in a north-northwestward direction along the transform plate boundary. The sedimentary and metamorphic rocks across the fault line are similar to those found in Redwood National and State Parks on the North Coast of California. They were lifted out of the ocean as part of the accretionary wedge of an ancient subduction zone.

Left image

Tomales Bay.

Credit: Photo Courtesy of Robert J. Lillie.

Right image

Feature labels. (Click on arrows and slide left and right to see labels.)

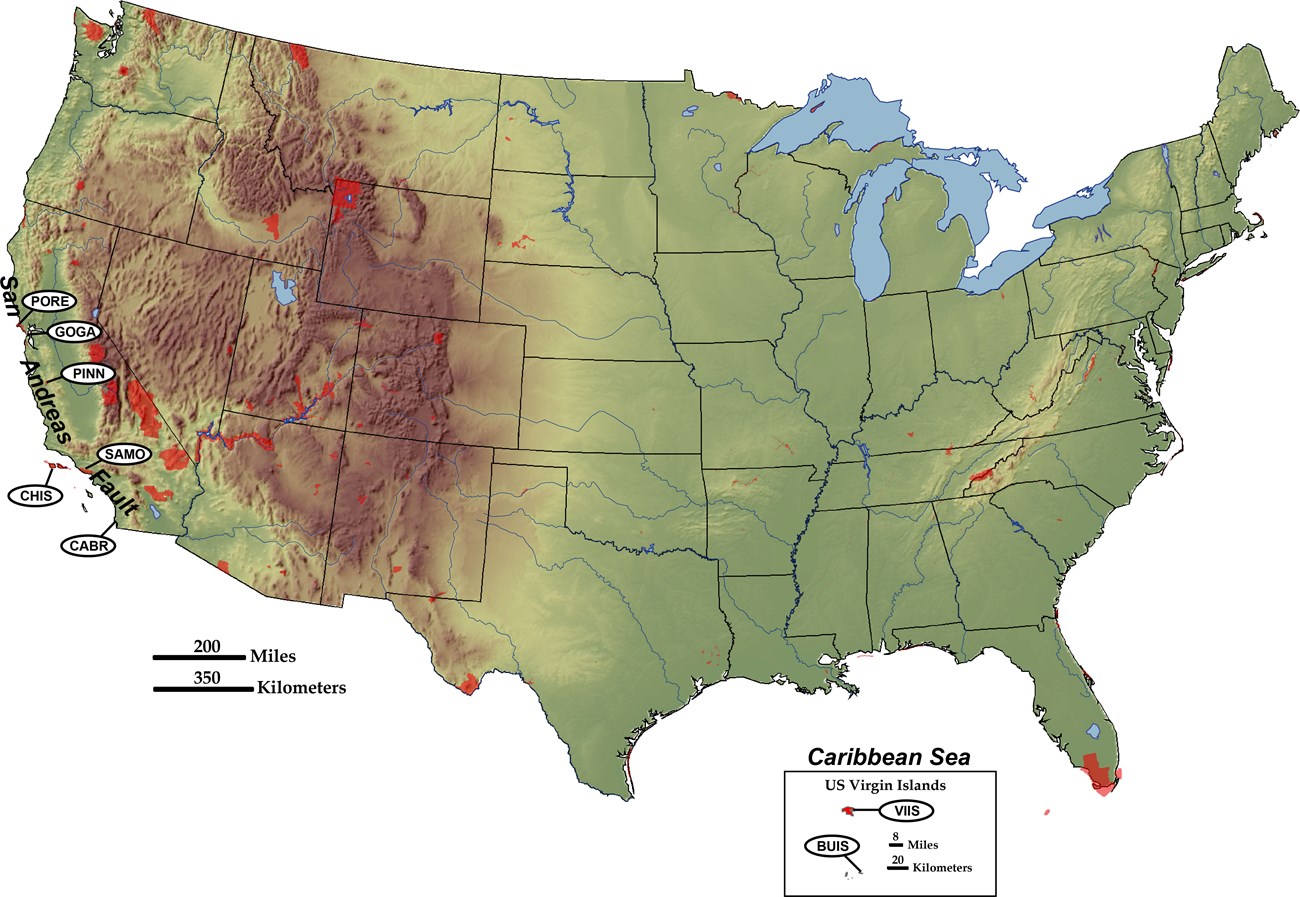

NPS Landscapes Developed at Transform Plate Boundaries

The San Andreas Fault is the transform plate boundary where a thin sliver of western California, as part of the Pacific Plate, slides north-northwestward past the rest of North America. In the Caribbean Sea, the U. S. Virgin Islands lie along a transform plate boundary where the small Caribbean Plate moves eastward past the oceanic part of the North American Plate.

Modified from “Parks and Plates: The Geology of our National Parks, Monuments and Seashores,” by Robert J. Lillie, New York, W. W. Norton and Company, 298 pp., 2005, www.amazon.com/dp/0134905172.

Transform Plate Boundaries—Continental

- CHIS—Channel Islands National Park, California [Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- CABR—Cabrillo National Monument, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- GOGA—Golden Gate National Recreation Area, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- PINN—Pinnacles National Monument, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- PORE—Point Reyes National Seashore, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- SAMO—Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, California—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

Transform Plate Boundaries—Oceanic

- BUIS—Buck Island Reef National Monument, U.S. Virgin Islands—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

- VIIS—Virgin Islands National Park, U.S. Virgin Islands—[Geodiversity Atlas] [Park Home]

Continental Transform—San Andreas Fault

California’s sheared-up landscape and earthquake hazards reflect the movement of the Pacific Plate past the edge of North America along a transform plate boundary that extends from the Mexican border to north of San Francisco. This feature includes the famous San Andreas Fault, responsible not only for destructive earthquakes, but also for the spectacular scenery of the San Francisco Bay area and other coastal regions of California.

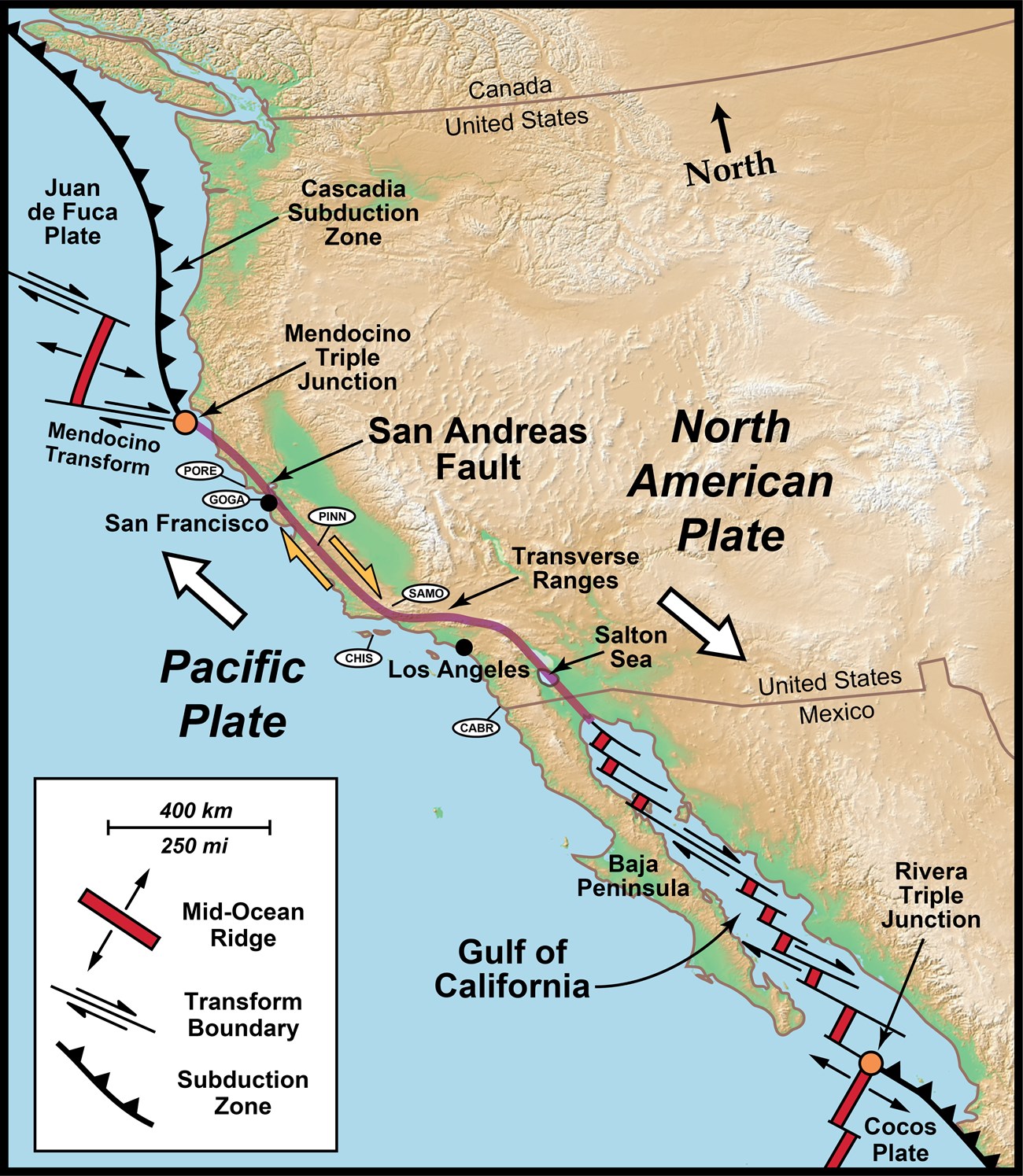

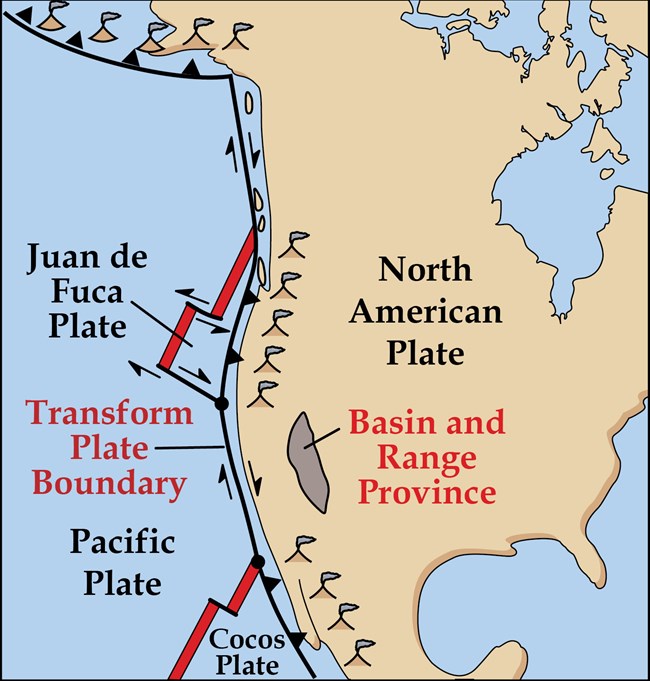

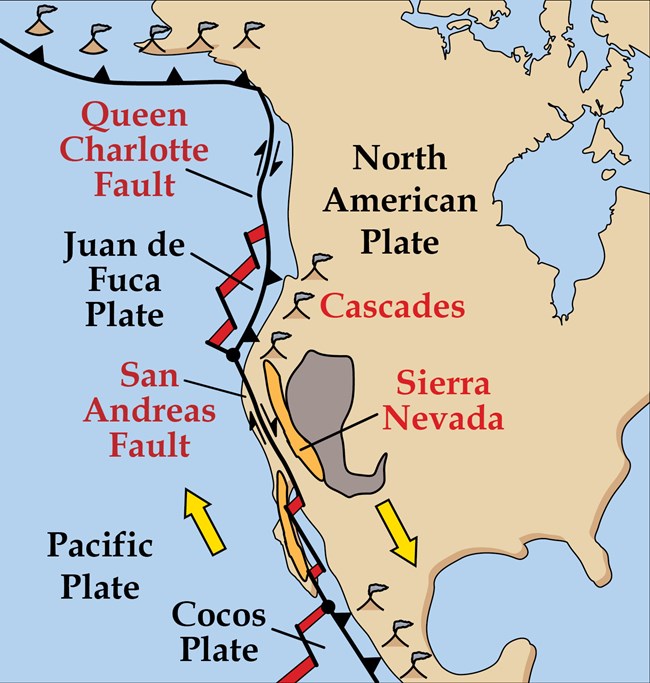

San Andreas Transform Plate Boundary

The Pacific Plate slides north-northwestward past the North American Plate along the San Andreas Transform Plate Boundary. The San Andreas Fault is responsible for most of the movement in western California, causing a sliver of the state to slide past the rest of the continent. In Mexico, a combinatiion of divergent and transform plate boundary motion is opening the Gulf of California, causing the Baja Peninsula to separate from the rest of Mexico. Letters in ovals are abbreviations for NPS sites listed above.

Modified from “Earth: Portrait of a Planet, by S. Marshak, 2001, W. W. Norton & Comp., New York.

Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and Pinnacles National Park present landscapes affected by the main line of movement, the San Andreas Fault. Channel Islands National Park, Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and Joshua Tree National Park are within the Transverse Ranges, a block of crust that rotated as a result of the shearing motion. Cabrillo National Monument south of San Diego also lies within the broad zone of deformation between the two plates.

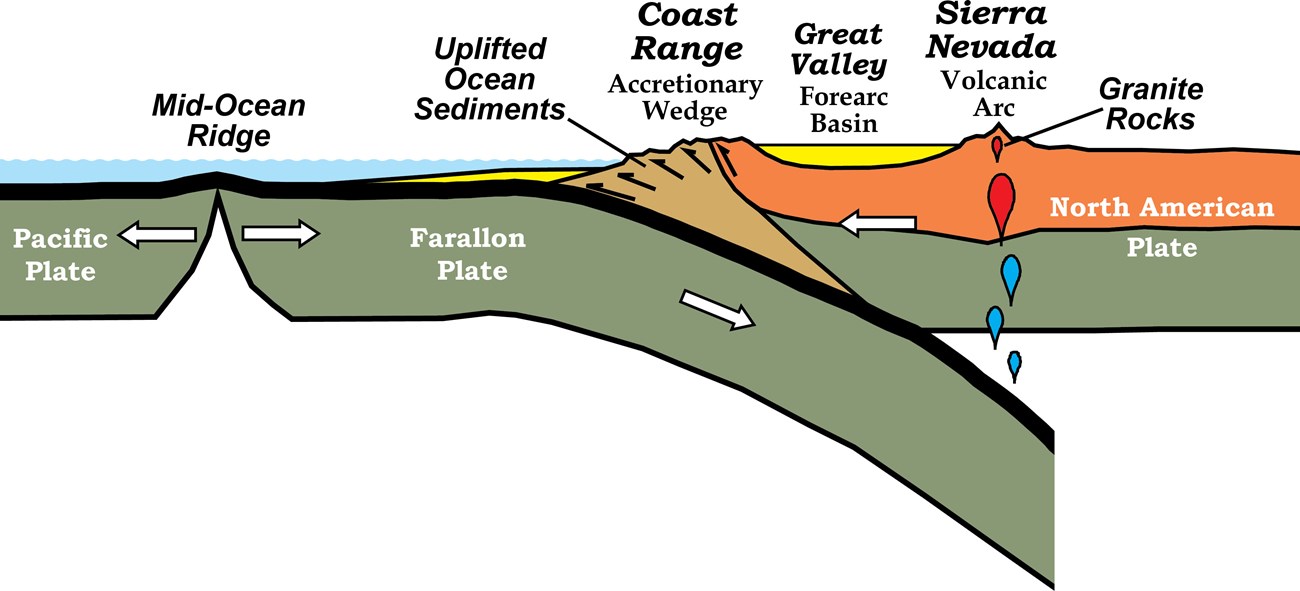

The transform plate boundary between the Pacific and North American Plates in western California formed fairly recently. About 200 million years ago, a large tectonic plate (called the Farallon Plate) started to subduct beneath the western edge of North America. This resulted in a line of volcanoes stretching all the way from what is now Alaska to Central America. Beginning about 30 million years ago, so much of the Farallon Plate was consumed by subduction that the Pacific and North American plates were in contact, forming the San Andreas transform plate boundary in western California. Over time, the San Andreas transform plate boundary has grown longer as the Farallon Plate split into two separate plates—the Juan de Fuca Plate on the north, and the Cocos Plate on the south. Remnants of the ancient volcanic mountain chain remain. In central and southern California, for example, the volcanoes have largely eroded away and massive areas of granite from the cooled magma chambers form portions of the Sierra Nevada Mountains, including Yosemite National Park.

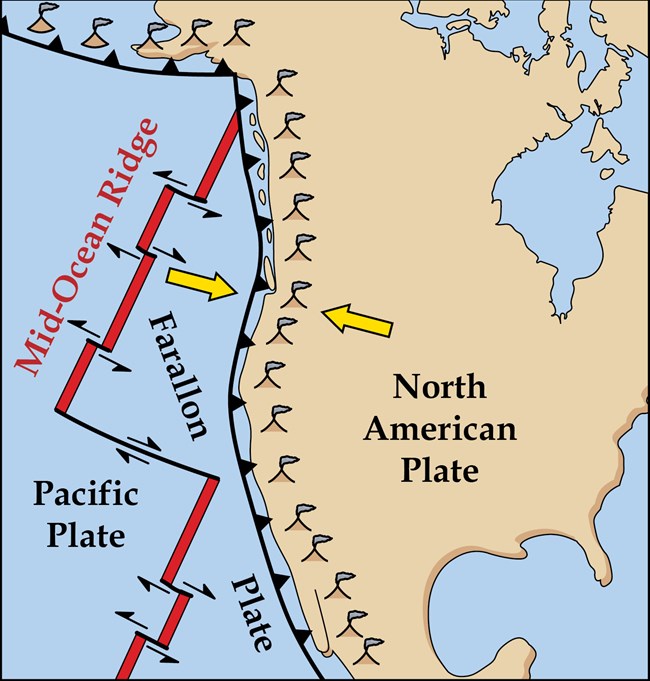

West Coast Tectonic Evolution

The San Andreas Transform Plate Boundary developed within the past 40 million years as a large portion of the Farallon Plate was subducted and the Pacific Plate made contact with the North American Plate in the California region.

40 Million Years Ago

Forty million years ago, a large tectonic plate, known as the Farallon Plate, was between the Pacific and North American plates. Subduction of the Farallon Plate beneath the entire West Coast created a line of volcanoes from Alaska to Central America.

20 Million Years Ago

As the mid-ocean ridge separating the Farallon and Pacific Plates entered the subduction zone, the Farallon Plate separated into the Juan de Fuca and Cocos Plates. A transform plate boundary developed where the Pacific Plate was in contact with the North American Plate and the volcanism ceased in central California. Farther east, the continent began to rift apart in the Basin and Range Province.

Images above modified from “Earth: Portrait of a Planet, by S. Marshak, 2001, W. W. Norton & Comp., New York.

Today

The Cascades are the modern volcanic arc developing where the Juan de Fuca Plate subducts beneath the North American Plate. The Sierra Nevada are the eroded remnants of the volcanic arc developed when the Farallon Plate subducted beneath the continent. The San Andreas Fault and Queen Charlotte Fault are transform plate boundaries developing where the Pacific Plate moves northward past the North American Plate.

The San Andreas Fault is just one of several faults that accommodate the transform motion between the Pacific and North American plates. The plate boundary is a broad zone of deformation with a width of about 60 miles (100 kilometers). Along much of the boundary, the bulk of the motion occurs along the San Andreas Fault. Point Reyes National Seashore and Golden Gate National Recreation Area are the only two NPS sites that are right on the San Andreas Fault. Other parks in the region, namely Pinnacles, Channel Islands and Joshua Tree national parks, Cabrillo National Monument and Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, reveal evidence of the shearing, rotation, and uplift that occurs within the broad zone of deformation between the two plates.

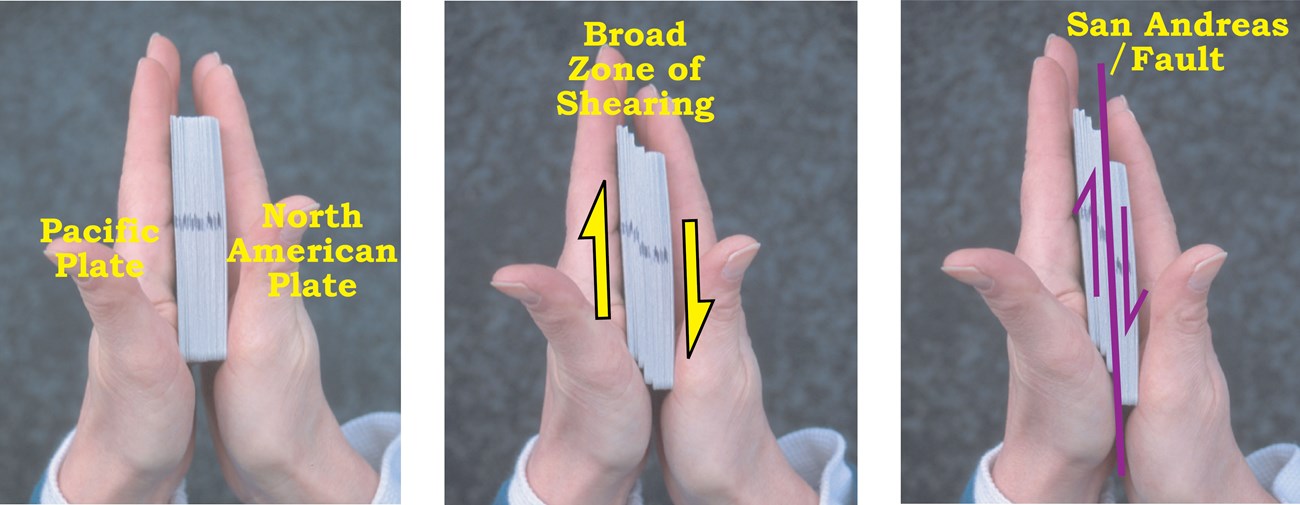

San Andreas Card Trick

Deformation along the transform plate boundary in California can be visualized by placing a deck of cards between your hands in a praying position. Imagine that your left hand is the undeformed Pacific Plate, your right hand the intact North American Plate. Notice what happens as you move your left hand away and slide your right hand toward you. The cards slip along their faces, forming a broad zone of shearing between your unaffected hands. For western California, each slipping card face would be a fault surface. The broad zone of transform motion between the Pacific and North American plates formed numerous slivers of mountain ranges with narrow valleys in between. The valleys are commonly due to erosion along individual fault lines. Sometimes the valleys are partially filled with water, as at Point Reyes National Seashore, where Tomales Bay and Olema Valley follow the main trace of the San Andreas Fault.

For western California, your left hand represents the rigid Pacific Plate, while your right hand is like the unaffected part of the North American Plate. |

As you slide your hands laterally past one another, a broad zone of shearing develops as several card faces slip. | Eventually the weakest card face (the San Andreas Fault) dominates within the broad transform plate boundary. |

Shear Zones

Modified from “Beauty from the Beast: Plate Tectonics and the Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest,” by Robert J. Lillie, Wells Creek Publishers, 92 pp., 2015, www.amazon.com/dp/1512211893.

The broad zone of shearing at a transform plate boundary includes masses of rock displaced tens to hundreds of miles, shallow earthquakes, and a landscape consisting of long ridges separated by narrow valleys.

U.S. Geological Survey.

The San Andreas Fault is just one of many active earthquake faults in a broad zone of shearing along the transform plate boundary in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Earthquakes on the San Andreas Fault can greatly upset cities along its length, including the San Diego, Los Angeles, and San Francisco/Oakland areas. But it’s interesting to note that this region is so heavily populated because of the same tectonic forces that sometimes shake it up with such violent consequences during earthquakes. These forces also create a sheared-up landscape that includes spectacularly beautiful coastlines and economically important harbors. Thousands of earthquakes over millions of years have built this landscape not only along the major fault line—the San Andreas Fault—but also on other faults within the broad zone of shearing between the Pacific and North American plates.

The cumulative movement within the broad San Andreas transform plate boundary has had dramatic effects on a landscape that initially developed as part of an ocean/continent subduction zone. For example, rocks found today in Point Reyes National Seashore north of San Francisco were originally part of the line of granite rocks formed beneath ancient subduction zone volcanoes. The plate motion has plucked the rocks from their original position and moved them more than 300 miles north-northwestward to their current position at Point Reyes. Other rocks in the San Francisco Bay Area were originally part of an accretionary wedge, similar to rocks found today in the coastal ranges of the Cascadia Subduction Zone in northern California, Oregon, and Washington.

San Andreas Fault Disrupts an Ancient Subduction Zone

Modified from “Earth: Portrait of a Planet, by S. Marshak, 2001, W. W. Norton & Comp., New York.

The transform plate boundary is a broad zone forming as the Pacific Plate slides northwestward past the North American Plate. It includes many lesser faults in addition to the San Andreas Fault.

Parks near the coast, including Point Reyes National Seashore, Golden Gate National Recreation Area, and Pinnacles National Park, contain volcanic and plutonic rocks that were plucked from the edge of the North American Plate and transported tens to hundreds of miles northwestward as part of the Pacific Plate.

Parks in the Sierra Nevada, including Yosemite, Kings Canyon, and Sequoia national parks, contain granite-type rocks that cooled within magma chambers beneath ancient subduction zone volcanoes.

National Park Service Sites (shown in red)

NP = National Park

NS = National Seashore

NM = National Monument

N&SP = National and State Parks

NRA = National Recreation Area

N Pres = National Preserve

Displacement of Rocks along San Andreas Fault

National Park Service sites along the transform plate boundary in California contain rocks formed during the earlier subduction that occurred in western North America. Like modern subduction zones, the region had an accretionary wedge (Coast Range), a forearc basin (Great Valley), and a volcanic arc (Sierra Nevada). The accretionary wedge rocks are found in Channel Islands National Park, Golden Gate and Santa Monica Mountains national recreation areas and Cabrillo National Monument. Point Reyes National Seashore and Joshua Tree National Park have granitic magma-chamber rocks of the eroded arc, and Pinnacles National Park preserves volcanic rocks. Rocks have been disrupted by shearing and other forces associated with the transform plate motion and, in some instances, transported northward a long distance from where they originally formed.

Modified from “Beauty from the Beast: Plate Tectonics and the Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest,” by Robert J. Lillie, Wells Creek Publishers, 92 pp., 2015, www.amazon.com/dp/1512211893.

Ancient Subduction Zone

Modified from “Beauty from the Beast: Plate Tectonics and the Landscapes of the Pacific Northwest,” by Robert J. Lillie, Wells Creek Publishers, 92 pp., 2015, www.amazon.com/dp/1512211893.

The magnitude 7.8 San Francisco Earthquake struck the morning of April 18, 1906. It caused extensive damage to the city, including fires that lasted for several days, and killed an estimated 3,000 people. The earthquake ruptured a large portion of the San Andreas Fault, including land that is now Point Reyes National Seashore and Golden Gate National Recreation Area. The Earthquake Trail at Point Reyes weaves back and forth across the fault line. Exhibits along the trail include the reconstruction of a fence that was offset 16 feet (5 meters) during the 1906 earthquake. Doing some quick math, one can appreciate how dramatically plate-tectonic forces can affect the landscape, even in our lifetimes. The average movement of the Pacific Plate past the North American Plate in California is about 2 inches (5 centimeters) per year. If a segment of the San Andreas Fault is “locked” for a century, then a large earthquake might result in 200 inches (2 inches/year x 100 years) of movement along the fault in less than a minute. The 16 feet (about 200 inches, or 5 meters) of offset along the fence line thus carries a powerful message. Every century or so a large earthquake is necessary to release stress accumulated along large segments of the San Andreas Fault that lock rather than slip smoothly. This type of knowledge helps us better design and site infrastructure, and develop disaster preparedness plans so that our families and communities are less at risk when earthquakes do strike.

Bay Area NPS Sites

National Park Service sites in the San Francisco Bay Area reveal a sheared-up, ancient subduction zone landscape developed along the San Andreas Fault.

Point Reyes National Seashore, California

USGS photo.

An offset fence line reveals the 16 feet (5 meters) of lateral ground breakage that occured as the San Andreas Fault suddenly let loose during the 1906 San Francisco Earthquake.

Photo courtesy of Robert J. Lillie.

Golden Gate National Recreation Area, California

Photo courtesy of Robert J. Lillie.

Layers of ocean sediment were squeezed and contorted as they were caught in the vise of the converging plates at the ancient subduction zone.

Photo courtesy of Robert J. Lillie.

Pillow basalt, formed as lava poured out on the ocean floor, was later scraped off the top of the subducting plate and thrust onto the edge of the continent.

Photo courtesy of Robert J. Lillie.

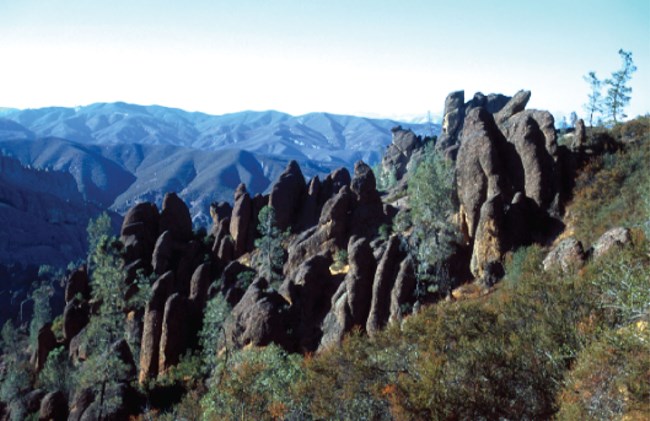

Parks in western California contain blocks of crust that have moved great distances north-northwestward along the San Andreas Fault. Volcanic rocks at Pinnacles National Park were displaced about 190 miles (305 kilometers), while granitic rocks of Point Reyes National Seashore have moved about 310 miles (500 kilometers).

A Transported Volcanic Landscape—Pinnacles National Park

The pinnacles are the eroded remnants of hardened volcanic breccia—slurries of mud and rock from explosive eruptions.

Photo by Robert J. Lillie.

This subduction zone landscape was later plucked from the edge of the North American Plate and transported nearly 200 miles northwestward along the San Andreas Fault.

Photo by Robert J. Lillie.

The Transverse Ranges north and east of Los Angeles are so named because they trend in an east-west direction, contrary to the northwest-southeast orientation typical of other ranges along the San Andreas transform plate boundary. They form due to north-south compression where the San Andreas Fault bends to an east-west orientation. The compressed and uplifted region includes the Santa Monica Mountains north of Los Angeles as well as the Channel Islands south of Santa Barbara.

National Park Service sites in the Transverse Ranges include Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area and part of Joshua Tree National Park. Channel Islands National Park includes five islands that are the tops of a mostly-submerged portion of the Transverse Ranges. The islands contain sedimentary layers and pillow lavas that formed on the ocean floor. Like many of the rocks that are caught up in the zone of transform motion between the Pacific and North American plates, the rocks at Channel Islands National Park were deformed as part of the accretionary wedge during earlier subduction of the Farallon Plate.

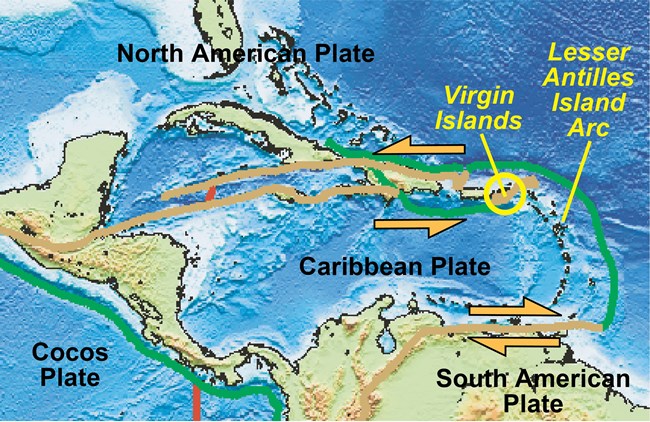

Oceanic Transform—Caribbean Region

The San Andreas Fault Zone is not the only active transform plate boundary with U. S. National Park Service sites. Southeast of Florida, the Caribbean Plate is sliding east-northeast about 0.8 inches (2 centimeters) per year relative to the North American Plate. Both plates are capped by oceanic crust. On the east, the North American Plate is subducting westward, forming volcanoes of the Lesser Antilles Island Arc. Transform boundaries occur on the north and south sides of the Caribbean Plate. The motion on the north is not pure transform; there is some convergence that contributes to uplift of the topography. The long mountain ridges and narrow bays in the region surrounding U. S. Virgin Islands National Park are a product of compression due to the convergence, in addition to lateral motion due to shearing along the transform plate boundary.

Carribean Tectonic Map

The Virgin Islands are in a broad zone where the landscape is being sheared up as the Carribean Plate slides eastward past the oceanic part of the North American Plate. Active volcanoes of the Lesser Antilles Island Arc form as the North American Plate subducts beneath the Caribbean Plate.

Seafloor topography map source: “Global sea floor topography from satellite and ship depth soundings,” 1997, by W. H. F. Smith and D. T. Sandwell, Science, v. 277, p. 1956-1962. Plate boundaries from The Plates Project, University of Texas Institute for Geophysics.

Virgin Islands National Park

Photo courtesy of the National Parks Conservation Association.

Figures Used

Related Links

Site Index & Credits

Plate Tectonics and Our National Parks

- Plate Tectonics—The Unifying Theory of Geology

- Inner Earth Model

- Evidence of Plate Motions

- Types of Plate Boundaries

- Tectonic Settings of NPS Sites—Master List

Teaching Resources—Plate Tectonics

Photos and Multimedia—Plate Tectonics

Geological Monitoring—Plate Tectonics

Plate Tectonics and Our National Parks (2020)

-

Text and Illustrations by Robert J. Lillie, Emeritus Professor of Geosciences, Oregon State University [E-mail]

-

Produced under a Cooperative Agreement for earth science education between the National Park Service's Geologic Resources Division and the American Geosciences Institute.

Last updated: February 11, 2020