|

The jagged mountains of Death Valley form a barrier like broken glass atop a wall. They were a warning to the fortune seekers who wished to pass through to the gold fields of California, or lay claim to any of the gold, silver, copper, or borax hidden deep inside the ancient seabed. The mountains also provided a temporary wall of protection to the land’s original inhabitants – the Timbisha Shoshone. Click on the titles below to view each gallery. Please check back periodically, as we are building this collection over time.

Perils of Opportunity- Mines and the MinersIn the last half of the 19th Century, there were those who decided to leave the relatively organized societies of St. Louis, Chicago, or New York to try to find a new life for themselves in California. These travelers were often drawn by the illusory dreams of riches, or sought freedom from stifling traditions. After a difficult journey across the plains and deserts of the Great Basin, some took a southern “shortcut” across Death Valley to avoid the snowy passes of the Sierra Nevada. Here they encountered a parched, unforgiving landscape with summer temperatures which regularly soar to 120 degrees fahrenheit or more. Some, like “Shorty” Harris, Pete Aguereberry, and William Coleman decided to stay and work the rock, eking out a living on gold, silver, copper, and borax. Most moved on as quickly as possible to the verdant valleys beyond the mountains.

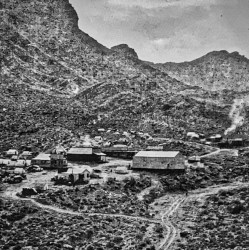

Perils of Opportunity - The Mining TownsThe flow of miners grew around the turn of the 20th Century as word spread of gold that was just lying around on the ground. Nevada boom towns like Tonopah, Goldfield, Rhyolite, and Beatty paved the path southward along what is now U.S. Highway 95. From Rhyolite, old-timers like “Shorty” Harris led new arrivals into Death Valley and its nearby mountains, where they sometimes found deposits of valuable minerals. Millions of dollars of gold, silver, and copper were eventually extracted from some of these mines, but the richest discovery ended up being borax.

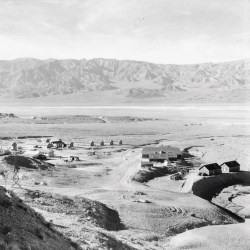

Tourism - The EntrepreneursAs mining opportunities diminished, there were those, particularly the owners of the Pacific Coast Borax Company, who saw the opportunity to transform some of the old mining camps and facilities into hotels and other visitor services. The increase in automobile ownership eased the journey into the valley from the growing population center of Los Angeles. Roads were built along the mining and emigrant trails, and the first tourist accommodations were established to welcome hot and weary travelers.

Tourism - The ShowmenDeath Valley Scotty - it’s remarkable that in such an expansive landscape, one person has so captured the public’s imagination. Even though he died 68 years ago, Scotty’s presence in the stories of the park endures. The mansion in Grapevine Canyon, built and owned by Albert Johnson, is known as Scotty’s Castle.

Tourism - Finding Desert SolitudeDeath Valley National Monument was created in 1933 after years of effort to protect it from mining and other interests. However, it wasn’t until 1994 that Congress designated Death Valley a national park. One of the reasons for the long wait was that the desert had negative connotations for many Americans and was often seen an inhospitable and threatening wilderness wasteland, not a national treasure.

Fighting for JusticeDeath Valley is no stranger to the challenges that have confronted American society over the past 150 years: the Timbisha fought to hold on to their homeland, Depression-era workers struggled for an economic foothold through the Civilian Conservation Corps and Japanese Americans were rushed to Cow Creek from their incarceration at Manzanar during World War II.

Protection and PreservationThere was a time when desert ecosystems were not considered worthy of protection. Deserts were viewed by many as wastelands, devoid of life, valuable only for the wealth that could be extracted from the unending rocky landscape. With no large waterfalls, forests, or mountain majesty, even the National Park System had a hard time seeing the sense in protecting a place like Death Valley. Fortunately, there were those who saw things differently, people like Bob Eichbaum, Stephen Mather, Horace Albright and activist Edna Perkins who saw in the landscape “a mantle of such strange beauty that we felt it was the noblest thing we had ever imagined.” There was also a tiny pupfish that opened a window to preservation, and restoration that unleashed the power of Earth’s resilience.

Power of the EarthDeath Valley is a marvelous exhibit of the forces that shape our planet: it’s clash of tectonic plates that have lifted sea floors to towering heights, the extremes of temperature from the heat of the valley floor to the freezing snow on the mountaintops, and the flash floods that flip cars and tear the earth apart.

Painting Death ValleyPainters and photographers have long been drawn to Death Valley’s rapid changes in light, its vast and stark landscapes, and vibrant, yet nuanced colors. The intensity of the desert environment plays tricks with the soul of the artist - it’s rough, it’s abstract. The lines are remarkably precise before they blur with time. Each of these paintings reflect the humility of the artist in Death Valley’s overwhelming setting. |

Last updated: September 8, 2022