|

Explore other places like gardens, country clubs, cemeteries, industrial buildings, private estates, public buildings, residential institutions, churches, subdivsions, city planning, campuses, fairs, and the many, many park designs.

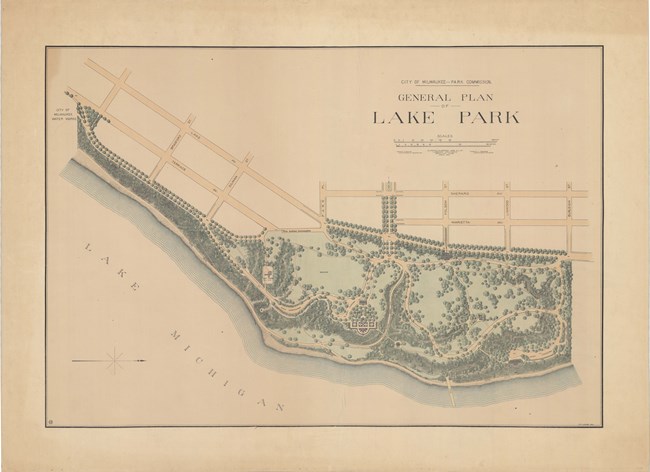

Olmsted Archives Lake Park (Milwaukee, WI)In 1889, Milwaukee began acquiring lakefront land for a new park, asking Frederick Law Olmsted to help with the design. Olmsted agreed, as he was close by in Chicago planning the grounds for the World’s Columbian Exposition. Olmsted believed that greenspaces should be emphasized by the area’s best features, which for Lake Park was a forested, towering lakefront bluff cut deep by ravines.Olmsted organized the park to provide visitors with spectacular views of Lake Michigan, with winding paths going inland and back out to the lake. Olmsted enhanced viewpoints to exaggerate distance and scale, making the park seem much larger than it is. Lake Park’s boundary is thickly planted to shut out the city and by preserving the forest and enhancing streams, Olmsted made the park seem as natural as possible.

Olmsted Archives Volunteer Park (Seattle, WA)To honor veterans of the Spanish-American War, Seattle chose to honor their new park, and the site of the city’s first reservoir, as Volunteer Park. John Charles Olmsted of Olmsted Brothers helped guide development of Volunteer Park in 1903, making recommendations for the placement, style, and potential future of a water tower as an observation deck.John Charles incorporated the reservoir as a prominent visual feature, promoting the construction of an observation deck on the top of the tower, completed and opened in 1908. Except for the water tower, John Charles intended Volunteer Park to be free of all man-made features, allowing the area's beautiful and refreshing landscape to dominate. Today, Volunteer Park is often known as the crown jewel of John Charles’ Seattle Park System, as is the most complete and best-preserved of the Olmsted parks in Seattle.

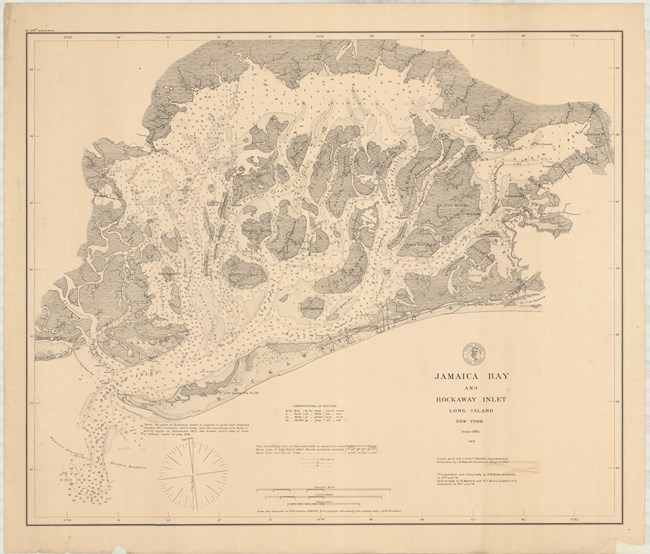

Olmsted Archives Rockaway Beach & Jamaica Bay (New York City, NY)Rockaway Point was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1879 to rival Coney Island and become the new summer resort destination. Olmsted wrote that “there is no place as near and easily & cheaply accessible from New York as Rockaway Point which is also as far removed from conditions of the same class, barring the liabilities which I have pointed out, conditions exist as favorable for recovery and the working off of malarial and diarrhetic trouble.”Preliminary Plans show Olmsted provided a variety of recreation activities like a bath house, pavilion, concert garden, and dancing hall, as well as locations for a hotel and summer cottages. While the area Olmsted proposed now includes several small parks such as Rockaway Park, Breezy Point Tip and Jacob Riis Park, his plans weren’t carried out due to financial problems.

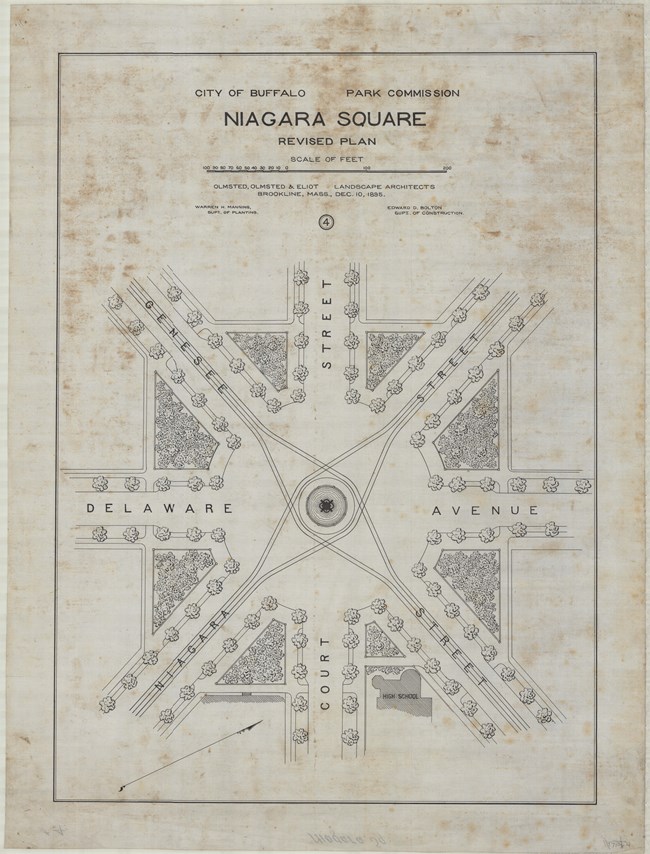

Olmsted Archives Niagara Square (Buffalo, NY)While Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux worked on many aspects of the Buffalo Park System together, after breaking up their partnership in 1872, Olmsted was left to design Niagara Square on his own. Two years after the breakup with Vaux, Olmsted presented a report to the Buffalo Park Commission, rejecting their idea of transforming the square into a public garden. Instead, Olmsted suggested planting trees and providing seating along the square, as well as a fountain at the square’s center.Buffalo’s Board of Park Commissioners hired Henry Hobson Richardson to design an arch at the square, serving as a memorial to soldiers of the Civil War. For the placing, Olmsted requested the arch be “on one side of the Square and so as to span one of the wheel-ways…In this position it would be seen in its best aspect…The best light will then fall upon it; its inscriptions will therefore be more legible and its sculpture will have the best effect.” While Olmsted’s plan was approved, construction never commenced due to lack of funding, and today, the McKinley monument stands at the center of Niagara Square in memory of the President.

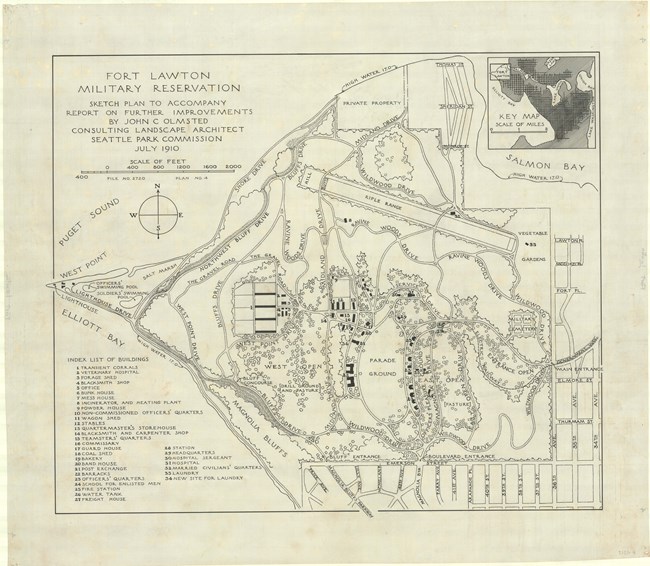

Olmsted Archives Fort Lawton (Seattle, WA)Anchoring Olmsted Brothers’ 1903 plan for Seattle Parks is Fort Lawton, with twenty miles of trails and drives providing access to the area’s water views, beaches, and forests. In 1910, John Charles Olmsted of Olmsted Brothers began preparing a plan for Fort Lawton. John Charles felt obtaining public access to Fort Lawton was important, and he urged Park Commissioners to “secure and preserve for the use of the people as much as possible…of water and mountain views and of woodlands,”.While designing Fort Lawton’s boulevards, parade grounds, and building alignments, John Charles was able to take advantage of the terrain’s dramatic topography and expansive views. Starting in 1968, the military cut back on using Fort Lawton. The City of Seattle was able to acquire the land without cost, promising to turn it into a public park. Now known as Discovery Park, Fort Lawton fulfilled John Charles’ desire as the anchor of the city-wide system.

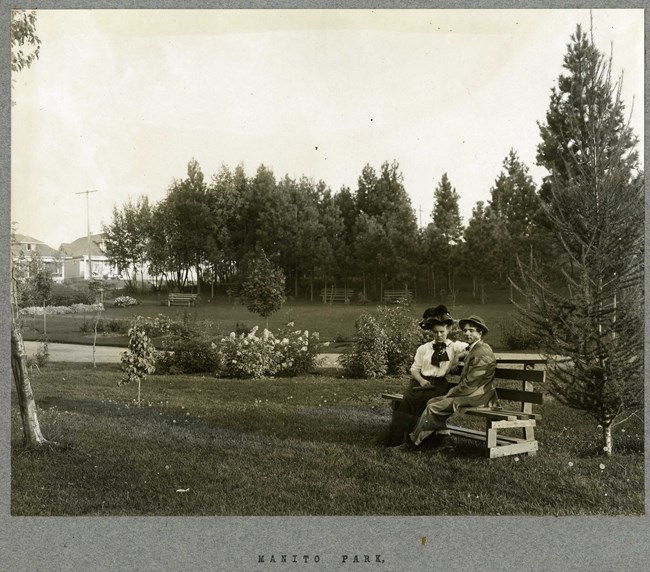

Olmsted Archives Spokane Parks (Spokane, WA)In 1907, Aubrey L. White, President of Spokane’s newly founded Park Board, discovered John Charles Olmsted was making trips to the Pacific Northwest to oversee other projects, and convinced the landscape architect to make the occasional stopover in Spokane. On trips to Spokane, John Charles explored bluffs, river gorges and forests, issuing an ambitious report one year later calling for four large parks, five smaller parks, eleven playfields, numerous parkways, and improvements to the ten already existing parks.White often accompanied John Charles and his associate James Frederick Dawson on outings, going so far as to pay an extra $50 out of his own pocket for as much verbal advice as was possible. In the end, the Spokane Park report from Olmsted Brothers cost the city only $1,000. In the plan, John Charles outlined that every home be within easy walking distance from a neighborhood park, believing "city life ... has a decidedly depressing effect on the general health and stamina".

Olmsted Archives Frink Park (Seattle, WA)In his 1903 report on Seattle’s Parks, John Charles Olmsted proposed the ambitious undertaking of acquiring an entire length of steeply sloped area for park purposes, cautioning locals of the land’s unsuitability for a subdivision development. John Charles believed that “Houses will probably continue to be moved gradually on to adjoining land owned by someone else, and there will be no end to the trouble, expense and inconvenience due to the continuation of the slide if it is allowed to become occupied by houses. . .. On the other hand, the movement of the land would be of small consequence if the ground is turned into a public park.”The land John Charles was working with occupied a wooded ravine with a stream channel winding throughout it. The proposed plan curved along Lake Washington Boulevard, fitting into the slopes as it wound through the park, with John Charles creating a small waterfall as a focal point. Additionally, John Charles placed a network of paths throughout the park, as well as benches and pools. The land was renamed Frink Park to honor the donor who had made the park possible. |

Last updated: June 15, 2024